The following has been adapted from Ed Wimble's considerable research in preparing his excellent series of board games on the 1815 campaign. We have relied heavily onhis narrative beginning with the morning of 17 June. In the turmoil of historical controversey regarding Marshal Grouchy's actions, Wimble takes a moderate view. However, in order for our readers to fully consider for themselves the implications of Grouchy's decisions, we offer several other opinions.

The Prussian retreat from the battlefield of Ligny would come to be one

of the most famous in all history, but in

the dark, chaotic hours immediately after the battle, in which the two premier

fighting corps of the Prussian Army had

been shattered, confusion reigned.

Blucher was missing and feared to be

captured, communications with

Wellington were completely severed,

and the entire campaign appeared on

the verge of being irrevocably lost.

The Prussian retreat from the battlefield of Ligny would come to be one

of the most famous in all history, but in

the dark, chaotic hours immediately after the battle, in which the two premier

fighting corps of the Prussian Army had

been shattered, confusion reigned.

Blucher was missing and feared to be

captured, communications with

Wellington were completely severed,

and the entire campaign appeared on

the verge of being irrevocably lost.

Looking over their shoulders at the billowing smoke and raging fires which lit up the villages they had fought so hard to hold, the Prussian army must surely have believed they were at the beginning of a long and bitter retreat. To make matters worse, in addition to an estimated 15,000 battle casualties, perhaps as many as 10,000 demoralized or disaffected troops would avail themselves of this opportunity to abandon the Army of the Lower Rhine.

The only thing the Prussians could be thankful for was that they had held on at Ligny until nightfall, and that the French, due to a combination of fatigue, rain and darkness, were unable to pursue. Here some credit must be given to Thielemann's rear-guard, as his relatively undamaged III Corps did not succumb to panic and made a firm showing at Sombreffe, which discouraged any small French pursuits. The Prussians were also fortunate in that French General d'Erlon, and his large I Corps of four infantry divisions, one cavalry division, and nearly 50 artillery pieces, had spent the afternoon and evening marching back and forth between the two battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras; his corps' timely arrival at either action would have won Napoleon a decisive outcome.

D'Erlon's blunder becomes

magnified when one realizes that

his column's approach to Ligny

upon the exposed right flank of

the Prussian army late that afternoon-and then its rather mysterious halt and turn around caused a great deal of panic in the

rear of Vandamme's corps on the

extreme left of Napoleon's battle

line. This confusion delayed the

French Imperial Guard's decisive

attack for two or three critical

hours. Rather than falling upon

the collapsing rear of a defeated

Prussian army, not one of

d'Erlon's men took part in the

battle or the subsequent pursuit.

D'Erlon's blunder becomes

magnified when one realizes that

his column's approach to Ligny

upon the exposed right flank of

the Prussian army late that afternoon-and then its rather mysterious halt and turn around caused a great deal of panic in the

rear of Vandamme's corps on the

extreme left of Napoleon's battle

line. This confusion delayed the

French Imperial Guard's decisive

attack for two or three critical

hours. Rather than falling upon

the collapsing rear of a defeated

Prussian army, not one of

d'Erlon's men took part in the

battle or the subsequent pursuit.

So, largely through command

friction and incredible mistakes

by the French, an almost miraculous respite had been granted,

during which the Prussian commanders frantically gathered

their scattered troops, assigned

retreat routes, and designated

points on the map where they could

rally the army. In a twist of fate, Wavre,

thirteen miles north, was chosen as the

assembly point rather than acting army

commander Gneisenau's first choice,

Tilly (less than three miles from the

battlefield), because it was the only town

consistently shown on all of the Prussian commander's maps.

The only thing the Prussians

could be thankful for

was that they had held on

at Ligny until nightfall...

Thus, as each hour passed, the grim and dire crisis faced by the Prussian army diminished. The irrepressible Blucher, who, knocked unconscious and trapped beneath his fallen horse after leading several last-ditch counter-assaults, had been ridden over by French cuirassiers. Within their very grasp, not one Frenchman spotted Blucher in his predicament, and under the cover of a rather providential rain storm, Lt. Colonel von Nostitz and members of the Prussian 6th Uhlans managed to extricate the impetuous old cavalryman. One can only imagine the relief felt at Prussian headquarters when Blucher was returned hours later-bruised, wet, and only half-sentient-but very much alive. By morning, he would be back in the saddle, possibly still muddled. However, his appearance, as a much beloved figure to the rank and file who had come to embody the redemption of the Prussian army from the disgrace of Jena, had an incalculable effect in restoring heart to his men. Furthermore, despite Gneisenau's reluctance stemming from his dislike and mistrust of the English, Blucher had resolved to march to Wellington's aid, and to risk battle again as soon as possible.

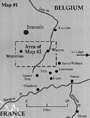

But perhaps as important as Blucher's return was the fact that the Prussian army was managing to slip away, separating from the French army so much so that by dawn contact had been virtually broken. The heavily damaged I and II Prussian Corps-the two "battle corps" of the Army of the Lower Rhine which contained the most experienced and elite formations of the army-had retreated through Tilly and were heading north to Wavre. Of the inferior two "corps of position," Thielemann's III Corps had retreated toward Gembloux where it was to link up with Bulow's unbloodied IV Corps, which was only just arriving on the scene.

The Prussians had three possible retreat routes:

1) due north to Wavre;

2) east to Namur along their main line of supply and communications; or,

3) to the northeast via Gembloux directly between these two other routes.

Contact having been broken, the

French could only surmise where the

Prussians were headed and for what

purpose. Napoleon believed that the

Prussian army, dealt a severe and disabling blow, would most likely retreat

eastward toward Liege (their base of I

supply) via Namur, though he did not

discount the Prussian's other options,

namely, to attempt to join with

Wellington's army or to retire to Brussels and offer battle again there.

Napoleon's Pursuit After Ligny: The View from West Point

Therefore, on the morning following the battle at Ligny and Quatre Bras, the Emperor decided to turn his attention to destroying Wellington with the main body of his army. He chose to detach Marshal Grouchy, with a sufficiently large force, to maintain the apparently widening gap between the two Allied armies. Grouchy, during the 1814 campaign, had been given a similar pursuit mission against Blucher's army in France, and he came awfully close to bagging Blucher and his entire command. As it was, Grouchy had conducted a text book pursuit and took many prisoners. He displayed great initiative in finding a parallel pursuit route which enabled him to get behind many of Blucher's troops after the battle of Vauchamps.

Thus, in 1815, Napoleon's choice to bestow Grouchy with the coveted Marshal's baton seemed only just. He had been one of the few French general's to shine in the twilight of Napoleon's last campaigns, and he seemed to possess the proverbial "fire in the belly" that Napoleon looked for in his Marshals. It would seem that Grouchy was exactly the man to conduct the operation Napoleon now had in mind: the pursuit of a defeated Prussian enemy.

Grouchy Receives His Orders

Napoleon's initial orders to Grouchy indicate his uncertainty concerning the Prussian's ultimate intentions:

"...It is important to penetrate what the enemy intend doing, whether he [Blucher] is separating himself from the English, or whether they meditate uniting to cover Brussels or Liege by risking the fate of another battle. In all cases, keep constantly your two infantry corps within a league of ground, and occupy every evening a good military position, having several avenues of retreat. Post intermediate detachments of cavalry, so as to communicate with headquarters...." Closing Statement of Napoleon's Orders to Grouchy, transcribed by Grand-Marshal Bertrand, Ligny, 17 June, 1815.

Grouchy later denied repeatedly that he received this written order prior to 18 June. However, he eventually conceded that he was aware immediately of his orders which were apparently received by 11:30 a.m on the 17th. In a dispatch dated the same day (17th) at 10:00 p.m., Grouchy confirms that he understands that one of the Prussian options was a retreat to Wavre and that he was to follow them in that direction in order that they may not reach Brussels, and to separate them from Wellington.

Grouchy's Pursuit Starts Late

Armed with his orders placing him in command of approximately 33,000 men, Grouchy joined General Vandammes's late-starting III Corps as it neared Le Point du Jour, and from there moved on to nearby Gembloux in a terrific thunderstorm (this heavy precipitation, which appears to have begun around 2:00 p.m., was the same fateful storm that Napoleon was encountering on the road to Genappe).

Grouchy had been understandably deliberate in getting his columns into action the 17th. His new command had done the brunt of the fighting the day before at Ligny, not to mention the grueling marches prior to the commencement of the campaign. Vandamme's and Gerard's two corps needed food and rest. However, Grouchy compounded the delay by ordering Vandamme's III Corps to move out ahead of Gerard's IV Corps. Napoleon, with the main forces of his Army of the North, moved out toward Quatre Bras late on the morning of 17 June. In order to prevent his command from crossing columns with the Emperor's, Vandamme was forced to detour his line of march to a point where it actually had to pass the corps of Gerard as it stood idly by watching. This alone delayed Grouchy's infantry pursuit three hours.

In addition to the two infantry corps, Grouchy had been given command of Pajol's I and Exelmans' II Reserve Cavalry Corps, which were not as tardy as the infantry in their pursuit of the Prussian army. Pajol started at 4:00 a.m. on 17 June, probing east toward Namur while Exelmans moved northeast to Gembloux. Apparently none of Grouchy's cavalry moved directly north along the path of the Prussian I and II Corps' retreat. Milhaud's cavalry had started along this route, but it was pulled back to rejoin the main column's march against Wellington.

At approximately 9:30 a.m. on the 17th,

Exelmans encountered the whole of

Thielemann's III Prussian Corps in the

vicinity of Gembloux, only eight miles from

the center of the Ligny battlefield. Not

only did Exelmans fail to press the

Prussians, but also, even more

astonishingly, he did not inform Grouchy

or Pajol of his vital discovery.

Pajol, would provide

equally faulty information,

... due to an excess of zeal.

This seems

an incredible lapse in the manner one

would expect a veteran cavalry commander

to conduct a mission of pursuit and

reconnaissance. This lapse by Exelmans

deprived Grouchy of the critical knowledge

that the Marshal could have exploited

quickly and decisively as per his orders.

The enormity of Exelmans' failures on this

day can't be really overstated, and he

bears a large part of the culpability usually

placed upon Grouchy for failing to

comprehend a dangerously developing

situation.

Exelmans: The Real Villain of 1815?

Ironically, at the same time, Grouchy's other key cavalry subordinate, Pajol, would provide equally faulty information, this time due to an excess of zeal. Pajol's troopers, considered one of the finest bodies of French light cavalry, reached Le Mazy on the road to Namur after having captured a complete Prussian battery that had lost its way the previous night. Unfortunately for the French, Pajol's success and reports of Prussian refugees streaming eastward to Namur reinforced Grouchy's and Napoleon's erroneous impressions that the Prussians were in fact retreating along their line of communications toward Liege and away from Wellington's army (Pajol reported this directly to both Grouchy and the Emperor).

Teste's infantry division (detached from the VI Corps) was ordered to move off toward what was essentially a false trail composed of stragglers, deserters and ineffectives. Because of the false impression they conveyed, these demoralized troops may have performed a far more valuable service to Blucher than if they had remained with their units!

Grouchy's conduct in the first phase of the pursuit is forgivable based on Exelmans' failure and the false impression created by Pajol's success, but he must accept responsibility for the incredible lack of reconnaissance toward Wavre, which still remains unexplained.

Exelmans' failure also enabled Thielemann to reach all the way to Wavre with the lead elements of his strung-out corps by 8:00 p.m. the evening of the 17th, almost fifteen miles in six hours, despite the rain-soaked roads (Borcke's brigade, for example, spent the night in Corbaix). The Prussian recovery after its beating at Ligny had coalesced.

The terrible rainstorm appears to have also dampened Marshal Grouchy's spirit, and he called for a halt at this point prematurely, after pushing Exelmans only a few miles farther to Sart a Walhain. The 15th Dragoon Regiment was sent to reconnoiter towards Perwez, and scouts were sent to Tourinnes and Nil St. Vincent.

Pajol, in the meantime, had finally determined that the Prussians retreating to Namur were not Blucher's main force, and he returned to Le Mazy with Teste's infantry and Soult's (the Marshal's brother) cavalry. All in all, the infantry under Grouchy's command had scarcely pursued the Prussians for more than five miles on the 17th, the cavalry just twice as much.

As a consequence of the pursuit's overall ineffectiveness so far, Grouchy still had no idea where the Prussians really were. He had only managed to form some doubts that they had really fallen back toward Liege via Namur as Napoleon had hoped. At 10 p.m. on the 17th, he sent the following dispatch to the Emperor from Gembloux:

"Sire, I have the honour to report to you that I occupy Gembloux and that my cavalry is at Sauveniere. The enemy, about 30,000 strong, continues his retreat. We have captured here a convoy of 400 cattle, magazines and baggage.

"It would appear, according to all reports, that, on reaching Sauveniere, the Prussians divided into two columns, one of which must have taken the road to Wavre, passing Sart a Walhain; the other would appear to have directed on l'Perwez.

"It may perhaps be inferred from this that one portion is going to join Wellington; and that the center, which is Blucher's army, is retreating on Liege. Another column with artillery has retreated by Namur. General Exelmans has orders to push, this evening, six squadrons to Sart a Walhain, and three to Perwez. According to their report, if the mass of the Prussians is retiring on Wavre, I shall follow them in that direction, so as to prevent them from reaching Brussels, and to separate them from Wellington. [emphasis added - Ed.] If, on the contrary, my information proves that the principal Prussian force has marched on Perwez, I shall pursue the enemy by that town.

"General Thielemann and Borstel

[Borcke?] formed part of the army which

Your Majesty defeated yesterday; they were

still here at 10 o'clock this morning and

announced that they have 20,000 casualties.

"the movement of retreat

of Blucher's army appears

to me very clearly

Brussels."

They inquired, on leaving, the distances to Wavre, Perwez, and Hannut. Blucher has been slightly wounded in the arm, but it has not prevented him from continuing to command after having his wound dressed. He has not passed by Gembloux.

"I am, with respect, Sire, Your Majesty's faithful subject,

"Marshal Count Grouchy"

Grouchy's evening orders instructed Vandamme to march on Sart a Walhain at 6:00 a.m. the following day (daylight would be at 4:00 a.m. on the 18th), while Gerard was to follow the same path at 8:00 a.m. Pajol was ordered from Le Mazy to Grand Lez taking with him Teste's division.

A retired French veteran, now living in Belgium, was brought into camp late that night (the 17th). He emphatically stated that the Prussians had partially moved on Brussels by way of Wavre, but that a very large body of their troops had occupied the plateau of the Chysse; it being their intention to move on Brussels also but more from the direction of Louvaine. Around 2:00 a.m on 18 June, Grouchy sent Napoleon a copy of his orders to his subordinates along with the latest intelligence that "the movement of retreat of Blucher's army appears to me very clearly Brussels."

Grouchy's impression was that the

Prussians were retreating north to Brussels,

but the possibility of Blucher turning west

from Wavre to join Wellington well south of

Brussels seemed ignored. It was still possible

for Grouchy to slow the Prussian movement

or draw off some of their troops attempting to

move against Napoleon. However, it would

require that he move relatively quickly to the

northwest, angling between the Prussians and

Napoleon. To accomplish this, he would have

to cross the Dyle River at either Moustier,

Ottignies, or Limalette.

Grouchy's impression was that the

Prussians were retreating north to Brussels,

but the possibility of Blucher turning west

from Wavre to join Wellington well south of

Brussels seemed ignored. It was still possible

for Grouchy to slow the Prussian movement

or draw off some of their troops attempting to

move against Napoleon. However, it would

require that he move relatively quickly to the

northwest, angling between the Prussians and

Napoleon. To accomplish this, he would have

to cross the Dyle River at either Moustier,

Ottignies, or Limalette.

Grouchy's Procrastination on 18 June

By continuing with his leisurely pursuit, Grouchy bungled his second opportunity to fulfill Napoleon's expectations. He did nothing to insure that his men moved out at their appointed hour (6:00 a.m.), nor was the direction of march altered to one more directly upon Wavre or the nearer crossings over the Dyle (Sart a Walhain is decidedly east of Gembloux, chosen because it lay midway between the Wavre and Perwez roads).

In addition, although in bivouac for twelve hours, a tussle broke out between the men of III and IV Corps over the distribution of breakfast (the captured column mentioned in Grouchy's letter). As a result, Vandamme did not move his men out until 8:00 a.m., two hours later than his orders specified. If Grouchy were under any impression that speed was of the essence, one cannot find evidence in the way in which he supervised his wing on the morning of 18 June!

Grouchy reached Walhain between ten and eleven that morning and prepared a dispatch for the Emperor while having breakfast. In this he states that three of Blucher's corps were marching towards Brussels while another group appears to have moved toward the Chysse River.

Because the Chysse is to the east of Lauzelle, if the Marshal were to proceed directly on Wavre from the south, entering the defile from this direction might have appeared to him akin to sticking his head into a noose.

The lack of reconnaissance to the north, and the premature halt of the pursuit on the 17th was compounded by Grouchy's slow start and excessive caution on the morning of the 18th. Grouchy also stated in his dispatch:

"This evening I expect to find my self concentrated at Wavre, and thus find myself between Wellington, whom I assume to be in retreat before Your Majesty, and the Prussians."

With almost uncanny timing, at the same moment the rider sped off, the initial cannonade could be heard coming from Waterloo.

Gerard had ridden in advance of his corps and was just approaching Grouchy's temporary headquarters. That general, in the Marshal's words, "haughtily, and in a fashion in little harmony with the respect due to his chief and military discipline," advocated the right wing should immediately march to the sound of the guns (Gerard did in fact have the reputation of being a bit brusque, tact evidently not being his strong suit). Grouchy, obviously miffed and ever prideful, peremptorily refused Gerard's request.

This altercation took place at approximately 11:30 a.m. To partly understand Grouchy's response to Gerard, we must consider the volume of noise he may have heard at this point in time.

Napoleon began the battle of Waterloo with the assault of Jerome's division (II Corps) upon the Chateau of Hougoumont. Because everyone's watch kept different time in those days, it's impossible to ascertain exactly when this happened, but about 11:20 a.m. seems to be the consensus.

The 12-pounder reserve battery of the French II Corps had been withdrawn to add weight to the grand-battery, at this time just collecting on the Brussels highway; still an hour and a half from getting into its final position. We also know that Bachelu's division along with his guns had been pulled from the II Corps and added to the reserve in the center. This leaves only the batteries of Jerome's and Foy's divisions, and the horse guns of Pire's cavalry division; a total of twenty-two guns.

The history of the battle tells us that Pire's guns were not employed until Wellington had committed Bolton's battery to enfilade Jerome's push to the west side of the chateau, so that Grouchy could not have heard these at 11:30. Thus, it would appear that Grouchy's and Gerard's initial argument could not have taken place to the accompaniment of more than twenty guns. This is not the sound of a great battle, but, as Grouchy at first insisted, more likely that of a rear-guard action.

Of course, we may forgive Grouchy for not marching instantly to the sound of a potentially minor action, especially if it meant abandoning his primary objective, the Prussian army. However, by approximately 1:00 p.m., the French grand battery was in action, and still Grouchy did not reconsider his initial decision to continue north. Grouchy's defenders argue that by then it was too late, that Grouchy's opportunity had passed by earlier, and that his only course at that point was to pitch into the Prussians at Wavre.

Grouchy's detractors, on the other hand, have pointed to Gerard's and Vandamme's reaction (at 11:30 a.m.) as evidence that the opening cannonade at Waterloo indeed may have sounded like the beginning of a major battle. The continuing escalation of sound that occurred over the next two hours, beginning with Jerome's assault at Hougoumont and culminating with D'Erlon's grand assault at 1:30 p.m., would eventually remove all doubt as to the nature of this engagement. Again, the critics feel that Grouchy had time in those two hours to assess the situation, mull over the various possibilities, and to change his mind. At the very least, they argue, he should have allowed Gerard to pursue his plan of marching to the sound of the guns.

But by 1:30 it was probably too late for Grouchy to effectively intervene. And, because the acoustics of battle can be deceiving over any sort of distance, we will never be quite sure how loud the sound was that interrupted Grouchy's famous breakfast of strawberries (Grouchy's detractors have been seized by this detail of that sumptuous meal, largely because it is so wonderfully symbolic of the sort of decadence one might wish to attach to Grouchy's aristocratic background).

Thus, overall, Grouchy's direction of his troops on the 17th and 18th may be partially excusable. But it still begs the question of what could he have accomplished if he had just put a little fire in the stride of his men either day, and arrived in front of Wavre two or three hours earlier? Or, what if he had taken advantage of the mid-June dawn at 3:30 a.m.? Suppose he had marched at 4:00 a.m., he could have been in front of Wavre by 10:00 a.m., just when the latter half of Bulow's IV Corps (the lead Prussian force moving to Waterloo) was just putting out a fire that threatened the ammunition trains. If Grouchy had managed to retrieve merely three or four hours, he might have succeeded in preventing at least some of the Prussians from marching to Waterloo.

As it was, the French pursuit was so lame and ineffective that the Prussians underestimated the size of Grouchy's force by half. This had enormous consequences, as the Prussians felt they had little to fear from the pursuit at their backs, and they felt quite at liberty to march aggressively toward Wellington. (So little was Grouchy feared in fact, that Thielemann was expected to send two of his brigades to Waterloo!)

The Battle of Wavre is Joined

Exelmans' dragoons were the first

to encounter the Prussians. Around

2:00 p.m., Colonel Lebedeur's rearguard detachment from the Prussian IV

Corps found itself surrounded in La

Baraque. Upon the approach of

Vandamme's infantry they fought their

way out by "attacking" to their rear.

Lebedeur successfully found his way

back to the Prussian main body by going around the woods of Lauzelle and

approaching Wavre from Dion le Mont.

Exelmans' dragoons were the first

to encounter the Prussians. Around

2:00 p.m., Colonel Lebedeur's rearguard detachment from the Prussian IV

Corps found itself surrounded in La

Baraque. Upon the approach of

Vandamme's infantry they fought their

way out by "attacking" to their rear.

Lebedeur successfully found his way

back to the Prussian main body by going around the woods of Lauzelle and

approaching Wavre from Dion le Mont.

Exelmans moved off in pursuit

while Vandamme, growing frantic with

his inability to affect events as signalled

by the tremendous barrage to the west

(the French grand battery was now in

full concert), spurred his men onward.

Grouchy rode up and ordered him to

press on to Wavre, take up position on

the heights there, and await further

orders.

"...Maury, seizing the eagle,

cried 'Why scoundrels, you

dishonored me the day

before yesterday, and you

repeat the offense today!

Forward, follow me."

Vandamme, however, was in no mood to wait any longer for his superior-this "general of cavalry"-to make up his mind while the enemy was close at hand. After all, he had waited long enough, having hovered in position at Nil St. Vincent for over two hours (from 10:30 to 1:00) waiting for Grouchy to give him the verbal orders to advance on Wavre. Meanwhile, Grouchy rode over to Limalette to see if he could glean something of the battle around Mont St. Jean, but left no wiser. Just as he rejoined Vandamme a messenger rode up bearing the Emperor's dispatch from Waterloo dated 10:00 a.m. It was now between three and four p.m and the message had taken over five hours to reach Grouchy.

As can be seen from its contents this note contained nothing that would have caused Grouchy to think that he was not, even at that moment, acting in accordance with Napoleon's wishes. Soult to Grouchy, from the battlefield of Mount St. Jean. Sent at 10:00 a.m. and received after 3:00 p.m.

"The Emperor has received your last report, dated from Gembloux.

"You speak to the Emperor of only two columns of Prussians, which have passed at Sauvenieres and Sart a Walhain. Nevertheless, reports say that a third column, which was a pretty strong one, has passed by Gery and Gentinnes, directed on Wavre [This was reported by Milhaud's cavalry before they departed].

"The Emperor instructs me to tell you that at this moment his Majesty is going to attack the English army, which has taken position at Waterloo, near the Forest of Soignes. Thus his Majesty desires that you direct your movements on Wavre, in order to approach us, to put yourself in our sphere of operations, and to keep your communications with us, pushing before you those portions of the Prussian army which have take this direction, and which may have stopped at Wavre, where you ought to arrive as soon as possible.

"You will follow the enemy columns which are on your right side with light troops, in order to observe their movements and pick up their stragglers. Instruct me immediately as to your dispositions and your march, as also as to the news which you have of the enemy; and do not neglect to keep up your communications with us. The Emperor desires to have news form you very often.

"The Marshal, the Duke of Dalmatia, Soult."

Grouchy did, however, order Pajol's cavalry corps to abandon its reconnaissance to the north and east of Tourinnes and to bring its cavalry and Teste's infantry division to Limal instead. There he was to push across the Dyle and attempt to make contact with Napoleon's forces to the west. This was Grouchy's last opportunity to affect the outcome of Waterloo, fleeting though it might be.

Unfortunately again for the French, Grouchy chose to execute the Emperor's order that he should "maneuver so as to bring him close" to the main body in exactly the worst possible way. Pajol's force at this time was the farthest away from Napoleon of the three main groups (Vandamme's and Gerard's corps being the other two) that could have executed this maneuver (Exelmans was with Vandamme).

We can excuse the Marshal for not using Vandamme's III Corps, which was just preparing to storm the Prussian position at Wavre, but Gerard's IV Corps was still on the Brussels highway, its lead elements approaching La Baraque.

The IV Corps probably would not have reached Chapelle St. Lambert until twilight, and thus may not have affected Waterloo's great climax. However, Gerard might have halted Pirch's II Corps, which was the only body of troops in good enough shape after the battle to press and pursue the French. In fact, it was Pirch's lead brigade that eventually wrested Plancenoit from the Guard. Napoleon faults the chaos at the one bridge in Genappe as the final straw that broke the back of the Armee du Nord . Up until that time the retreat had not become a rout, and it seems unlikely that it would have if Plancenoit had remained in French hands.

In any case, by moving Gerard over the bridge at Limal, Grouchy would have split his infantry between the two banks of the Dyle; violating a sound military principal not to divide your forces in the face of the enemy. Thus, it was safer to choose Pajol's cavalry forces to cross over. Satisfied that he had met the letter of the Emperor's orders, the Marshal now took personal control of the assault at Wavre.

Vandamme: Rash and Disagreeable

Vandamme, true to his rash nature and most likely compelled by his anxiety over the fate of the Emperor's main force, had not waited for the Marshal to send him further orders. Instead, without any preparation, he hurled the whole of Habert's division in an assault against Wavre. An eyewitness, Fantin des Odoards, Colonel of the 22nd Line Regiment, gives the following account:

"Instead of crossing the Dyle below Wavre, where it was fordable in many places, General Vandamme ordered us to cross over to dislodge the enemy, walled in the town itself, to capture a bridge carefully barricaded and protected by thousands of marksmen posted in the houses on the other bank. He should have outflanked this strong position, but the general persisted in approaching abreast with masses which, engaged in a long road parallel to the bridge, received all the fire of the Prussians without being able to utilize their own.

"We lost many of our men fruitlessly. The 70th Regiment, the same which had been discomfited two days earlier, now ordered to clear the bridge under a hail of bullets, were driven back in disorder. Rallied by its colonel, it hesitated, when brave Maury, seizing the eagle, cried 'Why scoundrels, you dishonored me the day before yesterday, and you repeat the offense today! Forward, follow me.' Eagle in hand, he dashed over the bridge, the charge beating on the drums, the regiment following him, but scarcely was he to the barricade when this worthy leader fell dead, and the 70th fled more than ever, and so rapidly that without the help of my 22nd, the eagle which was on the ground, in the middle of the bridge, at the side of my poor comrade spread out lifelessly, would have become the prize of the enemy marksmen who were already seeking to seize it...."

Grouchy divided Vandamme's corps

such that a part of Lefol's division

assaulted the Mill of Bierges while another

part pressed the Prussians at BasseWavre.

Exelmans brought his cavalry up on

Vandamme's right but his Dragoons

were relatively useless in this kind of

fighting. Eventually artillery was

established on the heights opposite the

town (one of the cannonballs is lodged

within the church to this day, stuck in one

of the columns and facing the stained

glass window through which it had

passed).

"If a soldier cannot make

his subordinates obey, he

must know how to be

killed!"

Skirmishers of both armies occupied the marshy shrub lined banks of the Dyle, denying each other the opportunity of searching out a fording place. Thielemann expertly kept his reserves hidden in the side streets. Each time the French wrested control of the bridge and its barricades they were met by a howling counterattack of enraged Landwehr set on avenging their defeat at Ligny. The barricade retaken, Thielemann would withdraw his men to await the next onslaught. In all Vandamme launched thirteen assaults on the barricaded Pont du Christ to no avail.

Lefol's battalions met with a similar lack of success in their assaults on the mill, two massive, multi-storied stone buildings on the west bank flanking the small foot bridge. Grouchy replaced these men with those of Hulot's division who had just arrived from the IV Corps. A battalion from the 9th Leger renewed the assault but was repulsed. Gerard came up with another battalion and led it in person across the bridge. He caught a musket ball full in the chest as this attack faltered too.

Gerard was carried away, Grouchy ordered General Baltus from the artillery to lead the next attack. Baltus, judging that it was futile, flatly refused. Scandalized, Marshal Grouchy dismounted from his horse crying "If a soldier cannot make his subordinates obey, he must know how to be killed!" But the attack Grouchy led failed in its turn. Finding the mill as tough a nut to crack as Vandamme was finding the Pont du Christ barricade, Grouchy turned over command back to Hulot and went to find Gerard's other two divisions. It was then that another messenger arrived from the Emperor, dated 1 p.m:

"Marshal:

"You wrote to the Emperor at two o'clock this morning, that you would march on Sart-lez-Walhain; your plan then is to proceed to Corbaix or to Wavre. This movement is comfortable to his Majesty's arrangements which have been communicated to you. Nevertheless, the Emperor directs me to tell you that you ought always to maneuver in our direction. It is for you to see the place where we are, to govern yourself accordingly, and to connect our communications, so as to be always prepared to fall upon any of the enemy's troops which may endeavor to annoy our right, and to destroy them.

"At this moment the battle is in progress on the line of Waterloo. The enemy's centre is at Mont St. Jean; maneuver therefore to join our right.

"The Marshal, Duke of Dalmatia.

"P.S. A letter, which has just been intercepted, says that General Bulow is about to attack our right flank; we believe that we see this corps on the height of St. Lambert. So lose not an instant in drawing near us and joining us, in order to crush Bulow, whom you will take in the very act."

This message took less time to traverse the ground separating the two wings than the one at 10:00 a.m. because the rider chose to move across country rather than follow the main road which had been the prescribed path upon which communications were to travel; i.e., via Genappe, Quatre Bras, Sombreffe, and Gembloux, thus shortening the time this would take by some two hours. Grouchy immediately sent Pajol orders to spur his men onto Limal, then sought out and rerouted Vichery and Pecheaux to second this maneuver (had the 10 a.m. messenger taken the same route, Pajol would have been able to move out two hours earlier).

Pajol, meanwhile, upon reaching Corbaix, found the cavalry of the IV Corps still in place, apparently doing nothing. It was now commanded by Vallin, one of its brigadiers, in the absence of General Maurin who was severely wounded at Ligny. Possibly some confusion resulted from this replacement of leaders which may account for the cavalry's inactivity and unusual deployment at the rear of its corps.

Pajol, having been ordered to cross the Dyle at Limal and to march upon St. Lambert, thus effecting the jointure of both wings as Napoleon had ordered at 1 p.m., would also be able to turn Thielemann's flank by this doubly advantageous maneuver. Pajol immediately placed Vallin's cavalry under his orders, thereby usurping control of this force from Gerard, who had just been wounded in the heavy fighting at the mill and not paying attention to his cavalry element.

Pajol arrived in front of Limal in the late afternoon or early evening. There was still plenty of light left to see that, while guarded by a sizeable quantity of infantry, the bridge was still intact and not barricaded. He accordingly formed the 6th Hussars into a column four troopers wide so as to be able to pass the bridge, and launched them into a charge with himself in the lead. The Prussian 19th Infantry Regiment had suffered severely in the defense of Ligny village two days before and was treating its out-of-the-way deployment as a kind of convalescence. The Prussian were not expecting what happened next.

Though taking on an entire battalion, the audacity of Pajol's charge was overwhelming. The infantry was cut to pieces. The other two battalions of the 19th Prussian Infantry Regiment were thus forced to yield as the rest of Vallin's cavalry swarmed across as well as Teste's infantry and Soult's cavalry divisions. Major Stengel, who commanded the 19th, fell back to the heights surrounding the farm of LaBourse. Thielemann ordered his whole line to shift down to the right while Stulpnagel and Hobe were sent to assist Stengel in an attempt to retake Limal and drive the French back across the river. The battle raged around the farm until well into the twilight hours when Grouchy arrived with the divisions of Vichery and Pecheux, turning the tide in the favor of the French.

It was now completely dark. In spite of this Stulpnagel arranged five of his six battalions for a counter attack. He ordered them in two waves, two battalions to the front and three in support, his sixth battalion in reserve. His first wave blundered ahead in the dark until it was stopped by a sunken road. Just as the troops began to cross this obstacle two battalions of French infantry sprang out of the darkness at the other side. Their tiraillade caught the Prussians in mid-passage and halted their progress.

Unable to withdraw because of the press from their rear ranks, a great number of Stulpnagel's men were shot down. The other three battalions in the second line had sidled off to the their left but they too encountered the French line. Both sides blasted away at one another's muzzle flashes in the darkness. Eventually Stulpnagel's first two battalions gave way, melting into the night. With their right uncovered the other three battalions of the second wave had to withdraw.

On the extreme right Stengel attempted to turn the French line with the remnants of the unfortunate l9th Regiment but they were ambushed by French cavalry. Compelled to retire, dawn (3:30 a.m.) found Major Stengel leading his men away from III Corps in the direction of St. Lambert in search of Ziethen's I Corps and his own brigade (Henkel). Stulpnagel withdrew also but regrouped his men in the Bois de Bierges.

There was still gunfire to be heard at Limal until just before morning, but the terrific cannonade from the west had long grown silent. It would not be until the next day that Grouchy, to his horror, discovered the meaning of this silence.

Order of Battle: Wavre (text only: fast load)

Order of Battle: Wavre (graphics: slow load)

Order of Battle: Limal Bridge (text OB, map graphics: fast load)

Order of Battle: Limal Bridge (graphics: slow load)

About the authors:

Ed Wimble describes his interest in Napoleon

and the Waterloo campaign as "a life-long

passion." More than a dozen years of research,

including four trips to the Waterloo area,

culminated in a series of five board games

about the campaign published by Wimble's

company, Clash of Arms. He is a member of

both the Napoleonic Society of America and the

Association Belge Napoleonienne.

Matt DeLaMater is the managing editor of

Napoleon Magazine.

Selected Bibliography

Bowden, Scott, Armies at Waterloo. Chicago: Emperor's Press, 1983.

The best source for order-of-battle information.

Becke, Major A.F. Napoleon and Waterloo: The Emperor's Campaign with the Armee du Nord 1815. London. Keegan Paul, Trench, and Trubner, 1939.

An excellent and rare work. I understand that this work will soon be reprinted.

Freidrich, Rudolf v. Befreiungskrieg 1813-1815. Vol. IV. Berlin: Mittler and Gohn, 1910.

The maps in this are excellent.

Houssaye, Henry. 1815 Waterloo. Felling: Worley Publications, 1991.

This book is a real treasure.

Kelly, W.H. The Battle of Wavre and Grouchy's Retreat. Felling: Worley Publications, 1993.

Reprint of 1905 work.

Lettow-Vorbeck-v. Voss. Napoleon's Untergang 1815.

Linck, Anthony. Napoleon's Generals: The Waterloo Campaign. Chicago: Emperor's Press, 1994.

We relied heavily upon this for our biographics of French Generals. An informative and entertaining resource book.

Ropes, John Codman. The Campaign of Waterloo: A Military History. New York: Scribner's, 1893 and reprinted, Felling: Worley Publications, 1995.

A superior analysis. A must if you are serious about examining the decisions in this campaign.

Uffindell, Andrew. The Eagle's Last Triumph: Napoleon's Victory at Ligny. London: Greenhill and Harrisburg: Stackpole, 1994.

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #1

Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Press.