When your army meets their army, there are essentially seven classical maneuvers by which you may seek to triumph. Alas, it is all too often that one sees two armies of miniatures wade into each other like a junior high playground brawl. The fact that there is no plan and no coordination of the various parts reveals that there is no generalship. Bring generalship to your battlefield and get results.

When your army meets their army, there are essentially seven classical maneuvers by which you may seek to triumph. Alas, it is all too often that one sees two armies of miniatures wade into each other like a junior high playground brawl. The fact that there is no plan and no coordination of the various parts reveals that there is no generalship. Bring generalship to your battlefield and get results.

The Anglo-Saxon Fyrd prepares to receive a wedgie of Vikings.

1. Penetrating the Center

When the enemy has a continuous or extensive front, he has spread thin. Mass your forces in the center and breakthrough. You can add subtlety to this maneuver by holding out a reserve, and using it to rupture the enemy’s line when your own front line troops have worn him down. When you break his center, his battle line is broken, and his cohesion sundered. Using your central position, you may drive the two parts of the enemy’s forces further away from each other, and turn upon one portion and crush it. You may also exploit your breakthrough and drive forward against his communications, or whatever his army was trying to defend by making a stand at that point.

Smoke is rising from scattered homesteads. Peasants are fleeing, driving their livestock inland. The Vikings have come.

-

The Anglo-Saxon Fyrd has gathered to form a line of battle. As the Vikings arrive, they form a dark, massive wedge, and move forward. Crazed Berserkers, half-naked fanatics, form the point of the wedge. The wedge moves forward. Bondi archers fire upon the solid Anglo-Saxon shield wall, which stands to receive their fire. The Vikings break into a charge. Their battle cry breaks like thunder. Javelins and throwing axes strike home among the ranks. With a crash, the Viking wedge violently hits the line. Men fall on both sides, but from the depth of the wedge Viking warriors continue to spew forth into the fray. The Anglo-Saxon center thins. The wounded and the frightened head for the rear and safety. Panic sets in, and the line breaks.

In an Abbey on a nearby hill, the monks prey, “Oh Lord, deliver us from the fury of the Norsemen.”

Having your center penetrated can ruin your entire day. The Duke of Marlborough won 3 of his 4 great battles by penetrating the French center. In 1940, the Germans penetrated the French center at Sedan, and proceeded to turn upon and crush the Allied left wing. (Do you think the French enjoy having their center penetrated, or do you think they were just inept?) Of course, this maneuver can fail dramatically if the enemy has reserves and commits them to contain your breakthrough, as was the case at the World War I battles of Cambrai and the Somme.

2. Enveloping a Flank

2. Enveloping a Flank

Men in the line of battle many ranks deep feel secure. They have someone in front of them, someone behind them, and someone to their right and their left. Friends surround them.

The last man on the army’s flank, however, feels insecure. His friends do not surround him. There’s nobody to protect his open flank. The fact that the enemy can surround him preys upon his mind, and weakens his resolve.

Once the development of the chariot, and later cavalry, gave mobility to armies, it became possible to take advantage of the inherent vulnerability of the enemy’s flanks. A mobile reserve could be held out of the line of battle until the enemy’s forces were committed. Then they could sweep around one of the enemy’s flanks, and roll up his line as if it were an old rug.

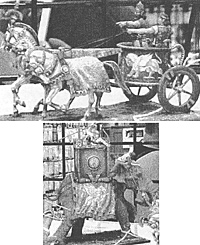

- Like a solid wall of ebony, the Sudanese army stands in defense of its homeland, one flank anchored upon the banks of the Nile. The Egyptian host approaches, and the archers exchange arrows. The distance narrows still greater, and javelins fly. Presently, the sound of clashing shields and the metallic clang of ax and sword is heard. The battle rages beneath the burning sun.

With a signal, our reserve of chariots begins to move forward. They swing left, to where the Sudanese flank hangs suspended in the endless desert. As the Egyptian chariots swing wide around the Sudanese flank, they can see the ebony warriors casting nervous glances at the chariots. By the time they decide to bolt, there is nowhere to go. Egyptian chariots are streaming along their rear, firing a deadly hail of arrows from the chariots into their unshielded backs. The end of the Sudanese line crumbles, while the Egyptian chariots ride on to complete the destruction of the enemy.

Those who break and flee and are caught by the swift charioteers, who ride after them, to leave them face down in the dust, their signature feathered shafts rising from the Sudanese’s backs.

The only difficulty with enveloping the enemy’s flank is that in order to free enough troops to make this effective, you must take them from your line. At Austerlitz, the Austro-Russian Army threw a mean left hook at Napoleon, only to leave themselves woefully under strength on the Pratzen Plateau.

3.Double Envelopment

This is the classic of classic battles of complete annihilation. First developed by the incredible general, Hannibal in 216 BC at the battle of Cannae, the totally outnumbered Hannibal (with 50,000) enveloped both flanks of Varro (80,000), leaving a mere 10,000 to escape. By enveloping and surrounding the enemy army, you gain their surrender or destruction. Von Clausewitz declared this to be the ideal battle. At Kiev in 1941, Kleist & Guderian did it to half a million Russians. Alas, neither Cannae nor Kiev led to eventual victory.

- Consul Varro had tired to shadowing Hannibal as he pillaged Roman soil for his daily bread. Outnumbering the enemy 8—5, he moved out of camp, pinned him against the river, and by doubling the depth of his infantry formations, sought to rupture the invitingly advanced Carthaginian center and shatter his enemy. The attack went in, and the Celts were forced back. On the right flank, the Numidians played their skirmishing games with the Roman horse. On the left flank, the excellent Gallic and Spanish horsemen of the Carthaginian Army crushed the Roman cavalry. The cavalry then swept behind the Roman Army, while the heavy African Infantry on the flanks wheeled inward. The four sides of the box were formed. Varro fled the field and left his army to die.

4. Oblique Attack

The attacker thrusts against one wing of the enemy with great strength, while distracting the enemy’s center and other wing with lesser forces. With any luck, the assailed wing will collapse—-and the enemy army with it-—before the remainder of the enemy’s army can be brought into play.

An Oblique Attack coming in heavy on the right flank.

An Oblique Attack coming in heavy on the right flank.

It’s most notable early success was at the Battle of Leuctra, where the Thebans defeated the Spartans in 371 BC. Epaminondas massed his Sacred Band 50 men deep on his left, and kept the center and right from closing immediately by having his cavalry skirmish with the Spartan cavalry.

For those of you who are fans of the Seven Year’s War, you will realize that this was Frederick the Great’s favorite method of attack. His victory at Leuthen, over a vastly superior Austrian Army, was probably his classic.

5. Feigned Withdrawal

This was the bread and butter method for all steppe peoples. By pretending to flee, you would draw defenders out of a good position and their place in line, only to fall upon their flanks and crush them. It is a grave misfortune that no rules system for ancients/medievals with which we have been acquainted, has this basic tactic incorporated into their rules.

Since only a feckless idiot would voluntarily break his line and abandon good defenses in order to run after a seemingly broken enemy, they do not.

This is a major rules failure of Warrior, DBA, DBM, Might of Arms, and the rest. It’s much like saying that the Vikings can’t get a benefit from forming a shield-wall. Come to think of it, that is another major rules failure. And we won’t even mention wedges.

There may be some of you who say, ‘So what if a few dozen armies aren’t permitted to fight as they did and employ their favorite method of attack? They’re not mainstream European armies!’ Of course, you would be forgetting that mainstream army of the Normans, who used this tactic to triumph at that little known Battle of Hastings! But so much for bad rules.

There may be some of you who say, ‘So what if a few dozen armies aren’t permitted to fight as they did and employ their favorite method of attack? They’re not mainstream European armies!’ Of course, you would be forgetting that mainstream army of the Normans, who used this tactic to triumph at that little known Battle of Hastings! But so much for bad rules.

6. Attack from a Defensive Position

To defend in a good position, and then lunge forward to the attack after your enemy has disordered and exhausted himself, is a time-honored method of waging a battle. The Duke of Wellington springs to mind immediately.

7. Indirect Approach

This attack maneuver is a combination of tactics and strategy. First, the attacker engages his enemy’s attention with part of his force. He takes the remainder of his forces on a long ‘off-board’ march around one of his flanks. This is aimed at interrupting the enemy’s supplies and communications, and forcing him to turn and attack his way out, or perish from an inability to retreat. While Alexander, Hannibal and Caesar all tried this maneuver, it was rarely completely successful, due to the relative immobility of ancient armies.

History has revealed these to be the Seven Classical Maneuvers an attacker can take in order to achieve victory. Next time you’re in charge of the army, instead of saying something like, “Let’s get ‘em!”, try one of these plans instead. Good luck.

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet Spring 2003 Table of Contents

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Novag

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com