Civil War tactical proficiency is mostly a lost art. After all, it is a skill with little use in the 1990's. Still, there are those of us who do pursue it, if only to gain a greater understanding of what our simulation games are actually recreating.

Because it is at brigade level, the CWB obscures most of the tactical finesse required. Formations are abstracted, and regimental handling,etc., is resolved at a level beneath the player's control. You don't need to be proficient with the complexities of columns, lines and skirmishers, since your brigadiers do that for you.

But what is happening at that level just below the surface? Discussion by gamers within these pages and on GEnie, as well as via direct correspondence, leads me to believe that many people aren't at all sure. This article is meant to clarify tactical operations at the sub-brigade level, and explain some of our justifications for abstraction.

The infantry in the CWB has only two choices: Road Column or Line. As mentioned before, these formations are abstractions for a more complex series of tactical deployments. Road Column is actually pretty straightforward, and simply represents the four files wide formation all units adopted on the march. Line is better defined as Combat formation, since it represents more than just the two rank line that was the starting point for all Civil War combat activity. Tactical columns, skirmishers, and tactical innovation (such as wave assaults or single line deployments) are all absorbed into the standard game formation. Within a 30 minute time span, a brigade would actually adopt a variety of tactical formations, as well as mix them by regiment.

Line of Battle

So why did we call it line? Because, by the middle 19th century, U.S. army tactics recognized the combat supremacy of the two rank line. The line became the building block of all other formations, and the standard technique in either attack or defense. It was the standard battle formation of the war on both sides.

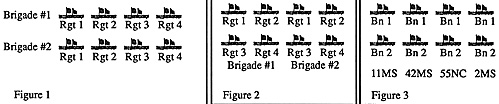

Offensively, the primary tactic is an

attack delivered by a succession of lines. Usually, a

brigade would advance in line, supported by a second

brigade, also in line, anywhere from 100 to 300 yards

behind it (Fig 1). Variations occurred such as both

brigades side by side, but on a compact enough

frontage so that each brigade would form it's own

second line (Fig 2). Davis' Mississippi Brigade at

Pickett's Charge provides further illustration of

variety. Each regiment advanced abreast, but they

were split into battalions and formed their own second

support line (Fig 3). A number of other variations

were seen as well, but the basic concept remained the

same: an initial battleline supported by one or more

follow-up lines.

Offensively, the primary tactic is an

attack delivered by a succession of lines. Usually, a

brigade would advance in line, supported by a second

brigade, also in line, anywhere from 100 to 300 yards

behind it (Fig 1). Variations occurred such as both

brigades side by side, but on a compact enough

frontage so that each brigade would form it's own

second line (Fig 2). Davis' Mississippi Brigade at

Pickett's Charge provides further illustration of

variety. Each regiment advanced abreast, but they

were split into battalions and formed their own second

support line (Fig 3). A number of other variations

were seen as well, but the basic concept remained the

same: an initial battleline supported by one or more

follow-up lines.

By the time of the war, the line had proven to be the best resolution of conflicting tactical stresses pulling in different directions. The rifled musket as the standard weapon encouraged dispersal, since longer range meant attackers endured a much greater degree of punishment in their approach. Dispersal was good since less losses were incurred. It was also bad, as it meant decreased firepower. These weapons were single shot muzzle loaders, and anything less than an absolute minimum density of about 1 man per yard couldn't deliver a sufficient volume of fire to stop a determined close order assault. Advancing infantry sometimes took as many as 25-30% (occasionally even 50%) losses in a single charge without breaking, and it still took concentrated firepower to disrupt a determined attacker.

Further argument against dispersal was loss of tactical control. A regimental commander was expected to command his unit by voice alone, and had little help. Drum and bugle calls were aids, but limited ones since they could only convey pre-determined ideas. Given this problem, dispersal spelled loss of control. Most attacks were actually halted by increasing confusion and disorganization, finally forcing advancing formations to halt and regroup.

Stepping up to the brigade level exacerbated the situation, since the brigade commander's primary communications method was his own voice as well. Most brigadiers had a couple of aides available to run simple messages, but never enough of them. In fact, the brigadier had none of the modem trappings of a command unit, such as a staff, etc.

A classic example of this tactical degradation was Jackson's famous flank attack against the Union 11th Corps at Chancellorsville. Jackson's leading formations were almost as disrupted by their success as the Federals were by defeat, and Jackson himself was wounded trying to restore control and press home the attack. Tactical control remained a problem throughout the war.

The Elusive Column

One of the most confusing aspects of Civil War tactics is interpreting the word column.

Period accounts are full of references to "assault columns", advancing or retreating "columns of enemy infantry", etc. In virtually all instances, what these writers are referring to are actually troops in line. For instance, Upton's famous attack at Spottsylvania is referred to, throughout his and his subordinates' accounts, as an assault column. In a larger sense, that's what it was. In detail, however, it was a formation of 12 regiments, all deployed in battleline, in four separate lines of three regiments each. Upton utilized a traditional attack formation with three supporting lines instead of just one. The real innovations of this assault were that Upton chose his point of attack carefully, rehearsed it with the subordinate commanders, and crafted a detailed plan of execution after the initial defenses were stormed. Pickett's Charge was not a column assault either. Pickett, Pettigrew and Trimble's men all advanced in battleline. One, and in some spots, two, supporting lines followed the first, an organization that broke down upon reaching the Union positions. The latter stages of the attack saw the rebels deployed only in a milling mob, (in some places 15 or 20 men deep!) with commanders arbitrarily assuming control of local groups.

Even when not using column in a generic sense, the term is still a slippery one. Aside from road column, tactical columns consisted of columns of platoons, companies, divisions, and battalions. In each case, the regiment formed a battle line, and then split into the indicated width, (one platoon, one company, two companies, or half the regiment) and formed one behind the other. For instance, a column of companies would be a series of battlelines one company wide by ten companies deep. Each company was split into two platoons, and the term "division" used here refers to a two-company sub-organization within the regiment, not the larger, multi-brigade formation we're all used to. Additionally, all columns could be either "closed" or "open" order. A closed column left no space between the battlelines, in effect creating a solid block of men. An open column left room enough to deploy between the lines, providing more tactical flexibility.

The most common use of column is deployment in column of divisions, (again, the two company version) usually by a regiment or brigade not yet posted in a defensive position. The column of divisions was preferred for units in this reserve status because it massed troops in a small area and yet still provided maximum flexibility to move in almost any direction quickly. As an example, the 11th Corps at Gettysburg was initially deployed by regiment in column of division, as they awaited developments on July 1st.

Actual use of columns in combat is a much rarer phenomenon. Defensively, of course, line was the formation of choice, since it delivered maximum firepower. Offensively, columns were occasionally used, mostly later in the war as commanders experimented in order to overcome increasing defensive advantages.

In 1864, at Kennesaw Mountain, Sherman

launched a series of simultaneous attacks at the

Confederate defensive works. Each assault was a true

column, spearheaded by a brigade formed in regiments

in column of division. With a two company frontage

(probably 50 men ) and a depth extending back for the

entire brigade, followed by other supporting brigades

in a more traditional line deployment, the concept was

that of a spear-point that would penetrate the enemy

line much more easily than a linear approach.

Unfortunately, the simple laws of physics don't

account for morale, fear, and other non-quantifiable

conditions, and each of these attacks was a bloody

failure. They were preceded by heavy artillery

preparation, which had little effect on the Rebel

earthworks, and the approaches were over good fields

of fire. In most cases, the head of the attack faltered

once it reached some relatively sheltered spot, and the

troops went to ground and couldn't be urged forward

anymore.

The largest column attack of the war

occurred at Spottsylvania. Grant, observing the relative

success of Upton's initial attack, chose to duplicate the

feat with an entire corps. At dawn on May 12th, 1864,

the Union 2nd Corps advanced in a huge block of

troops. Each regiment was deployed in a closed

column of divisions, and the whole force massed.

Birney's 3rd Division was deployed in line on the

flanks, to provide protection of the main column. The

mass overwhelmed the first line of Rebel defenses, and

was finally stopped by determined CSA

counterattacks. The Union troops were in turn flung

back to the initial CSA defenses, and one of the most

grueling struggles of the war ensued. For a full day,

Union and Confederate troops held opposite sides of

the same defensive line, and fought viciously.

Grant's initial success was due to several

outside factors. First, the bulk of rebel artillery had

been withdrawn the night before because Lee thought

his opponent was maneuvering again and wanted to be

able to leave quickly. Most of these cannon were only

returned to the line in time to get captured without

firing hardly a shot. Second, the Federals advanced

under the cover of a dense fog that protected them

from Rebel sight until the last 50 yards or so, ensuring

surprise. Third, many CSA regiments' ammunition

was rain-soaked, greatly reducing their fire. The

Federals faced only sporadic enemy fire, and suffered

comparatively few losses on the initial advance.

Disorganization was oneof the problems

Grant hoped to solve by the use of the massive

column formation yet it was disorganization that

ultimately stopped the Union advance. The Rebel

counterattacks were delivered by a severely inferior

force, but one that retained its tactical organization.

The Union formations were so tightly packed together

that sub-units couldn't maneuver or deploy. In effect,

Grant's column could only be handled as one huge

unit.

A massed series of lines of this strength

would have probably moved much slower than normal,

given the vast density of the formation. An advantage

of the close proximity was a increase in the ability of

the officers to control their regiments and thus

maintain the quiet needed to keep the element of

surprise. The main drawback lay in the fact that such a

block was virtually incapable of changing formation

or direction without lots of time and plenty of room.

From a simulation sense, while this attack

did use a column formation, it still possessed the

frontage and firepower of several brigades (at least) in

line, and the net effect on volume of fire was not very

significant. In the CWB this formation would be better

simulated by stacking and massing as many units as

possible together in adjoining hexes, rather than using a

column formation. Note that Grant did notrepeat this

particular experiment again, signifying, I think, the

ultimate failure of the tactic.

Antietam and Burnside's Bridge

One other famous column attack bears

examination, especially since this one was delivered in

road column. At Antietam, two regiments of Federal

infantry stormed the Lower (Bumside's) Bridge in road

column, the widest formation that could move across

the bridge. This example has been used at least once to

call for a revision of the CWB to make column attacks

more favorable for the attacker. A closer look,

however, fails to justify the change.

In effect, 350 Georgian infantrymen (only

half of Toombs' Brigade was there, for you owners of

In Their Quiet Fields) held off no less than 3 Union

brigades - some 4500 to 5000 men - for three hours.

Serious attacks commenced about 10:00 a.m., and

finally about 1:00 p.m. the two Federal regiments

rushed the bridge. It took no less than four separate

charges to gain just the east end of the bridge from

which the assault across could be made. ne Union

assault column was greatly aided by the suppressive

fire of some 2000 other troops in their final charge, by

the fact that the Rebels were running out of bullets,

and by a Union flanking column that crossed the creek

into the Georgians' rear about the same time. In the

action overall, the two Federal regiments-the 51 st

New York and 51st Pennsylvania-lost 207 of the 670

men engaged, most of them on the rush across the

bridge itself. The two Georgia regiments--the 2nd and

20th--lost about 80 of their 350 engaged. This loss was

spread out over the full three hours of action. The facts

speak for themselves.

For a final dose of confusion, the larger

tactical formations also used column formations. For

example, in the Wilderness, may 5th 1864, Hancock

intended to attack with his Union 2nd Corps with

divisions abreast in column of brigades (Fig 1). More

simply put, each division was to attack side by side,

on a one brigade frontage, three brigades deep. The

regiments, however, would all be in line. Given the

tangled condition of the Wilderness, this would have

been the best assault formation for tactical control, but

circumstances and command confusion prevented

Hancock from fully deploying his men before he had to

advance. Instead he moved most of his divisions on at

least a two brigade frontage, and suffered accordingly in

terms of loss of control.

The other major formation for infantry was

the skirmish line. Some gamers misunderstand

skirmishers' purpose because of the inherent

limitations of the games themselves. Most of the

historical works I've read miss the point of skirmishers

entirely, regarding them as a combat formation. The

primary purpose of skirmishers was tactical battlefield

reconnaissance, a completely unnecessary function in a

game without hidden movement.

Skirmishers were deployed to provide

defenders early warning of an attack, or to find the

enemy's main defensive positions when advancing.

Once contact was established, the skirmishers were

reabsorbed into the main line. On occasions,

skirmishers would be detached to screen a flank,

something both sides did in the fight for Little Round

Top. The reason for their lack of battlefield

decisiveness is simple: firepower. Doctrine called for a

skirmisher density of about 1 man per 5 yards,

meaning that a battleline advancing on a skirmish line

would have a 15 or 20 to 1 advantage. John K. Mahon

quoted a telling statistic, claiming that lines held their

ground even after suffering 40% losses, while

skirmishers retreated after losing 2%. Of course they

did. They completed their task of finding the enemy

and promptly reformed into the main formation.

Skirmish fights were common in between

the armies' main lines, as both sides probed for

information. Sometimes, fights erupted over buildings,

clearings, etc., which would give a side an advantage in

their intelligence mission. Most skirmish actions

involved at most 100-200 men, and are insignificant in

the larger scope of a game at brigade level. In games

where 100% intelligence prevails, skirmishers are a

formation without a purpose and tend to detract,

rather than add to, an effective simulation.

Much has been written about how the

Civil War presaged the tactical deadlock of WWI, and

how some Civil War era commanders began to search

for alternatives to the traditional battleline. For

instance, as early as February of 1862, a Union

command at Fort Donelson advanced on the enemy

fortifications using short rushes. Dividing his forces

into two wings, the Union commander bounded the

men forward in a series of strengthened skirmish lines.

They captured the Rebel initial defensive line,

convincing the Rebels that their tactical situation was

hopeless. Of course, the Rebel defenders held the line

only with skirmishers as well, since the bulk of the

Confederate troops were sent to the other flank to aid

in a breakout attempt. Hence the resistance to the

Union advance was very weak.

A more intriguing glimpse of tactical

innovation appears in the Wilderness, May of 1864.

On the morning of the 6th, Longstreet's Corps arrived

just in time to counterattack Hancock's Union assault

and repulse it. Longstreet claimed in his memoirs that

the Union forces, once thrown into retreat, were

pursued and held at bay by six Rebel brigades using

"reinforced skirmish lines" as their main combat

formation. Longstreet said that these lines were greatly

strengthened, and then continuously reinforced by the

remainder of the brigades'men, held some distance to

the rear in reserve.

Unfortunately, no contemporary battle

reports from the Wilderness either corroborate this

statement or explain it in more detail. I hope that some

other source (Confederate Veteran Magazine, the

Southern Historical Society Papers, or some regimental

histories) can elaborate on this event, and will continue

to look for such.

If Longstreet's recollections are correct,

this would be a significant and large scale effort to

convert the skirmish line into a primary combat

formation. However, certain important factors, unique

to the situation, aided Longstreet's efforts at

innovation.

Longstreet's initial counterblow was

delivered across relatively clear ground, and id

traditional battleline. The Federals, already

disorganized by their own advance, were thrown into

major confusion by the timely Rebel attack. Once in

retreat, it proved impossible to rally the disorganized

Union regiments and form an effective line short of

their own breastworks (which were erected

immediately by the Union troops, before they began

their attack).

Hence, a relatively weaker Rebel line could

maintain enough pressure on the retiring skirmish line

to hold the Federals in check while he prepared a

flanking attack which struck in the late morning. The

skirmishers were called upon only to hold for about

two hours before a stronger, more powerful blow was

delivered by other Confederate troops, who were

deployed in a traditional two-rank line. As with

Grant's massed column above, Longstreet's skirmish

techniques were not repeated at the same multi-division scale he described.

This did not mean tactical innovation was

dead. The most significant strides forward came from,

of all places, the Federal mounted arm. In 1864 and

especially in 1865, Sheridan's Union troopers began to

take an increasingly aggressive role on the tactical

battlefield. Cavalry began to deliver dismounted

assaults in dense skirmish lines, sometimes coupled

with mounted charges to further disrupt defense. At

Nashville, Thomas relied on his veteran Yankee

cavalrymen to attack Hood in the rear, utilizing their

superior tactical mobility to outflank the Rebels. In the

Appomattox campaign, there are several instances of

dismounted cavalry driving back regular battle lines of

formed infantry.

All of these above examples share certain

significant tactical similarities, namely in firepower

density. Instead of the above noted 1 man per 5 yards'

density, these later experiments developed a much

greater mass of roughly one man per yard. Now, a

regular battleline's advantage was reduced to 3 or 4 to

1. Of even greater significance was the fact that, for the

Union cavalry at least, greatly increased firepower was

achieved by widespread use of 7-shot Spencers, or

better yet, 16-shot Henry rifles.

The reinforced infantry skirmish lines

tended to only succeed against weak or disorganized

resistance because a solid defensive line still maintained

firepower superiority. The cavalry lines, with their

better weapons, managed to best formed infantry due

to their actual advantage in volume of fire.

The defense developed an innovation of its

own more rapidly and far more universally than the

offense - trenches. No one figured out how to defeat an

adequately manned full defensive line once

entrenchment became the order of the day. Grant's

ultimate tactic was to simply stretch his opponent's

lines until there weren't enough defenders to go around.

This solution could only work when the attacker

possessed the massive manpower advantage the

Federals held by the spring of 1865.

These tactical experiments were brought to

an end by the collapse of the South before any

sweeping offensive trends emerged, and so they

achieved relatively little notice at home or abroad.

Later European wars took center stage, and much of the innovation

displayed in 1865 never got the examination it should

have.

The CWB overtly ignores these trends for

several reasons. First, the system is designed to portray

only the combat of the first part of the war, before the

advent of full trench warfare. Second, the main tactical

weapon remains the muzzle-loading single shot rifle,

against which skirmish lines remained inferior in terms

of firepower. Third, some tactical adjustment is assumed

within the brigade counter itself, as described above in

discussing battlelines. The real tactical innovation would

have placed multi-shot breach-loading weapons into the

hands of infantry units on a massive scale, something

only the Union could have achieved. Unquestionably,

this would have drastically impacted on the fighting and

the war as a whole, but is not a speculation the CWB is

designed to address.

Much debate has centered around the need

for a density adjustment modifier to fire combat, a

concept with which I vehemently disagree. Fire combat

is not some random distribution of projectiles over a

given specific area, but rather a controlled, aimed and

directed action against the enemy.

Suppressive and area fire concepts belong in

the modem age, companion to the "empty battlefield"

phenomenon. Civil War combat occurred between

formed units who could see each other, or at least knew

each others' approximate locations. As I previously

pointed out in my article on woods effects (OPS #1),

units who couldn't see each other tended to close in until

visibility was possible, and hence so many actions in

trees occurring at ranges of 10 yards or less. Finally,

units in combat are not assumed to automatically spread

out to fill all available area, but instead maintain unit and

battleline integrity. They are not random molecules, but

rather combat soldiers who understand the importance of

tactical control.

The most common mistake gamers make

about the CWB is to assume that all of the men a brigade

represents are automatically deployed in a single line, no

matter how strong the unit. In reality, the maximum

number of men in line that can fit into a standard CWB

hex is from 700-800, the lower end of an A fire level.

Within the counter, the excess troops are considered to

be deployed in supporting lines, or in adjacent hexes if

using extended lines. If an "AA" fire level unit extends

line and occupies an adjacent hex, it hasn't reduced its

front line density at all, but instead now occupies double

the distance with the same density, and having twice

as many men in the front line. Excess manpower

(assumed to be in regiments forming the supporting line)

is far less likely to suffer fire losses.

When the front line loses men, these supporting

troops step in to fill the gap. Effective commanders even

tried to rotate frontline duties between regiments

wherever possible. Men of the Union 12th Corps at

Gettysburg, defending Culps' Hill on the night of July 2nd-

3rd, did just that.

Conversely, units with less than 800 men (a

"B" or "C" fire level, for instance) do not automatically

spread out so that there is a uniform man per yard

density across the length of the hex. Instead, the units

remain in close order formations, since this is the only

formation that can hold or take ground against other

formed infantry. Some spacing between formed

regiments may well occur, as a brigade commander

struggles to hold the ground assigned him, but each

element of the unit would still present a formed, close

order target.

What better note to end on for infantry

formations than in discussing the ubiquitous square. A

holdover from the age of Napoleonic Glory, it soon fell

into disuse in the Civil War. (Sir Arthur Lyons

Freemantle, of Her Majesty's Coldstream Guards, was

greatly put out that American infantry regarded the

square as an archaic formation.) The Union Regular

Battalion employed it at First Bull Run while covering

the collapse and retreat of the volunteers, but it soon fell

into disuse, mostly because mounted cavalry had little

battlefieldrole. Mounted men proved too vulnerable to

long range fire from rifled weapons, and charges rarely

occurred. Still, there are occasional examples of its

employment throughout the war.

It was not that the theorists weren't aware of

the tactical implications of the rifled musket, or the

increased advantage it gave defenders, especially

entrenched ones. Foreign observers from the Crimea

noted both, most significantly George B. McClellan. The

problem was that they failed to find a tactical

combination to restore offensive action to primacy.

It was still assumed by everyone that a

spirited bayonet charge could capture entrenchments

quickly, before the attackers suffered too heavy a loss.

(This theory was the primary motivation behind both

Upton's and the 2nd Corps' Spottsylvania attacks, for

instance.) A great degree of blame can be found in the

Mexican war, where, time and again, U.S. troops

overwhelmed entrenched Mexican defenders. Ultimately,

these successes had more to do with better U.S. morale

and training than anything else, and when more equal

troops met in battle, such tactics usually failed to carry

the day.

Of course, the bayonet charge did have

successes, but this more often depended on mitigating

circumstances than on the spirit of the attack. Both of

the Union assaults mentioned above, for instance,

achieved initial success because they came as complete

surprises to the Rebs. Upton had less than 100 yards

of approach to cross, and 2nd Corps closed to within

50 yards before being discovered.

Entrenchment was an ongoing learning

process as well. As the war progressed, more elaborate

defensive works became the norm rather than the

exception, until the trench arrived in all it's dismal

glory. See OPS #2 for a more detailed look at defensive

works.

Civil War tactics have received much less

notice by historians than other aspects of the war.

Still, some excellent works have examined the topic,

and in far more detail than I have laid out here. The

following are among the more readily available. John

Kisner, in Operations #3, discusses an article

by John K. Mahon entitled "Civil War Infantry

Assault Tactics", from Military Affairs

magazine. Mahon's article is a quite useful analysis,

though limited. The best recent book that addresses

the subject is The American Civil War and the

Origins of Modern Warfare, by Edward

Hagerman, published in 1988 by Indiana University

Press. Hagerman discusses a variety of aspects about

the war, notjust tactical applications, and reaches well

supported conclusions.

McWhiney and Jamieson's Attack and

Die is more bizarre, but still useful. Their tactical

analysis is quite good, and they're correct, I think, in

pointing out that the South attacked too much, but I

have trouble buying into the Celtic bit. Both sides

failed to grasp the fundamental shift in war, and

launched foolish attacks, but it had more to do with

West Point than genetic memory. Read the first half,

throw out the second.

George R. Stewart's Pickett's

Charge, widely available, does a fine job of

examining a specific attack in detail. There are some

other efforts out there, but I found them too general to

be very useful. The period tactical manuals, while dull

to extremity, are the only way to thoroughly

understand the doctrine. The most comprehensive is

Casey, Infantry Tactics, published in 1863,

and covering everything from the school of the soldier

up to brigade maneuvers. Some turn of the century

works exist, but they are rare and hard to find. For

instance, Organization and Tactics, by A.L.

Wagner, published in 1895. In all honesty I have only

read excerpts from it and cannot comment on the full

content.

Our Friends, the Skirmishers

The First Modern War

The Density Question

Squares

Digging In

We Have Our Sources

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #5

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1992 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com