First Steps

The first Italian experiments on radio detection and finding were carried out by Guglielmo Marconi in 1933. He began a series of experiments with radio waves of 90 cm, developing an experimental apparatus in 1935. Great emphasis was given to his work by the fascist propaganda after a demonstration in front of Mussolini.

E3C/ter on Littorio

E3C/ter on Littorio

That exposition also gave birth to the legend that is going on still today: Some journalists found a burnt animal (actually a roasted sheep) in the area near the site of experiments and reported that Marconi was testing a "Death Ray"! After too much publicity, the worsening of Marconi's health (he suddenly died in 1937) and the deterioration of the relationships with Great Britain during the Ethiopian crisis (the Marconi company of Genoa was a British holding), the Armed Forces decided to give the experimental program to the young professor Ugo Tiberio.

He was transferred to the RIEC (Regio Istituto di Elettrotecnica e delle Comunicazioni della Marina, "Royal Electronics and Communications Institute of the Navy", a.k.a. MARINELETTRO from its tele-graphic name) in Leghorn, where a dedicated section was established, but poorly funded. Actually, Tiberio was the only member of that section, and he also had to share his time with teaching at the Naval Academy.

The first experimental apparatus was developed in the winter of 1936. Named EC-1, it was an RDT (Radio-Detector-Telemetro, in Tiberio's own definition) based on a frequency modulated continuous wave of 200 MHz. It had a cylindrical parabolic antenna, and used the new 800 RCA triodes of 100 W power manufactured in the USA. It was used to verify the 'fourth power law' and measure the background noise. It had a limited range of 2,000 m with a motorboat as the target.

The new EC-1/bis of 1937 was a modified version of the EC-1 with a superheterodyne receiver. It was very unsuccessful and Tiberio decided to experiment a new pulse wave apparatus, having followed the way of the frequency modulation only for the limited capabilities of Italian industry of the time.

This new pulse wave radar was named EC-2. It had a 1.70 m wave-length, a lattice antenna, and the transmitter used the 800 RCA triodes. It proved to be unreliable because of the transmitter's poor-quality electronic components and the low peak power of 1 kW. So Tiberio returned to the continuous wave experimentation, and only after one year he decided that it was a dead end. After these initial failures in the development of a shipboard radar set and rumors of British achievements, the Direzione Armi Navali (Naval Weapons Office) contracted with a private company for the realization of a prototype of a radar with a 2 m wavelength. After months of negotiation, at the beginning of 1939 the SAFAR (Società Anonima Fabbricazione Apparecchi Radiofonici, Radio Devices Manufacturing Anonymous Company, founded in 1932) of Milan rejected the project.

Further Developments

In spite of the many failures and the underestimation of foreign achieve-ments in the field of radio detection, during 1938, Tiberio developed two new radar sets. One was a 70 cm pulse wave apparatus with a double truncated pyramid-shaped antenna, and the other was similar, operating with a 1.5 m wavelength and a rotating lattice antenna.

This second set (subsequently named RDT-3) gave good results, but due to its weight, the RIEC decided to further develop the "horn antenna" apparatus, newly named EC-3. The EC-3 had a 70 cm wave-length, two small trunk antennas (2 square meters each) and the new Phillips PA 12/15 triodes, while the receiver used the RCA 955 triode. The plotting of the track was acoustic, on the frequency of the 600 Hz note, because of the unreliability of the oscilloscopes made in Italy. In spite of its low power (less than 1 kW) it had a 30,000m air range, but proved to be useless. The prototype was completed in 1940, just before the Italian declaration of war on Great Britain and France.

At this point it is important to clarify one thing. The Kriegsmarine was one of the first navies to embark a radar set on its ships (the pocket battleship Graf Spee had a DeTe in 1939 at the outbreak of the war), so we could ask: did Germany inform her Italian ally of their advances in the naval radar research? The matter has given rise to much controversy among Italian historians after the war, and the German Navy was accused to have been silent about their "Dezimeter Telegraphie" until the aftermath of Matapan (see below).

Nowadays, after the publication of the Seekriegsleitung diary, we know that admiral Raeder (CinC of the Kriegsmarine) ordered on 11 June 1940 to share their secret naval technology with their Axis ally.

In June 1940, an Italian mission was soon sent in Germany to investigate, but it wasn't the best example of military cooperation between the two navies. The Germans showed only one of their oldest "Freya" coastal radar (that was too cumbersome to be employed on board any warships) while the Italians kept secret all their radio detection experiments. So, due to the underestimation of the achievements of the enemy powers, the closure of imports of RCA thermoionic tubes from the United States, and the firm belief that the war would last only a few months, the radar research was virtually put to an end in July 1940.

Only in December 1940, realizing that the war would last longer than expected, and thanking Tiberio's perseverance, the work was resumed.

In February, 1941 a new prototype was completed. The EC-3/bis, derived from the EC-2 had a peak power of 1kW, using the Phillips PA 12/15 triodes, purchased before the German occupation of the Netherlands. It had an estimated air range of 25,000 m and a naval range of 10,000 m; the plotting was still operated acoustically.

Emergency Modification

On the night of 28 March 1941, near Cape Matapan, the British cruiser Orion spotted, with a Type 286 radar set, the Italian heavy cruiser Pola from 6 miles away, stationary and obscured. After a fierce engagement, three Italian heavy cruisers and two destroyers were sinking, with no loss on the side of the Royal Navy. After the analysis of British radio messages and the fact that six miles was beyond visual sighting range, the Regia Marina realized that radar detection was a reality for the Royal Navy.

E3C/ter on Fuciliere

E3C/ter on Fuciliere

What followed was a hasty race to make up for lost time. The interdepartmental committee, renamed in May 1942 RaRi (Radio-detector-telemetRi), issued its new directions:

- 1. Production of 50 EC-3/bis for air warning on board of the ships.

2. Development of the RDT-3 for land based early warning against air raids.

3. Mass production of thermoionic tubes by the Italian industry.

4. Starting research for a new airborne radar set.

The EC-3/bis prototype was embarked for a series of tests, in May 1941 on the torpedo boat Carini, and in August 1941 on the battleship Littorio. Because it could not train in azimuth, it was installed on the forward side of the second main director. It proved to be unreliable (due to the weakness of the electronic components) and useless (it was impossible to use the acoustic plotting over the background noise), so it was disembarked in May 1942.

At the same time, Germany started to supply five new FuMo-24/40G sets. The first Seetakt arrived by the end of 1941 and was installed on the destroyer Legionario in March 1942. It was the first operational radar set on board an Italian ship, and was used actively during the "Mid-June" and "Mid-August" Operations. On the other hand, the other four German radars were transferred only after the end of 1942, following the worsening of the relationships between the two navies in the winter (so that even the Italian Air Force had to purchase at a high price its Freya, Würzburg and Löwe land-based radar sets).

Germany also supplied the Regia Marina with sixty Fu MB 1 "Metox" radio detectors. Starting from August 1942, they were installed on the Betasom submarines (the ones operating from Bordeaux into the Atlantic), and then on battleships, cruisers, torpedo boats and the other submarines in the Mediterranean.

With the production of the new 1628 tube by FIVRE (Fabbrica Italiana Valvole Radio Elettriche, Italian Radio Electric Valves Factory), capable of 10 kW peak power, it was possible to design two new radar sets: the EC-3/ter Gufo ("owl") and the RDT-4 Folaga ("coot"). So, the original order of 50 EC-3/bis was changed in December 1941 to fifty EC-3/ter Gufo, with other additional fifty sets to follow. The production of the Folaga was assigned to the Marelli company, the Gufo to SAFAR and "Allocchio & Bacchini", while FIVRE manufactured the tubes (actually at the very slow rate of three Gufo per month). A total of 800 Gufo and 55 Folaga sets were ordered before the armistice.

The first EC-3/ter Gufo prototype was installed on Littorio in September 1942, and this time it proved to be quite reliable and with performance comparable to that of the German DeTe set. Apart from the first Gufo prototype, all the other sets were installed on top the foretop director on battleships and destroyers, or on top of a purposely-made tripod or mast abaft the tower on cruisers. Nevertheless it still suffered from a serious mechanical flaw: its training Ward-Leonard unit was underpowered, so it was impossible to train the antenna in a strong wind or when steaming at high speed.

To 8 September 1943 (the date of the Italian surrender and armistice), only 13 Gufo had been installed (the Littorio prototype and 12 production models), while one more set (due to be mounted on the cruiser Trieste, but sunk by an air raid) was used for training duties in Leghorn. The battleship Cavour, the cruisers Gorizia, Duca d'Aosta and Pompeo Magno, and the destroyer Grecale were ready to receive their Gufo apparatus when the Armistice put it to an end. The installation of the Gufo was planned for the never-completed carrier Aquila, the Etna and Vesuvio cruisers, the 'Comandanti Medaglie d'Oro', Spalato class and second group 'Soldati' destroyers, and the Ciclone-class escorts.

FuMO 24 on Oriani

FuMO 24 on Oriani

At the same time, 50 Folaga sets were ordered by Regia Marina, to be employed for coastal air warning in naval stations, but by July 1943 only eight were provided by the Marelli company. They were four "Folaga O" preproduction sets (3 in Taranto and 1 in Venice) and four "Folaga I" produc-tion sets (1 in la Spezia, 1 in Taranto, 1 in the Nettunia RaRi school and 1 in Pratica di Mare for testing). The Folaga was used for air and surface search, and as an aid for the German Würzburg radar. The Würzburg was renamed Volpe ('fox') in Italian service and used for aiming the flak batteries. 21 sets were supplied by Germany to September 1943, but only a few were operational by that date.

By the start of 1943 also a Lorenz radar, renamed Leone ('lion'), was delivered for training duties, waiting for the more modern Würzburg.

After the Armistice

FuMO 31 on Abruzzi

FuMO 31 on Abruzzi

After the Armistice, Italian light ships cooperated with the Allies to fight the Germans, so in 1944 some Italian cruisers were equipped with British radars to operate in the central-southern Atlantic. They were soon removed after a few months. On the other hand, Germans sized some Italian light units in port or under construction, and refitted some of them with their own radar sets. In Spring 1943, the RIEC had developed a EC-3/quater, soon renamed GIII. It had a single parabolic dish antenna. After the Armistice, the Kriegsmarine estimated it was superior to their apparatus, and planned to produce it under licence in Germany. In 1944 a few GIII were installed on board of torpedo and escort boats.

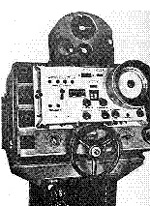

Gufo Control Panel

Gufo Control Panel

The armistice of 1943 ended all Italian developments and projects; some of them are described below:

- "Razza" ('ray, skate'): it was an airborne surface search radar, built for the Regia Aeronautica (Royal Air Force) and installed on a S.79 airplane. It was a copy of a British ASV II radar set, captured from a Wellington plane shot down in the night of 28 March 1942 near Patras in Greece.

- "Argo" ('Argus'): an airborne surface search radar (range = 35 nm) installed on a S.79, and then a Cant Z.108 airplane (naval surface radar, one apparatus used on a S.79 and then a Cant Z.108 aircraft)

- "Vespa" ('wasp') and "Lepre" ('hare'): a night air interception radar

- "Lince" ('lynx'): was a radar manufactured by the SAFAR company. Two versions were developed: a night air interception ("Lince Vicino") and a naval surface search radar ("Lince Lontano"). It was used for a time by the Italian Social Republic of northern Italy, under German control.

Bibliography

Enrico Cernuschi, Marinelettro e il Radiotelemetro Italiano - Lo Svilupo e l'evoluzione del radar navale (1933-1943) - Supplement to "Rivista Marittima" n.5 May 1995

Augusto de Toro, Il radar tedesco e la Marina Italiana: ne fu informata l'11 giugno 1940? - "Rivista Italiana Difesa", April 1990

Erminio Bagnasco, Le Armi delle Navi Italiane nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale, Albertelli, 1978

Nino Arena, Il radar - vol.1, La guerra sui mari, STEM-Mucchi, 1976

Orizzonte Mare - Navi Italiane nella 2 a Guerra Mondiale, Corazzate classe Vittorio Veneto, vol. 3/I, Edizioni Bizzarri, 1973

Orizzonte Mare - Navi Italiane nella 2 a guerra mondiale, Incrociatori leggeri classe Condottieri, vols. 7/I, 7/III, Edizioni Bizzarri, 1982, 1985

Alberto Santoni, Lo scontro di Gaudo e la tragica notte di Matapan -" Rivista Italiana Difesa", March 1991

Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships (1922-1946), Conway's Maritime Press Ltd., 1980-1987

La Marina Italiana nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale, vol.XXI -L'organizzazione della Marina durante il conflitto, tomo II, Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, Roma, 1975

Italian WWII Radar Technical Specifications and Installations

BT

Back to The Naval Sitrep #17 Table of Contents

Back to Naval Sitrep List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Larry Bond and Clash of Arms.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com