First, let me note that FIRE & FURY (FF) is not my favorite set of rules. I think the sequence is not appropriate for the horse-and-musket era, I think the fire chart is ridiculous, I think the melee results chart is silly, and so on. The rules are very popular, indicating that many people think they’re playable, but this doesn’t make them a ‘good’ set of rules.

First, let me note that FIRE & FURY (FF) is not my favorite set of rules. I think the sequence is not appropriate for the horse-and-musket era, I think the fire chart is ridiculous, I think the melee results chart is silly, and so on. The rules are very popular, indicating that many people think they’re playable, but this doesn’t make them a ‘good’ set of rules.

And I noted in a recent issue of Hal Thinglum’s MWAN (Nov/Dec 2000, Number 108), Bill Grey set forth 20 pages of pap on a Napoleonic variant of FF, while essentially using the same inappropriate sequence, the same ridiculous fire chart, and the same silly melee results chart.

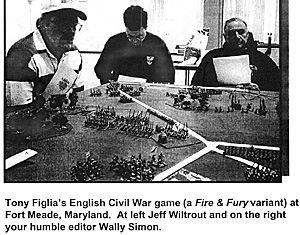

Therefore, when I got an e-mail from Tony Figlia, stating that he had an ECW version of FF, so excited was I that I immediately volunteered to fight for Parliament in Tony’s test battle.

There were 10 participants in the game, 5 for the King, 5 for Cromwell, and Tony had set out his goodlooking 15mm army on a table that measured some 5 feet across and 8 feet long. All units were pre-positioned on the table, so we didn’t have to waste time taking figures out of the box, and engaging in a ‘strategy session’ (“You set your division on the right flank and move to the left to support Vladimir, while he’ll attack the village”). Everything quite efficiently laid out.

My division wasn’t really a division… it was termed “Lt. General Ballies’ Brigade”. It contained three cannons (2 light and one medium), one heavy cavalry lancer squadron, 2 units of dragoons (which I used throughout the game as skirmishers on foot), and 2 pike-and-musket units… a total of 32 stands. There were 5 commands in our force, hence we had a total of around 150 stands on our side. And the same for the King.

I’ll denote this FF variant as Tony’s FF, or TFF, to distinguish the two rules sets. There are 3 status levels in FF for the units in the field… fresh, worn and spent... which depend upon unit losses. TFF followed this. For example, my lancer cavalry, with 4 stands, was fresh with its initial 4, worn when it lost a stand, and spent when it was down to 2 stands. Similarly, my large musket-and-pike unit of 4 musket stands and 4 pike stands, was fresh initially, worn when it lost 2 stands, and spent when it lost 4 stands. The ‘fresh’, ‘worn’ and ‘spent’ designations come into play when you move a unit, and when it’s engaged in combat.

As with FF, TFF started with the active side dicing to activate each unit to see if it would move and obey orders... each unit... I repeat… each unit. That means that I had to toss dice 8 times to activate my 8-unit brigade. The results can range from ‘obey orders’ to ‘retreat full move’ to ‘unit removed from play’. To me, this is time consuming and unnecessary… if you want to restrict a commander’s movement prerogatives, one single dice toss, combined with a couple of modifiers, can easily be used to tell him how many of his troops will obey.

I sent my skirmishers out ahead… they were well spaced… each stand was about an inch from the next, and the 7-stand line extended out to some 12 inches. On the King’s movement phase, Royalist cavalry charged the skirmishers and contacted one of the end stands. This was followed immediately by my, that is, Cromwell’s, defensive fire. In firing, my men placed a disorder marker on the cavalry.

Then it was the Royalist turn to fire. Here, I came across something with which I vehemently disagreed. Despite the fact that the cavalry had contacted only the end stand of my 7-stand unit, and the other 6 stands were way, way out, clearly exposed to a couple of enemy units, Royalist fire was not permitted on the skirmishers since the entire unit was defined to be “in melee”. This ridiculous “in melee” notion is similar to that employed in several wonderful sets of rules… the one that springs to mind is IN THE GRAND MANNER.

Melee

After the fire phase was complete, we resolved the combat. In the melee chart, I came up with a modifier of a -3 to subtract from a 6-sided die roll, while the cavalry’s modifier was a +5. Dice were tossed, and the result was (a) that the cavalry took out a skirmisher stand, (b) my skirmishers fell back a couple of inches, (c) the cavalry received a ‘pursuit’ move, (d) they moved forward and contacted the skirmishers again, and (e) another round of melee, and my skirmishers retreated again.

Tony had ginned up a huge melee chart, with 27 potential die-roll modifiers. In an ECW game, there are several types of units, each with different capabilities against different opponents. Cavalry versus pikes had one modifier, against muskets they had another, and so on. Tony had tried to list every possible pair-off he could think of… he had, but it was too much.

At first, Tony took charge of the melee modifier table… he did all the look-ups. Everyone deferred to him when ‘melee time’ came. As the game progressed, so did the number of melees, and Bill Rankin helped out. I’ve noted this in every one of the dozen or so FF games I’ve played… the melee chart frightens most of those table-side, and they’ll sit and sit until the man-in-charge-of-the-chart comes around to adjudicate the combat. This happened in our game, and in one of the combats in which my troops were engaged, I suggested to my opponent that we should work out the combat by ourselves. No, he said, let’s wait until the big guy arrives.

And so we waited and waited and stared at each other, and finally he said, OK let’s try it ourselves. A bold man, indeed.

It wasn’t that exciting, but definitely time consuming, as we went down the modifier listing.

Digression

At the end of the battle, one of the players, who thought the game had ’potential’, suggested a way to simplify the modifier look-ups. There should be several charts, he said, each chart specific to a given pair-up. There should be a chart for cavalry-versus-cavalry, one for cavalry-versus-infantry, one for cavalry-versus-pike, one for infantry-versus-infantry, etc. In this manner, each listing need have only a very few modifiers, and the melee results could be determined much more rapidly. I fully agreed with this approach. Here! Here! Or is it: Hear! Hear! Whatever. End of digression.

In midfield, there were several combats between cavalry units. And I noted another FF characteristic carried over to TFF. The winning unit of a melee is untouched… it’s unscratched, unhurt, unharmed, unaffected. Only the loser is disorganized, or loses a stand, etc. This is the type of result found in DBA/DBM (another wonderful set of rules), in which a winning unit can engage in several melees in succession and go on and on and on and on, and by keeping on winning, remain at full strength, with no signs of wear or tear or exhaustion. Very historically accurate.

There was another aspect of FF which, at first, Tony tried to implement in his TFF. This concerned ‘pass-through’ fire... a firing unit could fire, not at where a unit is, but where it was, i.e., where it had moved during its movement phase.

This has always been confusing and irritating to the players involved. Discussion of who can fire where and when always consumes so much time and effort as to not even merit its inclusion in a game. “Hey, Tony! This unit went over there, and must I fire at it here, or can I fire at it there?”

Even battle-weary, ol’ Unca Tony gave up on this, and finally dropped it… as should FF. But I’m afraid it lives on.

Victory Conditions

At first, the victory conditions were for each side to drive the other to half-value, i.e., knock off 50 percent of the opposing stands. After some 5 turns, I counted casualties. At this time, 9 stands had been taken off the table… and 4 of them were from my own skirmishing units which had been decimated by the opposing cavalry. With 150 stands on our side, and another 150 for the opposition, 300 in all, it was going to take a wee bit of time for the battle to reach a conclusion. In part, the slow casualty rate was caused by both the fire and combat charts. I’ve already mentioned the fact that a winner of a melee stood there, untouched, with no degradation of unit capabilities. But the fire results chart, too, contributed to this.

Each stand firing yields 1 Fire Point (FP), each cannon contributes anywhere from 3 to 8 FP. You can combine cannon FP with other FP, but the total in our battle always seemed to be less than 10. And if you looked up the fire chart, on which were plotted Fire-Points-versus-a-Die-Roll, only results of a high toss of a 10-sided die roll of 9 or 10 produced a loss of a single stand. You had to accumulate about 12 to 14 FP to get the probability of losing a stand down to a respectable 40 percent. And it was almost impossible to accumulate such FP due to the short musket firing range (4 inches).

A combat result of placing a disorder marker on a unit occurred quite often, both from fire and combat, but once a disorder marker appeared, there was no additional negative effect from a second or third disorder marker. Additional markers were ignored, not even placed on the unit, and the unit simply sloughed off the damage. This is typical FF… a unit comes under fire, and turn after turn purportedly suffers damage, injury, heartbreak, etc., but after the first disorder marker appears, it magically protects the unit from the impact of further markers.

In our battle, lottsa disorder markers would show up, units would recover, the markers taken off, other markers would appear, be removed, and so on. But for the most part, very, very few stands were removed… there was no permanent impact on the target units despite the proliferation of disorder markers. I think that once during the battle, when a unit had lost several of its stands, and was in the ‘spent’ mode, and had a disorder marker on it, its commanding player diced to activate the unit, tossed very low (a lousy toss), and the activation chart said the unit fled the field and was removed from play.

As the game went on, I noticed that more and more ‘discussions’ arose as the players started to quibble with one another. The voices kept getting louder and the ‘discussions’ centered on little things, like changes in formation and movement and who is going where.

In front of my brigade, there were several cavalry units of both sides, which, turn after turn, kept charging forward, bonking heads, received a disorder marker, recovered, charged again, etc. These units blocked a full 12 inch section of frontage between the two armies… due to the cavalry’s ‘longevity’, my brigade couldn’t even move forward for most of the battle.

It’s my opinion that TFF should be ignored… as should FF… but that’s just my opinion.

Back to PW Review November 2000 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com