Perhaps the most critical skill battlefield commanders learn is how to read a map. The commander and staff use the map to figure out where they are, assess the battlefield situation, and plot their deviant behavior. At lower echelons, a crucial part of reading the map includes an understanding of the 'Line of Sight' (hereafter referred to as LOS). A commander must use LOS to make such decisions as which hilltops are key terrain, which avenues of approach will hide the unit from enemy sight, and where to post forward observers. The contour map is ideally suited for these purposes. Unfortunately, the average wargamer does not receive formal training in reading a contour map. Here is a crash course.

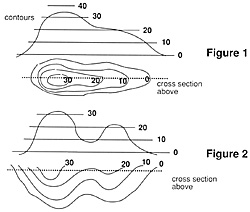

First, one must understand how contour lines work. A contour line marks the series of points that lie at a certain elevation. To show how this works, take a bowl and turn it upside down on a table. Wrap a rubber band around it such that the rubber band is the same distance from the table all the way around the bowl. Do this with several rubber bands and look straight down at the bowl with one eye. The image is that of a 2-D contour map. Obviously, you can do a-Lis with any shape. Figure 1 illustrates a shape just as you might see it on a map. Note that the terrain slopes smoothly and continuously between contours. Many people mistakenly view the contour map as a series of plateaus. Later examples will illustrate how the layer-cake heuristic' may be misleading.

First, one must understand how contour lines work. A contour line marks the series of points that lie at a certain elevation. To show how this works, take a bowl and turn it upside down on a table. Wrap a rubber band around it such that the rubber band is the same distance from the table all the way around the bowl. Do this with several rubber bands and look straight down at the bowl with one eye. The image is that of a 2-D contour map. Obviously, you can do a-Lis with any shape. Figure 1 illustrates a shape just as you might see it on a map. Note that the terrain slopes smoothly and continuously between contours. Many people mistakenly view the contour map as a series of plateaus. Later examples will illustrate how the layer-cake heuristic' may be misleading.

Most wargamers can draw a contour picture given the piece of terrain but reading a map requires the gamer to conceptualize that terrain given the picture. Conceptualizing is easy when one recognizes the patterns that contours take on. The simplest pattern to understand is the spacing between lines. As contour lines get closer, the slope gets steeper. The hill mass in figure I shows this as well. As a limit, contour lines on top of each other represent a vertical dropa cliff. Alternatively, lines that are very far apart would represent a plain.

It is rare, however, that contours will be the same distance apart and the slope constant. To arrive at the correct picture, just put the different slopes together. If the contours are far apart at the higher elevation and closer at the lower elevation, the shape is convex. If the contours are close at the higher elevation and far apart at the lower elevation, the shape is concave. An example of concavity would be the left side of figure 1, while convexity would be on the right. By piecing the slopes together like this, one can picture any undulation of the land (see figure 2).

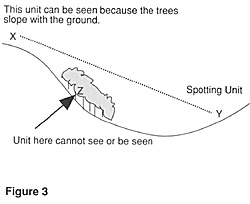

Not only contours affect the LOS between two points. Obstacles to LOS also include buildings, woods, and other features that break the landscape. Here, the 'layer-cake' approach is a little more appropriate. At the edge of the obstacle, the elevation instantly changes to that of the next higher contour level. However, one must remember that as the ground underneath the obstacle slopes, so does the elevation of the obstacle (see figure 3). For LOS purposes, it is also important to note that the unit is at ground level and not at the highest level of the obstacle.

Not only contours affect the LOS between two points. Obstacles to LOS also include buildings, woods, and other features that break the landscape. Here, the 'layer-cake' approach is a little more appropriate. At the edge of the obstacle, the elevation instantly changes to that of the next higher contour level. However, one must remember that as the ground underneath the obstacle slopes, so does the elevation of the obstacle (see figure 3). For LOS purposes, it is also important to note that the unit is at ground level and not at the highest level of the obstacle.

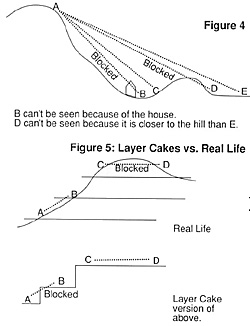

Wargame commanders have yet another hurdle in reading a map than their real life counterparts. In real life, the commander finds out for better or for worse when the action starts while wargamers must agree on the lay of the land to determine LOS. Players rarely dispute LOS when both endpoints are at the same level. Either the obstacle is there or it isn't. Problems most often arise when one of the endpoints may be in a blind spot created by an obstacle or the changing slope of the land. Blind spots occur when the slope close to the lower endpoint is steep relative to the slope close to the higher endpoint. Fig. I provides an excellent example of the slope concept. A unit at the foot of the hill on the left side would be in a blind spot since the hill gets very steep there when compared to a unit at the top of the hill. Obstacles such as trees and buildings have a vertical slope on the opposite side and will often provide a blind spot. As fig. 4 illustrates, the closer the potential obstacle is to the lower point and the higher it rises above the lower point the more likely the chance that the unit is in a blind spot.

People using the layer-cake heuristic will have trouble figuring out blind spots because the heuristic eliminates the role of slope in determining LOS. If one uses plateaus to conceptualize the terrain they will be able to understand the general shape of an area but not the delicacies of the slopes. As shown in figure 5, LOS that normally exists for a concave slope will often be blocked using the plateau approach. Often, players using plateaus also forget that the highest elevation (e.g.: hilltops or ridgelines) has some curvature that may block LOS (also shown *in figure 5). The ability to recognize the actual lay of the land will not only add to the realism of play but also the ability to play well.

People using the layer-cake heuristic will have trouble figuring out blind spots because the heuristic eliminates the role of slope in determining LOS. If one uses plateaus to conceptualize the terrain they will be able to understand the general shape of an area but not the delicacies of the slopes. As shown in figure 5, LOS that normally exists for a concave slope will often be blocked using the plateau approach. Often, players using plateaus also forget that the highest elevation (e.g.: hilltops or ridgelines) has some curvature that may block LOS (also shown *in figure 5). The ability to recognize the actual lay of the land will not only add to the realism of play but also the ability to play well.

Of course human perception is a creative thing and even two players with an excellent grasp of map reading will sometimes disagree about the existence of a LOS. Therefore, games that include the use of LOS must have some rule to resolve disputes. The third edition of the TCS rules will settle the problem by comparing the relative slopes between firer-obstacle and firer-target with the person claiming no LOS choosing the hex that he thinks blocks the LOS. Players who can visualize the terrain will have a distinct advantage over their opponents. They will be less likely to waste shots or run into those surprise LOSs that can ruin an operation. For those just learning to read a contour map, it may be helpful to try drawing some LOSs using the ideas in this article. Use a contour map to find some sample LOSs and draw the cross-sections of them. If you have time before a game, this is a great way to plan a defense and see what you can and can't cover. After a while, the pictures will no longer be necessary and by just looking at the map you will be able to see the shape of the terrain.

Back to Table of Contents -- Operations #10

Back to Operations List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1993 by The Gamers.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com