With the publication of Fear God & Dread Nought, the Admiralty Trilogy (AT) now spans the entire 20th Century. We have three games that model air combat throughout the history of aviation, using common rules and rating systems. Sort of. All the planes in the AT games have Maneuver Ratings, measuring their ability to gain position on an opponent in air combat, and their ability to avoid someone doing it to them.

The Maneuver Ratings look similar - numbers in increments of .5 that are plugged into the same formula for all three games, showing the chance of gaining position on an opponent. Same numbers, same formulas, so everything’s the same. Right? But are they the same? In the AT, three “eras” were established separately as the games were developed: WW I, WW II, and the “modern” era, roughly 1980 to the present day.

As the games were developed, there was no plan to have planes from one game appear in another. Although they are all numbers that use the same rules, they use different subjective scales, and a 3.0 in one system may not be the same as a 3.0 in another.

Why Worry About It?

If you compare Maneuver ratings in different games, it is possible for two combat aircraft from different eras, e.g., a P-47 and a MiG-23, to have the same ATA rating. But they are not a match. The MiG-23 would still gain firing position almost every time, assuming pilots of equal skill, and ignoring the MiG’s superiority in weapons and sensors. The MiG-23’s speed would give it a tremendous edge.

We’re not trying to match up Zeroes and F-14s, Final Countdown notwithstanding. Keeping the ratings consistent between eras is important, though. Each aviation era tends to “leak” into the next. Aircraft built with late WW I technology (Gladiator, Fiat CR.42) fought in WW II. WW II-era prop planes (P-51, Sea Fury) fought jets over Korea, and later took part in the Vietnam War (Skyraider, A-26), two “eras” after their development. The opportunity for air-to-air encounters “across games” exists in almost every conflict where aircraft were used.

What if it happens in a scenario?

Can players match up a late WW I plane with an early WW II aircraft and expect a fair result? There’s also the matter of consistency. The interwar eras will soon be covered by new games now in development. Biplanes and Battleships will cover 1924 - 1939, and Stars and Stripes will cover the 1960s and ’70s.

If we add the new planes to an existing game, which scale should we add them to? Many planes in B&BB use WW I technology, but the game will also include planes that later served in WW II, and they need to be compatible with CaS.

What Exactly do the Ratings Represent?

The Maneuver Rating measures a plane’s ability to get into firing position on a hostile aircraft and prevent an enemy from getting into firing position itself. The weapon with the narrowest envelope is a gun, so that is that standard used for comparison. Maneuver Ratings consider a plane’s instantaneous turn rate, roll rate, and other such statistics, and basically describe the ability to quickly change direction. Additionally, I factor in energy, which is the ability to keep up speed while and after it makes a sharp turn. Any plane can make a hard turn, but some will fall from the sky like bricks because they’ve bled off too much speed. Others may stay up, but they’ll be so slow my grandmother could whack them with a broom. What we define as “maneuverable” really means, “can turn quickly, keep up speed, then turn again.”

In 1982, during the Falklands War, I talked to a Nimrod pilot about the (then recent) arming of Nimrods with AIM-9s. He insisted that this gave them a real chance against Argentine Mirages. Because of the Nimrod’s low wing loading, “they could turn inside a Mirage.” And he could - once. Low wing loading is an advantage for a fighter, but having low wing loading doesn’t make you one.

How Are the Maneuver Ratings Derived?

First, there is no formula for computing a plane’s Maneuver Rating.

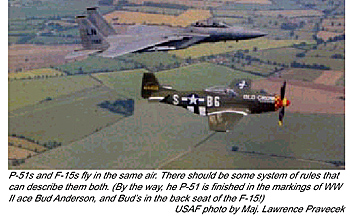

P-51s and F-15s fly in the same air. There should be some system of rules that can describe them both.

The P-51 is finished in the markings of WW II ace Bud Anderson, and Bud’s in the back seat of the F-15! USAF photo by Maj. Lawrence Pravecek.

The P-51 is finished in the markings of WW II ace Bud Anderson, and Bud’s in the back seat of the F-15! USAF photo by Maj. Lawrence Pravecek.

I’ve tried to develop formulas over many years, using several different approaches. They all failed, because in the end, you have to judge the computed result against your own subjective assessment of the relative merits of the aircraft. So, in the end, I’ve just relied on that “gold standard,” and done a lot of reading. (Darn, I have to read more books about airplanes.)

Recognizing that there is a certain lack of precision in a subjective approach, I've restricted the Maneuver Rating to increments of .5, that representing a substantial increase in the maneuverability of one plane when compared to another.

Bottom Line

The Maneuver Ratings depend on comparisons of the relative merits of two potential opponents in a dogfight. If they’re a match in the air, then their Maneuver ratings should be the same, implying that in a fight, each would gain firing position on the other half the time, given pilots of equal ability. The goal is to “gain firing position,” so it is independent of the weapons they carry. Luckily, there are plenty of books comparing this aircraft to that one, or discussing a plane’s relative merits vis-a-vis potential or actual adversaries.

The problem with this information is that it only covers aircraft that are contemporaries. Nobody compares aircraft from different eras because they never met. Thus, you can’t “link” the three eras with a common scale.

Why Try to Have a Single Scale?

What if two planes of equal ratings planes are of different eras? The Gloster Gladiator is described as “nimble,” and “very maneuverable,” but nobody would willingly pit it against a Me 109 or a Zero. It has also been described as “the best WW I fighter ever built.” It was slow, and underarmed, and obsolete at the start of WW II. Even if the Gladiator had a decent armament, it would still have a hard time getting a shot at a front-line WW II aircraft, because of their speed advantage.

The situation would be similar with a P-51 up against a MiG-15 in the Korean War. The MiG has all the zoom, and the P-51, even though it can “turn inside” the MiG, is still at a disadvantage.

The Speed Modifier

The more modern plane always has an advantage, assuming they’re both of the same general type. Exactly what qualities does a later plane possess? Speed. No matter what else they can do, later planes always can go faster.

In a fight, speed can be traded for altitude, or energy for a turn, or left as speed, to close or escape as desired. The faster guy has all the options.

I've added a rule in CaS that for every 150 knots of speed advantage that one plane has over the other (at combat cruise), the faster plane gets to add 0.5 to its effective Maneuver Rating. This rule was deliberately created to deal with the Gladiator vs. Bf 109 issue, but once I had it down on paper, I realized that it reflected the difference between two different eras of aviation development.

And what about Final Countdown?

Can the rule be applied to jets vs. props?

The speed differential rule does allow a Zero to dogfight an F-14. The Zero’s Maneuver Rating is 3.5, the F-14’s is 4.0. (Right there, you can see they’re not on the same scale). With combat speeds of 150 knots and 765 knots respectively, the differential turns into a maneuver rating modifier of +2.0. Then add a Vulcan cannon and it's not a very fair fight. Which we knew it would be. But now we can say exactly why, and just how bad it will be.

Does the Speed Modifier Put All the AT Planes on the Same Scale? Almost. One of the things that kept popping up as we tried to find a common scale was the issue of technology. Why do later planes go faster? Better engines, better airframes, better understanding of aerodynamics. But aircraft technology wasn’t driven just by the need for more speed.

As aviation technology has advanced, aircraft have not only become faster, but more maneuverable. WW II fighters can pull G’s and make maneuvers that WW I fighters found impos-sible. Jets like the F-16 can make use of the vertical dimension in ways that were impossible in WW II. The latest jets, using canards and computer-controlled flight systems, can do exotic maneuvers or even perform “nonballistic maneuvers.”

Thus, aircraft technology defines the eras, and the upper end of the Maneuver Rating scale keeps increasing.

- Early Flight: Wooden frames, fabric, primitive engines: 3.0

Interwar Years: Metal frames, fabric or metal skins, still biplanes: 3.5

WW II: Monoplanes, monocoque construction, streamlining: 4.0

Postwar: Jet propulsion, low thrust-to-weight ratios (somewhat underpowered): 4.5

Mid-80s: Jets with high thrust-to weight ratios, fly-by-wire flight controls: 5.0

Present Day: Canards, thrust-vectoring engines: 5.5

[Note: The only problem with this nice progression is that there are WW I planes in the game right now with a maneuver Rating of 4.0. When we developed FG&DN, I was trying to spread the WW I planes out over the same range as CaS. Those ratings were assigned years ago, before this became an issue. Eventually, they will have to be re-rated. This is not a huge problem for the moment, since few of these planes saw service after 1918.]

What Changes Do We Have to Make to the Rules?

Aside from the speed modifier rule itself, we need to look at the rules for slashing attacks. This type of attack was rare before WW II. Pre-WW II aircraft (biplanes) could seldom build up enough of a speed differential. Even in WW II, you got the speed advantage needed by diving from a higher altitude.

A WW II slashing attack was a diving attack, and required time to set up - you had to get above your opponent, unless you were lucky enough to start there. Even so, your initial position only bought you the first pass.

It also was designed to carry you out of the fight before the other side could counterattack in an organized manner. Thus:

- Advantages: Helps gain position, limits exposure to enemy counterfire

Disadvantages: Takes longer, involves a dive (the only way to get the required speed)

If we’re using a plane that’s just faster, with a +50 kt delta, then he doesn't need to dive. He's still in and out of the fight as before, and he doesn't need to set up. But what if the attacker elects to “stay with” his target after the first attack, or enter a turning fight? We tend to class it as a Bad Idea, since a slashing attack has a lot of advantages. To stay with a target, a slashing attacker would have to dump a lot of speed very quickly.

Imagine a MiG-15 vs. a P-51. The P-51's all over the place and the MiG-15 elects to stay with the prop (maybe the pilot’s trying to get his tail number). In game terms, he has abandoned the speed differential modifier. This means a direct comparison of Maneuver Ratings, and a much better chance of the slow plane getting a kill, along with bragging rights that night at the club.

But it’s a Dumb Move. The MiG gains nothing, and loses a lot. It’s not an option, just a way of distinguishing dumb pilots from smart ones.

Rule: Any plane with a +50 knot superiority can declare a slashing attack, as before, but if it the superiority comes from a higher speed, without the need to dive, it only leaves the dogfight for one 30-second air combat round.

Rule: Because he’s going so fast, the other plane can’t get a parting shot on the Dogfight Break-Off Table, unless he’s got a heat-seeker. Since the attacker doesn’t stay behind his victim, there’s a chance (compare base Maneuver Ratings) that the defender (if he survives), is in position to get off a heat-seeker or a dogfight-capable radar-guided missile as the slasher leaves the scene.

What About IR missiles Vs. Piston-Engine Planes?

All the attack areas are reversed, since the hot spot is on the front of the plane, not in back.

Also, piston engines are not as hot as jet engines, so there is a -1.0 modifier to the missile’s ATA rating when it is used against a piston-engine aircraft. Not turboprops - they’re jets and have a hot tailpipe. We’re talking just radial and inline piston engines.

What about Helicopters?

The speed modifier also “solves” the problem of helicopters. As a group, they have a much better turn rate than fixed wing aircraft, but nobody considers helicopters and high-performance fighter aircraft an even match.

We will reevaluate the Maneuver Ratings of helicopters and publish any changes necessary.

An Example

The Korean War saw many jet vs.prop encounters. One of the first air battles was an attack by 2 F-80s on 7 Il-10 ground attack planes. The North Koreans lost four Il-10s.

The US also used prop planes for attack missions, including the F4U-4B. It could carry a much bigger load than the early jet fighters.

In mid-November of 1950, a strike from Valley Forge was attacked by a formation of MiG-15s. The F9F Panther escort was overmatched by the MiGs, and the enemy fighters reached the strikers, a mix of Corsairs and Skyraiders. (Form 20s for the F4U-4 and MiG-15 appear on pages 24 and 25.)

The MiG-15 was designed as a high-altitude interceptor, fast and fitted with a heavy armament, but only moderately maneuverable. Its lightly loaded Maneuver Rating is 2.5. The Corsair is a good (maybe great) late WW II fighter-bomber. Its loaded rating is 2.0, but if attacked, the pilots would jettison their loads, raising its Maneuver Rating to 3.5.

The MiG-15 is faster. At medium altitude (where the fight takes place) it has a combat cruise speed of 410 knots, compared to the Corsair’s 350 knots. This is enough for an automatic slashing attack, but not a speed modifier.

The MiG-15s will be able to make one free slashing attack, then spend one turn out of the fight as they reposition. They will not be subject to any counterattacks.

The F4Us’ best move at this point is to go defensive. This adds .5 to their air-to-air ratings and makes the chance of a hit (3 + 2.5 - (3.5+.5)) * 10% = 3 + 2.5 -4 * 10% or just 15%. This is good, because if the MiG connects, it’s curtains.

What about Guns?

I actually revised the Harpoon gun attack factors in Naval SITREP #18 (April 2000) so they used the same formulas as CaS. This made them more consistent within Harpoon, but they are on a different scale. You have to multiply the new Harpoon values by 2.5 to get them on the same scale as CaS. The planes in FG&DN use the same gun values as CaS.

If we revise the gun damage values in Harpoon to put them on the same scale as the two other games, then we have to provide the planes in Harpoon with Damage Ratings like CaS and FG&DN. Those values would be higher than their WW II brethren, and will have to wait for another day.

What’s Next?

As time permits, we’ll review all the Maneuver Ratings for consistency. Most will be fine. Helicopters will need a special scrub. We’ll publish the results in future articles of the Naval SITREP. The new rules will be added to the list of changes to be made for the next edition..

BT

Back to The Naval Sitrep #21 Table of Contents

Back to Naval Sitrep List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Larry Bond and Clash of Arms.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history and related articles are available at http://www.magweb.com