Bob Liebl and Mike Byrne teamed up as the French commanders in this British-versus-French battle. Their forces would enter on their baseline. I, as a slightly outnumbered British commander, indicated, on a map of the table-top, where each of my units was located. As the French approached, my boys would pop up and get first fire.

Prior to the game, Bob glanced at the 3 pages of rules I had drawn up… one glance was sufficient… “May I make a suggestion?” he said.

When Bob says “May I make a suggestion?”, this is tantamount to his saying “This is one of the silliest sets of rules I have ever seen, and my suggestion can only improve upon your procedures and make them more historic.”

Bob’s eyes had fallen on the section devoted to firing, and he noted that musket range was listed as 15 inches. He indicated that a ‘more proper’ range for the muskets should be in the order of 5 inches. But I was ready for him… “Horse puckey!” I replied, “A better range, more in keeping with the scale, would be about an inch!”

And so, even before we started moving our units, we engaged in a stimulating discussion on the range and effect of musket balls in the Napoleonic era. I had defined a single stand of my 15mm Napoleonic figures as a battalion. A 600-man Napoleonic battalion in three ranks had a frontage of some 150 yards, hence the battalion frontage could be used as a first order approximation of musket range on the table-top. Here, the 1-inch frontage of my infantry stands should have indicated a 1-inch effective range.

Why 15?

Then why did the rules state that musket range was 15 inches? This, in effect, gave the infantry an over-the-horizon capability of firing. Not to worry, I replied. This is common practice in the Simon rec room, and it’s done for two reasons. First, it ‘opens up’ the game. It gives units a wee bit of flexibility and maneuverability in firing, and they don’t have to move up and be nose-to-nose with the enemy before the troops can pull their triggers.

Second, I’ve always maintained that, in a battle environment, the impact on a unit, when fired upon, should extend well beyond the actual effective range of the musket balls. When the targeted unit sees the enemy let off a volley, and the firing table indicates the target takes a hit, the hit is translated to mean that there’s a diminution on target strength… the Simon theory is that this decrease in strength can result not only from the leaden balls actually smacking into someone, but also as the result of several fellas in the target unit deciding that the front line of battle is not the place for them, and taking off. Hence, regardless of the cause, the effect is the same… a hit is registered even though the firing unit’s musket balls are “out of reach”.

Bob was not at all happy with my theory. He was also unhappy with my canister range… listed as 10 inches. Canister effect should extend beyond musket range, was his argument, especially in this smooth bore era. In truth, I agreed, but I certainly didn’t tell him that. Firing canister has a more horrific effect than that of the regular musket volley, but I dislike making it all-powerful. With the extended ranges in my rules, I didn’t want artillery fire to take over the game, so I limited the range of canister to be less than that of musketry.

Which brings up the question of just how much more of an impact a canister shot will produce on a target than a musket volley.

I didn’t want to simply state “… add +20 to the dice throw when firing canister”. Instead, I gave the battery firing canister two bites at the apple… it went to the Fire Effect Table, shown below, twice, i.e., tossed its percentage dice twice. There are six possible types of impact listed in the table, and they’re all oriented toward reduction of a unit’s Capability Level (CL).

-

DICE

EFFECT

01 - 25 Target brigade loses 1 CL if in the open, no loss if in cover

26 - 45 Target brigade loses 2 CLs if in the open, 1 CL if in cover

46 - 55 Target brigade loses 3 CLs if in open, 2 CLs if in cover, regiment takes immediate morale check with -5 modifier

56 - 80 Target brigade loses 1 CL, regiment takes immediate morale check

81 - 90 Target brigade loses 2 CLs, regiment takes immediate morale check with modifier of -10

91 - 100 Target brigade loses 1 CL, regiment or battery immediately returns fire by dicing on Fire Effect Table

Prior to the game, the sides diced to determine unit CLs, which ranged from 60 to a low of 50. The CLs were the end-all and the be-all of the gaming structure. When a CL was reduced to zero… the unit simply vanished… it had had enough.

Note in the table that the reference is to a CL loss in a “brigade”, not to a regiment or battalion. The organizational setup, in defining a single stand as a battalion, placed 3 to 5 battalion-stands in a regiment, and 3 regiments in a brigade. The regiments were the maneuver elements. Thus each brigade was made up of three separate regimental units, and when the enemy directed fire against one of the component regiments, it was the brigade itself which recorded the losses, and reduced its CL.

All three of the regiments within a brigade had the same morale level, defined as the sum of a standard base of 30, plus the brigade’s current CL. Which meant that as the brigade’s CL went down , so did the morale level of all of its regiments.

The French had 7 brigades, the British had 5. The paper work, in recording CL values as the brigades went into action, one number per brigade, was quite easily performed. And I had added a second recording requirement. The need for this comes about because if, after engaging in combat for a couple of bounds, a brigade’s CL was down to, say, 32, its morale level was the base of 30 plus 32, or 62… not an encouraging number at all.

And so I gave each Brigadier a number of Reserve (R) points with which he could assist his regiments by adding to their morale levels. R points ranged from 40 to 50, and were never renewed.

The R points could be used in several ways as the Brigadier helped his units in combat. First, as I indicated, he could allocate points to assist a single regiment in passing a morale test. These morale tests occurred during the firing and melee phases… note in the above Fire Effect Table that several of the results require that the targeted regiment take a morale test, and so individual regiments could be assigned R points.

Second, he could allocate his R points to add to the CL of the brigade as a whole. During the bound, one of the phases during the sequence permitted the Brigadier to augment the current CL of his brigade, thereby helping out all of his regiments.

And a third type of assistance provided by the Brigadier was in the combat phase, when the R points could be called upon to assist in melee.

The result of all the above was that for each brigade, two numbers had to be tracked… the CL and the Brigadier’s R points. Not at all difficult when there were only 7 brigades for the French, and 5 for the British.

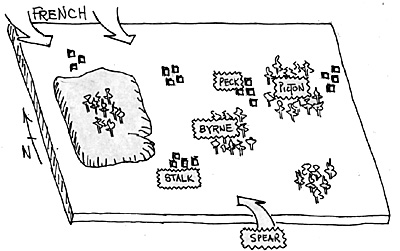

On the map, I’ve indicated where I placed my 5 British brigades. The names of the Brigadiers are noted within the squiggly-line boxes. On the field were four infantry brigades, and off the board, to the south, was my cavalry brigade, headed by Brigadier General Spear. The French were all initially off-board, and could come in anywhere along their northern baseline. There are 5 towns on the field, each worth a certain number of victory points… even I didn’t know their values.

With 4 infantry brigades, I couldn’t defend everything, and so I spread my forces as shown, from east to west.

Strategy Session

Prior to the first phase, the French commanders held a strategy session. I left the room, heard them muttering in pseudo-French accents, re-entered the room and discovered that… French trickery… they had decided that the entire French force would congregate in the northwest quadrant of the field, as shown by the arrows.

They had lucked out, and since I hadn’t defended that quadrant, the two towns in that region (and their victory points) quickly fell into their hands. As they advanced, the first of my British units to open fire and reveal itself was Byrne’s brigade… his artillery, with a 30 inch range, tossed dice on the Fire Effect Table shown above. The targeted unit was a French artillery battery (one stand), already set up and about to fire.

The toss for Byrne’s guns was a high one, in the 90’s. The table says that the target brigade loses 1 CL factor, and immediately returns fire. The dice throw for the return fire at Byrne’s battery was 82, which says that the targeted brigade loses 2 CLs, and the targeted unit, i.e., Byrne’s guns, must take a morale test with a modifier of -10 points.

When I had diced for Brigadier Byrne’s CL points, he had come out with an initial total of 60, the maximum possible. Now he reduced his CL by 2 down to 58, and took the morale test.

He added the standard base of 30 to his CL of 58, deducted the modifier of -10 as required by the table, and his morale level was 78… a fairly respectable number. So respectable, in fact, that I decided not to have Byrne assist the artillery crewmen by tossing in some of his R points.

And the result was a 93! The battery had failed its test… it took off, limbered up and ran back 10 inches, and, due to the morale failure, Byrne deducted another 2 CL from his total… after this first exchange of fire, his brigade was now down to 56 CL.

In the initial long range artillery duels between the sides, the British… my boys… were extremely unlucky. Several of my batteries were targeted and hit, their brigades lost CLs, and in a fashion similar to that started by Byrne’s guns, whenever they had to take a morale test, they failed and fell back.

As the French advanced south, and came within range, this deprived me of my canister blasts, in which, as I previously explained, the battery gets to toss dice twice on the table. Movement was fairly rapid, and the French came up rather quickly.

In the sequence, when it was the active side’s turn to move, it drew an action card with either 2, 3, or 4 actions. Each action entitled all units to advance 5 inches per action… and so, with a lucky draw of a 4, all units could zip up the field a distance of 20 inches. The fire phase was independent of the movement phase, and the number of movement actions didn’t affect firing.

Bob Liebl, in another display of French trickery, took the 2 brigades of French cavalry and ran them south along the western edge of the map, trying to outflank Brigadier Stalk’s brigade. Stalk had all his regiments form square to counter the cavalry, but this made them vulnerable to infantry attacks. What was really needed was the British cavalry, which finally appeared on the 3rd Bound. And even then, the single British cavalry brigade was outnumbered by the 2 French brigades.

When two regiments met in melee, we referred to a Combat Effect Table, similar to the Fire Effect Table, except that the results were more horrendous. While the fire table looked at losses of 1 or 2 CLs, the combat table inflicted losses of 4 or 5 CLs.

My British cavalry, commanded by Brigadier Spear, charged into the French horsemen… and lost. Each unit referred to the combat table a number of times. For example, when my first charge resulted in a loss for one of my cavalry regiments, the French followed up and caught my retreating unit in column formation.

Here, the charging French unit got to toss several times on the chart… one time just for existing, one time for having a supporting unit within 10 inches, and a third time for catching my regiment in column… a total of 3 tosses. Against this, my British unit got to toss on the table only once… for existing.

Each toss resulted in a loss of, perhaps, 4 or 5 CLs, and three tosses thus poked quite a hole in Spear’s cavalry brigade’s CL. Since both of the regiments in the cavalry brigade were each attacked, and each lost twice, the total CLs in Spear’s Brigade bottomed out… even tossing in Spear’s reserve of R points didn’t seem to help.

Once the British cavalry were finished, Stalk’s brigade was easy pickin’s.

I had placed Picton’s Brigade over on the eastern side of the field, and he moved out westward and met with, and was held up by, an advancing French unit. Picton was effectively cut off from the western side of the board. Picton somehow managed to do nothing right when he encountered the French. French fire caused him innumerable CL losses and morale tests… and he failed them all… causing even more CL losses.

And then it was Brigadier Peck’s turn. He, too, headed east, and he, too, met with resistance.

The bulk of the French force, 4 brigades strong… plus cavalry… smashed into the brigades of Stalk and Byrne. A very uneven match.

Not even the dreaded “reaction point” ploy helped the British. As an example of the use of reaction points, one of Stalk’s infantry regiments, having failed a morale test and retreated in column formation, was caught by a French cavalry unit. Trying to protect the infantry, I took one Reaction Point (RP), and ordered the infantry to form square in the face of the cavalry charge.

Having allocated the RP, indicating the order was sent, I now diced to see if the order had arrived successfully… a toss below 80 indicated it had. And so the infantry regiment formed square, ready to stand off the cavalry. But now, the cavalry could also react… Bob Liebl assigned one of his own RP, and sent the French cavalry an order to pull back (80 percent chance of success). His dice toss was successful, and so the cavalry aborted its charge.

Reaction Points, CL factors, R points… none of them did the British any good. The French simply overran the field… no contest… and many victory points.

Back to PW Review August 2001 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com