In his brilliant book, Julius Caesar, Man, Soldier, and Tyrant, J. F. C. Fuller says, "An infantry army particularly in which battles were hand-to-hand contests, was a simple force to command. So much depended upon drill, upon the maintenance of an unbroken front and ability to replace quickly and without confusion an exhausted front rank by a fresh rear rank, that any good drill-master was a good general." (p. 74). In Tony Bath's seminal Setting up a Wargames Campaign, he says (referring to the Peloponnesian War), "The disadvantage of this particular war is of course that the land battles were almost exclusively fought by armies of hoplites; light troops were used to some effect on special occasions, such as at Sphacteria and in Boetia, and cavalry in the Syracuse operations, but normally it was a heavy infantry affair, which tends to make a somewhat boring wargame." (p. 5). In the original version of William Banks' game Ancients (now published with two different collections of scenarios by 3W) he notes that in the Viking baffle of Ashdown he has added some archers and cavalry to "liven things up," (the implication being that Bath is right and a battle that is simply an infantry melee is boring).

Finally, in a book published in 1980 by the editors of Consumer's Guide, two GDW games receive comparable remarks: concerning The Battle of Raphia they say "Ignoring most of the other terrain, the two sides set up facing each other in the center of the map, and then it's hack and slash, as two lines of units dice each other to death," and about Pharsalus, "Despite much chromatic machination, most ancient battles tend to look and feel alike... like all ancient battles, the affair is limited in maneuver and heavy on shock."

Heavy Infantry Battles

Do battles between heavy infantry make for tedious and uninteresting games? I've not done much with Tactica, but it seems to me that most of the armies designed to fight each other differ enough to provide variety. The only real line up with hoplites as the main force for both sides seems to be Spartans and Thebans and even here the special characteristics of the deep Theban array and the Sacred Band make an interesting situation (though I must confess, the only time I gamed it, the battle was decided by a fluky cavalry victory). I have done even less with Armati, but suspect that a Spartan-Theban face off there might be somewhat less interesting than in the earlier rules.

My own rules for the Peloponnesian War are based around the concept of the importance of the heavy infantry maintaining their formation (as implied in the opening quotation from Fuller). I decided to try them out in some scenarios from the Peloponnesian War, beginning with First Mantinea, a battle fought in 418 B.C. with Sparta and her Tegean allies ranged against Mantinea and Argos who were supported by a small Athenian contingent. It is the most completely described battle of the war and therefore the one about which there is the greatest confusion. In spite of the uncertainties about the battle and the Spartan intentions, it remains the best example of a Spartan victory in a "classic" hoplite battle.

Since Thucydides calls it the largest battle between hoplites up to that time, I decided that I had best make maximum use of the hoplite figures I had. Working from the estimates of strengths Donald Kagan's The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, I ended up with a figure ratio of 1 figure representing 107 men, not far from the notional scale of 100-1 for the big battles in the "Sparta's Wars" rules.

From this I extrapolated non-hoplite strengths. Since my hoplites form up three deep (except for the six deep Thebans who were Sparta's allies at the time of Mantinea but who did not arrive in time for the battle) I made all hoplite units divisible by three. On occasion this meant combining some contingents from minor powers or subdividing large armies into contingents (as we know the Spartans, at any rate, actually did). In any case, I ended up with the figures given below as close scale approximations of the actual forces in what looked to be provide a situation that did seem to favor the actual victors but I hoped would not be too unbalanced.

Terrain

The terrain around Mantinea was important in the campaign, but the battle itself seems to have been fought in the open. The Spartans were deployed roughly facing northwest with their backs to Pelagos Wood. The Mantineans and their allies were opposite them with their backs to the city of Mantinea (apparently much further from it than the Spartans were from the wood). What was important in the battle was not the terrain, but a peculiarity of the deployment. This is the battle in which Thucydides discusses the tendency of armies to drift to the right as each man seeks protection for his unshielded side from the man on his right. If those who interpret Xenophon's descriptions of Nemea and Coroneia as being intentional marches to the right flank are correct (as J. K. Anderson has convinced me that they are) this reference is the only one in any writings from the entire ancient period to suggest that this occurrence was a natural and unintended one.

That large armies did "accidentally" drift to the right has been widely accepted, partly because of Thucydides' reputation and partly because it does make sense, as the man furthest to the right would tend to edge a bit to his unshielded right and each man down the line be inclined to veer in accordance, seeking some shelter behind the shield of his right hand neighbor. In an earlier version of the rules for this period I included this tendency to drift to the right in the movement of hoplite lines.

Veering to the Right

What I did was determine the likelihood of a veer to the right by a die toss modified by the unit's drill. The Spartans (being the most drilled troops in the era of the Greek city-states) were likely to veer the least and poorly drilled units (the bulk of the forces of most armies) being likely to get quite off course. This inclined players to place their best units on the right flank, since units could not veer more than their right hand neighbors did. I liked this since the practice in this period was to place the best units on the right (the place of honor--"the spear hand") and the rules thus encouraged players to follow contemporary procedure--not because of some special deployment rules, but because it made sense in terms of the rules system. The main reason that I decided to omit this mechanism was a point made by Chris Engel--that it seemed the sort of thing that players, in the excitement of the game, would be likely to forget (I did appreciate his suggestion that the players might in fact get excited playing a game using these rules).

The other reason that I dropped it (besides a desire to fit the rules onto an 8 1/2 X 11 inch sheet of paper) was that I began to wonder whether or not it was even true that large armies did inevitably move in this way or if it would have occurred in every battle.

In any case, according to Thucydides, it had an effect on this one. Each advancing army outflanked its opponent's left. The Spartan king, Agis, ordered his left flank unit (composed of Sciritan allies and the "Brasidoi"--former helots who had been freed and equipped as hoplites) to move left to position itself opposite the enemy unit on the right. They did so and he gave orders to some of his Spartan units to close the gap. Thucydides says that these Spartan units were to come from the right. This apparently does not mean the far right since he says that it was held by the Tegeans "supported by a few Spartan (emphasis added).

On the other hand, if he meant simply that the units immediately to the right of the Sciritai and Brasidoi should take ground to the left, why specify that the units were to come from the right? My own suspicion is that Thucydides is in fact referring to the Spartan units to the immediate right of the Sciritai and Brasidoi and that, as the enemy continued to close as the Spartans maneuvered, the commanders of the units involved decided that it was too risky to expose their unshielded sides by moving to their left. Since the orders were not carried out, however, it remains an unsolvable mystery.

Isolated Unit

In any case, the isolated unit of Sciritai and Brasidoi was overwhelmed (being outnumbered and outflanked) while the Spartans went on to defeat the opponents opposite them (who were also outnumbered and outflanked). It was here that the superior training of the Spartans evidenced itself. The Mantineans and elite Argives, having won their melee but finding the Spartans in their rear, seem to have had no idea what to do and panicked, hurrying back toward their camp.

Theoretically, the Spartan army was in the same predicament, but seems never to have panicked but remained calm and well in hand--ready to obey orders and maneuver on the battlefield. They formed up perpendicular to their original deployment and as their foes streamed across their front (exposing their unshielded sides) they slaughtered them as they ran.

Whatever the difficulties and intentions of the opposing sides were, terrain does not seem to have played a part. What was important, if not decisive, was the gap between the Spartan's left most unit and its nearest neighbor on the right. Thus I deployed the Mantineans with 1/2 inch intervals between units. There seemed no good way to duplicate the process by which the gap developed in the Spartan front, so I simply deployed them according; opposite the Mantinean right placed the unit of Sciritai and Brasidoi with a 5" gap before placing the remainder of the Spartan force (which then had 1/2 inch intervals between units).

I divided the Spartan cavalry into two tiny detachments. There should have been about 400 Spartan cavalry to 300 Athenian cavalry (no other cavalry is mentioned in the anti-Spartan alliance), but the actions of the Spartan horse are not mentioned. Since Thucydides does say that the Athenian cavalry was able to protect their retreating infantry, I decided that this was more likely 'they had local superiority. Probably there were, in addition to the cavalry, some light troops of some kind, but they are never mentioned and seem to have had no effect on the battle.

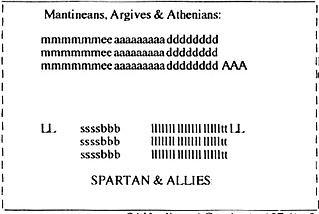

Deployment for the Battle of Mantinea (418 B.C.)

(Total = 8346)

Right to Left:

Unit of 24 (Mantineans & Elite Argives opposite Sciritai & Brasidoi)

Unit of 27 (Argives)

Unit of 24 (Delian League --Athenians & Allies)

Unit of 3 (Athenian Cavalry)

SPARTAN & ALLIES: 84 Hoplites, 4 Cavalry (at 107-1): 84 = 8988 Hoplites 4 = 428 Cavalry (total = 9416)

Right to Left

Unit of 2 Cavalry, Unit of 21 (Sciritai & Brasidoi), 5 inch gap before next unit

Unit of 21 (Spartans), Unit of 21 (Spartans), Unit of 21 (Tegeans & Spartans)

Unit of 2 Cavalry

My opponent in this action was my good friend (and fellow Patrick O'Brian enthusiast) Francis Lynch. So far in every historical action we have fought, the results have been remarkably accurate: his Colonel Morgan humiliated my Colonel Tarleton at Cowpens and his Admiral Jervis humiliated my Admiral de Cordova at St. Vincent. His General Greene did manage to hold the field against my General Cornwallis at Cuilford Courthouse--but a single die toss would have made for historical result--a comment on how close the action was and how much the British victory was actually a defeat. Should our history of history repeating itself repeat itself, our initial toss for sides should have determined the winner.

In the toss for sides, I got the Spartans and therefore had to win. The movement toward each other proceeded with little of interest occurring (no light troops to do anything) and then the lines met and we started grinding into each other. I generally seemed to have the edge (better dice) the melees between formed troops, but he had magic dice in two categories: he never lost a movement toss and he was devastating in the rough and tumble melees that occurred when both sides lost their formations.

The first may not seem like much, but it meant that I was never able to take advantage of an enemy unit losing formation--they fell back out of contact and were able to reform. For an example of the second, I will point out a very interesting episode between the Brasidoi and their opponents. The Brasidoi actually managed to win the initial action, but both sides were soon reduced to forces too weak to reform--to be precise, the Brasidoi had 11 men and their opponents 10 in the first round of unformed melee. In the second turn of unformed melee each of the surviving Brasidoi was outnumbered 2-1. In the next turn of melee, their single remaining trooper was cut down.

To add to my bad day, there was a unit flanking the hole in the Spartan line which broke (just like really happened), but rather than being the despised Sciritai and former helots of the Brasidoi, it was a unit of all Spartan troops--what will they say at home? Nevertheless, the unopposed Spartan unit on the right flank was able to carry out its wheel and begin closing in on the outnumbered enemy (though held up for a turn or two by some pesky Athenian cavalry that refused to run away and decided to die hard).

We ended with a bloody Spartan victory won by hard fighting and superior numbers rather than by superior generalship (though the Spartans did maneuver on their right flank). Was it boring? It wasn't boring, but it did seem to have more of a sense of trying the rules out rather than fighting a battle. May be next time we will play the perfect game.

Back to MWAN #88 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com