"I'm afraid that sometimes

You'll play lonely games, too.

Games you can't win,

'Cause you'll play against you."

--Dr. Seuss

Last year I came across a review of Barren Victory which said that the game's command rules make solitaire play "impossible." But Ihad already enjoyed many hours of solo play, blissfully ignorant that I was attempting - and accomplishing-the impossible. (Serves me right for not keeping up with the experts in the hobby press.)

Yes, the CWB command system shines in games against a live opponent, when two different brains' plans, refracted through the Order Acceptance Table, collide. Solitaire play cannot reproduce the guesswork and gambling, the jubilation and frustration that characterizes a live playing of Barren Victory. But for that matter, solitaire play always lacks the competitive tension of two minds trying to outmaneuver each other. In this regard CWB games are no different from Blue and Gray folios.

My experience suggests that two sorts of problems are specific to solitaire play: workload and total player control. Far from making solo play impossible, the CWB and TCS command rules help me overcome these two problems.

For this article I kept notes on solitaire playings of Force Eagle's War and The Sands of War. The scenarios were similar: a modern US force attacking a Soviet (or Soviet-equipped) enemy in a positional defense. In effect, I set up a laboratory to test my ideas about solitaire.

As far as the workload goes, there's no escaping the job of moving all the units and rolling all the dice. In fact, the TCS artillery system calls for a fairly large amount of work each turn. Some might say that the process of drawing op sheets and calculating their implementation rolls adds more work, but I disagree. Putting together a decent op sheet certainly takes time, but time spent in preparing initial op sheets leads to smoother, quicker play once I start moving counters. With a script to follow, I spend less time at the table rethinking and second guessing both sides' moves. As a result, the game turns click right along and I don't get worn out even though I'm doing all the work.

Pounding Sand

For the "Deliberate Attack" solitaire scenario in FEW, I drew up two different Soviet op sheets. Another day I sat down and drew up the US attack plan. When I found some time to play, I was able to set up quickly and start blasting away. With The Sands of War, I did much less pre-planning. I played the "Makfar al Busayyah" scenario (the US versus the Iraqis) two times. The first game I dove right into by looking at the victory conditions, setting up the Iraqi defense, and prying it open with the US mech-heavy battalion task force. By turn 3, 1 had found a victory condition loophole that would let the Iraqis play for a tie, but I resisted the temptation and played on to a US victory. For the second game I eliminated the big error from my original Iraqi set-up.

Though not required to draw op sheets for the GDW game, I did record the hexes where I wanted Iraqi entrenchments, etc., and I wrote these notes: "Iraq-set up infantry screen in wadi to allow for close assault tactics. US-plot GS [general support fire from MLRS] onto 7th Army HQ [a big victory point target] for turn 2; spend first turn setting up smoke screen." I suppose I've become used to the advantages of getting my ducks in a row on paper before the shooting starts. Doing pre-game preparation certainly led to more enjoyable play. The second play-through was a much closer and more interesting game.

The Random Element

I mentioned above the problem of time spent "rethinking and second guessing both sides' moves," and this point leads me to the second, and much more important, problem with solitaire play: the gamer's total control. I mean control, not knowledge. A solitaire player is always, inescapably, going to be onmiscient about each side's plans and intentions (unless he plays with no plans, improvising all the way through). But when a fair-minded player can continuously adapt those plans to the current situation on the map, the result is typically deadlock. It is for me often enough. Though I can always surprise myself and have a dramatic moment when I suddenly notice a previously overlooked possibility (like a way to get a flank shot in a CWB game), there are no big surprises, the kind that take several game turns to develop. If a player figures out a good strategy for one side, how does he decide when, or if, to let the other side make appropriate preparations against the threat? Maybe when the disposition of the forces makes the plan obvious to anybody looking at the map? But how does the player, who already knows the plan, decide when it would be obvious to-or, harder still, suspected by-someone else looking at the map? The random element in Dean's command rules eliminates this problem.

Often I will "play fair" in a solitaire game and so end up with a pyrrhic victory. What fun. But the Command Prep table takes away some control and with it my ability to fine tune the battle to a bloody stalemate. This consideration is especially important in FEW, where the weapons are like silver bullets and even the tanks are like so many werewolves.

"Wait," you say. "Me solitaire scenarios in FEW are too short for implementing mid-game op sheets, even if the special rules didn't specifically prohibit doing so." True. And therefore I had to invent a way to produce the same good effects that the command rules automatically give in a longer game. My solution was drawing a pair of Soviet op sheets. The Red Army gets a motor rifle company, three Hinds, and some support troops. In one plan I tried a compact deployment, a thick defense in front to the Americans' first objective, with helicopters assigned to counterattack around the Soviet left flank (the potential weak spot). On the other sheet I spread out for better artillery observation and interlocking fire from the ATGMs. Both plans featured infantry dismounted and dug-in in the improved position hexes on and around the American objectives. I figured that trying to maneuver on foot or in BMPs was even more suicidal than hunkering down and getting pounded with artillery. I let these plans sit a few days so I could forget where I had laid the minefields and then drew the US op sheet. Finally I rolled a die to see which Soviet sheet I would use.

I used another randomizing house rule for air point usage, a system in the FEW game rules that, for my money, is harder to play solitaire than the command system. Each hour I rolled both sides' air points, chose the number I wanted the US to assign for air superiority, and then made a die roll for Soviet air superiority: on a 1-4 the Ruskies spent everything to contest the airspace, while on a 5-6 they spent their points half and half on air superiority and attack missions. I gave the maximum air effort better chances on the theory that the Soviet knows that US ground attack aircraft are more capable than his own and will therefore be motivated to negate that advantage when possible. As it turned out, the Americans rolled low air points each hour, and the random Soviet effort kept the A-10s and F-16s from entering the battle area.

All I had to do was add a few die rolls (one for the op sheets and two for the hourly air point allocations) to keep the US side (the "active player" so to speak) from anticipating the Soviet strategy in detail.

GDW's First Battle series allows the defender to use dummy counters set up under firing position markers [which indicate units currently eligible to use reaction, i.e. opportunity, fire]. To use these dummies in solitaire play, I would build stacks of defending units, mixing in the dummies any old way. Then I would put a firing position marker on top of each stack and shift the stacks around on the table in front of me like a shell game. Then I'd set up the stacks in defensive positions on the map, to discover where the real units were only when the attackers spotted them. This solution was rather unsatisfying because it tended to impose artificial stupidity instead of artificial intelligence on the defender. By randomizing the defense on the op sheet level rather than unit by unit, I could at least be sure I was playing against a coherent defense in FEW. The "Makfar al Busayyah" scenario does not give the Iraqis any dummies, and I didn't miss them at all. Playing The Sands of War I also went up against coherent defenses (one of which showed some weak thinking, but thinking none the less). But in this case I could not build in any uncertainty about what the attacker was going up against.

Would You Care to Order Now?

The Sands of War uses a command system similar to that in Frank Chadwick's earlier Assault (my modern tactical game of choice for several years). Units must be in command control to advance toward spotted enemy units or enter firing position. The player commands his units by keeping them near, or at least in the line of sight, of commander units. A commander can issue one order per turn, either a LEAD command that gives it a two-hex command radius from its own hex or a TRANSMIT command that gives a one-hex radius around a subordinate unit. In addition, battalion staff units can act as commanders or save their orders from turn to turn. A player can therefore choose to save up command points and spend them all at once for a big push. As the Sands rules put it, "This represents operational planning by the staff unit."

What this rule really simulates is not so much planning per se as the staff's ability to make an accurate and timely analysis of the battle, leading to the flexibility to take appropriate action as the situation changes. The fundamental difference between Sands and the TCS is that the Sands rule does not require the player to do any actual planning. The player can accumulate orders with his staff units without having to commit ahead of time to how he will use those orders. In effect, the player is under less and less pressure to plan ahead as the game goes on. During the first few turns, before the staff has built up a number of orders, leader placement is critical. Should the player keep whole battalions together and use LEAD commands, or should he get smaller battle groups moving with TRANSMIT commands? To handle these questions well, the player needs a coherent plan in mind, if not on paper. But later in the game, saved orders enable a shift to more turn-by-turn improvisation.

Cry Havoc

My first playing of the Busayyah scenario brought this point home. My mistake had been to let the T-55 battalion defend the rough ground on the Iraqi left. Though they took out an M1A1 platoon in the initial firefight these tankers folded quickly (I was using the cohesion rules, and the T-55s' morale crumbled). The Americans were behind the Iraqi main line of resistance on Game-Turn 3 (out of 8 for the scenario). The victory conditions call for the Americans to wipe out an Iraqi army HQ and occupy several objectives. Victory points add up each turn the Americans occupy their objectives, so the motive to take these with simultaneous or rapidly sequenced assaults is strong.

Upon breakthrough I used one of my two leaders to run in some tanks and Bradleys toward the HQ, which soon died under a hail of MLRS fire. Then I spread out against the dispersed Iraqi objectives,using interior lines to keep the numerically superior enemy from concentrating against me. I had originally spread out the Iraqi logistics sites (victory point objectives) on the theory that the Americans would have to take more time and cross more killing zones to get at all the objectives. But with two commanders and one staff unit with one saved command, I had four orders to use the next turn to send my battle groups off to their individual objectives. Once they were in contact and the firefight began, I needed fewer orders per turn (to get my guys into firing position). From then on it was a matter of pounding the Iraqis with firepower and capturing the objectives with easy same-hex attacks.

For another play-through, I planned to get some use out of the Iraqi infantry. A wadi cuts diagonally across two thirds of the map between the US entry edge and their objectives (an airfield, two towns, and logistics site counters the Iraqi can place pretty much at will). Wadis in Sands work like gullies in PanzerBiltz: they run through hexes instead of along hexsides, and units in those hexes can stay out of LOS of non-adjacent enemy units. By putting a thick infantry wall in the wadi, I could force the US units to come up close where they'd be vulnerable to in-hex counterattacks. Even feeble infantry can do well against armor with such attacks because they can fire at the vehicles' flank armor. The US response was to creep a commander on foot into some scrub where it could remain concealed while calling artillery and to dismount some infantry and work up along another wadi to meet the Iraqis on more advantageous terms. The tactics worked, but they consumed valuable time, Unfortunately, I ignored my informal written orders, ran a couple M3 platoons up too close before I had set up a smoke screen, and got these troops blown away. These losses would affect the later course of the fight.

The good guys did break through, but they still had to dig out defenders on the objectives and reduce all Iraqi commands to their morale break point. The US earns victory points for objectives only once he captures them all. The Iraqi earns points for killing Americans. My dilemma was between pushing hard at the risk of gamelosing US casualties and preserving my forces and hoping not to run out of time. I chose the second course and ended up playing to a tie.

Gunfight at the Palestine Corral

In my FEW game, I discovered that my op sheets ended up putting the whole American company up against about two thirds of the Soviet force. The scenario calls for the US to take both Al Hamidiya and Al Murassas. On my randomly-selected op sheet, I had set up my Soviet motor rifle company with one platoon in each of the prepared position areas on these two hills, with the MG units and their BMPs in prepared positions just west of Olive Grove Farm #1. The Hinds started near Olive Grove Farm #2 the AA teams were up front, on Al Hamidiya, and I had mines in front of Al Hamidiya and Hill 226. filling the gaps between the wadis (which are impassable to vehicles). Failure instructions for the two forward platoons were to fall back and defend Al Murassas. The defense is fairly obvious, but I had to prepare for a fire fight more than for some fancy thrust and parry work. I used a Prepared Defense, with all the infantry squads dug in.

My plan for the US used one main thrust plus support units moving on secondary axes. All forces enter from Area I on the first turn. The M1A1s and the M2s in my tank-heavy team moved up to Hill 210. There the Bradleys, along with ITVs, were assigned to provide overwatch as the tanks carried the assault onto Al Hamidiya from the northeast. The scout platoon move up through the Border Station and used terrain masking to stay out of a firefight. Their mission was to survive long enough to use their minerollers. The mortars set up near Hill 232 and the AH-64s took position behind Hill 225, read to execute pop-ups.

The US plan used three phase lines: 1 cast to west just north of Hills 215 and 219, 2 the same line but with a salient taking in Objective Pete (Al Hamidiya), and 3 from Olive Grove Farm #1 (the second position for the attack copters) east to take in Objective Cyndi (Al Murassas).

How did it go? Despite a good pre-planned barrage onto TRPs, there were some holes in the US smoke screen, and I lost an M1A1, an M107, and an ITV-- all to the same BMP -- as I tried to put someone in position to observe artillery. On a mere three overwatch triggers, the Communist crew tolled five consecutive sixes. Nevertheless, the attack unfolded as planned, despite more casualties from Soviet HE and Chem rounds. The Ruskies were shooting persistent agents on and around the US units to create a sort of "chemical FASCAM." In fact, I had to drive some US vehicles in circuitous paths to avoid the contaminated hexes. The Hinds did not come north to threaten the US staging area (the blind zones behind the hills) because of the AA risk and because they were already slugging it out with the Apaches. In fact, I knocked out two of the Hinds with Hellfires and got the other with a Chem strike. Likewise, I lost one AH-64 at NOE to Soviet chemicals.

At one point I marched a Stinger team right into a Soviet barrage, where it vanished. Oops, I had forgotten the Soviet artillery plot during a coffee break. This example show how the artillery rules don't necessarily backfire in solitaire. A player who understands the sequence of play and the mode rules often has a good idea of where to aim, so solitaire artillery fire has no unfair accuracy advantage. And it's easier than you might think to forget the details of the fire plan you wrote down the turn before. Furthermore, the op sheet graphic restricts you from dodging around target areas. On the other hand, the Soviets in my game had to cancel two out of three fire missions on both the 0920 and 0940 turns because US units, moving within the freedom allowed by their op sheet, didn't always show up in the target areas.

After getting beaten on by American firepower, the Soviets decided to execute some failure instructions. The infantry remained dug in on Objective Pete, vowing to make the running dogs work for this hill and frankly unwilling to commit suicide by flipping to move mode and leaving their foxholes. The DPICM fire was vicious. The surviving BMPs, however, fell back to Al Murassas, losing a couple vehicles to overwatch. The M3s rolled some mines, the MIAls rolled onto Objective Pete, and the end game was on.

The effects of suppression and special armor made the Soviets' AT rolls useless, and company morale was in bad shape. So the combination of fire and overruns wiped out the remaining troops on Objective Pete easily. After a shoot out with the last BMPs, the story was the same on Objective Cyndi, and the Americans won, leaving only one Soviet AA unit to escape the map. But US casualties were such that this would have been a costly win in the context of the solitaire campaign. Though the casualties alarmed me, I stuck to my op sheet, kept my faith in the principle of concentration of effort, and finally swept the map.

One point of similarity between my games is that their short durations (8 turns for the Sands scenario, 7 for the FEW) motivated me to use bolder and bloodier tactics than I'd choose for a longer game. In each game I got a good number of US units chewed up each time in my race against the clock.

One point of similarity between my games is that their short durations (8 turns for the Sands scenario, 7 for the FEW) motivated me to use bolder and bloodier tactics than I'd choose for a longer game. In each game I got a good number of US units chewed up each time in my race against the clock.

Circles Within Circles

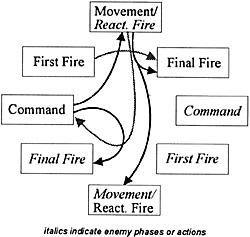

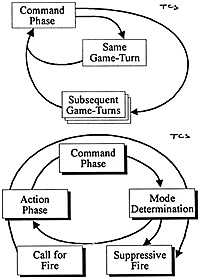

A few pictures help me visualize the similarities and differences between the approaches to both specific command rules and the decision cycle in general in Sands and FEW.

The following pictures represent the sequences of play in the TCS and Sands of War. Each box is a phase of the game turn, and the sequence of play flows clockwise. Arrows start in the phases when the player has to make a decision and point to the phase when that decision has its consequences on the map.

On the turn-to-turn level, both systems are similar. The player makes choices that will affect his units abilities, especially the ability to fire overwatch (or "reaction fire") in the present and immediately following game turn. The solitaire player can pre-visualize a whole game turn, especially in Sands, which uses no die rolls to determine who gets to move or shoot first. But the real difference, not surprisingly, lies in the long-term effects of the op sheet system. Here the decisions are fewer and more macroscopic. And, of course, the player can only guess when they will take effect. The command prep table yields the same uncertainty even when only one person is using it.

On the turn-to-turn level, both systems are similar. The player makes choices that will affect his units abilities, especially the ability to fire overwatch (or "reaction fire") in the present and immediately following game turn. The solitaire player can pre-visualize a whole game turn, especially in Sands, which uses no die rolls to determine who gets to move or shoot first. But the real difference, not surprisingly, lies in the long-term effects of the op sheet system. Here the decisions are fewer and more macroscopic. And, of course, the player can only guess when they will take effect. The command prep table yields the same uncertainty even when only one person is using it.

Lessons Learned

Since defenders can begin a Sands scenario set up in firing position, they can be remote from their leaders and still fight effectively, shooting reaction fire and defending in place. If those defenders have to redeploy, then they'll need some leadership. Similarly, TCS rules allowing implemented initial op sheets, especially Prepared Defenses, provide a strong motive to set up a good defense, one in which it makes sense to sit tight once the shooting starts.

The advantages of the Sands command system are that it limits the player's absolute control and, through the use of saved points, allows a player to achieve "surprise" if he happens to come up with a good idea, but only if he had the forethought to save up enough orders to implement it in a big way. The disadvantage is that saved cornmand points can also let the other side work quickly to nullify that surprise. Trying to play fair, the solitaire player may feel a special urge to keep both sides pretty close in the orders-saving race. The rules for GS artillery, leaders, and firing position all require forethought only into the next game turn. As a result, a scenario can devolve into a force-on-force slugfest unless, as in my first game of "Makfar al Busayyah", one side manages to exploit a mobility advantage.

What's missing from Sands is any uncertainty about the tactical situation. Sands scenarios assign the roles of Attacker and Defender, and the general shape of the battle is largely determined by the victory conditions. In contrast, Assault has a move mode/combat mode rule that lets move-mode units maneuver freely without the turn-by-turn expenditure of command points. The result is an operational dimension. In my solitaire games of Assault, I usually ended up with some sort of head- to- head clash, but the exact battlefield and attacker/defender roles were more fluid than in Sands.

The advantage of the TCS command system, as I have already hinted, is that it is a ready-made method for limiting player control and injecting uncertainty into the scenario. Its disadvantage is that it makes possible a complete orchestration of the battle beforehand. This disadvantage is acute only in short scenarios, in which planning is effectively restricted to the initial op sheets. In longer games the Command Prep Table (or Acceptance Table in the CWB games) ensures that even the best-laid plans contain some surprises. For the "Deliberate Attack" scenario in FEW I had to inject my own random element to determine which Soviet plan to use; in a longer game the standard command rules would keep me guessing about when a new plan would kick in. In such a game the specific tactical situation is up in the air at first and takes shape over time.

Interestingly, I ended up wanting to use more of the command system in my FEW game than the solitaire campaign rules allow. By 0900 (game turn 4 out of 7) 1 was wishing I had drawn some more alternates for the Soviets. And if I had had time, I might have used a new op sheet to revise the US attack and keep casualties down. Slightly longer scenarios give the solitaire player room to use the full command system. For example, I have played solitaire games of "Second Attack on Kommerscheidt" (16 turns) and "Return to Vossenack" (12 turns) from Objective Schmidt with satisfying results. I started with op sheets based on the historical orders but went on to use alternates, reserves, and new op sheets in various mixtures.

If you have a talent for improvisation and enjoy seat-of-your pants, opportunistic play, then the "impossible" task of TCS or CWB solitaire might not be for you. Grab Stalingrad Pocket or one of XTR's "panzer-pusher" games and have at it. On the other hand, you might repeat my experiment and discover that the work you put into writing orders and drawing op sheets can lead to some wild and wooly solitaire play.

When I cracked open my first Gamers game, ITQF, I (like the Barren Victory reviewer) assumed, "Hmm. This command stuff probably won't work solitaire." I went onto learn the game by playing through roll-your-own versions of Hooker's and Burnside's attacks. But I quickly discovered that playing with the command rules made solitaire a lot less cut-and-dried. To see what I mean, check out the "Sander's Field" scenario in BRS. The historical orders and the victory conditions make the big decisions for you, leaving you with a limited, albeit fun, tactical exercise.

Consulting the Oracle

OK, if my arguments don't convince you, turn to a genuine wargame expert. In his Complete Wargames Handbook (1992 edition), Jim Dunnigan gives some advice for solitaire. He suggests you analyze each side's capabilities and the victory conditions, group the individual units into larger groups, write up orders Or objectives for those groups, and establish criteria for deciding when those instructions are no longer viable. If this approach brings to mind terms like "op sheet," "task organization," and "failure instructions," youmust already be familiar with one of the two game systems I know of which, while designed for face-to-face play, already have excellent solitaire mechanisms built in.

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #8

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1993 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com