"Anyone who has to fight, even with the most modern weapons, against an enemy in complete control of the air, fights like a savage against a modern European army."

Air power is an important factor in operational combat, and the OCS offers some of the best representations of air warfare dynamics available in war games of this scope. This article addresses the primary factors influencing the planning of an air campaign, along with an examination of the role and uses of air power. As the optional air rules are exemplary, it is assumed that players are using the optional air rules package.

Air power is an offensive weapon. Aircraft take the war to the enemy, whether striking far behind the battle lines or in direct support of ground troops. No army can realistically hope to be victorious when massed enemy aircraft can strike anywhere and everywhere without warning. Since air power is so potentially decisive, it is necessary for players to use their air forces for maximum advantage. This involves careful thought and planning, as there are many nuances involved in fighting an air war.

Command of the Air

Planning to fight the air war involves the goal of air superiority. Simply put, this means being able to hit your opponent with little interference, while your opponent has great trouble hitting back. Winning air superiority is needed to bring the full power of your air force to bear against the enemy. Certainly it is easy to visualize that with no fighter aircraft, and bases rendered unusable, the enemy is at the mercy of your air force. Of course, if you lose the battle for air superiority, then you are at the mercy of your opponent's air force. Therefore, you must take steps to assure that the air battle is won. This means that all other air operations, notably ground support, are secondary in priority.

To confuse the issue, there are gradients of air superiority. Sometimes one has only limited air superiority over a certain sector of a battle. Air superiority can be as small as that, or as large as the entire theater. In game terms, local air superiority may be defined as being able to conduct bombing attacks in a given spot on the map, on a given turn, without enemy interference--in other words, outside the interception range of enemy aircraft. Total air superiority means being able to strike anywhere on the map, any time, with only token threats of enemy interception attempts.

In his superb book The Air Campaign, Colonel John Warden writes of the complex nature of waging a battle for air superiority:

Attaining air superiority is not simple in either concept or execution. To begin the process, one must know that there can be a variety of circumstances under which the air battle is joined, and one must understand one's own position before engaging. Otherwise, it is possible to fight a battle well planned for the wrong circumstances. And fighting in the wrong way at the wrong time could well be disastrous.

It is highly recommended that players closely examine the strength and disposition of friendly and enemy air forces before play begins. Air forces are so flexible and adaptable to circumstances that it is all too tempting to just start the game, see what happens, and bomb a few ground units. The stakes are very high, though, as the side that loses air superiority will be in deep trouble. Furthermore, if the starting forces are relatively equal, then the battle for air superiority may last all game. So it is important to be aware of what factors influence the air war. As in ground warfare, a center of gravity is a useful concept to aid planning. In the struggle for air superiority, air bases and fighter aircraft are primary centers of gravity.

Examining air base location and quality is essential to understanding how the air war will be fought. How many bases do you have? Are any close (within 5 hexes--the interception range of fighters) to the front lines? Are there any level 2 or 3 bases? Are your bases mutually supporting (within 5 hexes of each other) or isolated? Do you have any off-map air bases? Ask the same questions when examining your opponent's air bases.

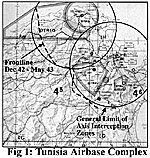

If you have only a few bases, all level 1 and located far from the front, you will have a tough time striking your enemy with mass and concentration. Having air bases located close to the front and mutually supporting is, on the other had, a significant defensive advantage. Such an air base complex can have a dominating effect on the campaign. For example, the front line in the northern part of the theater in Tunisia, from the coast to Medjez el Bab, remained stabilized for nearly six months, partly due to logistics, but also because the front line ran so close to major Axis airfields (see figure 1).

If you have only a few bases, all level 1 and located far from the front, you will have a tough time striking your enemy with mass and concentration. Having air bases located close to the front and mutually supporting is, on the other had, a significant defensive advantage. Such an air base complex can have a dominating effect on the campaign. For example, the front line in the northern part of the theater in Tunisia, from the coast to Medjez el Bab, remained stabilized for nearly six months, partly due to logistics, but also because the front line ran so close to major Axis airfields (see figure 1).

Active fighter units on these bases keep interception options open and ensure that an attack on any one base will lie within the interception zone of another, thus halving Allied bombing attacks due to DG effects. [Ed note: OCS Opt.6e]

For offensive operations, you will want to have some level 2 or 3 air bases available. These are important because the activation of air units depends on air base level. High-level bases allow for stacks of aircraft to fly together, land, and refit in the next turn. Also, they can hold more aircraft; even though you cannot move more than three air units in a stack, having a couple extra units at the base increases flexibility and keeps your opponent guessing. Off-map bases are useful and safe, and they can increase options and flexibility. In the Tunisian theater, off-map bases make is possible to flank enemy air defenses. This is unfortunate for the Axis, as the Allied aircraft have the range to attack all along the coast of Tunisia, thus tying down German and Italian fighters.

Since air units must move in a straight line from base to target, the position of bases is significant. Fighters can be placed on station (also known as combat air patrol or CAP) to block a threat axis. An alternate air base may offer an axis that your opponent cannot afford to cover with other fighter units. Sometimes, building a new air base will help the air war by giving you a new axis or by supporting an isolated base. Repair or upgrade important air bases if possible, especially if you are on the offensive. Remember that ground forces can greatly aid the air war by capturing enemy air bases.

Though the fighter unit is best employed attacking airborne targets, don't be lulled into thinking that the best way to destroy enemy aircraft is in the air. Air-to-air combat is essentially attrition warfare, especially if the opposing air forces are fairly equal. The best way to destroy other aircraft is on the ground, where they are totally helpless. Therefore, the battle for air superiority is best fought over your opponent's air bases. Seek to target enemy air bases at every available opportunity. It is not easy to destroy an air force on the ground, as level 1 air bases cannot be further reduced and one air unit at each base can be declared protected from an air base attack.

Thus, a dispersed air force on level 1 bases does not present you with useful targets. Attack level 2 or 3 air bases or those level 1 bases with two or more inactive air units. This is striking at the heart of your opponent's center of gravity. Of course, the comments above assume your bombers and (hopefully) fighters can reach important enemy air bases. If your aircraft cannot reach your opponent, but your opponent can reach your bases, you are immediately cast into a defensive posture. In this case, you must strive to inflict enough losses (not just Abort results) on your opponent to make him abandon any notion of air offensive.

You will want to have fighters with high ratings and lots of them in your battle for air superiority. Fighter aircraft are a major center of gravity. Do your fighters match up in terms of numbers of units and air-to-air ratings? If yours are superior in both categories you are in luck. In any case, the best way to use fighters in the air superiority battle is to use concentration and mass to stack the odds in your favor. Fighting with superior numbers gives you advantage points [Ed. note: OCS 14.10] and these increase the odds of causing losses in enemy air units, as opposed to mere aborts. Engage enemy fighters only when you have equal or superior numbers of fighter units in a particular air combat.

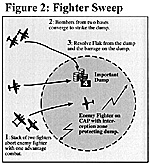

One of the best uses of fighter units is in the fighter sweep. One or more fighter units move as a stack to engage enemy aircraft on station, usually enemy fighter CAPs. This tactic also requires your stack to fly from the same base, so if you have a three-unit stack, it is best to have a level 2 or 3 air base to refit those fighters quickly. Use a fighter sweep to knock a hole in your opponent's air umbrella and then pour a big stack of bombers through to strike an important air base or other high-value target (see figure 2).

One of the best uses of fighter units is in the fighter sweep. One or more fighter units move as a stack to engage enemy aircraft on station, usually enemy fighter CAPs. This tactic also requires your stack to fly from the same base, so if you have a three-unit stack, it is best to have a level 2 or 3 air base to refit those fighters quickly. Use a fighter sweep to knock a hole in your opponent's air umbrella and then pour a big stack of bombers through to strike an important air base or other high-value target (see figure 2).

As you never have enough air units, this represents a major effort, so make the best of it.

CAP is a useful mission for fighters, but not an ideal one. It surrenders initiative to the enemy and can be expensive in terms of fighters units. If you put one fighter unit on station, you are vulnerable to a sweep. Using two- to three- fighter CAP stacks makes a sweep less likely, but is very expensive, so to be successful, place a CAP stack directly on an important threat axis, or on an important target hex. Only one interception can take place per ten-hex radius [Ed note: OCS Opt.6f], making a stack of CAP most useful if the opponent enters the hex containing the stack. [Ed note: see OCS 14.8c and Opt6.g.] The best use of CAP is a fighter unit active at an air base.

From there, you can choose to intercept or land and be protected if an enemy strike approaches. If you opponent does not attack, your unit is still active and ready for a mission on your next turn. Usually, though, you will find a need for CAP more than five hexes from an air base. As you cannot defend everything, use CAP to protect important targets or sectors of the battlefront. An aggressive variant of CAP is to enter station within five hexes of an enemy airfield with inactive fighters. When they refit, the enemy fighters will be DG. Needless to say, this tactic works best against isolated air bases; otherwise your fighters will also become DG.

The way to fight with air power is to keep pressure on the enemy and keep him guessing. On any given turn, one side or the other may claim air superiority over a portion of the battlefield. Being committed to winning air superiority does not necessarily mean sending every available aircraft after enemy air bases in one great effort. Unless your opponent habitually places big stacks of inactive air units on unguarded bases, the air war will be a cagey game of give and take.

Timing and deception are very important. When your opponent moves his fighters to a spot over the battlefield, strike his air bases. When he covers his air bases, strike over the battlefield. Look for openings and weaknesses. Seek to inflict losses in his air units by fighting with superior numbers. Be very aware that in every game turn there are three phases in which aircraft can move, but they can move only once until refitted in the owning player's turn. You do not want to be too predictable nor do you want to use all your air power in one phase, only to give your enemy a chance to undertake air operations unopposed. Remember that unlike ground operations, where one can see the front line and any concentration of units, air forces are flexible because they can concentrate so quickly one turn and then hit completely different targets next turn.

Maximize your air power by striking important targets. Air power, because it can strike almost anywhere, has great shock potential. Strike with mass and concentration, seek to unbalance and confuse your opponent. Hitting your opponent's air bases is a good way to get him off balance and thinking defensively.

Shaping the Battlefield

Yet there are other centers of gravity available. Again, before play begins, look at other targets for your air force to strike. These include ports and supply dumps, interdiction, and ground support. Sometimes centers of gravity can be identified, but are not easy to take down.

In Tunisia, the mothers of all centers of gravity--Axis ports--are not at all easy to take out, unless of course the Luftwaffe obligingly decides not to defend them. In that case, the Allies can bomb the ports to oblivion and every Axis ground unit will quickly starve. Supply is essential for ground armies to fight and move. Striking dumps is hitting your opponent at a center of gravity. Realize, however, that an effort against your opponent's supply dumps and sources will not give you instant and dramatic results. Patience is required, as is persistence. [Ed note: see the fourth paragraph of Boyd Schorzman's letter in Ops 21] Also, terrain modifiers and dispersion of dumps adversely affect what damage you can do against your opponent's supply points. As the presence of enemy fighters can DG your aircraft before bombing, you would like to have air superiority before you can hope to obtain serious results.

Timing plays a role in an effort against enemy supply. If you are building up for a ground offensive, striking enemy supply will lower his ability to sustain a defensive effort. By the same token, an opponent's attack will fizzle if he runs out of supply. Thus, choosing to attack an opponent's supply is best in conditions of air superiority, when the enemy is expecting heavy ground fighting and movement, and when you have at least a couple turns to attack dumps.

Striking railways also slows the flow of units and supplies to the front, as does bombing ports. Usually the port is the higher value target, if both are available. As with targeting supply dumps, this is best done with persistence and air superiority.

Interdicting the movement of ground forces can sometimes have a great effect on the course of a ground battle. Interdiction needs at least air superiority over a given segment of the battlefield to be successful. [Ed note: compare OCS rules section 14.15 and Opt.6j regarding interdiction and serious interdiction, and note especially the different effects on supply draw and throw]

It is best to make a big effort: interdicting several key road junctures throws off your opponent's plans of maneuver, restricts the movement of reserves, retards an opponent's breakthrough, jams up withdrawing enemy forces, and slows your opponent in general. Battlefield interdiction is productive when your opponent is under great demands to move. With the proper timing, even one turn of air superiority over the battlefield can allow interdiction to strongly influence the battle on the ground.

Close Air Support

As ground support can be flown somewhere on the front almost every turn, it is very important to decide, before the game begins, how much effort you are willing to spend on ground support. It is too easy to get caught up in hitting ground targets just because they are readily available. Air assets are best used on important centers of gravity; their range and ability to instantly strike anywhere within that range mean that, unopposed, they have a wide selection of targets. If you decide to use air units for close air support, strike at important targets. Air units will have the greatest effect when bombing enemy ground units in open terrain, in move mode [Ed note: OCS Opt.2d], adjacent to a friendly ground unit. Local air superiority is a must, else all bombing values are halved. As always, timing is important. If your forces are attacking and have nearly achieved a breakthrough, that is a great time to call down some air strikes to soften up that last line of defense. On the other hand, if your opponent is pouring troops through a breach in your defense, air strikes might well assist counterattacking forces.

In the preparation of a set offensive, air strikes can weaken enemy defenses by targeting artillery, antitank units, and reserves. These are not usually easy targets, however, as they will be behind the main defenses and will benefit from being unspotted by adjacent ground troops.

If your air force is capable of conducting Hip Shoots, you have a powerful option for using aircraft against ground units. Hip-shooting aircraft can attack during any of your movement phases, and your air force can strike a target more than once. Hip Shoots are great in a fluid situation, especially as a prelude to friendly overruns. This sort of attack, an attack on the move with air support, is what made the blitzkrieg so potent. You can use Hip Shoots in one great pulse of bombing power, or send wave after wave of aircraft after an enemy position. The Germans with their Stuka dive bombers preferred the first style, the Allies with their plentiful fighter-bombers, the latter.

Planning and Flexibility

The air campaign is a vital, but not easy to plan, aspect of an OCS game. An air campaign requires a player to examine forces before the game, then think about how much effort will be expended to gain air superiority, bomb ports, railroads and supply dumps, and interdict a strike at ground troops. An air campaign requires great flexibility, as a step loss or two can change the nature of the air battle. One important aspect of the air war, which is again best decided before play begins, is knowing when to stop a given course of action. Your air force will take losses.

Before the game starts, think about what you want to accomplish and what casualties you can afford. Generally, it takes only a few key losses to take out much of your striking power. Air units are brittle. Rebuild them when possible, especially fighters if the air war is close.

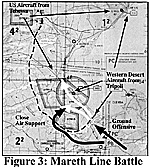

A classic, textbook example of an air superiority campaign comes out of the Tunisian theater: the battle of the Mareth line (figure 3).

Before the game starts, think about what you want to accomplish and what casualties you can afford. Generally, it takes only a few key losses to take out much of your striking power. Air units are brittle. Rebuild them when possible, especially fighters if the air war is close.

A classic, textbook example of an air superiority campaign comes out of the Tunisian theater: the battle of the Mareth line (figure 3).

Three weeks before the British 8th Army began its offensive against the Axis position, the Allies made a vigorous and sustained attempt at air superiority. The Germans and Italians were hampered by having only a few isolated air bases to work from, and these received constant attention from Allied bombers. In addition, the Allies flew missions against the front lines, supply dumps, and ports. The Americans attacked from the west, the Desert Air Force from the east.

The Axis fought hard and both sides lost many aircraft in swirling battles between the clouds. A few times, Allied bombers caught Axis aircraft on the ground, destroying several. By the end of March, the Axis aircraft were fighting for the survival of their bases, leaving the troops at the front line unprotected. Then the ground offensive started. The attack got bogged down in the coastal fortifications. General Montgomery switched his attack with his famous "left hook" through the desert. But there too, the British had to break through a narrow pass, defended with antitank guns. At this point--contrary to all RAF pre-war doctrine--every available British fighter-bomber flew waves of close air support missions to take out the German antitank guns. Flak took a toll, but the breakout was achieved and 30th Corps rushed through the breach. The Afrika Korps, outflanked and nearly cut off, barely escaped annihilation.

In the battle for Tunisia, the British, American, Italian, and German air forces fought hard for six months to dominate the air. At the end of the campaign, the Allies had used their air superiority to starve the Axis out of Africa. In fighting a gallant but losing battle, the Luftwaffe lost some 2,500 aircraft. It was a defeat as great as the loss of the entire Army Group Africa.

Of course, not all air forces will have the proper inventory of aircraft types to attempt such an air superiority campaign. The Allies were greatly helped by the Axis decision to fight the decisive battle in Tunisia from an exposed and outflanked position. On the Russian front, both the Germans and the Soviets have essentially tactical air forces, designed to strike the front lines in support of ground troops. Yet even here, force concentration, deception, timing, and a focus on air superiority will help one side to maximize its air units.

Final Words

Know your priorities and centers of gravity before play begins. Decide how much effort you will give to air superiority, supply dump attack, and ground support. Be patient and persistent. If your air force is inferior, you are on the defensive. In all cases you must fight with mass and concentration. In the words of the Luftwaffe's Adloph Galland, "One of the guiding principles of fighting with an air force is the assembling of weight, by numbers, of a numerical concentration at decisive spots."

[Ed note: Readers of "Running an OCS Air Campaign" from last issue will notice that Lee touches on similar points, including a high regard for Warden's book, the importance of air superiority, and the need for focused, sustained effort rather than uncoordinated, opportunistic air missions. Though this article follows through with several of the ideas Dean expressed, Lee wrote and submitted it before he had any chance to look at Dean's.]

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #23

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com