My latest project is a recreation of the Battle for Fort George in May 1813. This War of 1812 battle is characterized by a near flawless execution of an amphibious landing and a hard fought land fight. As is my usual method, first I will recount the historical battle and then discuss some issues for solo consideration. Finally there is an order of battle and some uniform notes. Part two of this article will describe the rules I use to refight this battle in a solo mode.

The Historic Battle for Fort George - 27 May 1813

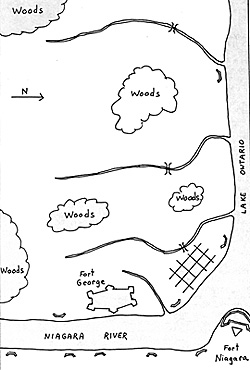

In May of 1813, the Americans tried once again to invade the Niagara peninsula (the attempts in 1812 were debacles). Commodore Isaac Chauncey carried Major General Henry Dearborn's army to Fort Niagara at the mouth of the Niagara River. Across the river, at Fort George, Brigadier General John Vincent prepared for an inevitable assault. However, Vincent could not tell if the impending attack would come across the river (as in 1812) or if the invading Americans would land on the shores of Lake Ontario. His slender force was spread thin to react to either eventuality.

Fort George itself was a wooden picket affair with six bastions and two interior block houses. The British had built several earthen batteries along the Niagara River and guarding the lake shore. Vincent divided his force into three pieces. His right wing, under Lieutenant Colonel John Harvey, guarded the river shore from Fort George south toward Queenston. His left wing, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Myers, protected the river shore north to its mouth and west along the lake shore. Vincent retained control over the garrison of the fort and a slender reserve. He could send reinforcements to either flank as necessary.

The land around Fort George and the small village of Newark was relatively flat. The banks of the rapidly flowing Niagara river were very low. A skilled pilot could guide a bateaux full of troops and land easily if he managed to dodge the heavy cannon fire that would spew from the many earthen batteries along the river. Along the lake shore, the beach area was very narrow and the cliffs varied in height from six to twelve feet thus presenting an obstacle to the assaulting foe. The fields behind the shore were flat except for the beds of streams which fed the major creeks entering the lake. These stream and creek beds lay at the bottoms of shallow ravines which did not present an obstacle to movement but in fact concealed anyone in the ravine from observation from the lake. The British and Canadians would use these ravines to good effect to protect themselves from naval gunfire.

Planning the Attack

The Battle for Fort George marked the high point of American Army-Navy cooperation during the War of 1812. Chauncey and Dearborn met with their key subordinates to plan the attack. A key player was Colonel Winfield Scott, commander of the 2nd Artillery and currently serving as

Dearborn's adjutant. Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry, hearing that Chauncey had brought the fleet to Fort Niagara in anticipation of a move on Fort George, departed his ship building activities in Erie, Pennsylvania and hurried eastward to get in on the action. The presence of Scott and Perry added audacity to the planning process.

Chauncey and Dearborn decided on an assault from Lake Ontario. This would take advantage of the U.S. Navy's considerable firepower advantage that could not be brought to bear in support of a river crossing. The assault force was divided into an advance guard and three assault brigades arriving in sequence. The object was a direct move from the beaches to Fort George. Scott was given command of the vital advance guard, the first soldiers to hit the shore. Perry directed the placement of buoys in the lake waters to mark the position of each major vessel so that fires could be delivered against the defending British without interfering with the landing boats. Enjoying overwhelming strength, the Americans anticipated that the British would evacuate Fort George rather than defend it. Therefore, Dearborn directed his dismounted dragoons to cross the Niagara River south of Fort George to cut off the British escape route. From Lake Ontario, the ships' guns could not reach Fort George itself, but those American guns along the Niagara shore could. Therefore, Dearborn ordered a general bombardment of Fort George to soften up the defenders prior to the assault.

The Opening Bombardment

On 26 May, the Americans opened a furious cannonade of Fort George and the batteries defending the western shore of the Niagara. The British returned fire as best they could. Using hot shot from a couple of guns, the Americans managed to set several fires inside the fort eventually rendering the blockhouses useless as defensive works. Because of the volume of American cannon fire, Vincent ordered the garrison from Fort George except for the gun crews. The defenders slept fitfully on their arms in a meadow outside the fort that evening, in expectation of an assault from any direction.

The Assault

The following day opened with a heavy mist on the lake's smooth waters. As the mist cleared, the British were treated to the spectacle of the Lake Ontario squadron positioned close to shore and more than one hundred troop-laden bateaux approaching shore. Both sides opened cannon fire, the British from a single 24# gun in a battery near the lighthouse and the Americans from every vessel. Lieutenant Colonel Myers had his men in the protection of ravines as close to the shore as possible. Whenever they attempted to reposition themselves, they drew the concentrated fire of grape and solid shot from the American fleet. Perry was everywhere. Rowed about in a small craft, he moved from ship to ship directing the gunfire to the best advantage.

The American infantry, in even waves, moved relentlessly toward shore. At the last possible moment, Myers ordered his men to leave the protection of the ravines and meet the Americans on the shore. Hardly had Scott and his advance guard landed when they where met by the fire of the British along the top of the cliff. Returning fire, the Americans clawed their way to the top of the banks. Dearborn, watching from shipboard, saw Scott reach the top of the cliff only to be toppled backward onto the beach. Presumed dead, Scott thrilled the watching Americans by regaining his feet and once again pushing to the bank top.

Unable to hold them at the water's edge, the British withdrew a few hundred yards and formed a firing line. Scott's advance guard formed line in similar manner and commenced a furious exchange of musket and rifle fire. Eventually Brigadier General Boyd landed his men and brought them into action on Scott's left. Lieutenant Colonel Myers was felled, shot three times while leading his men. Numbers told and after fifteen minutes of exchanging fire at fifty yards or less, the British were forced to withdraw leaving half of Myer's brigade dead or wounded.

As Myer's command retreated, they were rallied by Harvey who brought up several companies of the 49th Foot and a six pound gun. Positioned in a ravine, the British contested the American advance but Harvey saw that he was being outflanked by American riflemen on his left and infantry on his right. He withdrew his command to a third ravine to continue the unequal contest. Again threatened by Americans moving up on both flanks, Harvey withdrew to the open area immediately west of the fort where Vincent took command. Meanwhile, the Americans were deliberately moving their forces to encircle the fort. Learning that the dismounted dragoons were even then crossing the Niagara south of the fort, Vincent ordered Fort George evacuated and the remains of his command to withdraw inland.

The British retreat was executed quickly and the Americans, still trying to maintain their organization and encircle the fort, could not do so before Vincent's troops and some guns made good their getaway. Scott, acting on his own, lead the advance guard and went off in pursuit. While capturing stragglers, he could not regain contact with Vincent's main body before being ordered to return to Fort George. When word of the fall of Fort George reached British troops and militia, they abandoned the line of the Niagara and withdrew inland after destroying what stores they could not take with them. Much hard fighting remained along the Niagara in 1813 but to some small extent, the Americans had redeemed themselves from the particularly poor showing of the previous year.

Considerations for Solo Play

This battle was unbalanced and the best the British might have expected was to inflict heavy casualties while still escaping to fight again. My sympathies with the underdog, I command the British and Canadians while automating the Americans. However, I beef up the British by giving them more Glengarries and Lincoln militia just to make the fighting more interesting.

In automating the Americans, there is really only one issue - how will they attack. Dearborn had several courses of action open to him. He could have made his main attack across the lake with a small supporting attack across the Niagara (the historical solution). Alternately, he could have made his main attack across the Niagara supported by a small landing on the shores of Lake Ontario. And a third option, two equally-sized attacks across both river and lake. The goal of the Americans is to surround Fort George so as to capture Vincent's entire force. Of course, it is extremely difficult to coordinate two simultaneous attacks and the British can defeat one attack on the shore before the other one lands. Likewise, the vagaries of weather and other factors may mean that the Americans can't land everyone in a timely manner allowing them to be defeated piecemeal. In part two I will lay out the rules I used to automate the American attack as well as describe my refight of this historic battle.

Order of Battle

The sources are contradictory on which units participated in which higher organizations nor is there agreement on unit strengths. The following is an educated guess.

British Order of Battle

Commander: Brigadier General John Vincent

Right Wing: Lieutenant Colonel John Harvey

- 49th Foot (200 in 7 coys)

1 six # field gun

5 batteries with 6 guns and 5 mortars

Left Wing: Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Myers

- 8th Foot (300 in 5 coys)

Royal Newfoundland Fencible Infantry (40 in 1 grenadier coy)

Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles (110 in 2 coys)

2nd Lincoln Militia (170 in 2 flank coys)

Captain Runchey's Militia Company (30)

Captain Norton's Mohawk Company (50)

Lincoln militia artillery detachment

1 battery with 24# gun

Forces under BG Vincent's direct command:

Detachment in Fort George under Colonel William Claus:

- 49th Foot (30 in 1 coy)

Royal Newfoundland Fencible Infantry (70 in 2 line coys)

4th Royal Artillery Battalion (58th Company of 26 gunners)

1 twelve # gun

2 twenty-four # guns

2 mortars

artificers (90)

Cavalry:

- Provincial Dragoons (AKA Niagara Frontier Guides) (30 in one troop)

American Order of Battle

Commander: Major General Henry Dearborn

Second in Command: Major General Morgan Lewis

Advance Guard: Colonel Winfield Scott

- Left: Lieutenant Colonel George McFeely

22nd Infantry (100 in 2 coys)

23rd Infantry (100 in 2 coys)

Center: Directly under Scott

- 15th Infantry (100 in 2 coys)

2nd Artillery (100 in 2 coys)

3rd Artillery (50 in 1 coy)

1 three # gun

Right: Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Forsythe

- Rifle Regiment (400 in 6 coys)

1st Brigade: Brigadier General John Boyd

- 6th Infantry (300)

15th Infantry (200)

16th Infantry (300)

McClure's Battalion of Rifle Volunteers (100)

2nd Brigade: Brigadier General John Chandler

- 21st Infantry (300)

23rd Infantry (300)

25th Infantry (300)

3rd Brigade: Brigadier General William Winder

5th Infantry (300)

13th Infantry (300)

14th Infantry (300)

Fort Niagara:

- 22nd Infantry (200)

2nd Light Dragoons (150, mostly dismounted)

6 twelve # guns

2 nine # guns

1 mortar

Five batteries along Niagara River

- 2 eighteen # guns

5 twelve # guns

4 six # guns

2 eight inch howitzers

3 mortars

Uniform Notes

American Army:

In May 1813, the recent uniform changes were slowly being implemented and there is no hard evidence that the troops received new issues prior to the campaign. Most likely the 1812 pattern wool coats and gaiter-trousers issued during the previous winter were still being worn. The new leather "tombstone" shako was approved in February and the War Department gave priority of issue to the regiments in New York. However, like the coats, it is probable that the cylindrical felt shako with white plume in the front was still being worn.

The following uniform particulars are likely.

- 5th, 6th, 13th, 21st, and 23rd Infantry: 1812 pattern - blue coats, red collars and cuffs, white tape on chest, cuffs, and collar. Wool pants of gray, brown, or drab. Musicians in reverse colors.

14th Infantry. Brown coats, red facings.

15th Infantry. Gray coats, red facings. Trousers gray or white.

16th Infantry. Black coat faced red.

22nd Infantry. Drab coats faced green. Black lace. Musicians green coats faced drab.

25th Infantry. 1812 pattern but no white lace on front of coat.

Rifles. 1812 pattern. Green coat, black facings, yellow tape. Green gaiter-trousers.

McClure's Rifle Volunteers. These two companies came from Albany and Baltimore. It is quite likely that they wore the regular riflemen's summer pattern which consisted of green rifle frock. Maryland units preferred red fringe while New York units were partial to yellow fringe. Trousers might be green wool or white linen. Either shakos or civilian style cylindrical "round hats" with yellow or green plumes and cording were likely.

Artillerists. 1812 pattern coats had longer tails than the infantry pattern. They had red facings and yellow tape at collar, cuff, and across the chest. Trousers were white with yellow piping. 1st artillery retained the "chapeau bras" but the 2nd and 3rd artillery wore the shako with yellow cords and white plume. The chapeau bras is a "fore and aft" hat worn by British and American field grade and general officers; think Wellington.

Dragoons. 1812 pattern short blue coats and trousers. Coats had white tape on collar and cuffs. The helmet was of black leather with black comb holding a long, flowing, white horsehair crest. Because they fought dismounted, they carried muskets but left sabers and pistols back in Fort Niagara.

British and Canadian Forces

The 1812 uniform changes (belgic shako, gray trousers etc.) were only partially implemented in Canada by May 1813. It is unlikely that any of the troops had the belgic shako however most units almost certainly replaced their white breeches and black gaiters with gray trousers. The following particulars are of interest.

- 8th Foot. Blue facings.

49th Foot. Green facings.

Royal Newfoundland. Blue Facings.

Lincoln militia. The flank companies received priority for uniforms. This was identical in cut to the regular uniform but the coat was dark green faced red with the usual white lace.

Glengarries and Runchey's company. These troops wore the standard British rifle uniform although trousers might be either gray or green. However, the soldiers carried muskets, not rifles.

Provincial Dragoons. Most likely single-breasted short blue coat faced red. Leather helmet (Tarleton style) with bearskin crest. Gray riding trousers.

Mohawks. John Norton's warriors fought in traditional Indian garb (breech cloth, leggings, moccasins, bare chest or civilian style shirt with ample war paint). Most used muskets and carried tomahawks and scalping knives.

Back to MWAN #95 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com