Ed Note: This article is an adaptation of a brief given by John D. Gresham at the Connections '99 conference at the Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell Air Force Base in February.

During the six months from August 1998 to February 1999, the United States of America made unprecedented use of airpower as a diplomatic and national security instrument. Four major operations took place:

- Retaliatory missile strikes in response to the US Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania in August

- The near-strike made against Iraq in late November

- Operation Desert Fox in December

- The ongoing confrontation in the Iraqi no-fly zones.

All of these operations were conducted, not to defeat a military opponent in the field, but to influence an opponent's behavior. They were usually the result of a failed or blocked diplomatic effort, treaty, or armistice. All were made against militarily weak opponents, using weapons that allowed the U.S. to pick targets precisely. All, with the exception of the operation over Iraq's no-fly zone, were short, violent actions with no friendly losses. Each action started with missile strikes, predominately Block III BGM-109 Tomahawks. Other guided weapons, including AGM-88 HARMs, AGM-130s, and Paveway II/III laser-guided bombs (LGBs) dominated both the numbers and the tonnage of weapons dropped. Newer, fifth-generation guided weapons (GPS guided), like the GBU-29/ 30/31/32 JDAM, GBU-36/37 GAM and AGM-154A JSOW saw limited use, in some cases rushed into service. Some other new systems were also used. These included the F-14 "Bombcat" (equipped with an AAQ-14 LANTIRN targeting pod), B-1B Lancer, B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, the AGM-130, and CBU-97 with the Wide Area Munition all saw their combat debut.

In addition to hardware, a number of new and improved organizational ideas were tried as well. Carrier battle groups, surface action groups and submarines had a major part in strike operations, since only the Navy had Tomahawk shooters. The USAF Air Expeditionary Unit organization was tested and some useful ideas proven.

Also, a high proportion of the sorties were assigned to defense suppression, since an unstated goal of every operation was no friendly losses. Saddam Hussein has posted rewards for the downing of an American or British aircraft and an even larger one for the capture of a pilot. He's promised a show trial for any pilot captured. Another consideration was to minimize civilian losses, which affected not only the targets chosen, but the weapons used and the route of an attack. Political leaders and the American public, as a result of our military superiority and precision weapons, expect 100% success. Airpower though, as a tool of political coercion has been largely unsuccessful.

Unfortunately, it is ironic that with such overwhelming force and precision firepower, the results have not been clearer. While we can take BDA photographs of an enemy's installations, it's harder to assess the damage to his morale and intentions. The nature of the targets meant that their military utility was often secondary to their political value.

The Bin Laden Retaliatory Strikes

Early on August 7th, 1998, two near-simultaneous terrorist truck bombs heavily damaged the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Embassy security in both cases limited damage to the embassies, but casualties were still heavy, mostly to local civilians. The attacks showed consider-able sophistication, occurring within minutes of each other at distant locations.

The early arrest of several suspects by various nations established the responsibility of the Osma Bin Laden terrorist organization. Bin Laden is a new breed of terrorist leader, a citizen of an American ally with vast financial resources and a transnational network.

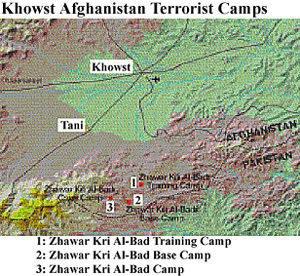

Khowst Afghanistan Terrorist Camps

Khowst Afghanistan Terrorist Camps

Bin Laden has a well-established and publicly declared policy of financing and supporting anti-Western terrorist efforts. It was quickly determined that his primary headquarters and training base was then in Afghanistan. Addi-tionally, information "obtained" from the suspects indicated that a debrief/washup would be held at Bin Laden's headquarters a few days after the attacks.

Combined with earlier work by US intelligence organizations, this presented a unique opportunity for a rapid US response. The targets were well understood from the U.S. effort to support the Afghan Mujahedin in the 1980s. Bin Laden's headquarters, training centers, and logistical facilities were all targeted.

Also selected was a suspected chemical weapons plant in Sudan. Its connection with Bin Laden was based primarily on financial support, though a single soil reconnaissance was accomplished, but not conclusive. In the end, the plant was placed on the target list by the National Security Council (NSC) staff. BGM-109 Block III Tomahawks were the only weapons used in these strikes. These weapons combined GPS/ INS guidance with Digital Scene Matching terminal guidance. They had either the new 1000 pound-class reactive titanium warhead with incendiary effects or a submunition dispenser. Some of the missiles may have been fitted with a one-way satellite status data link.

Early on August 13th, 1998, just under 100 TLAMs were launched. Five ships and a nuclear submarine of the U.S. 5th Fleet conducted the launches, and the missiles were synchronized for a time-on-target attack. The Afghanistan-bound TLAMs had to overfly Pakistan, which was not notified in advance. Only one missile failed, landing in northern Pakistan. Contrary to initial press reports, it caused no damage or casualties.

The Sifa Pharmaceutical Plant in Khartoum, Sudan was completely destroyed, with minimal collateral damage or casualties. There was, however, massive political fallout. The NSC nomination of the target appears to have been in error. The chemicals at the plant could be used to make weapons, but also had wide civilian uses, and the plant was a primary regional source of pharmaceuticals. The Afghan strikes were much more successful, with all of the targets hit and in many cases heavily damaged. Significant personnel casualties were inflicted, including members of Bin Laden's leadership. Bin Laden was present, but apparently was not injured. The immediate goals of punishing Bin Laden and disrupting his organization were achieved. As a result of our attack on Afghanistan, his organization is moving to Bangladesh. Long-term though, Bin Laden is still at large, and still has a bad attitude about the West. Call it a "tactical victory."

Operations Against Iraq

F/A-18s on board waiting before Desert Fox (US Navy)

By the Fall/Winter of 1997/98, the UNSCOM Mission mandated as part of the 1991 Desert Storm cease-fire was failing. Inspectors were finding evidence of WMD research and production - far too much evidence! They were also routinely blocked and frustrated by the Iraqis, who at the same time claimed they were in full compliance with the UN requirements. This first crisis resulted in Operation Desert Thunder. Based around two US carrier battle groups (Nimitz and George Washington), with international support, the operation was called off at the last possible moment because of an agreement brokered by the UN Secretary General.

Over the next ten months UNS-COM inspectors tried to fulfil their mission but were blocked more than before. Internal debates within UNSCOM reignited an international crisis. The final UNSCOM report, and the expulsion of the inspectors in the fall of 1998, caused a quick replay of Desert Thunder.

This time, the striking force was based around USS Eisenhower, with 129 Air Force aircraft (98 combat aircraft and 41 support planes). This included seven B-52Hs with AGM-86C CALCMs at Diego Garcia and four B-1Bs in Bahrain/Oman. Ground forces included a brigade from the 3rd MID (Fort Stewart, GA), Patriot batteries (Fort Bliss, TX), and Special Forces teams from the 5th SFG (Fort Campbell, KY). Additional aircraft were to be sent, including F-117s and F-16CJs, with the British also reinforcing their air and naval forces.

Three Joint Standoff Weapons (AGM-154 JSOW) are staged in one of the many weapons bays of USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70). Vinson's air wing first employed the JSOW during combat over southern Iraq on Jan. 25, 1999. Chiefly used against air defense sites, parked aircraft, airfields, port facilities, light vehicles, and refinery components, JSOW is a low-cost, launch and leave weapon that reduces the exposure of aircrews to hostile missile and antiaircraft artillery fire. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer's Mate Airman Jose Cordero)

Three Joint Standoff Weapons (AGM-154 JSOW) are staged in one of the many weapons bays of USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70). Vinson's air wing first employed the JSOW during combat over southern Iraq on Jan. 25, 1999. Chiefly used against air defense sites, parked aircraft, airfields, port facilities, light vehicles, and refinery components, JSOW is a low-cost, launch and leave weapon that reduces the exposure of aircrews to hostile missile and antiaircraft artillery fire. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer's Mate Airman Jose Cordero)

Once the decision to attack was made, the operation was mounted quickly, since with the UN inspectors gone Iraq could quickly disperse its WMD assets. On Saturday, November 21st, President Clinton ordered General Zinni, Commander-in-Chief Central Command, to launch airstrikes on selected targets in Iraq. The plan was to start with an CALCM strike launch from B-52s, followed by Tomahawks and manned aircraft from the carrier and land bases.

Unfortunately, the takeoffs from land bases were probably detected and reported to the Iraqis. This resulted in a last-minute announcement of concessions by the Iraqi ambassador in New York City. With just minutes to spare, the aircraft were recalled and the missile launches aborted. Because of the sudden recall, the mission was nick-named "Operation Dry Heave" by the personnel who took part. Despite concessions and reassurances by the Iraqis that they would comply, they never allowed UNSCOM inspectors back in to resume their mission. Final diplomatic efforts ended in late December, and military action seemed imminent. The November deployment was restarted, with the Enterprise and Carl Vinson carrier battle groups replacing Eisenhower. A short (3 days, 4 nights - 70 hours) series of strikes was planned, designed to hit previously identified WMD, C 3 I, and "Leadership" targets, in addition to fielded forces (mostly air defense). Precision-guided munitions were used almost exclusively, both to ensure hits and reduce the chance of collateral damage.

Operational security for the strikes was a priority. Because of the risk of "telegraphing their punch" again, land-based USAF units would not be allowed to participate until the second night. Not only were initial flights from foreign land bases prohibited, but even those from within the continental United States! The initial wave of attacks would all come from U.S. Navy assets at sea, well away from prying eyes. The eventual USAF and RAF missions originated from Diego Garcia, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman, so that Saudi Arabian involvement would be minimized.

The strikes, known as Operation Desert Fox, began on the night of December 16th. About 200 Tomahawks were launched from ships and subs, followed by seventy manned sorties. Surprise was complete, and the only enemy air defenses active were local AAA. The Iraqis were evidently waiting for word of the attack again, but it never came.

On the second night, two separate six-plane waves of B-52s launched CALCMs, followed by more Tomahawks. That same night, two B-1Bs made their combat debut, a laydown strike with 54 Mk82 500 lb. bombs each on Republican Guard barracks [Ed. Note: Aieeeee!]. There was no fighter or SAM activity, again only local AAA. On the third night, December 18th, Carl Vinson arrived in the area and began combat operations. More TLAMs and CALCMs were also launched. Again, there were no fighters or SAMs used in Iraq's defense. Attacks on the final night were made first by still more Tomahawks and CALCMs, then conventional aircraft. This was the final chance to hit "bottom of the list" target and make restrikes on early targets, based on BDA. Again, the strikes were opposed only by light AAA.

Operation Desert Fox lasted 70 hours, striking over 100 targets. A total of 330 TLAMs, and 90 CALCMs were launched, along with 325 strike missions, and more sorties in support. No aircraft were lost. Besides the use of B-1Bs already mentioned, it was the first combat use of the LANTIRN-equipped F-14 "Bombcat," the first use of the new-model CALCM (Conventionally armed ALCM with a 2,000 lb.-class penetrating warhead), and the debut of women flying combat missions (an F/A-18 pilot on the first night). Operational surprise was so complete that the brittle Iraqi air defense network could not even begin operations. SEAD aircraft had little do in this operation.

Desert Fox will go into the history books as the lowest-cost operation in US history. It was so successful and one-sided that it may give the US public and their leadership unrealistic expectations about future combat operations. Worse though, allied forces expended a lot of ordnance, lowering war stocks of PGMs to dangerously low levels. This has already proven to be a problem in the Balkans.

Saddam lost militarily and perhaps tactically, since his ability to produce WMDs in the short term has been seriously reduced. In the long term, he is still in power, and his basic abilities and intentions are unchanged. His political stock may have actually improved with his radical neighbors. Information from the arms control community indicates that his R&D effort is basically complete, and that duplicate sets of design data are secreted all over the country.

However, Desert Fox did hurt Saddam's ability to command his military forces and strike back at Coalition forces. Many political targets and symbols were hit, which may affect his standing with his own people. Because so many air defense and C 3 I sites were hit, Coalition forces have been able to operate more safely over Iraq.

The No-Fly Zone Confrontations

Following Desert Fox, Coalition forces resumed their enforcement of the two No-Fly Zones. Almost immediately though, Saddam Hussein declared the No-Fly zones illegal, and said that aircraft that violated Iraqi airspace would be shot down. His attitude is understandable, given that the Coalition had just bombed much of his country again. His efforts to defend Iraqi airspace, though, were sporadic and ineffective. A war of attrition broke out, starting on December 20th and continuing to this day. The confrontations began when Iraqi SAM batteries began to lock up Coalition aircraft in the No-Fly zones. The normal allied response was launching a pair of AGM-88 HARM missiles, which would silence the radar. This would be followed up by a pair of GBU-12 500 lb. LGBs on the radar van (which permanently removed it from service), and additional GBU-12s dropped on the SAM launchers as required.

Effectively, every time the Iraqis lit off a SAM radar, the entire site was obliterated. There have been over three dozen such incidents, with no Allied losses. On January 5th, the Iraqis changed tactics. A total of 14 Iraqi fighters under positive GCI control made runs into the Southern No-Fly Zones. Two pairs of MiG-25 Foxbat-Es actually illuminated pairs of F-15Cs and F-14Ds. A total of 3 AIM-120 AMRAAMs, 1 AIM-7M, and 2 AIM-54 Phoenix (first combat use!) were launched, but none appeared to hit. One MiG-23 did crash from fuel starvation while trying to land. The operation appears to have been an attempt to lure US aircraft over SAM/AAA traps. It has been repeated since then, but on a much smaller scale. Thus far, no air-to-air kills have been scored on either side. The Iraqis then started a "Cat and Mouse" game, using SAM radars and fighters as bait. The US has responded with the first combat use of the AGM-130 (a powered GBU-15) and AGM-154A JSOW. These allow aircraft to engage at longer, safer range. The Coalition has also responded by expanding the ROE, allowing engagement not just of the offending site, but "vertical engagement" of the site's chain of command. JSOW has been a particular success, with over two dozen successful launches, with a perfect hit rate so far!

There have been no allied losses to date, although Iraqi losses in materiel and troops have been heavy. There has also been one accident, when on January 25th an AGM-130 hit civilian housing near the Basra airport, killing 11 people.

As of late March, over 100 incidents have occurred in the No-Fly Zones since Desert Fox. More ordnance has been dropped since December 20th than was used in Desert Fox. Over 33% of Iraq's air defense assets have been destroyed, and others have been withdrawn from the No-Fly zones. Continued aggressive allied tactics have made this campaign bigger than any since Desert Storm.

Large Baghdad Target Photo (slow: 149K)

Jumbo Baghdad Target Photo (slow: 186K)

What's Next?

This has been the busiest "non-war" period in the history of U.S. airpower. It has validated many new expeditionary warfare concepts and weapons systems. Operations tempos are very high - which have directly affected retention and modernization. Warstocks have been depleted, and have affected operations in the Balkans. Airpower can buy time for politicians and improve the local operating environment, but it can't change a dictator's mind and it's no substitute for long-term foreign and national security policy. Our massive military superiority over many of the world's dictators and strongmen will continue to encourage politicians to use airpower as a diplomatic tool. However, it seems to have had little real effect on long-term issues. Meanwhile, keep an eye on the Balkans…We have!

BT

Back to The Naval Sitrep #16 Table of Contents

Back to Naval Sitrep List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Larry Bond and Clash of Arms.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com