Introduction

This article is intended as a primer into the world of

military planning. Although the techniques and procedures

discussed can be used for all types of wargames, they work best for

operational level simulations (i.e., OCS and SCS). My hope is that

these ideas will spark interest and debate, and perhaps motivate

some of you to develop your own systems. This article is not

meant to be the definitive word on planning, nor is it my intention

that the processes presented here be used as a template by all

wargamers. Having said that, I felt compelled to share my successes

and failures with my "kindred spirits" out there.

This article is intended as a primer into the world of

military planning. Although the techniques and procedures

discussed can be used for all types of wargames, they work best for

operational level simulations (i.e., OCS and SCS). My hope is that

these ideas will spark interest and debate, and perhaps motivate

some of you to develop your own systems. This article is not

meant to be the definitive word on planning, nor is it my intention

that the processes presented here be used as a template by all

wargamers. Having said that, I felt compelled to share my successes

and failures with my "kindred spirits" out there.

Before getting into the meat of the article, let me be perfectly clear about something: the concepts and procedures presented here are not my own. Rather, they are a compilation of things I have learned over a 13-year military career. The ideas and processes you're about to read contain elements of Navy, Marine Corps, and Army procedures. There's even a sprinkling of Soviet doctrine (you know, just for flavor!). In this article I will present theories and concepts, and attempt to back them up with "real world" examples. I hope you like it!

Principles

Why plan? After all, don't we play wargames to get away from the drudgeries of life and feel the exhilaration of rampaging through our hapless victim's rear areas with the wind in our hair (what's left of it) and a knife in our teeth? On a personal level, I plan my games for two reasons: First, it greatly improves my play. When I've used this process the results have almost always been favorable.

Even when I've lost, the games have always been close. I haven't won every time, but there are more notches in the W column than not. However, when I haven't used this process, I've gotten my butt handed to me! Second, planning enhances the feeling of "being there," feeling a part of the action. One of the reasons I play wargames is to explore, in near real time, the "what if" scenarios we all pose to ourselves.

A well thought out plan aids in this endeavor, thereby enhancing my enjoyment of the game. On a higher conceptual level, planning has a number of benefits. To begin with, planning gives us a framework for solving problems, specifically the gap between current and desired state. It gives us a methodology for deciding how we are going to win. Also, planning allows us to use our forces effectively, keeping in mind the principles of war, namely, mass and economy of force.

Lastly, planning helps us stay focused on the objectives. It's very easy to get caught up in the emotion of a swirling knife fight in the middle of the African desert or the Russian steppes. Adherence to the concepts of a plan, formulated before the casualties start to mount, keeps us from dancing to our opponent's tune.

In order to gain a better understanding of planning and how it can help, it is necessary to look at some planning concepts.

Deliberate and Rapid Planning

All planning is based on the variable of time. When sufficient time exists, deliberate planning is used. Deliberate planning is conducted before the initiation of an operation, like before a game/scenario starts. Deliberate planning has the advantage of giving the individual a good deal of time to explore various courses of action (COAs). Also, it allows the player to fully orient himself to the situation. However, deliberate planning has some drawbacks.

It is heavily dependent on assumptions: What is my opponent going to do, how will he react, and in some cases, where will he set up? Because of this, deliberate plans tend to not be valid for very long. Once the shooting starts, the player will transition to rapid planning. While less formal than deliberate planning, rapid planning is based on actual events and not assumptions. However, due to the time constraints, rapid planning may overlook viable COAs.

Coupling

This term refers to the degree to which two or more actions are interrelated. Two terms describe the level of coupling in a plan: tight and loose. Tight coupling describes a situation where a number of activities are closely related to one another; the different actions must occur in a specific sequence at specific times. Tightly coupled plans make very good use of available assets, but at the expense of flexibility. Because they are easily upset by the friction of war, tightly coupled plans lose their value as the dynamics of a situation increases.

Generally, deliberate plans are tightly coupled. By contrast, loosely coupled plans are useful in highly fluid situations. Because the actions are not highly dependent on one another, loosely coupled plans work better in unpredictable situations, albeit at the expense of combat efficiency.

Sequencing

In an operational-level game, victory is not achieved by a single action. Rather, a series of events must occur. The transition between events is called sequencing (sometimes called phasing). The phases of a campaign link the individual events together within the context of the larger campaign. In other words, individual tactical victories are meaningless unless they help achieve some intermediate goal, which itself contributes to the overall design of your campaign. These phases are event, not time, oriented.

Here's an example of the concepts we just covered:

As of this writing, I'm playing Crusader as the Commonwealth. The following is my broad plan.

- Phase I Rapidly capture Sidi Aziez and Sollum.

Establish strong armored presence on the ridges in the central

part of the map and west of Bardia. This was a deliberate plan

which was tightly coupled. I identified specific units to carry

out the various tasks. This phase did not last beyond Turn 2.

Phase II: Establish strong defensive positions around VP hexes. Build up strong reserves for the Phase III offensive. Keep Tobruk garrison on the defensive, unless he starts pulling significant forces away to deal with other threats. Use mobile forces to attack targets of opportunity and keep him off balance. My goal in this phase was to chip away at his strength, while at the same time build up my own strength. A primary desire was to not give him a chance to beat me up with his powerful panzer units.

Phase III: Conduct a three-pronged offensive westward to capture the following VP hexes: Gambut, Sidi Razegh, and El Adem. The offensive will kick off when he is unable to meet all 3 thrusts. The Tobruk garrison will conduct harassing attacks, if not an all-out attack, as a supporting operation. The last phase was my "big push." If Phase II went well he shouldn't be able to stop all 3 thrusts and keep Tobruk surrounded. In maneuver warfare terms, the intent of Phase II was to soften him up for the Phase III dilemma.

Misuses

Although plans can be great player aids, plans can be disastrous if not used properly. Listed below are four common misuses of plans:

- 1 . Attempt to forecast events too far in the future.

Planning is not a crystal ball, and plans should not be perceived as visions into the future. A recent study of Army operations showed that division and brigade plans were valid for only 65% of the time intended.

2. Plans contain too much detail.

There is a natural desire to leave no stone unturned in the quest for creating the "greatest plan ever." Unfortunately, too much detail clouds the issues and defeats the value of a plan. Remember, we're talking about operational concepts, not specific moves. It would be wise to heed the words of Helmuth Von Moltke "no plan survives contact with the enemy."

3. Plans are used as a battle script

Anyone who has ever been in a position of military leadership will tell you it's hard enough predicting what your own people will do, even after you've told them! There's absolutely no way we can predict what our opponents will do. The best we can hope for is to identify general patterns (cautious, aggressive, likes high ground, etc.).

4. Plans become too rigid.

Once a plan is written down, it is not set in concrete. As we will cover later, the planning process is a continual loop of going back to the drawing board and starting again. It is the process that is valuable, not the product. As General Eisenhower once said "Plans are nothing. Planning is everything."

Process

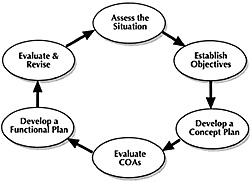

Now that we have the theories and concepts of planning firmly embedded in our minds, let's look at the actual methodology. At right is a schematic of the planning process.

Now that we have the theories and concepts of planning firmly embedded in our minds, let's look at the actual methodology. At right is a schematic of the planning process.

The first step in the process is Assess the Situation. In all wargaming instances the broad setting is given to you. Nonetheless, you must further analyze the situation if you are to formulate an effective plan for winning. Employing the acronym METT-T(L) is a powerful tool in orienting ourselves to the operational situation. The acronym stands for Mission, Enemy, Terrain/Weather, Troops, Time, and Logistics. Here's how it works:

Mission:

- What type of mission do I have? Attack, Defend, Exit points, etc.

- How will victory be determined? Is victory tied to geographic objectives, enemy/friendly casualties, or both?

- What victory level is feasible? What can realistically be achieved?

Enemy:

- What are the enemy's weaknesses?

- What are the enemy's strengths?

- What are the enemy's objectives?

- What is the enemy's troop disposition, and does it indicate what he wants to do?

- What are his probable courses of action?

- What is his center of gravity?

Terrain and Weather:

- What key terrain exists?

- How will/can the terrain affect mobility, and are there identifiable avenues of approach?

- Are there any critical road junctions?

- What effect will weather changes have on my scheme of operations?

Troops:

- What are my strengths and weaknesses?

- How can I capitalize on his weaknesses?

- How can I neutralize his strengths? Positional/Functional Dislocation

- What is my center of gravity?

Time:

- What is the scenario length, and how will it be a factor?

- Is there a time when significant disparity in combat power exists? When?

- When will reinforcements arrive? His/mine

Logistics:

- Does the supply situation favor one side?

- How vulnerable is my supply?

- Can I attack his supply sources, and will it bring about positive results?

The tough part comes in answering some of these questions. I will provide some insight to how I do it. Keep in mind that these are only my thoughts and techniques, not standard military SOP.

One of the more tedious parts of assessing the situation is determining the relative strengths and weaknesses of the two forces. I use a simple "bean counting" technique that gives me a pretty good overall picture. I tally up the total number of combat points (offensive and defensive in the case of SCS), the average number of combat points, and the average movement rating. These numbers can be modified by any number of variables, such as reaction ratings, the capabilities of the other player, etc. The point must be made that this "bean counting" is not an attempt to wage war by the numbers (i.e., attrition), but rather a method to give a good overall picture of the characteristics of the belligerents.

Determining relative strengths is tedious but not very intellectually taxing. This cannot be said about determining the center of gravity. I will not attempt to give a lecture on the facets of maneuver warfare. However, the concept of center of gravity is crucial in understanding how to win. Basically, the concept goes like this: if you take out (neutralize, destroy, capture, etc.) the enemy's center of gravity, he becomes incapacitated and unable to wage effective warfare against you. Achilles' heel was his center of gravity.

The center of gravity is not a source of strength, but a critical vulnerability. In operational-level games the center of gravity is often a headquarters or supply, although not exclusively so. To determine you center of gravity, ask this question: "What can I not do without?" This is your center of gravity. To determine the enemy's center of gravity, put yourself in his shoes and ask the same question. When you get an answer, this is what you should seek to attack. You now have an accurate assessment of the situation.

The next step is to Establish Objectives. This is the point where the commander (you) allocates his resources. Unless your opponent is criminally inept, you will not have sufficient resources to do everything. If you attempt to simply bull over your opponent, you'll probably end up with nothing. You should decide what forces you want to use, and for what purpose. Identifying objectives helps you to allocate your resources wisely. The combat resources at your disposal aren't limitless. All those counters that you painstakingly punched out and arranged on the map will start disappearing soon enough.

In short, establishing objectives identifies what you want to do. If you don't identify specific objectives, then what you'll end up doing is simply moving your stacks adjacent the nearest enemy units and recreating Rock 'em Sock 'ern Robots.

If Establishing Objectives identifies the what, then Developing a Concept Plan identifies the how. Your concept plan begins by developing at least three courses of action (COAs). A COA is a statement of intent as to how the commander will utilize his forces to realize his objectives. To be viable, each COA must be:

Realistic: Do the forces involved have a reasonable chance for success?

Specific: Does the COA support the attainment of the objectives?

Distinct: Does the COA differ from other options?

In developing COAs it is helpful to touch on the following points to ensure they are viable:

Decisive points: These can be a time, a place, a unit, or a combination. Decisive points will either neutralize or directly threaten the enemy's center of gravity.

Supporting Efforts: Not all of your force will be directly involved in the main effort. What can be done to maximize the main effort's chance of success? Supporting efforts (feints, blocking forces, protecting key terrain) answer this question.

Forces Required: Here, the commander assigns main force units and supporting forces (air, artillery) to various activities.

The last step is to draft a COA statement for each COA. These are simple sentences that answer the following questions: Who (units involved), What (assigned tasks), When (time phasing the operation), Where (assigned areas), How (scheme of maneuver, axis of advance, main effort), and Why (how will it achieve the objective).

Once you have developed several options as to how you want to conduct the campaign, it is time to Evaluate COAs. In evaluating COAs I use a fairly simple business planning tool known as a Interrelationship diagraph-a fancy name for a chart that compares two sets of variables. In this case, the variable to be compared are the COAs and the factors METTL(T). Here's bow it works: out of my 3 COAs, one of them will be the best in terms of the mission.

For the purposes of this exercise, let's say it's COA 1. 1 would then put a 3 in the Mission box under COA 1. Next, I put a 2 in the box under the COA that is second best for mission, and a 1 for the least desirable COA.

I continue this process until my matrix is complete. It then becomes a simple matter of "high score wins." The following chart illustrates the concept.

| Attribute | COA1 | COA2 | COA3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mission | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Enemy | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Terrain | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Troops | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Time | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Logistics | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Overall | 13 | 12 | 11 |

Using this process, I can see that COA 1 is my best bet. However, there may be extenuating circumstances that can effect the outcome. For example, what if "Troops" is by far the most important factor? I may want to weight this, for example multiplying the result by 2 (or whatever). The point is that this is a tool for you to use: there's no hard and fast rule about how to set it up. Also, be cautioned not to let the tool make the decision for you. When all is said & done, take a step back and make a gut check, an intuitive "Does this make sense?"

Develop a Functional Plan

Once you've decided on a COA, it's time to Develop a Functional Plan. You know what you want to do and you've decided how you're going to do it; you now need to decide the where and when. As you're doing that keep in mind that the farther out you plan, the less control you will have. Remember the drawbacks of planning and the concept of coupling. It's O.K. to identify specific units for particular tasks. For example, using 3 infantry divisions as a breaching for and reserving 2 panzer divisions for exploitation. However, it would be unrealistic to think "On turn 6, the 12th SS Panzer will capture Bastogne"; that's projecting too far in advance.

Another concept I use in this phase of the planning is that of critical events. A critical event is a show stopper: something that will drastically alter the relationship between my forces and the enemy's, thereby upsetting my concept of operations.

Critical Events can be time/ place oriented (capture X by turn Y), or they can be unit oriented (the destruction of certain combat elements, yours or his). Your list of critical events should not be very long, maybe 2 to 5. If you've done solid planning you won't be hinging success on unrealistic expectations or relying on luck. Nonetheless, our stalwart foes are an unpredictable lot, and may throw us an unexpected curve. If a critical event does take place, your planning cycle now goes into the last phase, Evaluate & Revise.

Evaluate and Revise is simply measuring your plan with what's actually happening. As already mentioned, critical events can automatically put you in this phase. If that's the case, the evaluation has already been done for you and it's time to revise-- quickly!

Most of the time, however, our carefully laid plans unravel slowly; a stubborn defense here, a bad die roll there, and before you know it, your back is against the wall. If you can discipline yourself to evaluate your plan you'll be able to recognize when you're going awry. The key is to recognize a trend, not react to specific events. One bad event does not ruin a campaign; nothing works out precisely as planned.

For example, during the Normandy invasion the U.S. airborne units failed to reach most of there specific objectives. However, they were successful in the more general objective of tying down German reinforcements and keeping them away from the beaches. Consequently, the invasion came off more or less as planned. Don't allow yourself to take counsel of your fears; keep looking at the big picture.

If you do need to revise your plan, you'll have to go through an abbreviated process. Much of the bean counting and numbers comparisons goes away. This does not mean that you should get sloppy with your planning. It's simply a recognition that time constraints don't allow for you to get into the nitty gritty.

Hopefully this will give you some ideas to help you play better. As I've said, it works for me. Feel free to modify and amend the process.

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #32

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1999 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com