According to Reuters news service, the attending experts said they were holding their meeting encouraged by intense public interest over a DNA test which recently settled one of French history's enduring mysteries, and proved that guillotined King Louis XVI's 10-year-old son died in jail in 1795 and was not spirited to freedom by sympathizers.

Interestingly, despite the recent surge of interest in the murder theory, rumors of foul play began even before the deposed Emperor of France was dead, in part circulated by Napoleon himself. Napoleon believed that Sir Hudson Lowe, the Governor of St. Helena charged with the supervision of Napoleon's captivity, deliberately contributed to his declining health by the imposition of many trivial inconveniences and restrictions upon the Emperor's activities -- and that the particularly barren location of the Longwood House, residence of Napoleon and his retinue, was selected to hasten his demise. In addition, the climate of equatorial St. Helena was believed to be somewhat malignant -- some at the time attributed the weather as the cause of the island's high rate of hepatitis.

Napoleon, meanwhile, waged a fierce war of words with his "jailer" designed to shame the British into improving his living conditions. While his petty wrangling with Governor Hudson Lowe often approached the comic, Napoleon gamely attempted to win popular sympathy by casting himself in the role of a martyr. Napoleon felt quite confident that history would regard his treatment on St. Helena not as a mere exile or imprisonment, but rather as a slow and deliberate execution. If Ben Weider is correct, Napoleon's suspicions were all too true, but not quite in the way he imagined.

Napoleon died three months short of his 52nd birthday on 5 May 1821 after what appeared to be a long illness. The diagnosis by the attending physicians who performed the autopsy was that Napoleon died of stomach cancer.

The Emperor, thinking mostly of his son and showing both a faith in the advancement of medicine and a prescient recognition of heredity as a factor in disease, ordered that his stomach be removed from his body and preserved in a sealed jar, with the hope that whatever killed him might someday be known to science and made curable. Ironically, the contents of that jar -- which sadly could do nothing for his son, who died prematurely at the age of 21 on 22 July 1832 of tuberculosis -- may instead hold irrefutable proof of Napoleon's murder.

Arguments have raged over the diagnosis of cancer from the very start. Shortly after news of Napoleon's death in 1821, pamphlets appeared in Paris attacking the cancer thesis and some went so far as to argue that Napoleon had been poisoned. While contemporary Bonapartists may have found it emotionally unsatisfying to believe that their beloved Emperor had died relatively young and of natural causes, little evidence surfaced at the time to support their darker suspicions.

The controversy went into hibernation for many years, and seemed almost forgotten in the cataclysms of the twentieth century, when popular opinion tended to obscure the sympathetic view of Napoleon as the defining figure of his age in favor of more critical interpretations that saw in his reign the precursor of the modern dictatorship.

The evidence that re-awakened the controversy -- a "veritable time bomb" according to Ben Weider -- surfaced in 1955 in the form of the previously unpublished memoirs of Louis Marchand, Napoleon's valet (published in English by Proctor Jones titled In Napoleon's Shadow). At once hailed for its reliability and remarkable intimate portrait of Napoleon at St. Helena, Marchand's memoirs provided something else -- a detailed documentation of Napoleon's demise.

In the early 1960's, based heavily on his reading of the symptoms detailed in the Marchand memoirs, Swedish dental surgeon and amateur toxicologist Stan Forshufvud challenged the Napoleonic community in his book Who Killed Napoleon? with the provocative thesis that Napoleon had died of arsenic poisoning -- not cancer.

Marchand's second great contribution to history came in a rather amazing package -- after Napoleon's death Marchand cut and carefully preserved some strands of Napoleon's hair. Through the assistance of noted French historian Commander Henri Lachouque, Dr. Forshufvud was able to take samples -- the identity of the hairs unknown to the scientists -- to the University of Glasgow Laboratory of Forensic Medicine and the Harwell Atomic Laboratory.

Here they were tested for levels of arsenic. When the results came in showing a fairly high level of arsenic content, Marchand's time bomb fully detonated. Spurred on by what seemed to them incontrovertible evidence of a poisoning plot, Dr. Forshufvud would, in collaboration with Ben Weider, go on to publish additional works on the theory, spawning a debate that has often been personally rancorous as well as politically charged.

Interestingly, Forshufvud and Weider have also named the killer, and not the one Napoleon imagined -- a Frenchman, General Count Charles Tristan Montholon, an intimate member of Napoleon's retinue on St. Helena, is their suspected assassin. Montholon supposedly was working for the Bourbons who had been restored to power in France. Their position was still shaky at the time. Napoleon returned from his first exile on the island of Elba and easily retook the throne in 1815. Forshufvud and Weider contend that the Bourbon's motive for the assassination was to permanently eliminate this threat to their rule and prevent a repeat of 1815 by Napoleon or his followers in France.

Although Forshufvud's thesis has gained widespread popular interest around the world, many historians, naturally reluctant to accept such a dramatic revision of the record, remain unconvinced. The evidence -- the arsenic content in the hairs -- and the authenticity of the hairs has been challenged. The original diagnosis of cancer has been defended. Alternate reasons for Napoleon's death -- other than deliberate poisoning or cancer -- have also been presented. One of the more fantastic sounding propositions is the claim that Napoleon may have ingested arsenic from vapors emitted from the wallpaper in Longwood House. As with all such heated arguments, intensified by the sporadic interest taken in the issue by the mass media, it is sometimes difficult to discern if certain critiques are fueled more by disapproval of Weider's passionate and aggressive promotion of Forshufvud's poisoning theory, or the theory itself.

Without question, as the First Empire bicentennial advances inexorably to 2021 and the 200th anniversary of Napoleon's death, and as more and more historical controversies are settled by advanced scientific testing and genetic research, the pressure will build upon the French government to do the one thing that can definitively settle this fascinating final chapter of the Napoleonic saga.

As any student of the Kennedy assassination knows, governments are often extremely reluctant in taking the necessary steps in regards to exhumation when the subject is so controversial and politically sensitive. There is also speculation that because the finger of suspicion points to Montholon and not the British government, official French interest in exhuming the body of Emperor Napoleon I remains considerably low.

The sensational nature of the story, the passionate arguments it has generated, the complex technical aspects of arsenic poisoning and cancer, and the fact that all the potential witnesses are dead have made it impossible to reach a definitive conclusion. The staff of Napoleon Journal are working on a presentation of the debate about Napoleon's death, including an examination of the evidence, the counter-arguments, alternate theories, and, most importantly, why it matters that Napoleon was murdered and did not die of natural causes. We hope to complete our investigation soon and offer our readers a balanced summary.

"The quantities [of arsenic] however seem to me to be too small to draw any definitive conclusions," said Lt. Col. Roland Molinaro of the French national gendarmerie's (para-military police) main criminal laboratory. "In a modern case we'd analyze blood or urine samples. From experience, I can tell you the arsenic level in urine rises 20 or 30 times above normal levels when you eat shellfish. Did Napoleon eat seafood before his death?" he asked.

Yvan Ricordel, director of the Paris police toxicology department, said the number of Napoleon's hairs available for examination was three or four. "You cannot make a satisfactory analysis with such a limited sample. We should try again or exhume the remains," he said.

Professor Chantal Bismuth, head of the Paris anti-poison center, cautioned that arsenic was routinely used in small quantities in medicines of the 19th century. Until the examination of the hairs, it was generally assumed Napoleon died of stomach cancer but Weider says his wide girth at death disproves that. Cancer specialist Andre Tardot agrees, saying both theories might be correct. "Perhaps he was poisoned but nonetheless died of another type of cancer that was wrongly diagnosed," he said.

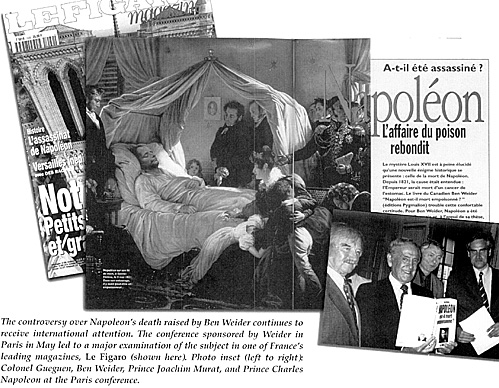

The most recent chapter in the long running controversy over Napoleon's death unfolded in Paris on 4 May 2000 at a conference held in the historic Luxembourg Palace. Canadian publisher Ben Weider, author of The Assassination at St. Helena and the leading champion of the theory that Napoleon was poisoned during his six years of exile on the island of St. Helena, sponsored a seminar involving some of France's leading criminal pathologists and oncologists. The discussion focused on the latest interpretations of the medical evidence: Did Napoleon suffer from chronic arsenic poisoning -- evidence of which Weider claims was found in strands of his hair -- or did he die of cancer as originally diagnosed?

The most recent chapter in the long running controversy over Napoleon's death unfolded in Paris on 4 May 2000 at a conference held in the historic Luxembourg Palace. Canadian publisher Ben Weider, author of The Assassination at St. Helena and the leading champion of the theory that Napoleon was poisoned during his six years of exile on the island of St. Helena, sponsored a seminar involving some of France's leading criminal pathologists and oncologists. The discussion focused on the latest interpretations of the medical evidence: Did Napoleon suffer from chronic arsenic poisoning -- evidence of which Weider claims was found in strands of his hair -- or did he die of cancer as originally diagnosed?

From the Reuters News Service Report on the Paris Conference

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #16

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct