During the development of Fear God & Dread Nought (FG&DN), there were a number of important historical issues that we tried very hard to translate into the rules. One of these

dealt with the significant advances in long-range gunfire control that began around 1910 in virtually all navies. In particular, we wanted to show the difference between those systems that could automatically determine range rate and bearing rate, such as Pollenís Argo range clock and the MkIV Dreyer Table, and those that couldnít.

During the development of Fear God & Dread Nought (FG&DN), there were a number of important historical issues that we tried very hard to translate into the rules. One of these

dealt with the significant advances in long-range gunfire control that began around 1910 in virtually all navies. In particular, we wanted to show the difference between those systems that could automatically determine range rate and bearing rate, such as Pollenís Argo range clock and the MkIV Dreyer Table, and those that couldnít.

To cut to the chase, we did provide all the necessary rules to account for the various types or modes of fire control on pages 6-1 and 6-2 in the FG&DN rules booklet. But what we forgot to include in either the rules or in Annex A was which ships had which type of system and how many directors did a ship have for its primary and secondary batteries. The only answer that we could give once we realized that we had dropped the ball on this was to hit our foreheads and say, to quote Homer Simpson, DOH!

How this could have happened wasnít all that hard to figure out, now that we knew where to look. Basically, it was the case of being too close to a project for too long -- we couldnít see the forest for the trees and our numerous reviews kept looking at those leaves that had caused us the most trouble during the game design phase. We arenít trying to make any excuses for screwing up, rather we acknowledge this error on our part and the need to fix it.

This article provides the missing data needed to play out this interesting and significant facet of the Great War at sea. Because of space constraints, this will not be an in-depth discussion of the types of fire control equipment used by the various navies. [Ed Note: much as Chris would love to]

Rather, it will just list the general types of fire control used by a particular nation, or class of ship, along with the number of primary and secondary directors and roughly when they were fitted.

Director Fits

For the most part, the navies of WW I allocated directors to their ships uniformly. The largest exception also happens to have been the largest navy during the war - Great Britainís Royal Navy (more on that in a moment). Virtually every navy that saw action in WW I began installing directors on their ships between 1908 and 1912. Thus, the installation and procedures on how to use directors were already thoroughly integrated in to each nationís fleet by the beginning of WW I in August 1914.

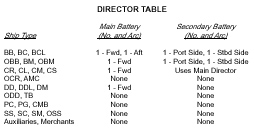

The typical director fit based on ship type is listed as follows in the Director Table. While there is a lot of good data on dreadnought director fits, the same cannot be said of pre-dreadnoughts. From the limited data available, it would appear that only those pre-dreadnoughts that were built after 1900 were ever backfitted with directors. While this was not universal in all navies, it is a reasonable assumption for the purposes of playing FG&DN.

There is little data on when smaller ships received their directors. For the most part, it seems that the Germans fitted directors and fire control equipment on their Scharnhorst and BlŁcher classes of armored cruisers and light cruisers early on (before 1914). Tr eat BlŁcher as a battlecruiser for the purposes of director fit. The Royal Navy and most of the Allied nations, with the possible exception of Russia, did not fit directors on their light cruisers until 1916-1917. Based on almost a complete lack of data, it appears that Allied armored cruisers, again with the possible exception of Russia, were not fitted with directors. Destroyers are even more difficult to pin down. While there is information that states destroyers had directors, there is very little on when they received them. As with light cruisers, German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian destroyers appear to have received directors before the other navies. It is reasonable to assume that the RN and the other Allied navies didnít install directors on their destroyers until 1916-1917.

Each director has all the necessary equipment and personnel to sight/aim the guns on a particular target and either issues firing orders to the guns or fires the guns remotely. The business of collecting target data and calculating the firing information for the guns is done in a central fire control position that is usually separate from the director itself.

There is little to distinguish the performance of one fire control philosophy and technology from another. Although considerable debate has gone on over the years arguing that a particular navyís director scheme was better than the another, there is little difference between most fire control approaches in terms of the number of hits achieved during battle. Therefore, with the exception of the Arthur H. Pollenís automatic Argo range clock, all other director concepts and equipment are treated as having identical performance in FG&DN. The only countries that did use the Argo range clock, or a system similar to it, were Great Britain, Russia and the United States.

Fire Control Systems

The Royal Navy

Great Britainís Royal Navy (RN) had a difficult time making up its mind on which fire control system, Arthur Pollenís or Frederic Dreyerís, the fleet would use and it had a difficult time getting sufficient sets made to outfit all of the capital ships. By the beginning of the war, just over a quarter of the RNís dreadnoughts had a director for their main batteries and none of them had directors for their secondary batteries. And of these, only Queen Mary, Conqueror, Centurion, Ajax and Orion had an Argo range clock as part of their fire control system.

However, many of the RNís later battleships and battle-cruisers were fitted with the MkIV/IV* Dreyer table that also provided range rate and bearing rate information automatically. The classes of ships thus fitted include Queen Elizabeth, Revenge, Lion (after 1916), Tiger, Renown, Courageous and all but one of the Iron Duke class (Marlborough had a MkI Dreyer table). Of note, the Dreyer-Elphinstone clock used in the MkIV/ IV* bore a striking resemblance to Pollenís Argo clock and would be the major point of a patent infringement trial in 1925.

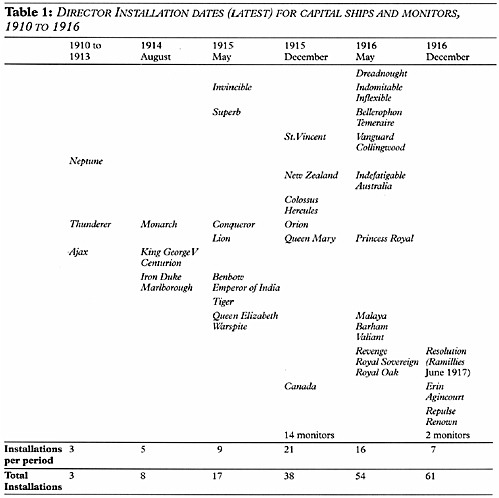

The main director issue was almost completely remedied by the Battle of Jutland, with only Agincourt and Erin still lacking the equipment, however, all of the dreadnoughts still lacked secondary battery directors even at this late date. Unfortunately, due to either funding constraints or the waxing and waning of the influence of the director lobby, all battleship classes after the Orion class and all battlecruisers after the Lion class have only one main director forward. The date of installation of the main battery director (the Scott Director) is listed in a table taken from John Brookís article in Warship 1996 entitled Percy Scott and the Director, on page 168.

The secondary director problem would finally be addressed after the Battle of Jutland, starting in November 1916 when the Royal Navy began a crash program to outfit their dreadnoughts with secondary battery directors. Those ships with 6-inch casemate batteries received the secondary directors first, followed by other ships as they came in for refit with the process completed by July 1918.

Imperial Russian Navy

While Russia had its own producer of fire control equipment in the competent Geisler & Co. located in St. Petersburg, the Russian Navy was nonetheless intrigued by the claims of Arthur Pollen. After technical discussions in late 1913, the Russian Navy purchased four sets of instruments that were subsequently installed on the four Gangut-class battleships. Thus, only the forward main director on these battleships will get the Pollen type fire control bonus. The after main director is of purely Russian manufacture and the fire control bonus is not applicable.

United States Navy

The U.S. Navy largely followed the Royal Navy in their concept of the director, although there were some differences as to when certain functions, such as single key or centralized firing of the guns was adopted. As the possibility of the United States becoming directly involved in the great European war loomed larger, the U.S. Navy ordered large numbers of the Ford Rangekeeper MkI which was very similar in operation to Pollenís Argo range clock. Initially accused of patent infringement by Pollen, Ford engineers were able to satisfy the British inventor that their approach was of Fordís own development.

The first order for the Ford Rangekeepers (Mks I and II) was let in late 1916, and by the end of hostilities over 930 sets had been delivered to the navy.

Given the rapid production, it is very probable that the dreadnoughts of Battleship Division Nine (New York, Wyoming, Florida and Delaware) that were dispatched to Great Britain were all equipped with the new Ford Rangekeeper MkI in both the forward and after directors.

Unfortunately, the U.S. also followed Great Britain a little too closely on the issue of secondary directors and it wasnít until after the U.S battleships joined the Grand Fleet that they saw the utility of secondary battery directors. So impressed were the U.S. naval officers with the British Vickers director, duplicates were ordered by the Bureau of Ordnance in October 1917. The secondary directors, however, would not be installed on U.S. battleships until after the war.

Conclusion

The director issue is one of the dominating issues in discussions of naval warfare during WW I. The impact of the director and automatic fire control on naval gunnery, while hotly debated was eventually accepted by all navies as key components if accurate long-range fire was to be obtained. While there were numerous different ways to implement the fire control concept, the only one that stands out as being better than the others was the one employed by Ford and Pollen, and copied by Dreyer, which could automatically solve a differential equation mechanically and provide a more accurate range rate and bearing rate information.

The remaining approaches, while diverse, all provided about the same hit chance during actual battles and therefore, do not need a special modifier in FG&DN. Since wargaming is an excellent tool in the investigation of history, it is hoped this article provides players with a better understanding of what went into the gunnery system in FG&DN, as well as the important ship director fit data that was unfortunately left out of the published game.

Sources

Schleihauf, William: The Dumaresq and the Dreyer Part I, Warship International, Vol. No. 38, No. 1/2001, pages 6-29.

Schleihauf, William: The Dumaresq and the Dreyer Part II, Warship International, Vol. No. XXXVIII, No. 2/2001, pages 164-201.

Schleihauf, William: The Dumaresq and the Dreyer Part III, Warship International, Vol. No. XXXVIII, No. 3/2001, pages 221-233.

Brooks, John, ďThe Mast and Funnel Question Fire-Control Positions in British Dreadnoughts 1905-1915,Ē Conway Maritime Press (London, 1995), pages 40-59.

Brooks, John, ďPercy Scott and the Director,Ē WARSHIP 1996, Conway Maritime Press, London, 1996

Groves, Eric, Big Fleet Actions, Arms and Armour Press, London, 1995

Friedman, Norman, U.S. Battle-ships: An Illustrated Design History, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1985

FG&DN Director Annex Specifications (monstrously slow: 773K)

BT

Back to The Naval Sitrep #23 Table of Contents

Back to Naval Sitrep List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Larry Bond and Clash of Arms.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history and related articles are available at http://www.magweb.com