Jeff Wiltrout visited while I was in the middle of this solo effort. “What’s going on?”

“The Japanese are defending against an advancing larger British force”, I explained.

“Then tell me on which battle front, when the British fought the Japanese, there were pine trees on the field!”

Oh! Oh! Jeff had caught me with my pine trees down. I had set up the field… a couple of towns and a lot of small wooded copses… without regard for the historical veracity of the foliage. In doing so, I had set out a number of wooded areas, pine trees galore, each around 5-inches by 5-inches, which I had recently crafted specifically for my 20mm WW2 Lannigan Brigade figures.

The stands for the troops measured 2-inches by 1˝-inches, and I wanted one stand to fit within a single 5-inch by 5-inch wooded area. Over the years, I had looked at the shelter provided by woods in two different ways.

First, was the old fashioned way, in which wooded areas were rather large, and when a unit, or several units, entered the woods, they could dive deep into the area and claim they were out of sight of all external observers. And being out of sight, they were also unable to fire out. Later on, if they wished, the units could then move up to the edge of the woods, and declare they could see and be seen, and thus also be able to fire out and be targeted by the enemy.

The second manner of regarding woods was the CROSSFIRE way. CROSSFIRE is a WW2 game in which the maneuvering element is the single stand representing a squad. The author’s (Artie Conliffe) thoughts on wooded areas were that, in his scenarios, woods were small enough and penetrable enough that, for gaming purposes, a unit couldn’t really “hide” in the woods.

It could see out and be seen, and could fire and be fired at, and the woods would provide a negative covering modifier when it was targeted.

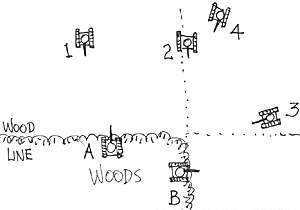

Look at the figure I’ve sketched. There are two tanks, A and B, perched on the edge of a wooded area. They can fire out and can be seen... but the question is... by who? I’ve extended the woods line to show the positions of four enemy tanks.

Look at the figure I’ve sketched. There are two tanks, A and B, perched on the edge of a wooded area. They can fire out and can be seen... but the question is... by who? I’ve extended the woods line to show the positions of four enemy tanks.

- Tank 1 can certainly see A but not B… no problem here.

Tank 2 can see A, but can it see B?

Tank 3 can see B, but can it see A?

Tank 4 can see A, but can it see B?

These question arise when the “old fashioned” method is used. During a visit to Bob Hurst’s house, we bunked heads on this all the time… essentially, the discussion centered on the question of what should be the “angle of reflection” when peering along the edge of the woods so that a tank, such as Tank 3 in the sketch, could see Tank A. We came to no great conclusions.

Which is why I like the CROSS FIRE method. Everyone sees in, and everyone sees out. Which is why I created my 1-unit-per-wooded-area sections.

The Battle

But now, let’s concentrate on the battle. I defined a single stand as a platoon, and 3 stands became a company. The British had one heavy tank company, one light tank company, and one APC company. Each APC carried a platoon (one stand) of infantry, and when the infantry debouched, or debarked, or jumped out, or whatever, the APCs could provide supporting fire, in effect, providing the Brits with another unit. The British force also had 4 additional foot slogging infantry companies.

The defending Japanese had a heavy tank company, a somewhat abbreviated armored car company (it only had 2 platoons instead of 3), and 3 infantry companies… the Imperial Japanese force was outnumbered, but undaunted.

For years, whenever a token fired, my modern rules used a single dice roll to see if the target was hit, and if so, how many “effectiveness points” it would lose. I always assumed that, if hit, the target would always lose a couple of points, no matter the relative size between the gun firing and the target armor.

I had recently been looking at a number of WW2 rules, all of which used two separate dice throws for the firing routines. First, you’d toss dice to see if the target was hit, and second, more dice to see if the target’s armor was penetrated. Well, said I, if real wargames rules used two sets of dice throws, than so would my set… I refuse to be known as a whimp on the aspect of historikal realistikness.

And so this new, brand-new, all-new set of rules incorporated a chart of to-hit probabilities. And it also broke new ground in another area… I added a rate of fire for the weapons. Which means that not only do you get to toss dice to see if you hit the target, and toss ‘em again to see if you penetrate the target, but if the rate of fire is more than one, you get to do it all over again to see how may times you hit the target.

Take that, SPEARHEAD! Take that, COMMAND DECISION!

The British forces led off by advancing with their company of 3 APCs, each vehicle bearing a one stand platoon of infantry. The active side tosses a number of 10-sided dice for each company… if the number of platoons within a company is N, the number of dice is equal to N+1.

And so I tossed 4 dice for the 3-platoon APC company. What the dice told me was as follows:

- Toss of 1,2,3,4,5 Assigning one of these dice to a platoon permitted

it to advance 10 inches.

Toss of 6,7,8,9,10 Assigning one of these dice permitted a platoon to fire. But there was a restriction here… only one of these fire dice could be assigned to the company, i.e., only one platoon was permitted to fire on this phase.

The 4-dice toss of the APCs came out to be 2,6,8,8

I assigned the 2 to APC#8 and it advanced 10 inches. The other two APCs remained on the baseline. I could have assigned APC#8 one of the higher dice to fire, but at this stage there were no visible targets.

I kept tossing dice for the other British companies, and most of the British platoons advance… only a few hung back.

After the active side was finished, it became the non-active side’s turn to fire. And here I tossed N+1 dice again for each company. The results of each die were a little different from the those of the first phase.

- Toss of 1,2,3,4,5 A platoon assigned one of these dice could not fire.

Toss of 6,7,8,9,10 A platoon assigned one of these dice was permitted to fire.

This dice distribution during the fire phase meant that, sometimes, not all the units on the non-active side’s roster could fire. It turned out that one of the Japanese armored cars fired on APC#8, and, here, we have to examine the Fire Chart for heavy weapons fire.

| WEAPON | ROF | POH | Armor | Penetration | Effective Range* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAW | 2 | 70 | NA | 60 | 30 |

| A/T | 3 | 60 | NA | 50 | 30 |

| Hvy tank | 2 | 60 | 30 | 40 | 20 |

| Bazooka | 2 | 40 | NA | 50 | 0 |

| APC | 3 | 40 | 15 | 20 | 10 |

| Light tank | 3 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Armored car | 4 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Note that the rate of fire (ROF) for the armored car is 4. Why? Because I sez so, that’s why! And so I tossed percentage dice 4 times for the armored car… the chart gives its probability of hit (POH) as 40 percent. Why? Because I sez so, that’s why!

No one is ever supposed to argue with listed or charted values. They are given a supreme, innate aura of authenticity and legitimacy and cannot ever be questioned. Here, my listed values were the results of days, nay, weeks of intensive study. Of the four 40 percent tosses at APC#8, two were successful… the vehicle had been hit twice.

Now we look at the remainder of the chart. We see the armored car has a Penetration factor of 10 and the APC has an Armor Value of 15. Why? Because I sez so, that’s why!

We want to reduce the Penetration factor by the target’s Armor Value. In this case, the target has a higher Armor Value than the firing weapon, and we get a delta of 10-15, or -5.

Now we toss percentage dice again, and subtract the delta factor. In fact, we toss the dice twice, once for each registered hit, each time subtracting the delta. The results here were:

- First toss was 63. Subtract delta gives net of 58

Second toss was 52. subtract delta gives net of 47.

Now we take the tens digit of the net values, here, one was 5, one was 4, a total of 9, and so I crossed 9 points off the target’s record sheet. Each platoon had a data sheet which looked like:

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

When 20 points were crossed off, the unit was destroyed. In this case, APC#8, as a result of this first volley, had only 11 points left. If it was destroyed without the troops inside disembarking, they’d be lost, too. And so, on the next British active phase, I made sure that the platoon riding on APC#8 dismounted.

Note that if a heavy tank fired on an APC, the delta would have been the Penetration factor of 40, less the Armor Value of 15, or a +25, and we’d add the +25 to the percentage dice throw to get the number of loss points crossed out.

Back to Battle

On the eastern side of the field, my right side, the British and the Japanese had gathered their heavy tanks, with the British backing up their heavy stuff with their light tanks. This made for 6 British armored vehicles versus 3 Japanese vehicles, and a huge, huge, absolutely awesome, Kursk-type tank battle took place! Think of it! Six tanks versus three! Never before seen on the Simon ping-pong table! The result was that both sides lost all their heavy tanks, while the British managed to save 2 of their light tanks.

In the middle of the field, after the British infantry dismounted from their APCs, the APCs made short work of the under-staffed 2-platoon Japanese armored cars.

Note, by the way, that the Fire Chart has a provision for the firing of a LAW weapon. Not too many people know that this secret anti-armor weapon existed during the Second World War… readers of the REVIEW are now part of the privileged few that possess this knowledge.

I gave each infantry platoon two LAWs to carry… and they were deadly. Note that they had an ROF of 2 (I tossed percentage dice twice every time they fired) coupled with a high POH of 70 percent. Most of the tank damage occurred when the infantry let loose their LAWs. In fact, you might say I overdid the LAW business… but you’ll never get me to admit it.

At battle’s end, only one Japanese infantry company remained, plus one heavy tank. A decisive British victory.

Back to PW Review December 2001 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com