If I were to be asked which weapon of ancient times is

the most difficult to reproduce on the war game table, I would

unhesitatingly reply--the chariot. Why is this so? Why is it

that I can feel relatively happy about my rules for most types

of troops but am consistently dissatisfied with those for

chariots? The answer, of course, lies principally in the fact

that those of us who have mythical rather than historical set-ups are trying to cram the weapons and tactics of some 3,000

years into one common mold.

If I were to be asked which weapon of ancient times is

the most difficult to reproduce on the war game table, I would

unhesitatingly reply--the chariot. Why is this so? Why is it

that I can feel relatively happy about my rules for most types

of troops but am consistently dissatisfied with those for

chariots? The answer, of course, lies principally in the fact

that those of us who have mythical rather than historical set-ups are trying to cram the weapons and tactics of some 3,000

years into one common mold.

To me, at lest, one of the principal attractions of ancient warfare is the diversity of weapons and types of troops it offers, and for this reason the chariot is not lightly discarded. Yet, it is an historical fact that the chariot was a valuable weapon of war in the early ancient period: pre-Marathon, say and a dead loss afterwards. What caused this somewhat sudden alteration in the status of the chariot? In a nutshell, a disciplined, trained heavy infantry.

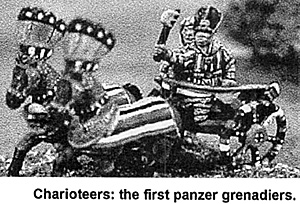

In the heyday of its triumph, the chariot was of two main types, heavy and light. The heavy chariot can be approximated to the heavy tank in the early days of armor. It was relatively slow moving, of heavy construction and was sometimes drawn by Asses rather thaii horses. In both Persia and the West it developed the terrible scythe-blade attached to the wheels. Its use was limited to relatively level ground.

The light chariot was a very different thing and for a very long period formed the backbone of the Egyptian army. Drawn by a pair of horses it carried a driver and an archer, and the main tactic seems to have been a headlong charge at the enemy line behind a stream of arrows. The lack of cohesion of the enemy infantry usually enabled the chariots to break right through them, cutting them up into isolated groups which were easily mopped up by the Egyptians' infantry as it followed up the chariot charge, or dealt with by a second chariot charge, if the chariots were on their own.

The arrival on the battlefield of disciplined and heavily protected Greek infantry who were trained to maneuver as bodies spelled doom for such chariot tactics, especially when backed by an efficient force of missile troops. But in fact the chariot remained an effective force in areas where the ideas of the Greek style had not penetrated-for instance in Gaul and Britain, where until the coming of the Romans, war was a tribal affair and was fought by loose mobs of warriors.

The reasons that we experience difficulty with our chariot rules are two-fold: in the first place we are making general rules to cover the whole period of ancient warfare, rather than specific ones, and the second, we are assuming that all infantry has the resisting power and maneuverability of a Greek phalanx or a Roman cohort. What we therefore need is selectivity. Different rules must be made to cover the effect of chariots on, say, a Greek phalanx, a force of Egyptians, or a mob of Gauls or Celts. Thus, if you are commanding an army whose main striking force is chariots and you come up against a Roman force of equal strength, you will be a fool to fight unless you can achieve an ambush or some such thing.

Your rules cannot hope to achieve a happy medium for all circumstances and this I think is where I have effect in the past. Some of your rules can be general enough-the effect of missile fire for instance. This, I feel, should be relatively ineffective at long range but rarely deadly at short range and the latter should depend on a morale factor, i.e. the ability of the defending missile troops to stand their ground and not panic as the chariots close.

A solid block of disciplined infantry with long spears should be able either to resist the attack of chariots or open lanes for the chariots to pass through. Horses are intelligent animals, and unless maddened, will not dash themselves against a solid object. Anyone who has watched show jumping knows that a horse makes up its own mind as to its ability to pass an obstacle and refuses if it thinks fit. One or two chariots wheeling out of line would soon throw a chariot attack into utter confusion. Thus your rules should make a frontal attack upon steady disciplined troops fairly suicidal, unless the infantry lose their nerve and give way before the charge.

On the other hand, infantry lacking the cohesion of the Greeks or Romans should not be capable of repelling a chariot charge unless either the chariots suffer heavily from missile fire or they themselves lose their nerve. But this should not mean that chariots would inevitably crash through an infantry line and scatter it A chariot is only superior to infantry as long as it keeps going-if it is once bogged down in a press of men, its occupants will be quickly overcome by superior numbers. It seems to me that this should depend on two facts--the depth of the infantry formation and its morale.

I believe that other factors excepted-the chariot would always break through infantry ranked two deep or less. Above this depth, given good infantry morale, there would be a chance of the chariot charge bogging down, and this would increase with each extra rank in depth.

Obviously this situation can be decided in a variety of ways, but here is my suggestion. In a formation of two deep or less, the chariots will cleave straight through, each chariot killing on a frontage of 3 men per rank (assuming this is about the width taken up by a two-horse chariot). Each chariot would dice, and any throwing a #1 would be assumed to have overturned at the moment of impact.

For a deeper formation, the initial impact on the front two ranks would follow the same pattern; but upon reaching the third rank providing that the infantry morale was good (this would follow whatever morale rules you use) there would be by a straight dice throw bent between each chariot and the 3 men facing it. For each additional rank facing the chariot, the infantry would get 50% added to its dice throw. If the chariot won, the line immediately facing it would go down and the process would be repeated with the succeeding line. If the scores tied, the chariot would be halted and an the surrounding infantry would then fight its occupants who would count as two points each to allow for their standing in the chariot somewhat higher than their opponents. If the chariot lost, it would be destroyed.

This rule would make the chariot a formidable weapon against thinly deployed infantry lines, and a worthwhile risk against deeper formations, and would force an opponent faced by chariots to either deploy on a narrower front or take the consequences. At the same time, it must be emphasized that to obtain these results, chariots must be used in mass. Two chariots on their own breaking through a whole infantry regiment is unrealistic--I would suggest that a minimum of one chariot for every four men in the front rank of the infantry being attacked should be necessary to obtain the breakthrough effect.

Obviously there are many points I have not covered in this article, and there may well be faults with the rules I have suggested. I would be most interested in any ideas or suggestions from other members and hope that I may be sparking off some helpful discussion on the subject.

More from Bob & Cleo

First, for those of you who own chariot armies and participate in one of the various ancient/medieval tournaments, you are probably offering up a goat at this very moment so that the gods will favor the early demise-without benefit of clergy-of anyone who would make your army impotent against virtually all comers. Save your goat!

Second, there are a host of ways an historical wargame rules set can avoid this-such as not forcing you to raise your historically mandated basic units when your nation is facing somebody your army never fought. There is also the idea of having a points system that accurately reflects a unit's real worth on the battlefield. The list continues.

Third--I wonder why are there always three good reasons for everything--if chariots are good against the poor quality infantry prior to the Greco-Roman tradition, consider all of the armies of the Dark Ages, and then some. They put their money and training into superior cavalry. Their infantry was often an embarrassment on the field of battle. Use your chariots and embarrass them some more.

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet Summer 2002 Table of Contents

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Novag

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com