Avid horseman, former U.S. Army Ranger [now Lieutenant Colonel

(Retired)], the biographer of Joseph Bonaparte, currently holder of an

endowed chair at the University of South Carolina, Owen Connelly has

influenced an entire generation of college students through his popular

textbooks and monographs. In this reticent, biographical interview he

explains the irony of how the Korean War shaped his career as a

Napoleonic historian. Connelly also reveals why he can write so

knowledgeably about Napoleon's problems fielding cavalry units.

Avid horseman, former U.S. Army Ranger [now Lieutenant Colonel

(Retired)], the biographer of Joseph Bonaparte, currently holder of an

endowed chair at the University of South Carolina, Owen Connelly has

influenced an entire generation of college students through his popular

textbooks and monographs. In this reticent, biographical interview he

explains the irony of how the Korean War shaped his career as a

Napoleonic historian. Connelly also reveals why he can write so

knowledgeably about Napoleon's problems fielding cavalry units.

Since 1961, Owen [whose nickname is "Mike"] Connelly has been creating his own legend in the classroom at South Carolina's major graduate

research university. The dark, hawk-like eyes and distinctive Southern

drawl, emanating from deeply within his broad chest, are as unmistakable

as his costume: a business suit accessorized with a string tie fastened

by a sterling silver and turquoise bolo, and peeking out below his

pant-cuffs, the sharp points of comfortably-worn Western riding boots.

To thousands of students and professors at colleges and universities

elsewhere, Professor Connelly is the faceless author of their

surprisingly interesting and readable French Revolutionary era textbooks

work that reflects his ever-facile writing ability, superb wit, and

unconventionality.

His major books include Napoleon's Satellite Kingdoms

(1965; revised paperback edition, 1969; and 1990); The Gentle Bonaparte:

A Biography of Joseph, Napoleon's Elder Brother (1968); The Epoch of

Napoleon (1972, 1978); French Revolution and Napoleonic Era (1979, 2nd

edition 1991); Blundering to Glory (1987, paperback edition 1990, 1998);

and with Fred Hambree, The French Revolution (1993). Dr. Connelly also

produced the major English-language, American, college-library reference

work for the Napoleonic era in the Greenwood Press French history

series: The Historical Dictionary of Napoleonic France (1985), serving

as general editor and author of 157 articles with Harold T. Parker,

Peter Becker and June K. Burton as Associate Editors.

Mike Connelly lives, he says, on "a few parched acres" near Hopkins,

South Carolina, with his wife of over 30 years, Michale Karnes Connelly,

who has an M.A. in History, but works part-time as an echocardiographer.

He credits her with raising their children, thereby allowing him "the

time to make such success as I have." They are understandably proud of

all three: the eldest, Michael Owen, is a 1989 graduate of the U.S.

Naval Academy, a nuclear engineer and author of a novel [written under

the pseudonym Michael S. McDowell], Anonymous Sender (1996); Alexandra

(Lexi) has a B.S. and M.S. in Public Health; and Rachel is a

kindergarten teacher. All are musicians: Mrs. Connelly plays "concert

quality" piano; and Professor Connelly claims the children take after

her whereas "I butcher tunes on the guitar on occasion." Besides their

stable of horses [discussed below and see photos], the family has two

dogs and five cats.

What are your official titles? How long have you held them?

CONNELLY: McKissick Dial Professor of History, University of South

Carolina, since 1991; Professor at U.S.C., 1970-1991; Director of

Graduate Studies (History) for three terms over the years.

In addition to holding the McKissick Chair, have you received any

special awards, titles, medals, or honorary degrees for your work?

CONNELLY: I was elected a Member of the Institute for Advanced Study,

Princeton, New Jersey in 1989; have since belonged to Member's

Association (AMIAS), and returned almost every year. I was Chair of the

European History Section of the Southern Historical Association in

1982-83 and President of the Society for French Historical Studies in

1988. The U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (Ft. Leavenworth,

Kansas) did me honor by offering me the "Morrison Chair" for 1981-82,

but I was unable to accept it because of prior commitments. I lectured

at West Point and the Marine Staff College at Quantico, Virginia, in

1992. At the University of South Carolina, I won the Russell Award for

Research and the Ochs Award for Contributions to the U.S.C. Graduate

History Program (three times).

What were the occupations and educational levels of both of your

parents?

CONNELLY: The Connelly family dates from ca. 1750 in the North Carolina

mountains (Connelly Springs is still on the map). My great-grandfather,

Jesse Conley (as he chose to spell his name) was in the Confederate

cavalry, 1st North Carolina Cavalry Brigade. My mother's family (Earle)

was English, and came to America (Virginia then South Carolina) even

earlier.

My father went to Duke (then Trinity College) for a few years, but

dropped out and volunteered to serve in World War I in France, then went

into his father's business in Morganton, N.C.

What sort of enterprise was that?

CONNELLY: General stores, hardwood [dogwood, oak, maple, cedar, that he

sold to manufacturers in the North, mostly], real estate, and

miscellaneous.

And your mother's education?

CONNELLY: My mother never went beyond high school, normal in her time,

though she could have; her father was a physician (M.D. from Johns

Hopkins), and not poor, although a "country doctor", who was often paid

in chickens or pigs, or not at all. She had been valedictorian of her

high school class, and was better educated, I think, than most college

graduates today. It was she who encouraged me to read, and insisted that

I go to college. (My father didn't object, but viewed college as

optional.) I wanted to go to West Point, and got an alternate

appointment, but the primary appointee did not step aside. Close but no

cigar!

What motivated your original interest in history in general?

CONNELLY: Reading, begun very early. I graduated from high school at 16,

and had already read a lot of literary history, e.g., Emile Ludwig's

Napoleon. As subjects in school, however, I preferred science and

mathematics. I was a physics major (math minor) in college (my first

degree was a B.S. in Physics, cum laude); then I went into the Army

(with every intention of making it a career).

And in French Revolutionary/Napoleonic history per se?

CONNELLY: Looking back, I think I became interested in Napoleon in High

School. Physics took up my time in college, though I read fiction and

some popular history for relaxation. In the Army, I read military

memoirs, history, biography, and fiction. However, when I left the U.S.

Army for graduate school (at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

I knew only that I wanted to study European history.

When I registered, my only real choice of a seminar (required) was in

French Revolution/Napoleon, under Professor George Taylor (later famous

for helping explode the Marxist interpretation of the Revolution). By

the end of the semester, I was up and away on a dissertation in

Napoleonic history under Taylor (never published and best forgotten).

George later became a good friend. In 1979, when I published a textbook,

French Revolution/Napoleonic Era, he adopted it for his undergraduate

class at U.N.C., which I considered an honor.

Would you say that you planned your career or did it result from a

series of accidents?

CONNELLY: Everyone's career is affected by "accidents", but you choose

the road on which they will occur, as it were. Napoleon said that

everyone has the same luck [". . . tous les hommes ont le m๊me dose de

bonheur."]; what one did with it was what counted; even "bad luck"

offered opportunities. I think he was right.

I was fortunate, after a year in a temporary position, to get a

tenure-track job in my specialty, and worked hard at it, teaching and

submitting articles for publication.

The first article to see print was read by Herbert Rowen (Rutgers), who

was an academic editor for Free Press-Macmillan. He wrote me from

Amsterdam (where he was doing research in Dutch history), asking if I

would write a book on "Napoleonic Imperialism."

After 30 seconds or so of thought, I replied YES but that I believed I

could do a better job if I limited it to the kingdoms Napoleon founded

perhaps under the title Napoleon's Satellite Kingdoms. Herb (who became

a lifelong friend) bought the idea and the title. Three years later

(1965), NSK was published: in 1966, Robert Holtman of Louisiana State

University (whom I didn't know at the time) a "name" in Napoleonic

scholarship was kind enough to review it favorably in the American

Historical Review, and my writing career was launched. I have not been

without a book contract since.

In 1971, Bob Holtman and I were among the founders of the Consortium on

Revolutionary Europe, so I have seen him yearly since, and he has

remained a good friend. Also through the Consortium, I got to meet

people like Peter Paret, David Chandler, Louis Bergeron, Jean Tulard,

Ulane Bonnel, R.R. Palmer, Elizabeth Genovese, the late Felix Markham,

and others. Peter Paret became an especially good friend, to whose

advice I owe a great deal. But enough.

How did you land your first job as a historian and how long did it take?

How old were you then?

CONNELLY: I became a full-time instructor at Chapel Hill [the University

of North Carolina's main campus] while in Grad School. In 1960, when I

got my Ph.D., Harold Parker at Duke University was taking a sabbatical

in France. I interviewed for and got a job "taking up slack" at Duke

(1960-61). Since I'd spent six years in the Army and four in Grad

School, I was bald, 31, and looked older, but that turned out to be an

advantage in getting a job and teaching.

At Duke, I had the singular privilege of getting to know Harold Parker,

who gave me advice, and even sent me archival documents on microfilm

from Paris. Later, he wrote the introduction to Napoleon's Satellite

Kingdoms. Others at Duke especially Joel Colton and Ted [Theodore]

Ropp became my friends.

CONNELLY: Yes. Korean War. Did what amounted to 2 tours (1950-52).

Infantry officer. Was shot at a few times.

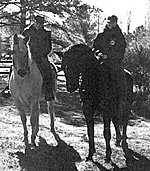

At right, (from left to right), Capt. Connelly, Lt. Col. Dexter, XO Major Smith, 1955.

Did you receive medals?

CONNELLY: Yes, was decorated, but nothing to shout about. I was never a

hero. Heroes were such as Ralph Puckett and the men of the Eighth Army

Ranger Company (which was disbanded after seven months of bloody actions

and high casualties in March 1951). My major problem was "escaping" from

a succession of headquarters but I did, at intervals, and was briefly

CO, 8047 AU.

Did military service affect your historical career significantly?

CONNELLY: Yes. For years, it kept me out of military history. I had (and

still have) an intense loyalty to the U.S. Army and especially the

Rangers. However, although I had been a "regular", I didn't think that

qualified me to write military history. Also, since most of my schooling

had been in science, I didn't feel that I knew enough general history to

put the military part in context. So I chose to deal in general

Napoleonic history.

Although I wrote about Napoleon and his brothers-kings, I did not

publish any military history, per se, until 1987 Blundering to Glory.

It has done well, and maybe, just maybe, the central thesis that

Napoleon was an improviser and scrambler derives from experience. You

find that no plan ever can be carried out exactly; thus a commander at

any level who cannot improvise is "dead".

Please describe your major research. What made you choose this subject?

CONNELLY: Napoleonic Empire, beginning with Napoleonic Spain under

Joseph Bonaparte. The French Revolution. European Historiography is

something I only teach, but it has reinforced my primary research.

Lately I have ventured into general military history (and hope not to be

KIA by the longtime pros in the field). My last article was "US Army

Rangers" for the Oxford Companion to American Military History.

What made me choose history and stay with it? I like what I do. Anyone

who does anything for another reason, including "big bucks," will fail.

CONNELLY: No research assistants per se. I've never let anyone do my

research or writing. I've always given my assistants (when I had any)

tasks to save me time such as finding specific items in the library

and bringing them to me or latterly, scanning (putting on a computer

disk) specified parts of books or documents.

There's one variation on the above. While working on the Dictionary of

Napoleonic France (1985), I had an assistant, Janice Seaman Berbin, who

could take shorthand (and was a stickler for accuracy). I dictated many

articles to her. Her name is on the title page, deservedly.

I also had Co-editors on the Dictionary, as my interviewer knows: June

Burton, Harold Parker, and Peter Becker. Without them (and Janice

Berbin) I would never have finished the monster.

Co-authors? One. I did a French Revolution in 1993 with Fred Hembree,

whose very exceptional Ph.D. work I supervised.

How many graduate students have you produced and what topics did they

work on?

CONNELLY: Perhaps ten Ph.D.'s and twenty or so M.A.'s. Subjects: various

topics in the 18th Century, French Revolution or Napoleonic Era,

including military mostly in French history, but not exclusively. One

Ph.D., John Stine, wrote on the Prussian Army, 1786-1806, trying to

explain why Napoleon destroyed it so easily. (His answer was that the

Army had remained unchanged since the heyday of Frederick the Great.)

Jack Meyer, whom some readers may know personally or from his Napoleonic

bibliography wrote a dissertation on the Battle of Vitoria (Spain,

1813).

Do you yourself have plans for future research?

CONNELLY: I have contracts for three books at present two in general

military history and one on French Revolutionary and Napoleonic warfare.

In addition, Harcourt-Brace is planning a 3rd Edition of my textbook,

French Revolution/Napoleonic Era, and Scholarly Resources a new edition

of Blundering to Glory. So I'll keep busy.

How would you compare the state of the historical profession in the US

today to when you began your career?

CONNELLY: There were fewer activists and more historians seeking the

truth when I entered the profession, and more freedom of expression. It

was de rigeur to let everyone speak on a given question, and if you

disagreed with what anyone said to paraphrase Jefferson (or maybe

Voltaire) to "defend to the death his right to say it."

The tendency now is to prevent the expression of unpopular views, or howl them down,

which I consider Fascist behavior. In the 1960s there were some

historians with political agendas, but there are many more now. Their

activism inclines them to warp the truth to serve a current purpose.

Historians now are less genteel than football coaches, who normally

don't carry their enmities beyond the playing field. Professionals once

could differ violently on issues historical or otherwise and still

be friends. No more. This loss of civility is more than unfortunate, it

has plunged the profession into a kind of barbarism. "Politically

correct or Perish" is the motto. Unhappily, the traditional sorts of

history political, diplomatic, military are under attack as

irrelevant, whereas they are a necessary backbone for all the other

varieties of history social, cultural, and economic included.

Who do you think are today's leading Napoleonic scholars/writers in the

US and abroad?

CONNELLY: I'll stick to Napoleonic history, perhaps lapsing into French

Revolution in military history. In the United States, Peter Paret,

Harold Parker, John Elting, Gunther Rothenberg, Robert Holtman, Steven

Ross, Jeanne Ojala, Susan Conner, Sam Scott, and Isser Woloch. John

Tone, Alexander Grab, and Milton Findley should shine in the future. In

Great Britain: David Chandler, Christopher Duffy, Geoffrey Ellis,

Marianne Elliot, and Alan Forrest; John Esdaile seems to be moving up.

In France, the top living scholars are Jean Tulard, Jean-Paul Bertaud,

and Louis Bergeron.

Looking back over your education, preparation and career, would you

change anything if you could relive it?

CONNELLY: I have thought from time to time that I should have stayed in

the military because the Army treated me exceptionally well. But I guess

I made the right decision. Also, I believe I could have gone to Graduate

School at Yale. (The Army sent me to Yale for a year: I did OK; got my

commission there.) But although that might have given me an initial edge

in the academic job market, I don't think I would have been any better

trained than I was at U.N.C..

Have any particular historical societies contributed to the Renaissance

in French Revolutionary/Napoleonic studies or military history?

CONNELLY: In the United States and Canada, the Napoleonic organizations,

and the International Napoleonic Society, have done a lot to mobilize

non-academics. Basically, however, the impetus has come via open

meetings and books by members from academic organizations the

Condents. Of course, I also shovel a lot.

I think my knowledge of horses the personalities, strengths and

weaknesses of various breeds has helped me understand why Napoleon

loved his gentle but spirited gray Arabian, why many heavy cavalry

horses were bought in Germany Trakehners from the Prussian Royal Stud,

and other tall, big-boned and heavy, but steady breeds and other such

things. I think also I can better understand the problems of a

"horseborne" army, where the movement of every piece of artillery and

the trains depended on having well-fed, healthy horses, and men who

could handle them. (Even today, with trucks and trailers, it's a

gigantic undertaking to get to a horse show with horses and riders

intact with their saddles, bridles, saddlepads, martingales, crops,

etc., not to speak of clothing and hay in haybags [and maybe grain]

for the horses, waterbuckets and lunging ropes, halters, brushes,

hoof-picks, liniment, and horse-blankets or sheets. And I could go on .

. . .)

Although I never served in the cavalry (long gone when I entered the

Army), I feel that I can appreciate the difficulties of fielding cavalry

(training horses and riders; instilling discipline in riders for the

long march; controlling both under fire; making provision to prevent or

control damage from horses-run-amuck, etc.). Most everyone is aware of

the ้lan of Napoleonic cavalrymen, but not the everyday dangers they

faced. Your best old friend, if startled, may kick your head off.

Perhaps it's easier for a horseman to imagine what being in a cavalry

charge was like In the midst of hundreds of "freaked-out" horses,

weighing 1,000 to 1,600 pounds each) and the hazards, even before

closing with the enemy.

While you have horses for a serious hobby, some people think of

Napoleonic/military/history as theirs. Can you suggest ways for "buffs"

to contribute?

CONNELLY: Join one or more of the Napoleonic societies. Go to meetings.

Offer papers, if you have the inclination. Participate in war games and

re-enactments. But read and hold the organizers of these things to

achieving as much authenticity as possible.

From your extensive traveling, can you suggest the most interesting

museums to familiarize laymen with the French Revolutionary era?

CONNELLY: Well, there's no place like France, notably Paris and

vicinity: Les Invalides, location of Napoleon's tomb (but, ironically,

built by Louis XIV); l'Ecole Militaire, where Napoleon went to school;

the Archives de Guerre at Vincennes, with its museum; the Panth้on;

Versailles (Bourbon, but with many Napoleonic paintings); Malmaison,

Josephine's chโteau, which has the most Napoleoniana. Paris itself is a

monument to Napoleon, who built the Arc de Triumph, Arc du Carrousel,

and whose statue is atop the Vend๔me Column. (Of course, the basic

"wheel-spoke" design of the city, with the Arc de Triomphe as the hub,

was imposed by Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann.)

There are reminders of Napoleon all over Europe, and not just at the

battlefields. There is the Gauss "observatory" at G๖ttingen; the city

gates at Milan; the coliseum and Trajan's column at Rome, uncovered by

Napoleon's engineers; and much else.

Despite the fact that so much has already been written on the subject,

what opportunities for research and popularization exist today?

CONNELLY: Most scholars in the field have worked (and still do) in the

French Revolution. So much has been done that historians are reduced to

analyzing fruit festivals and speculating on the social impact and

philosophical meaning of bare-breasted styles. On the other hand, the

history of France in the Napoleonic period is still to be written in

every conceivable aspect. The same is true for the Napoleonic Empire;

there is a crying need for military, political, diplomatic, economic,

social, cultural, religious history of every state and annexed

department and ultimately a definitive synthesis.

Alex Grab's work on Napoleonic conscription in Italy shows that new

things are possible in military history. In fact military history needs

a total reworking campaign by campaign and battle by battle as well

as in the administration, logistics, staffing, procurement and

manufacture (especially of weapons) and organization of the armies.

(Colonel John Elting may be classed among the new historians for his

work on the Grande Arm้e.) We distinctly lack careful views of the

"other side" in the French Revolutionary/Napoleonic wars. Accounts now

extant are still mostly French or British.

As for sources: the Archives of France, Germany, Italy, Austria, Spain,

the Netherlands, Denmark, Scandinavia and the Balkans are full of unused

primary sources.

Do you have any advice for young scholars just entering the field?

CONNELLY: Ask yourself if you love the work you're doing. If you can

answer Yes, work hard and pray a lot.

To be really successful to excel as a historian, soldier, doctor,

lawyer, captain of industry, or Indian chief you must love what you

are doing, and (without a thought) put your work ahead of everything

else. The history profession surely for publishing scholars is like

the Christian ministry or priesthood. Incomes are pitiful. "Laymen"

never understand what you're doing, and think you're nuts, or worse. If

you don't love the history profession, you don't belong in it.

That is not to say that a person cannot pursue a career or trade

(academic or other) for the comfort of money, and be recognized as a

successful citizen. But, to paraphrase the late David Pinkney (drawing

on Eugen Weber): "Great history is not written by good [citizens] but

odd-balls and monomaniacs." And it is writers of history who supply the

material for college teachers' lectures.

Did you serve in the armed forces during wartime?

Did you serve in the armed forces during wartime?

When I returned stateside, I was an instructor, later

Executive Officer, in the Florida Ranger Camp (Amphibious and Jungle

Warfare), and served in the Special Weapons Command. At right, camp July 1956. Connelly is back row, third from right.

When I returned stateside, I was an instructor, later

Executive Officer, in the Florida Ranger Camp (Amphibious and Jungle

Warfare), and served in the Special Weapons Command. At right, camp July 1956. Connelly is back row, third from right.

Military schools like to attach a system to every commander. That makes

teaching easier, but is unrealistic; if a general had a system, the

dumbest enemy would figure it out and devise a way to beat it. I believe

that all great combat leaders have been improvisers (and, as to taking

risks, a little crazy). I'm now writing a book that I hope will prove

it. Napoleon, I think, had "soulmates" in Frederick the Great, Stonewall

Jackson, and George Patton, to name a few.

Military schools like to attach a system to every commander. That makes

teaching easier, but is unrealistic; if a general had a system, the

dumbest enemy would figure it out and devise a way to beat it. I believe

that all great combat leaders have been improvisers (and, as to taking

risks, a little crazy). I'm now writing a book that I hope will prove

it. Napoleon, I think, had "soulmates" in Frederick the Great, Stonewall

Jackson, and George Patton, to name a few.

Do you have any research assistants? Co-authors? Or have you always

worked alone?

Do you have any research assistants? Co-authors? Or have you always

worked alone?

My experience has also allowed me to damn cavalry leaders at certain

times, e.g., Murat on the march into Russia, where he ran his horses to

death hundreds of them. He also murdered the infantry following them.

Napoleon ordered him to advance sur-le-champ et เ bride abattue [at once

and to ride hell for leather], but a cavalry leader should know the

limits of horses. They must be moved over long distances mostly at a

walk, and watered and fed regularly; otherwise they will not have the

strength to charge when called upon. Under stress, horses do not have

the long-term endurance of men.

My experience has also allowed me to damn cavalry leaders at certain

times, e.g., Murat on the march into Russia, where he ran his horses to

death hundreds of them. He also murdered the infantry following them.

Napoleon ordered him to advance sur-le-champ et เ bride abattue [at once

and to ride hell for leather], but a cavalry leader should know the

limits of horses. They must be moved over long distances mostly at a

walk, and watered and fed regularly; otherwise they will not have the

strength to charge when called upon. Under stress, horses do not have

the long-term endurance of men.

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #12

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com