Whenever I use up a pad of paper, I do not throw out the cardboard backing sheet. In point of fact, I never throw out anything, but that’s another story… this article focuses on the cardboard sheets.

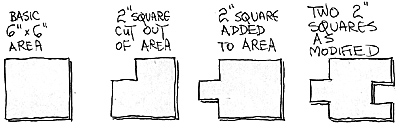

As the diagram indicates, I cut out areas from the cardboard sheets. Each area is a basic 6-inches-by-6-inches, and I’ll either cut out a 2-inch square from the basic sheet, or add a 2-inch square to the sheet. Or both.

What results is a number of areas of different configurations, which, because they can all interlock due to the common 2-inch dimensions, can be put together in jigsaw fashion to form a huge map on the ping pong table.

What results is a number of areas of different configurations, which, because they can all interlock due to the common 2-inch dimensions, can be put together in jigsaw fashion to form a huge map on the ping pong table.

I’ve accumulated a lot of these areas, and I can fill up the table with them, for use whenever I generate an ‘area game’. At a recent PW meeting, I used the areas for a slightly different purpose.

- First, I gave each side a ‘depot’… an area which was set out on the side’s baseline. Troops would arrive at the depot before setting forth across the field.

Second, each side received two home bases, located about 12 inches in from the baseline and about 2 feet from the depot. One home base was to the left of the depot, the other to the right.

Third, I placed some 6 towns on the table… these were the objectives… capture of the towns provided victory points. Except for the depots, the home bases, and the towns, the field was totally bare.

Fourth, the sides received troops. I used my 15mm ACW collection, but any ol’ 15mm units would do, as long as there were infantry and cavalry and artillery. A couple of units in the depot, a couple of units in the home bases.

Fifth, the active side could start to move its troops. But here’s the catch. Before troops could move out, there had to be areas in which to move… the side had to place areas on the field to link up the bases with the depot and towns.

Sixth. The active side diced for the number of areas it received (either 2 or 3 or 4), and proceeded to lay down its areas to form paths between the key map locations. In effect, the sides were each building their own road system across the field.

What was interesting to me was the development of the road systems. Some people wanted to first link up the depot to their home bases, others wanted to start building a road toward the towns.

Stacking limits for each of the areas on the table were 4 infantry stands, 2 cavalry stands, and 2 artillery stands. The depot, however, had no stacking limit… Units (stands) that lost a battle were wafted there, units that rallied from the Rally Zone due to a failed morale check were wafted there, units that appeared as reinforcements were placed there. A side could accumulate my entire 15mm collection in its depot.

But to move troops out, a General had to lead. No General, no movement. Marching an army across the field required a General, i.e., a figure for a commanding officer. Initially, the sides were given three Generals (one in each home base, and one in the depot). Each bound, there was a 70 percent chance that another General appeared. During one of the games, I failed several 70 percent tosses, five times in a row, and the result was that my troops simply gathered in the depot, waiting for a leader to lead them.

When, finally, a General appeared, he led off his troops (subject to the stacking limit of 4 infantry, 2 cavalry, and 2 artillery), but the remainder of my boys just stayed at the depot, still waiting for other leaders to lead.

The Generals all had 20 Loss Points (LP)… when their losses reached 20 LP, they were dead, killed in action.

The group of units led by each General were called a division. When the division was hit, it took a casualty figure, and it took more casualty figures from close combat. Once each bound, the effect of all of the casualty figures on each General‘s division was assessed, and it was at this time that the Generals incurred their Loss Points.

The assessment also resulted in stands destroyed, and stands to the Rally Zone, so that the divisions themselves were affected, not just the Generals.

Play Test

In my first play-test of the rules, which I did in solo fashion, I loosened up the movement rules to quicken up the game. Initially, I permitted infantry and artillery to advance only one area across the field, but this proved to be slow… slow… slow… and so after several bounds, I increased this to 2 areas. Cavalry stands were permitted to go 3 areas.

Another movement change was to let cavalry move without a General to lead… the cavalry were thus made independent and could move on their own.

And yet another key change was made to the system. When a side diced for the areas (2 or 3 or 4) that it could place on the field, it could forego one of its own areas, and instead of placing its own down on the table, it could take up and destroy one of the enemy’s areas, in effect, cutting the enemy’s supply lines. Something like Colonel Mosby working behind enemy lines and ripping up the railroad tracks or destroying roads.

Only unoccupied areas could be destroyed, and here was where the free-moving cavalry came in… the sides would run out their cavalry stands, placing them on their areas, and thus protecting their road systems from being torn up.

Combat occurred when one force entered an enemy occupied area. The only distance weapon was the artillery… it fired a distance of 20 inches across the table. Note that artillery range was not measured area-to-area, but in inches. What this meant was that the guns could fire across “no man’s land”, i.e., across regions on the table that had not yet been bridged by either side laying out their areas.

When artillery fired, the firing player could choose one of two options.

- One, it could decide to automatically place one casualty figure on the targeted division. No dicing required here… Simply point to a target, and if it was within range, plop down a casualty figure.

Two, if the player felt truly adventurous, he could dice for the number of casualty figures. Depending upon the throw, the number could range from zero to 2 figures.

I noted that during our game, about 90 percent of the time, the participants chose not to be adventurous, but selected the automatically-placed figure.

A favorite target for the long-range guns was opposing enemy cavalry stands that had been placed to guard the opposition’s road system. If a cavalry unit was hit, it took a morale test, and failure meant the cavalry stand was whisked off to the Rally Zone, thus leaving the area momentarily unprotected. And this meant that the firing side was presented with an opportunity to pick up, i.e., destroy, the unguarded area.

The first time out, Tony Figlia and I talked ourselves through the rules, and filled in several holes. Then, for the first grand-scale run-through of the rules, there were three participants per side, and in truth, I thought it ran remarkably smoothly for a first-time full scale presentation. No one cried aloud in anguish, no one sent any nasty looks my way, no one threw stones in my direction.

The game and its procedures, of course, is of a scale that has no historical relationship to any particular era other than that imposed by the figures used. I used ACW figures and termed it an ACW game. Use musket-and-pike stands, and call it an ECW game. Use British colonial figures and call it a British colonial game.

Many times, I’ve used the interlocking jigsaw areas in a table-top medieval campaign game in which the sides advance foot and mounted knights across the field. Each time a side moved, it laid out an area adjacent to one in which it had troops. Then the troops moved into the newly placed area, and diced to see what it found… perhaps a town, perhaps a fort, perhaps nothing.

Nothing really new here… it’s quite similar to several board game systems. The only unique thing is that you can build your own jigsaw map.

Back to PW Review December 2000 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com