What I’ve always found the most fascinating thing about the Duke of Marlborough was neither his tactical skill-—even though he was never defeated—-nor his strategic skill—-which was prodigious. Not even his political skill in maintaining a polyglot alliance in the face of the awesome power of the Sun King, Louis XIV of France.

What I’ve always found the most fascinating thing about the Duke of Marlborough was neither his tactical skill-—even though he was never defeated—-nor his strategic skill—-which was prodigious. Not even his political skill in maintaining a polyglot alliance in the face of the awesome power of the Sun King, Louis XIV of France.

Artillery during the War of the Spanish Succession was not the mobile force we are used to seeing Napoleon deploy and maneuver. Instead, it is remarkably immobile.

What I find the most fascinating is that a future relative of John Churchill, the First Duke of Marlborough, while unemployed in the period between World Wars I & II, sat down and made an exhaustive study of his illustrious ancestor. That man, Sir Winston Spencer Churchill, wrote a history of the War of the Spanish Succession, and made a study of the diplomatic skills that were necessary to maintain an international alliance against a great continental power. Churchill’s writing of the life of his own ancestor, Marlborough, was his tutelage for his job as Prime Minister of England and the leader of the Free World against the Axis Alliance of Japanese Imperialism, Italian Fascism and German Nazism. Since Churchill’s efforts went far to save the Free World into which we were all born, I would cite that as the most lasting of the great Marlborough’s contributions.

Europe had spent much gold and spilled much blood to maintain the balance of power. They had agreed that upon the death of King Charles II of Spain—who had no direct heir—that all of the Spanish possessions would be divided, so as to maintain the balance of power in Europe. Charles, however, upon his deathbed drew up his own will, and offered it ALL to the French Duke of Anjou. Louis XIV had him accept. Suddenly, France was the power of the universe. ‘There are no more Pyrenees,’ said the French ambassador.

Europe had spent much gold and spilled much blood to maintain the balance of power. They had agreed that upon the death of King Charles II of Spain—who had no direct heir—that all of the Spanish possessions would be divided, so as to maintain the balance of power in Europe. Charles, however, upon his deathbed drew up his own will, and offered it ALL to the French Duke of Anjou. Louis XIV had him accept. Suddenly, France was the power of the universe. ‘There are no more Pyrenees,’ said the French ambassador.

French troops marched into the fortresses of the Spanish Netherlands, which had been the primary defense of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. Holland, which was led by its Stadholder, William III, opted for war. William was also King of England, and so the two ventured into the breach once more against the continental aggression of the Sun King. The Hapsburg Empire and a host of lesser states joined. The die was cast. And yet, before anything could be accomplished, William III died. Such was the situation that Marlborough inherited.

The Dutch Deputies were reluctant to permit Marlborough from seeking or accepting battle with the French—in fact they prohibited it. Hence, in the early phase of the War of the Spanish Succession there were marches and counter marches, there were sieges and cities taken, but every opportunity to crush the armies of the Sun King were cast aside by the cautious Dutch. The Bavarians now joined the French, and the French sent them an army to help capture Vienna and crush the Hapsburg Empire.

In 1704 Marlborough got permission from the Dutch to campaign in the Moselle River valley. He and his British, and those troops in British pay marched south, down the Rhine to the Moselle, but they did not march up the valley of the Moselle. Instead, they crossed the Rhine on a bridge of boats that had been constructed for them in advance, and marched eastward, off into Germany. On their march the Prussians and various German contingents joined them. Finally, Prince Louis of Baden joined Marlborough with the Imperial Army of the Upper Rhine. Prince Eugene also joined Marlborough. He brought with him no troops, but he did bring that same spirit to seek battle and crush their enemies. Deeper into Germany they marched, until they reached the Danube River at Ulm, in the middle of what is now southern Germany.

In 1704 Marlborough got permission from the Dutch to campaign in the Moselle River valley. He and his British, and those troops in British pay marched south, down the Rhine to the Moselle, but they did not march up the valley of the Moselle. Instead, they crossed the Rhine on a bridge of boats that had been constructed for them in advance, and marched eastward, off into Germany. On their march the Prussians and various German contingents joined them. Finally, Prince Louis of Baden joined Marlborough with the Imperial Army of the Upper Rhine. Prince Eugene also joined Marlborough. He brought with him no troops, but he did bring that same spirit to seek battle and crush their enemies. Deeper into Germany they marched, until they reached the Danube River at Ulm, in the middle of what is now southern Germany.

At Donauworth, on a fortified hill overlooking the Danube crossing, the enemy stood entrenched. Marlborough attacked directly from line-of-march. The British grenadiers marched straight up the hill. Not only had the Franco-Bavarians erected a wall of earth to protect them, but also they dug a wide, deep ditch in front of them to forestall any English attack. Each tall British grenadier carried a faggot in his arms—that is to say, a bundle of sticks—and threw said faggots into the ditch and marched over them (taken in modern terms, such a statement might appear to be inappropriate).

To stop the onslaught, the French massed many ranks deep, so as to maintain a continuous fire. Of course, this meant that they could not guard the entire perimeter of their defenses. As the rest of the column came up they flowed over the undefended works and took the enemy in the rear. The victory was complete.

In this relatively small action Marlborough displayed the tactical system, which was his genius. He took his best troops and thrust hard at a point in the enemy’s lines that the enemy could not let fall. The enemy reinforced that point with his last reserves. (It has been said that once a battle has begun, the only thing a general can do is to commit his reserves, and that he who has the last reserve to commit will win.) Without reserves, and with a weakened line, the enemy line could be breached. Marlborough did just that at Donauworth, and would repeat that recipe in his four great battles.

Marlborough demanded Bavaria’s surrender. Bavaria refused, so his forces ravished the country. (Ravishing was always a favorite part of every soldier’s duties.) The French sent another army to join the Franco-Bavarians and finish the work.

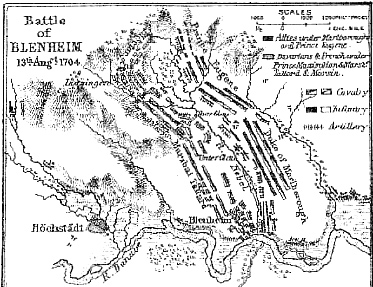

Marlborough sent the reluctant Prince of Baden to besiege Ingolstadt, and with Eugene, they decided to attack the Franco-Bavarian Army. Marlborough and Eugene were outnumbered 56,000 to 52,000. The Franco-Bavarians also had a considerable advantage in artillery of 90 to 66. The marshy banks of the Nebel, which the Franco-Bavarians defended, offered them a considerable advantage. Wooded heights protected the enemy’s left, and the mighty Danube protected their left. There was nothing for it both for Marlborough and Eugene to attack frontally across the Nebel against a superior foe. (But our heroes were valiant and offensive, their hearts were pure, and if you’ve read the history, you already know they won.)

Marshal Marsin’s French and the Elector of Bavaria’s troops defended the Nebel from the fortified town of Oberglau northwards with 42 battalions of infantry and 67 squadrons of cavalry. The French Marshal Tallard defended the Nebel from there to the Danube at the fortified village of Blenheim with 36 battalions of infantry and 76 squadrons of cavalry. Prince Eugene on the Allied right attacked Marsin and the Elector, while Marlborough, controlling the left and center, attacked Tallard with his 38 battalions of infantry and 86 squadrons of cavalry.

Marshal Marsin’s French and the Elector of Bavaria’s troops defended the Nebel from the fortified town of Oberglau northwards with 42 battalions of infantry and 67 squadrons of cavalry. The French Marshal Tallard defended the Nebel from there to the Danube at the fortified village of Blenheim with 36 battalions of infantry and 76 squadrons of cavalry. Prince Eugene on the Allied right attacked Marsin and the Elector, while Marlborough, controlling the left and center, attacked Tallard with his 38 battalions of infantry and 86 squadrons of cavalry.

It really resolved almost as two separate battles. Eugene pushed forward over the Nebel with 28 battalions of infantry and 92 squadrons of cavalry. He drove them back through the wooded hills on the Franco-Bavarian left. By applying constant pressure, the outnumbered Eugene kept Marsin and the Elector from assisting Tallard when he got into trouble.

On the far left, Marlborough thrust 20 battalions under the command of Lord Cutts (nicknamed the Salamander because of the number of times he found himself in the hottest spots) against the Bavarian village of Blenheim. The British were conspicuous in their bright red coats. The infantry were supported in their attack by 14 squadrons of cavalry. Tallard kept sending more and more of his infantry to hold Blenheim, denuding his center of infantry. At that point, Marlborough simply marched across the Nebel. His cavalry drove off the outnumbered French cavalry, and his infantry crushed the vastly outnumbered French infantry. The large number of French infantry in Blenheim surrendered, while Marsin and the Elector beat a hasty retreat. The victory was complete. The Hapsburg Empire and Vienna were saved, and Bavaria was defeated.

Duke of Marlborough: Ramilles and Beyond

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet Spring 2003 Table of Contents

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Novag

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com