Jeff Wiltrout lugged his large, 50-pound tackle-box to my rec room and took out two armies of 15mm figures. He ran us through a DBM game, Roman-versus-unRomans.

Jeff Wiltrout lugged his large, 50-pound tackle-box to my rec room and took out two armies of 15mm figures. He ran us through a DBM game, Roman-versus-unRomans.

The dreaded UnRomans marching into combat.

I have noted (after many, many years of observation and research at the WRG and DBM tournaments which are presented at the HMGS and other conventions) that to join the DBM crowd, you’ve got to have a 50-pound tackle-box in which to carry your armies. You pull out 30 or 40 stands, and announce: “These make up my Macedonian Crustaceans Army.” Then you pull out the next set of figures and announce: “These make up my Thesalonian Wachovian Army.” And so on.

And what’s the difference between the Macedonian Crustaceans and the Thesalonian Wachovians? According to the nitty-gritty, oh-so-accurate army lists set out in the DBM booklets, the Macedonians have 5 more pike stands than the Thesalonians, and the Thesalonians have 2 more cavalry stands than the Macedonians. This is serious stuff.

To my left, commanding the left flank of the Roman forces was Brian Dewitt. I took no notes during the battle, but I think that we had about 50 stands of troops, ranging from Roman heavy infantry (termed ‘blades’) to light troops (termed ‘psiloi’) to cavalry (termed ‘cavalry’).

Brian and I divided the Roman forces between us. I took the cavalry and some infantry on my right flank, while Brian commanded most of the infantry. I think I had about 8 infantry stands and the same number of cavalry. I also had a general, who we shall call Simonius, because he was the big cheese, got an additional pip for himself. The way Jeff explained it, there were two types of generals, each tossing a die:

- A: The first type contributed a die to the entire army. You could assign the die roll to any command within the army. These generals, therefore, were fairly flexible. You could assign pips where you needed them. Our Roman generals were of this first type, and so each turn, when we tossed our two dice, we gave the die with the greater number of pips to the command which needed them most.

B: The second type contributed a die, but only to a specific command. Whatever the result of the dice toss, that particular command was stuck with it.

Jeff indicated that our Roman force ‘cost’ some 325 points, and that, of this total, each general cost around 30 points. Generals were expensive because of the pips each provided. Although early in the battle, I tossed Simonius into combat, risking his very life and limb, and I noted that Jeff kept his own general securely sheltered behind a huge phalanx of pike.

We set up our Roman army in one long line stretched along the table. Our frontage was some 3 feet. Across the field, our opponents were grouped together. Their frontage was about 2 feet across. The opposing unRomans were somewhat more scrunched together than we were because they had a large pike phalanx in the middle of their army. There were about 5 pike columns, each consisting of about 3 or 4 stands, one behind the other. In combat, each pike front stand in contact is worth 3 points, but it gets to add to its value an additional 1 point for every rank of pike behind it. With a column of 3 pike stands, therefore, the combat value of the column totaled 3 for the first stand, plus 2 for the additional 2 ranks, a total of 5 combat points. Our Roman heavy infantry, blades, were worth 5 points each to start with, so it took 3 pike stands to equal 1 Roman heavy infantry.

Jeff explained that a Roman blade stand cost 7 points in the army lists, while a pike stand cost 4 points. In ‘buying’ one’s army, therefore, one had to pay 12 points for the 3-stand pike column, versus only 7 for the Romans, to equalize the combat.

Alas, Wally didn’t realize that no harm could possibly befall a lightly armored man who charges into a bristling wall of long steel pikes on a horse at breakneck speed. Silly Wally. Silly rule.

Alas, Wally didn’t realize that no harm could possibly befall a lightly armored man who charges into a bristling wall of long steel pikes on a horse at breakneck speed. Silly Wally. Silly rule.

Our Roman cavalry were worth 3 combat points, and for several turns they ‘danced’ around the oncoming pike, looking for an opening. At game’s end, Jeff said that my tactics…or lack of them…were incorrect. I should have charged the pike immediately. Even though the combat would have pitted 5 pike points versus 3 cavalry, if I lost, my horses would simply have backed up. While if I won, I would have eliminated the opposing pike column.

In regular DBM combat, each side gets to add its points to a die roll, and if you score higher than your opponent, he backs up. If your total score is double your opponent, he dies. But note that this doesn’t apply to the cavalry-versus-pike combat. All that my cavalry had to do was to simply score higher—not even double the pike score—and POOF! The pike were gone. And even if I lost and the pike’s score doubled that of the cavalry, the cavalry would not have been wiped out. They would have ‘evaded’, and stepped back. A no-lose proposition for the cavalry.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t aware of this titillating bit of DBM combat nitty-gritty, and so my cavalry continued to dance and dance. I thought that in the real world, if cavalry would have charged pike head on, then bad things, very bad things, would have happened to the cavalry. I refer you to the seminal article on the subject, published by the Centre for Provocative Wargaming Analysis, Schticking Der Cavalrie On Der Schpears, by Professor E. Coli. I, of course, am an historical purist, and I didn’t realize that the DBM world differs from our own, and so my cavalry avoided contact and danged.

Another item of note was that when the opposing cavalry won a melee, and our Roman stands stepped back, the opposing cavalry followed up, remaining in contact. Our own cavalry hadn’t taken the graduate level course, Follow Up 101, and so they, when they won a combat, remained in place. The same follow-up procedure applied to the pike stands. They, too, followed up when they won a melee. Our Roman blades, in contrast, when they won, simply stood there, awed at the fact that they had caused the enemy to fall back.

DBM, or course, uses the 6-sided die. Since there’s a finite limit to the results obtained when the die is tossed, the effect of the die must be ‘expanded’ when different situations occur.

An example of this can be seen in the way a couple of Brian’s stands were treated. Brian had amongst his infantry contingent, 2 stands of light troops, psiloi. But these were ‘superior psiloi’, elite psiloi. Ordinary, every day, run-of-the-mill psiloi have a combat value of 2 to add to their die toss. And so did the super psiloi. But the elite stands were entitled to add another +1 to their toss each time they lost a melee.

The effect shows up if we look at the combat results if the psiloi (+2) were up against cavalry (+3). Normally, when comparing modified die tosses, the cavalry would have a chance to double the psiloi, wiping them out, 36% of the time. The super psiloi, since they add a +1 when they lose, give the cavalry a 24% chance to wipe them out. Note, this doesn’t increase the psiloi’s chance of winning. It’s only when they’re losing that their survivability increases.

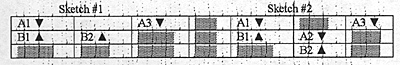

Another interesting DBM ploy concerns the effect of flanking stands. Look at these sketches, in which A’s 3 stands, A1, A2, & A3 face B’s 2 stands, B1 & B2. Assume the combat value of all stands is 3. In sketch #1, the combat between A1 and B1 is even, 3-to-3. The combat between A2 and B2 is not, because of the flanking or overlapping effect of stand A3, B2 is reduced by 1 point to 2, hence the combat is 3-to-2.

Another interesting DBM ploy concerns the effect of flanking stands. Look at these sketches, in which A’s 3 stands, A1, A2, & A3 face B’s 2 stands, B1 & B2. Assume the combat value of all stands is 3. In sketch #1, the combat between A1 and B1 is even, 3-to-3. The combat between A2 and B2 is not, because of the flanking or overlapping effect of stand A3, B2 is reduced by 1 point to 2, hence the combat is 3-to-2.

Assume that A1 and B1 fight to a draw. Their modified die totals are even and they remain in place. And assume, that because of the 3-to-2 combat odds against B2, B2 falls back, and its opponent, A2, follows up.

Now we have Sketch #2. Note that in Sketch #2, A2 is now beside B1. Under the DBM procedures, the presence of A2 acts as a flanking modifier for B1, reducing its value in the combat against A1 by 1 point to 2. And, in the same vein, when A2 faces off with B2, the presence of B1 beside A2, reduces A2 by 1 point.

I have never understood the rationale for this. A stand, sitting beside an opposing stand, yet facing the ‘wrong way’, giving a flank effect.

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet Spring 2003 Table of Contents

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Novag

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com