Once upon a time, when I was finishing up as an undergrad, I had the good fortune to meet John Curtis, who was then a graduate student at Stony Brook. He had previously been a graduate student at Purdue, in Indiana. There, gaming with THE Fred Vietmeyer, he got hold of Fred’s rules system, Column, Line, & Square.

Once upon a time, when I was finishing up as an undergrad, I had the good fortune to meet John Curtis, who was then a graduate student at Stony Brook. He had previously been a graduate student at Purdue, in Indiana. There, gaming with THE Fred Vietmeyer, he got hold of Fred’s rules system, Column, Line, & Square.

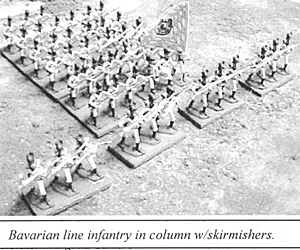

Bavarian line infantry in column w/skirmishers.

He brought them to Long Island, and they’re still playing Column, Line & Square there in several groups to this day. One of the fellows I gamed with, as the 60’s were becoming the 70’s, was a brilliant high school student named Tony Ramienski. That was 30 years ago.

Less than a year ago I was assisting a customer at Borders in my history section, when it became clear to both of us they we may have once met.

“Tony?”

“Bob?”

Well, it seems that both of all of our kids are now college age, and I’ve finished teaching, while he’s finishing army career intent upon taking up teaching. But both of us are packrats, so we thought we still had some CLS mounted 30mm Napoleonics lying around. As it ended up, we had over a thousand points each. At one of our First Friday Games, we did an old Column, Line and Square battle, and Craig Scott came up from Virginia, and mentioned that he also had several thousand points of 30mm CLS Napoleonics, for the next time we played. The game was like childhood revisited. It was a hoot!

CLS has problems, or we’d still be playing it, but I’ll leave the Crash, Lash, & Slash of the rules to Wally Simon in his attached critique. At the time, it was the cutting edge of Napoleonic rules. Unfortunately, the rules were always open to litigation. What I enjoyed was the simultaneous movement. I could usually see what the enemy was likely to do, and hence order my troops to take advantage of what they would do. The alternative in rules is often to sit perfectly still while the enemy army moves in up to you, walks around you, and hits you up-side-the-head, with you helplessly watching him do it. They you trade places. So I guess every system has its shortcomings.

Wonderful! Wonderful! Wonderful!

By Wally SimonBob and Cleo Liebl recently hosted a game employing the old, old Napoleonic standard called COLUMN, LINE AND SQUARE (CLS). Vietmeyer and Bauman authored CLS my copy of the rules has a copyright date of 1973.

The Liebl table measured 6-feet wide by 12 feet long, and it was chockfull of wunnerful, old 30mm figures (Surens and Staddens and Scrubies and SAEs and so on). The battle pitted Austrians versus Bavarians-and-someone-else. Some ten people were at tableside.

CLS focuses on big, big, big units, together with Fred Haub, I co-commanded a small Austrian division on the left flank of the army composed of one battalion of line infantry, one battalion of skirmishers, one gun, and a couple of heavy cavalry squadrons. Our line battalion was composed of 6 stands of 10-men each, a total of 60 men. The stands were some 5 inches in width, so that our battalion’s frontage, when in line, stretched out for a total width of 30 inches.

Our light infantry, the skirmishers, were composed of 10 stands of 4-men each, and when placed in skirmish line, had a frontage of about 30 inches long. The goal of our Austrian force (4 divisions) was simply to ‘hold’ we were outnumbered by a couple of battalions, and in CLS, when you’re outnumbered, about the only thing you can do is ‘hold’.

The first phase of the sequence consists of writing orders for all your units. Infantry can be given two orders, each termed an ‘operation’, and the Haub/Simon skirmish battalion was told to advance 12 inches. All other units had a ‘hold’ order. One of the orders permitted a unit is “fire” in our battle, we didn’t bother to note “fire”. Everyone thought it was rather obvious that units would automatically fire after movement.

The second phase of the sequence belongs to the horse gun. CLS gives the horse gun wondrous powers it receives 3 operations, which can be to move, to unlimber, to limber or to fire. And it gets to do all this before all other troops get to blink. Bob Liebl commanded a limbered horse gun stationed on a road leading directly across the field to our Austrian skirmish line. The distance between our troops and the gun was 24 inches. His orders were to first, advance 18 inches along the road, second, unlimber, and third, fire canister at the skirmishers. And so down the road came the dreaded horse gun... it moved 18 inches, placing it some 6 inches in front of our skirmishers, it set up shop by unlimbering on the road, and then it went BOOM! With its canister blast. Bob tossed a buncha dice (CLS uses 6-sided dice for all procedures), and 7 of our skirmishers (7 out of 40) were gone on the very first turn. After the horse gun completes its orders, the third phase takes place… all units on the field move simultaneously in accordance with the orders they were given.

French Grenadiers in two-deep line formation.

French Grenadiers in two-deep line formation.

The Bavarian horse gun was directly in front (6 inches) of our Austrian skirmish line, and there’s a gap in our line due to the 7 casualties we incurred (one 3-man stand is removed), with the gap directly in front of the gun. After our skirmish line moved its 12 inch distance, it’s now passed right through the gun, and our skirmishers have, in effect, completely ignored the dreaded horse gun, which just killed 7 of 40 men, or a little over 17 percent of the unit!

After movement, the firing phase comes next, and even if we wanted, our skirmishers couldn’t fire on the gun crew, since they were facing the wrong way!

Now, I must admit this entire episode looked kinda fishy to me… first, the gun smashes our troops and then they simply move up past it and ignore it.

The CLS rules book refers to a “moot melee”, in which two units accidentally encounter each other, without either one specifically being given charge-to-contact orders. During the game, I asked if our skirmishers would halt at the gun line, and battle the crewmen. No, I was told, orders are orders, and the skirmishers were told to advance 12 inches, and so was it written, and so shall it be done.

In past CLS games, I’ve noted that due to the lack of clarity in written orders, quite a bit of time is spent in interpreting exactly what the units will do and when they will do it, given the weasel-worded written orders and the desire of the participants (having second thoughts about what they wrote) to have their weasel-words translated as liberally as possible.

Years ago, partially due to the interpretation problems that I saw arise from the order writing phase of CLS, I became a fan of alternate move systems. Nowadays, when I look at a rules book, the first thing I do is to turn to the page detailing the sequence procedures, and if I see an orders-writing phase, I immediately close the booklet and walk on.

But now, back to the battle. After movement comes the artillery-firing phase. Artillery always fires first, followed by small arms. Artillery is most interesting, using the ‘bounce stick’. Depending upon the gun weight 6 pounder, 12 pounder, etc a ranging dowel of length 24 or 36 inches is used. The ranging dowel is divided into sections of 3 or 4 inches each alternate sections are colored red and white. Place the end of the ranging dowel at the gun barrel, and the other end right over the enemy figure you want to bash. But you’re not finished yet. Then take the 6-inch “windage” dowel, marked off into 6 inch-long divisions. Place it over the targeted figure. A toss of a 6-sided die determines which division to use, i.e., will the ball diverge to left or right, or go right up the middle. If any figures fall beneath the red sectors of the ranging dowel, these are marked off as casualties. Since the red sectors are separated by the white spaces, hits will occur as the ball “bounces” from one red zone to the next, hence the name the “bounce stick”. Interesting because there’s no dicing here merely note the unlucky men along the line of fire and remove them. Artillery that performed 2 operations (moved and unlimbered) are not permitted to fire… all other units may fire and all other fire is simultaneous.

Now it’s the small arms firing phase. As our Austrian skirmishers advanced their 12 inches, so did the Bavarian skirmishers, and the 2 skirmish lines faced each other some 8 inches apart. Formed battalions fire by stands, while skirmish units fire by figure. Our Austrian skirmishers had 33 men left (7 out of 40 had been killed by the horse gun), and so I took a pair of 6-sided dice and started to fire. I had to toss the dice 33 times. This was a multi-participant firing procedure. One guy (me) to toss the dice, one guy to count casualties (I was looking to toss 7 or more on my two dice), and a third guy to put his finger on the particular man that was firing as I went down the 33-man firing line. And after I was finished, the Bavarian skirmishers fired… remember, this was all simultaneous, and so before casualties are removed, all troops must fire. The Bavarian skirmish battalion had, I think, had the same number of men as ours, and so Cleo Liebl, the Bavarian commander, went down her own firing line, tossing dice as she went. She, too, looked for 7 or more. Cleo was immensely efficient… I can think of no other way to describe her dice tossing. When she was finished, of my original 40-man unit, I had some 2 stands left. Having been blasted well below the critical 50 percent level, our battered Austrians took a reaction test. Only the toss of a 1 on a 6-sided die would save them. Alas! And off the field they ran. And so here we were, and on the very first turn, an entire 40-man battalion of the Simon/Haub Austrian skirmishers had been wiped out.

Bavarian Lowenstein-Wertheim Regiment in Square.

Bavarian Lowenstein-Wertheim Regiment in Square.

Digression

A note on this simultaneous fire business. The concept of both sides firing simultaneously, regardless of the distance they moved, never quite made sense to me for battles set in the horse-and-musket era. Loading and preparing a musket for firing takes an appreciable amount of time. Pour in the powder, tamp, put in the ball, tamp, prime, and so on, which tells me that an entrenched, stationary force, which can devote all of its time during the bound to firing and loading, should have more fire power than an advancing force, which must devote most of its own time during the bound to moving forward.

Several popular sets of rules, for example, FIRE AND FURY, and NAPOLEON’S BATTLES, propagate such silliness, and permit both sides to blast away at each other in equal fashion during the bound, regardless of whether or not one side is sitting still, on the defensive, or running forward, trying to cover ground during the time span defined by the bound. Obviously, the epitome of historical reality. For my part, I try to ignore such rules systems. In the systems I generate, my tendency is to give both sides a number of “actions” during the bound. An action can be devoted to either moving forward or to firing volleys, hence the side on the defense, with its units mostly stationary, can devote all of its actions to firing, while the moving side must use its actions to advance, with little time for firing. But that’s just my own druthers. End of digression.

But I have yet a second digression! I must note that the firing phase, which I just described, skirmishers killing skirmishers, also resulted in transforming the game, as far as I was concerned, into a Class AA Abomination. When a casualty resulted, it was marked by placing a black casualty cap on a figure on the stand. Yuch! Pfeh! Ptui! This, to me, is the pits, which I term a Class AA Abomination. Here, we have all these good-looking painted figures on the field, and the players choose to bury them in casualty caps. But I must note that there’s an even lower categorization a Class AAA Abomination. This occurs in a skirmish game, in which, when a man is killed, his figure is simply tilted over on its side and left to rot on the field with his base sticking up in the air. No casualty figures here. Class AAA Abominations abound at the conventions, as hosts at skirmish games are either too lazy or too cheap or too ignorant to furnish casualty figures for their presentations. Another digression ended.

Back to the battle. Our Haub/Simon Austrian cannon got off a single shot before its crewmen were decimated. On the next turn, the dreaded Bavarian skirmishers struck again… still looking for a toss of 7 or more on two 6-sided dice. Four crewmen dead. Whether firing at formed infantry, or skirmishers in line, or artillery crewmen, the number to be tossed was a 7 there was no modification for the type of target. To the right of our line battalion was a woods… this was a Number 2 Woods (indicating there are at least 2 types of woods… and it turns out that CLS defines 5 types of wooded areas). While the Number 2 Woods didn’t hold up movement, it did provide cover… here, the skirmishers had to toss a 9 or more to hit. With our front-line skirmishers gone, then, on the next turn, it was time for our formed Austrian line units to fire. All formed units fire by stand, and the number of casualties is determined by the formula:

- [(Number of men on Stand) x (6-Sided die Roll)] / 10

With our 10-man Austrian stands, and assuming an average die roll of 3.5, our Austrian stands should have scored, on the average:

- [(10 Men on Stand) x (Average Die Roll of 3.5)] / 10

or an average of 3.5 casualties per dice toss. In other words, we should knock off 3 or 4 enemy casualties per toss for each of our 6 Austrian stands. Which means that we should kill from 18 to 24 Bavarians in our 6-stand firing volley. The Bavarian line battalions were slightly smaller than ours. They had 6-stand units, and each of their stands had 6 men on it. Their average rate per stand would be:

- [(6 Men on Stand) x (Average Die Roll of 3.5)] / 10

or an average of 2.1 casualties per toss. Rounding off, they score 2 casualties for each stand tossing dice, so that their 6-stand battalions would knock off a total of 6x2 Austrians, a total of 12 casualties per firing volley. But somehow, the Bavarians seemed to line up about four formed battalions against our single Austrian battalion. Their average kill rate was, therefore, 12 x 4, or 48 men per volley. And this, remember, was an average. It took only two volleys before our 60-man Austrian line battalion followed our skirmishers off the field.

At this point, the Haub/Simon command was down to a couple of cavalry units. We had lost a gun and two full battalions of infantry the Austrian left flank didn’t look too well. The opposing commander, Cleo Liebl, didn’t seem to have lost anything except her own skirmish unit. And so, down to our cavalry, what else could we do but shout “CHARGE!”

On the next turn’s order-writing phase, we told our Cuirassiers to charge. We had two squadrons, each of 2-stands, of Cuirassiers. Both squadrons went in. But Cleo had her own heavy cavalry charge, and so the heavies paired off in midfield. In melee, just as in skirmish firing, each figure gets a hack at the enemy. Simultaneous dice tosses are used. There are two parameters of interest:

Vulnerability: This, in essence, is a defensive factor. The sides toss two 6-sided dice, and if a toss equals or exceeds the other by the Vulnerability number, a casualty is scored. Thus, my Cuirassiers had a Vulnerability of 4, and the Bavarians had to exceed my dice toss by 4 to score on my heavies.

Combat: This is a combat value added to a side’s dice toss. This is an offensive factor. My Cuirassiers’ value was a +4, so that they added, each toss, a factor of 4 to the dice throw.

Cleo and I started to toss our dice simultaneously, looking to roll 4 more than that of the opponent’s. What juices up the melee system, however, is the implementation of a morale testing procedure within the melee procedure. During the opposing-roll procedure, if a side tosses doubles, the opposing unit is forced to take a morale test. Here, when Cleo tossed doubles, I had to throw 5 or more for a successful test, whereas Cleo’s unit had to toss 4 or more. Bad luck for Cleo, her unit failed a morale test and took off, leaving me with one 2-stand Cuirassier squadron, a pitiful remnant of the original Haub/Simon force. Although way back on our baseline, I noted another small squadron or two useless! Useless! I was told that because our heavies had driven off the opposing cavalry, the Cuirassiers had a bonus move. That was all I needed. Here was a chance for our horsemen to die with their boots on! “CHARGE!” Into the opposing formed Bavarian infantry went the heavies.

And, since we got a bonus move, the Bavarians got a bonus fire. And there went the last of our Cuirassiers.

In this story, I’ve concentrated on the Austrian left flank, where the Haub/Simon contingent was in action. I didn’t pay too much attention to the rest of the field… I assume that, there, too, people were firing on and killing and maiming each other, but I have no idea of the resulting carnage. After all, the left flank was where the real action took place, and all the rest was mere diversion, n’est pas?

In 1973, when it was published, CLS was it, i.e. ‘state of the art’. One of the comments made at our game was to the effect that the rules provided a good mix of tactical ploys for the Napoleonic era. But let’s face it… CLS was a silly game when it first came out, and it’s a silly game today.

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet Fall 2002 Table of Contents

Back to Novag's Gamer's Closet List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Novag

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com