Bob Hurst and Don Bailey are participating in a campaign system that I drew up and sent out via the internet. The objective was to keep me busy for several evenings, fighting the battles either solo, or if some unfortunate individual was to appear in the doorway, with a live opponent.

Five star General Bob "Blaster" Hurst, replete with two ivory handled pistols, commands the US forces in the Pacific. Heís got 7 "armies"... or corps or divisions, or whatever... depending upon the scope of the battle as I set it up on the table.

Blaster Hurstís goal is to invade and take over the 5 islands in the Ooha Island chain, all of which are "presumably" occupied by the Imperial Japanese forces headed by Highly Imperial Warlord General Dono Gimesake, of the highly respectable and ancient Samurai Waka Waka clan.

I use the term "presumably", because, in his initial setup, General Gimesake decided not to defend the island of Nano, and when Blaster Hurstís troops landed on Nano, there, on the beach, instead of being greeting by hordes of fierce-fighting Japanese troops, were thousands of Nanoanians (Nanoites? Nanotonians?), cheering for their liberators, large pennants flying, boom-boxes going full blast, and many potato chip and coke kiosks set out on the beach. Blaster Bob shook hands with the mayor of Nano and sailed off to prepare for the rest of the campaign.

Things went differently on the island of Inyo. As the US forces stormed ashore, there were Gimesakiís men, dug in and ready to die for the Emperor.

There are 7 US armies, and 6 for the Japanese. When I set out a battle, especially in solo fashion, I want no more than 10 or so units per side... enough to provide me with, at most, a 2-or 3-hour game. Limiting the number of units to 10 permits me to track, via the use of data sheets, any pertinent parameters of the involved forces. And so, depending upon the rules, I might record unit strength, or morale level, or some sort of efficiency factor, or ammunition supply. Iíve discovered that limiting the number of records to 10 per side is not overwhelming.

In the initial campaign setup, each side assigned its armies to one of three places.

- a. At HQ. The American HQ was located somewhere at sea, Japanese HQ was located in Japan.

b. On one of the 5 islands. A "stacking limit" of one army per island was allowed... no ganging up on the opposition. While the Japanese were initially permitted to have an army on each island, no US forces were allowed on shore. They had to invade from the sea.

c. At sea, in transit. I purposely provided no maps for the participants. Iíve found out that a "mapless campaigní results in less work for the umpire... me... I have enough work tracking army strengths and locations and unit parameters during a battle. And so the armies, while in transit, could be placed "at sea"... no particular location, simply Ďat sea".

To move between HQ and the islands, or from island to island, a force always had to use one campaign turn by going to sea, thus being in the transit mode.

For the first battle, the landing on Inyo island, Bob and Cleo Liebl arrived to command the opposing forces. Bob was in charge of the US troops, Cleo headed the Japanese, and I acted as umpire.

Most of the battles will consist of amphibious landing scenarios, and in each battle, the defending side informs the umpire, in a general way, as to how he wishes to have his initial forces set up. He can have his entire force hidden in the interior of the island... which will provide lots of ambush opportunities as the invader moves inland... or he can have his troops half hidden and half in the open, permitting him to defend the open beach areas, directly opposing the landing.

Inyo Island

Concerning Inyo Island, Don Bailey told me that he wanted his Japanese troops well hidden inland, and so I peppered the ping pong table with about 20 terrain features... woods and towns... numbered each, and Cleo, as Japanese commander, listed each of her units, together with the number of the terrain item in which the unit was hidden. Her units would be revealed either when they fired, or when an advancing American force stumbled onto their hiding place.

As for the Americans, Blaster Bob had informed me that his invasion force, the 1st Army, was to be reinforced with his 1st Airborne Reserve, and that he had allocated one aircraft strike to the landing. I informed Bob Liebl of this.

The Japanese, too, possess several airborne reserve units, and a couple of airstrikes, but none for the Inyo Island encounter.

About a week before, I had tried the rules out on Jeff Wiltrout, and he gave them a fairly low grade. Inyo Island, therefore, was to be the second outing of the rules, and I had revamped them, trying to paper over the cracks and holes discovered during the first scenario.

The basic maneuver element was termed a brigade. I used my 15mm WW2 troops, and defined 4 stands, either 4 infantry or 4 tanks, as a brigade. The US landed with 12 brigades, a mix of armor and infantry, while the Japanese defended with 9 brigades.

Techniques

I had recently read quite a bit about techniques used in boardgames, and I hoped to incorporate some of the ideas into the miniatures game. Two items in particular, were:

- a. Force step reduction. In a boardgame, a unit started out with a certain strength stated on the topside of its cardboard token. When it was hit, the token was turned over and a lesser strength revealed. A second hit and the token was eliminated.

The "step reduction" technique that I employed had one of the combat results in a battle as one or more of the tokens in a force (one or more of the 4 brigade stands) destroyed outright, or placed in a repair zone and brought back to the unit later in the sequence.

b. A second boardgame technique was "unit dispersal". A force would attack with a huge stack of tokens all conglomerated within a single hex, and one of the possible battle results was that the component tokens would be dispersed... the stack would be broken up, some going this way, some going that way.

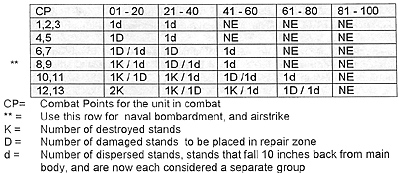

And so, in my combat chart, a possible combat result was that one or more of the stands in a brigade would "disperse"... they would fall back, 10 inches, from the brigade, and have to rejoin the unit later on. Below is the combat chart I drew up. Ordinarily, I despise the use of charts, I insult those who employ them, I mock the authors who present them, I ridicule the gamers who advocate them, and I laugh at the silly chartists who regard them as the last word in historical reality, accuracy and authenticity.

But here I am, tasting bile as Iím forced to present my own silly chart. What has the world come to?

The key reason for use of a chart is that there are three possible results of combat... a "kill", a "disperse", or an "off to the repair zone", with a mixture of each. I couldnít see any way to use a simple formula to obtain all the effects needed. To use the chart for each fire or combat phase, sum up the Combat Points (CP) of the unit involved (giving the row number), and toss percentage dice (giving the column number).

The little "d", or dispersal, effect was fairly important. For example, here are the CP values of a group of infantry stands

- 1 stand 1 CP

2 stands 3 CP

3 stands 5 CP

4 stands (full brigade) 7 CP

Notice that thereís a synergistic effect achieved by conglomerating lots of stands. A single infantry stand is valued at 1 point, whereas 2 stands total, not 2, but 3 points, and 3 stands total 5 points. Armored units follow the same pattern:

- 1 stand 2 CP

2 stands 5 CP

3 stands 7 CP

4 stands (full brigade) 10 CP

The above values indicate that as a brigade is force to disperse, its combat value suffers quite a bit. Strength does not go down linearly. And a second result of the little "d", is that the sequence forces the sides to use up precious movement actions to reassemble their brigades.

When a side is active, it dices for movement, and receives a number of actions which can be assigned to various groups. A dispersed, single stand is a group, hence the more a unit is dispersed, the more the actions that must be devoted to reorganizing it.

On Inyo Island, in accordance with the Japanese commanderís wishes, the defending forces were located inland, and the US forces, landing on the beach, were initially unopposed.

Initial Turn

On the initial turn, Bob Liebl called on his airborne reserves. Some weeks before, Don Bailey had provided me with a half dozen little paper glider models, and Bob took two of these. He stood back, some 4 feet from the table, and launched his gliders. Wherever the paper models landed, that was the point at which the airborne troops debarked. We gave Bob a couple of practice launches, and when he was deemed sufficiently well versed in glider landing procedures, in came the airborne!

One of the airborne units was a full, 4-stand infantry brigade, and the other was a 3 stand infantry unit. As I remember, the airborne didnít get as far inland as Bob wanted... they landed near the beach.

Another procedure Bob called upon just prior to landing his troops, was for an offshore bombardment. He diced for either 4 or 3 or 2 barrages, and came up with 3 of them. He then pointed to a terrain feature, and went to the above combat chart.

Note that thereís a specific row devoted to naval bombardment. Each blast has a 60 percent chance of inflicting damage. Bob pointed at 3 terrain features, beach-side, and we marked the results on a chittie ("K" or "D" or "d") and when Cleoís Japanese unit was revealed, we adjusted it accordingly. Since Cleoís defending force was located inland, the beach bombardment did Bob very little good.

When the active side diced for unit actions, initially, the table looked like

| DICE THROW | ACTIONS |

|---|---|

| 01 to 33 | 6 |

| 34 to 66 | 5 |

| 67 to 100 | 4 |

An action permitted a unit to move 5 inches. A unit could be assigned anywhere from 1 to all the requisite actions, but this, of course, penalized other units which were thus deprived of their own movement actions. Note that for a 10-unit force, the maximum number of units that could move at any given time was 6.

And note that in describing the table, I used the word "initially"... after playing several bounds, it was determined that there werenít enough actions around to keep all the forces moving. Each side had around 10 units or groups at the outset, but each firing and close assault phase produced more dispersed units, i.e., more separate groups running around on the field, and it became more and more difficult, when a side became active, to keep the flow of the game moving properly.

And so we "upped" the above action chart... instead of 6,5,4 actions, we changed it to 8,7,6. But, in truth, even this wasnít truly sufficient.

There were 8 towns on the field, and when the American forces had overrun and captured 5 of them, I deemed it a sufficient victory condition to declare the battle won for the red, white and blue.

Back to PW Review May 2001 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com