Bob and Cleo Liebl hosted what they termed a campaign game in 15mm for Napoleonics. They anticipate six participants, and I participated in the test run, in which there were only three... it still ran quite smoothly.

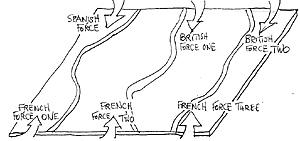

The table-top map uses Bob’s good-looking 2-by-2 terrain boards, laid out to present a baseline of 10 feet for either side and a table depth of 4 feet. A simplified version of the map is shown below. In essence, each side has three field forces, each composed of one or more divisions. And so, what results is, in fact, three separate, simultaneous, parallel battles.

The objective of each field force is to maintain control of the roads in its sector which lead off the field. Not all the forces are equal, and it is permissible for a commander to divert a unit or two, and send a fellow commander an assist. Cleo did just that during the battle. My force was on her left, and her own force outnumbered the enemy facing hers. She thus felt she could spare a couple of units, and so two of her infantry brigades, accompanied by a battery, raced to assist my troops.

Now that I’ve related all the good, common-sensical stuff, let’s get into the nitty gritty. First of all, as Bob was describing the game, he started handing out... omigawd!... data sheets and charts of NAPOLEON’S BATTLES (NB)!!

Now that I’ve related all the good, common-sensical stuff, let’s get into the nitty gritty. First of all, as Bob was describing the game, he started handing out... omigawd!... data sheets and charts of NAPOLEON’S BATTLES (NB)!!

What proved of interest to me was that, continuously throughout the game, Bob kept saying: "I know the rules aren’t perfect, but...!" After much cogitation, I think I figured out why he exercised NB.

Bob placed the scenario in 1813, and his desire was to outfit the units that existed in that year with their proper historical functions. And so he went to the silly-pseudo-historical NB charts, which go into great detail concerning the capabilities of units during different periods within the Napoleonic era. In 1813, for example, NB informed me that my French line troops could march forward, when in column formation, a distance of 9 inches per turn.

One year before, however, they could have zipped along, when in column, a distance of 10 inches. Below are a couple of chart excerpts for French line infantry; I’ve listed only three parameters for four different time periods, but there are 14 parameters for every unit, for every nationality, for every time period. It makes Scotty Bowden green with envy.

| Period | Movement in column, inches | Movement in line, inches | Combat modifier for line formation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1805-1807 | 12 | 3 | +3 |

| 1808-1812 | 10 | 3 | +2 |

| 1813-1814 | 9 | 1 | +1 |

| 1815 | 10 | 3 | +2 |

And so Bob Liebl, being a historical gamer at heart, in placing his game in the year 1813, took the NB charts at face value, trusting in the wonderful and detailed research performed by the NB authors, and accepted the listed numbers.

And, when you think about it... why not? After all, a number is a number, and if NB said that French troops could advance 10 inches in column in 1812, but only 9 inches in 1813, then why not? If you believe all the listed crappola, you get a warm, fuzzy, historical feeling in your heart, and you know you’ve done The Right Thing.

But what the above leads to is a lot of chart looking-up. On the field were British troops and Portuguese troops and Spanish troops and Bavarian troops and Italian troops, and I’m not sure what else. And the charts for each one of these, infantry and cavalry, had to be referenced to find out their movement distances and their melee values and their ‘emergency response’ numbers (to form square when cavalry attacked) and their ‘rout numbers’ (the number of casualties taken in one half-turn to rout) and so on.

For a while, I tried to keep up with Bob as he went through chart after chart for us, but I soon gave up, and Bob became the sole great adjudicator and prime reference for the firing and melee phases.

My own force, a small French corps in the middle of the field, consisted of 2 divisions. One of them was led by General Maransin, who had a 3-inch command radius, and a ‘control number’ of 6. When Maransin tossed a 10-sided die and the result was 6 or less, all of his units, located within 3 inches of him, could move as ordered.

How about the units more than 3-inches away? Tough on them, buddy! They stood... simply stood... they couldn’t change formation, change facing, move... but at least they had the smarts to fire if an enemy came frontally at them, within musket range (4 inches). The only way to get them going again, was for Maransin to ride up, kiss them on their collective cheeks, toss his control die and hope for the best.

The control functions within NB which govern unit movement are fairly strict, fairly limiting. Keep your units bunched up, close to their commanding officer, and most of the time, they’ll do as you say.

NB follows many rules sets which use the mystical-and-magical-aura routine for command and control. The commander gives a unit his orders, and rides off a wee bit beyond his ‘control radius’... and what happens? Nothing! That’s what! The men in the unit immediately go into deep sleep, into their cryogenic chambers, and stand by until the commander returns to give them a booster start again.

For me, however, the icing on the cake concerned the NB procedures followed when determining the result of a melee. Here, both sides toss a 10-sided die in melee, and the difference is the number of casualties suffered by the losing side. And if the casualties exceed a given number, determined by the chart value for that particular 1813 unit, the unit will immediately rout.

And to where will it rout? I asked this of Bob several times, since my dice weren’t too high in the melees, and I had a lot of routing units. And Bob would look at the field and he’d say... "I suggest that you have the unit rout over to the woods where the commander is located, so that, on the next turn, he can rally it!" Or he’d say... "You should have the unit rout behind the woods to shelter it from the enemy."

In other words, I had complete control as to where I could have my routing unit run! Here were these terrorized, helpless men, fleeing for their lives, trying to save themselves, and I could have them move exactly as I desired!

What happened to all the command-and-control crap? When the units were in good order, in good shape, then, half the time, due to the control die roll, they wouldn’t listen to me or their commander, and just sat, while here, when all control was supposedly gone, and the unit had lost all coherency, I could herd it as I wanted.

Yes, NB is a great set of rules!

Believe it or not, guys, I really hate to find fault with a given set-up, but I must mention that Bob’s scenario, even without NB, quickly turned into a Class AAA Abomination. Bob’s units were not labeled, and so, when they took hits, we couldn’t keep data sheets on them.

But what we could do was to place those wonderful, wonderful casualty caps over the heads of the men in combat. An infantry unit had some 4 men per stand, and when it took its fourth hit, i.e., received its fourth casualty cap, a stand was removed.

But that wasn’t all! There were all sorts of headgear being placed on the units.

- Black casualty caps indicated the hits on the unit.

A blue casualty cap indicated a unit was disordered.

A red casualty cap said the unit was routing.

A yellow casualty cap on a cavalry unit said the unit was ready to perform an ‘opportunity charge’ at the enemy.

At battle’s end, my only suggestion concerned the casualty rate. A 6-stand British unit had 24 men in it, and around half of them had to die, some 12 hits, before the unit ran off. I suggested that a single hit - or perhaps 2 hits - remove a stand. This would speed up the game, and bring an end to the NB procedures that much more rapidly.

Back to PW Review February 2001 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com