Born in London in 1936, Christopher Duffy experienced war as a child when in 1941 a German bomb missed an aircraft factory and hit his home. After completing his higher education at Oxford, Duffy faced a career choice between pharmaceuticals or history. In 1961 he became one of the few professors in the new Department of Military History at Sandhurst. Duffy does not consider himself a natural university academic and admits that Europe before the French Revolution is most interesting to him. His noblesse oblige and wonderful wit help characterize Duffy, in sentiment and spirit, as one of the last members of the ancien regime.

Born in London in 1936, Christopher Duffy experienced war as a child when in 1941 a German bomb missed an aircraft factory and hit his home. After completing his higher education at Oxford, Duffy faced a career choice between pharmaceuticals or history. In 1961 he became one of the few professors in the new Department of Military History at Sandhurst. Duffy does not consider himself a natural university academic and admits that Europe before the French Revolution is most interesting to him. His noblesse oblige and wonderful wit help characterize Duffy, in sentiment and spirit, as one of the last members of the ancien regime.

In this, our eighth interview of outstanding French Revolutionary and Napoleonic authors, Dr. Christopher Duffy shares his thoughts about research, teaching, and what drew him to the particular areas of history for which he is now regarded as the English-speaking expert.

John Keegan, a colleague of Christopher Duffy at Sandhurst, mentioned Dr. Duffy twice in his seminal work The Face of Battle (1976). In a section called "The Deficiencies of Military History", Keegan argued that although exploring the combatants' emotions is an essential element in the "truthful writing of military history, we are still left with the problem of how it is to be done.... The almost universal illiteracy, however, of the common soldier of any century before the nineteenth makes it a technique difficult to employ. Dr. Christopher Duffy, by heroic labour among little-known Prussian and Austrian archives, has pushed the technique backwards into the eighteenth century..." (p. 32).

Keegan further noted a very interesting field experiment where "Christopher Duffy, who was lucky enough to spend some weeks teaching Yugoslav militia the elements of Napoleonic drill for a film enactment of War and Peace, described to me the thrill of comprehension he experienced in failing to maneouvre his troops successfully across country Žin line' and of the comparative ease with which he managed it Žin column', thus proving to his own satisfaction that Napoleon preferred the latter formation to the former not because it more effectively harnessed the revolutionary ardour of his troops (the traditional Žglamorous' explanation) but because anything more complicated was simply impracticable" (page 34).

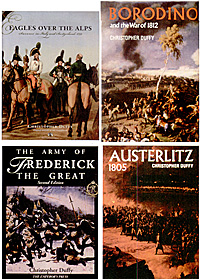

Duffy has nearly a dozen published books in his 40-year career, some considered "classics" or the authoritative source on the subject. These include Austerlitz 1805 (1977, reprinted 2000); Borodino and the War of 1812 (1970, reprinted 2000); The Army of Frederick the Great (1974; new edition by The Emperor's Press 1996); Friedrich der Grosse und Seine Armee (Motorbuch-Verlag); Eagles Over the Alps: Suvorov in Italy and Switzerland, 1799 (1999; see excerpt and review printed in Napoleon #15); Fire & Stone: The Science of Fortress Warfare 1660-1860 (1975, reprinted 1998); The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great, 1660-1789 (Siege Warfare Volume II, 1985); The Army of Maria Theresa: The Armed Forces of Imperial Austria, 1740-1780 (1974, reprinted 1994); The Military Experience in the Age of Reason (1987, reprinted 1997); Russia's Military Way to the West: Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power 1700-1800 (1981, reprinted 1994); and Confrontation: The Strategic Geography of NATO and the Warsaw Pact (written under the pseudonym of "Hugh Faringdon", 1986).

Duffy learned French in school. In order to do research in the Austrian archives he taught himself German, which led to Dutch, Danish, Swedish, and Russian. He is now working on Czech and Italian.

Duffy was Senior Lecturer in War Studies at The Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst until his retirement in 1996. He notes that what he taught at Sandhurst would not be considered military history. Rather, his classes dealt with the background and origins of, say, armored warfare in direct relation to modern military doctrines and practices, information of immediate use to the young army officers who attend Sandhurst. Ironically, it was after he left Sandhurst that Duffy began teaching military history--to students with civilian backgrounds--at De Montfort University in Bedford, England, as Research Professor in War in History.

What do you teach at De Montfort?

DUFFY: I run a postgraduate seminar of between ten and fourteen weeks called The Theory and Practice of War. I use the first three weeks to give students a grounding in military technology and structures and language. The difference between tactics, operations, and strategy, for example. What you mean by a division and a corps, the structure of military ranks. The basic military things that most civilians do not know.

By the end of the course you could have somebody who started the seminar series totally ignorant of military affairs, and turn them loose on a book of a campaign and they'll come back with a good cogent command of it, which would be beyond the reach of another civilian historian who has not had this basic grounding. I must say I'm very pleased with the way it has worked out.

My students almost invariably are graduate students or professional people with graduate type experience and qualifications, working in their own time after a busy working day. They're very serious, and they're coming to you not because it's required, but because they truly want to.

You were a young boy when World War II was in progress. Do you remember anything of that period?

DUFFY: I remember a very great deal. I think a very important point is the generation I came from. I'm a very close contemporary of my friends David Chandler and John Keegan. There are only two years between us altogether, that particular spread. We all grew up during the war at a most formative stage of our lives, where we assumed that war was a natural state of humanity so there was nothing strange about being at war. The thing that did seem strange was the coming of peace in 1945. We asked ourselves, "What do people do in peacetime?"

Is there anything from that period of World War II that really stands out, that really made an impression?

DUFFY: Many things. Our house got a direct hit from a bomb, a small incendiary bomb, which could have caused a catastrophe, but it penetrated a roof, hit the carpet in the bedroom, and bounced straight into a big coal-burning fireplace where it burnt itself out, blackening all the glazed tiles around it. I remember the tremendous crash from the air raid shelter in the basement and this intense white light over everything. I remember being grabbed and hastened outside, and the firemen arriving. I still see very vividly the imprint of their black boots over the house. They'd knocked things over and left great dirty footmarks everywhere. They made much more impression than the actual bomb did.

You mentioned that you chose a "military special" in your third year at Oxford. What was it that drew you to military history?

DUFFY: Partly family tradition. Nearly all my folks had joined the army in Ireland in the 19th century. They went abroad to places such as the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny, and the tales of those two wars were very much part of family life. My mum and father remembered talking to people who had been to those wars and they were recent wars in those times [1940's]. My grandfather particularly had a great influence on me because he worked as a civil servant in Woolwich Armoury in London that was the main arms manufactory at that time. Nearly all my folks, when they left the army, became civil servants working in Woolwich. It was a natural progression; this work was arranged for them when they ended their military service.

Woolwich is just outside London. It is and was littered with cannon, shells, bombs, and military museums. My grandfather used to take me around to these and talk about what happened in the Crimea. My parents were very cunning because I was and am very bad at mathematics. If I did extra work on mathematics as a treat I would be allowed to go to the military museums.

I've done some research recently on the two great-grandfathers who served at the time of the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. The character of one is described as "intemperate;" the other was court-martialled four times, slowly made it up again to corporal after each disaster, and was busted down again. I'm very pleased, because I can blame it all on genes, heredity or something.

What was your route to Sandhurst?

DUFFY: I had no great inclination to be a teacher right off. I spent three years research mainly working in the War Archives in Vienna. Almost as soon as I got my doctorate I was offered a job at Sandhurst in the new Department of Military History. It was set up in 1960, the year before.

Sandhurst, the military academy for British Army officers, did not have a specific department of military history until 1960?

DUFFY: They had a very primitive form where it was taught by serving active officers up to that time. The department was set up by Brigadier Peter Young, Military Cross, Distinguished Service Order with double bar, who was a brilliant, daring, utterly fearless commando leader in the Second World War and then became a colonel, I believe, in the Arab Legion.

And he was an extremely picturesque character, a genuine cavalier. He liked women, he liked drink, and he was a super, super guy. He wasn't one of these prissy kind of academics. I liked him, and he saw something in me, I don't know what, but we got on tremendously well.

Did he become your mentor?

DUFFY: Very much so, and he appointed John Keegan and David Chandler a year or two before me. At that time the academic staff at Sandhurst was very small, and we organized the military officers to teach military history. They did most of the teaching and we prepared material for them, made their timetables, and gave the central lectures.

You mentioned working on your Ph.D. in Vienna. What was the subject of your dissertation?

DUFFY: It was the Austrian Field Marshal Maximillian Browne. He was a leading commander in the army of Maria Theresa in the 1740's and 1750's. He survived into the second campaign of the Seven Years War, in which he was mortally wounded.

What drew you to that particular era?

DUFFY: I don't know. I think, like lots of people who are asked about this, the answer is, "We like the hats." The tricorn hats. I liked the fashions. I think there's something magical about it, a bit of a fairy tale about it. Now, no serious academic would use these terms, and I don't count myself as a serious natural university academic. I count myself as a sort of romantic academic as it were, who does things for the fun of it. It was the ambiance; the people didn't care what other people thought about them. They liked the fashions, the music, and the architecture. It all seemed to hang together in a very harmonious way. It was not too barbaric, yet not too modern.

Is this the division between the Age of Reason and the birth of the modern era?

DUFFY: Yes, things were on the cusp as it were. From about 1740 people began to think along modern lines. You can't actually relate directly to Prince Eugene of Savoy personally. He seems a little more remote somehow, but from the 1740's and '50's we can actually identify very closely with what people were doing and thinking. Yet at the same time you don't really have bureaucracy and central control and technology exerting control, which they began to do during the 1780's.

I'm very struck, for example, by handwriting. In the 1740's, '50's, and early '60's you find people generally speaking, certainly in Austria, writing great letters with big spaces between lines, and flourishes. Come to the end of a page, run out of paper, they'll write up the side of it, around all the four sides of the letter, that kind of thing. Very often even the official clerks would put drawings or embellish capital letters with lots of calligraphic fireworks displays. By the 1780's you find already the spirit of the machine age and bureaucracy creeping up. Writing becomes much more cramped. A very very distinct change, certainly in central Europe. They begin to become much more bureaucratic in their mentality, you can see it creeping up.

So there is less artwork involved, and more function?

DUFFY: Yes, the functional side is taking over very strongly towards the end of the 18th century.

England has a rich history and heritage from that period. All of that is sitting right there around you in England, yet you chose Austria. What was the reason?

DUFFY: Two reasons. The first one, I'm very much of Irish ancestry. I'm not a republican; I'm very much against republicanism and nationalism. I have no time for this side of the Irish activity, but I was and am very interested in the history of the Wild Geese, the men and officers who took service with Catholic armies. Some of the most important of these people went to Austria. Also, I very much like central Europe and Austria, Vienna in particular, and these things coming together made the idea of studying in Vienna very attractive.

Now you're sitting in England with all the archives at hand, but it's difficult business getting at them. We've never had a dedicated war archive as such. I suppose nine tenths of relevant material is scattered in private hands, accounting record offices, various libraries, and so forth. At each of which you have to negotiate for access, and travel is very expensive.

It is very hard work doing military research in England. In the Continent you have for many years, in many countries and states, a tradition of centralizing the archives. From the time of Prince Eugene in Austria, not only have they centralized all the archives of military interest in the War Archives, but the royal archivists themselves have systematically brought in all private collections which come on the market of military interest. Say a prominent military family dies, the War Archives in Vienna has for centuries made it its business to try and get hold of this man's private papers. So in addition to bureaucratic centralized archives, you have big holdings of private material, which in Britain would be in private hands or local record offices.

So the irony is that it is easier to do research in archives on the Continent?

DUFFY: Very much so. I'd put it at least five times easier.

How did you become interested in the Napoleonic era?

DUFFY: I don't know why I did it or why I still do it. I kind of drifted into it, mainly because of having, in the course of my other work and travels, come across material and places of relevance to that. I always found the Russian army very attractive because of the extravagance of the Russian character. They never do things by halves; they produce interesting people, do interesting things, most of which are pretty crazy and far out. I think you usually find, not always, that there's a big Russian element in what I've done on the Napoleonic period.

I've got no emotional tie to this period, and I do find Napoleon absolutely repulsive.

As a person, or as a leader?

DUFFY: I dislike Napoleon as a person, but if possible dislike Wellington still more. I dislike the things he's done to the world. I think at the moment Britain is still struggling against the centralizing legacy of Napoleon. Unlike Hitler, you can say he did have a constructive side to him, but at the cost of a great deal that was individual and distinctive about the peoples of continental Europe. This was just the first of a series of breaks in continuity.

Are there any positive aspects to Napoleon? Why does he seem to be such an attractive person to many Americans?

DUFFY: The main thing about Napoleon is that he thought big. He tended to think on a bigger scale than his opponents, of which the evolution of the corps system was only one manifestation. He was outthinking his opponents very much at any given level--he was thinking that little bit higher than his enemies were.

In addition we have his great ability to select out of a mass of detail that which was critical and important. Not that the other detail wasn't important, but he was able to identify what really was important and what was worth having.

I think that together with his tremendous egotism and arrogance this gave him the edge over his opponents. I think this is really one of the reasons he appeals so much to Americans, and very often a European will be put off by a problem because the first thing we look for are the difficulties. We think, "Well, this is not really worth the effort, we might be lucky and get away with it, but let's carry on with what we're used to."

Americans, as I see every time I come to the States (I really love the States and Americans), they start off with this can-do attitude and they overcome problems by sheer optimism, obviously not caring about risks of failure or minor blunders on the way. They pour on resources and they pour on the optimism the same way as Napoleon poured on his firepower on the battlefield. And that so often leads to success, whereas a more conservative-minded person would look first at the problems and be deterred.

You wrote a book about Russian Field Marshal Suvorov. Are there any other characters of the Napoleonic period that you really enjoy?

DUFFY: No, I think only Suvorov. To me he is a very good guy. He comes across so often in descriptions as a kind of mad, crazed peasant, as he was to some degree. He was also highly educated and a deep-thinking man. I am fascinated by this juxtaposition of his charismatic leadership, his understanding of the mentality of the Russian soldier, his deliberate playacting, plus thinking very deeply about what the issues of war at that time were. To him, war was basically a contest of value systems. I don't think Wellington, for example, thought of things in that way.

What is your perception of the Duke of Wellington? One British author noted that Wellington's comment about Napoleon "not being a gentleman" could be applied equally to Wellington himself. Do you have any opinions about Wellington?

DUFFY: Yes, I must say, of the two, I prefer Napoleon as a person. Wellington I think had this fundamental coldness in his heart. Okay, he could weep when he met casualties, sometimes, but basically he was a cold-hearted bastard. He is very largely responsible for what became the image of a type of English gentleman: reserved, aloof, cold, soberly dressed, which did not exist before the time of Wellington. The idea of the upper-class Englishman of the 18th century was a bluff, bombastic, devil-may-care character who didn't care what others said or thought. They behaved fairly extravagantly. But Wellington set the new standard of the English milord: cold, reserved, soberly dressed.

As an expert on the Seven Years War, what do you feel are the differences between Frederick the Great's style of warfare and Napoleon's?

DUFFY: I think on the mechanical side you have very clear continuities between the two periods. New, more efficient artillery, Prince Joseph Wenzel Liechtenstein's Austrian system of the 1750's leading directly to the French Gribeauval system which armed the Revolutionary and early Napoleonic armies. The origination of the divisional system in the Seven Years War leading to the creation ultimately of Napoleon's corps system.

I think on the structural and mechanical side they have a very distinct continuity, but on the issue of what wars were about, the motivation behind them, the motivation of the soldiers, the consequences for states and society of defeat were much more far-reaching in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic period than they were in the middle of the 18th century.

Do you feel that warfare became more modern?

DUFFY: Oh yes, I think it's a very distinct thing. Generally speaking, before the French Revolution if a king conquered a province for himself, he'd be very careful on the whole to respect local sensibilities, laws, institutions, and religious practice. Things which the people valued he would probably leave alone, not because of humanity, but because he didn't want any trouble. So for nine tenths of the people whose political master changed on top, I think life would go on as normal in the middle of the 18th century. The Revolution and Napoleon changed all that: They began to overthrow laws, institutions, political structures; they centralized. They didn't care what people thought of them. They imposed their will by brute force.

Getting back to the books you have done on the Napoleonic era, you mentioned you were thinking of redoing Austerlitz. Is this because you have discovered new information, or you've reevaluated your work?

DUFFY: I think, as any author will tell you, he is always very dissatisfied with his own work. The moment it's beyond recall, gone to the printers, you begin to rethink things. You always say, "Gosh, I wish I'd put that rather differently." The course of time accentuates that. You say, "I overstressed this, I didn't stress that sufficiently." Then you have the discovery of one or two, perhaps a few, new sources. Then you have other people writing on the same subject and you find they modify your ideas and correct you on points of detail. They might have new approaches which you've got to hoist on board. All this after, at the very least, ten years builds up a great desire to refashion your own literary past.

Is the availability of the previously unavailable Russian archive material part of the motivation?

DUFFY: It is very difficult for a British person to work in Russian archives. You really have to have connections and introductions. On the whole you will find Russian archivists much more responsive to working with American historians because of the power and prestige of the United States, than working with British or French historians. That's not to say that, particularly a young historian in his twenties, could not go to Moscow and get a good deal of material. But for an old geezer in his sixties life is too short to go through what you know is going to involve a lot of frustration.

Generally, not just the Russian material, but you do find new archive sources coming to light all the time. In the last year or two, we have the reopening of the secret Prussian state archives in Berlin, which have managed to retrieve a great amount of material from Eastern Europe, which was thought to have been destroyed in the war in 1945. There's a vast amount of material relating to the Prussians in the Seven Years War, for example, which was not even looked at when it was available to historians up to 1945.

For example, I came across the Prussian spy reports on the Austrian army before the Seven Years War. At the last moment I was able to insert a new section in my book of what Frederick got wrong about the Austrian army before the Seven Years War.

Another very fertile source for almost any period of military history are reports of foreign ambassadors. You have, for example, reports of the Swedish ambassador to Vienna in the Seven Years War which nobody has looked at. I've been able to obtain photocopies of these reports, and they stand about eight feet high. There's tremendous material there. This man talked with Maria Theresa every week and she gave him the lowdown on how she thought the war was going and what she was trying to do.

It sounds as if there is so much material becoming available that has never been touched

before that it could keep hundreds of young scholars busy for a lifetime.

DUFFY: Very very much so. A big problem is that of languages. I don't know what the situation is in the States, but language teaching in the schools in Britain is very poor indeed. Very few young British historians, let alone military historians, are capable of reading a single foreign language. This can be perhaps a minor disadvantage if you are studying the history of your own country, but I think it's a crippling disadvantage if you are studying military history because by definition you are at least dealing with foreign countries, as allies and as enemies. Unless you have the means of looking at their material in their own language you are going to end up with a very limited point of view.

Returning to your Austerlitz book, can you give us an example of something that might be different in a

new edition?

DUFFY: I'd have to take on board what Scott Bowden has written about it in his massive book Napoleon and Austerlitz. He worked very extensively in the French archives, which I have not, at least not on that particular battle. Then again, there is quite a lot of good material that has come out in the Czech Republic on this. They are the local boys, although they were not represented of course as the Czechs in this battle. Nevertheless, there's a very strong local interest in it. Some of their findings are very interesting, particularly the archaeological findings, and these I would have to incorporate in the new edition, if it does take place.

Do you have any recommendations for young scholars today?

DUFFY: I always find, if a would-be scholar comes to me and says, "Could you suggest a subject that I should work up?", I tend to give them a very cold reception. My belief is, if you are truly dedicated to military history, you should very early on have a very clear direction for your interest and be prepared to follow up those interests. You should not just have those interests suggested to you. You must search them out for yourself.

I think a very great danger is that military history has become too easy, too accessible. So many good books available, so many opportunities which certainly did not exist in my early days or those of David Chandler and John Keegan. We had to make do with what we could actually find, which was not at all easy. You have many courses in military history in universities. This in a way can make it too easy for people to drift into the subject and take it up to a certain level, then hit a very definite ceiling where they stick. I think, in a way, military history should be made harder to study than it is now, to make only a dedicated person stick with it. I'm very firm on that opinion. That will not make me popular, but I'm very convinced of that.

What is your opinion of studying military history as an avocation instead of a career?

DUFFY: I think a very big issue is that of the civilian studying military history. The difficulty of this--the very first subject when moral issues come up which John Keegan addresses very directly in a lot of his books--is how am I entitled as a civilian to study military history? I think we can extend the word civilian to many serving soldiers and officers at the present time, the great majority of whom know the mechanics of their training, but would probably never actually put them into practice in combat.

I won't say that civilians, or what you might call civilian soldiers, are not justified in studying military history, but they've got to address it in a very serious, systematic way. Learn the language, the terminology in a very professional way so at least they can, to some degree, make up for their civilian backgrounds. Above all I think they should be very chary of passing easy judgments on what seem to be mistakes and blunders by military men.

There seems to be a tendency among some writers to label generals "incompetent" or "stupid" when the authors have the advantage of hindsight. But put someone in a situation where they only have limited information and limited intelligence and a limited field of view, and the one correct

decision is not so obvious.

DUFFY: And massive responsibilities extending perhaps beyond the possible defeat of their army to the overthrow of their own state, which might perhaps be in a very shaky condition. They simply have to be cautious to avoid to the overthrow of their entire state. This is so often neglected if you just look at the tactical side.

Is contemporary military background a big advantage?

DUFFY: You can get men and women with professional military backgrounds who are actually not very good at writing military history because the temptation and danger on their side is not realizing the differences between modern warfare and military people and past warfare and military people. They think their active military experience gives them a kind of magic bridge into the past. It's a great help, but it's not this magic bridge that they might imagine.

It can help them with the mindset, but it does not tell you anything about the period?

DUFFY: They tend to think very much in modern terms, not all of them, but we're looking at the past. Another relevant fact is just how dangerous war is. Combat is unbelievably dangerous to the extent that, in an active general war of any duration, your infantryman is not going to survive unless he is very, very lucky. Perhaps the best thing that could happen to him would be to be wounded or captured early in a war, so that he could survive. The odds are he will not survive intact, or indeed alive. This by definition will cut down the number of military men available to write about military history from the perspective of active combat, because the odds are they will not survive active combat of any duration.

So even on the Peninsula, where a Napoleonic British soldier might be in many successful battles, because casualties occur in every one of those battles, his odds of survival were getting slimmer and slimmer?

DUFFY: I think his chances were much better in that war, probably, than they were in World War II or World War I because combat was relatively infrequent, whereas you can say combat, or at least danger, was often continuous in the two World Wars. In the British army I think of the tactical commanders who went to Normandy in June of 1944; only a handful survived until the surrender of Germany. All the rest were killed or wounded.

Can you elaborate on your ideas about the differences between the professional historian versus the amateur historian?

DUFFY: I think there are three kinds of historians. You have the amateur who does it from a love of the subject. You have the amateur who is lucky enough to do it full time. I would call that person the "amateur professional" who can do it full time, but still does it for love of the actual work and subject. Those two I would class together, the amateur and the amateur professional.

The third class, which is increasingly very large, are the career historians, who do it simply because that happens to be their work. They could be just as happy or unhappy in the law or medicine, and they do in fact have a distinct lack of personal commitment to the subject, but they are very skilled at meeting demands of the work in terms of ticket-punching careerism, bringing out X number of books, articles, and papers every five years. And increasingly in Britain and the United States, universities measure achievement by these statistical yardsticks. How many books did you bring out? Will these people spend their own time and own money in pursuit of the subject without this incentive? You'll find they almost certainly will not. To them it is basically a career, so I do make this distinction between the career historian, and then the amateur and amateur professional on the other side. There is a very clear difference.

Do you feel the amateur historian has something to contribute?

DUFFY: Oh, absolutely yes. Very very much so. I think the only difference between the amateur and the amateur professional is the professional generally has more time and facilities at his disposal.

Military history almost uniquely bridges the gap between the amateur and the professional, in a way which I can't think any other branch of history does. In military history I think you have a merging of the two in their outlook, the kind of people they are, that their standards are much more closely related than you will find in any other branch of history.

Don't think that certain people lucky enough to be a so-called professional in the subject, that they are therefore any happier in it, or more successful in it than the interested amateur. The word "amateur" means "a lover of a subject" and that's the most important thing of all.

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #16

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct