Welcome to the second edition of Going It Alone, a column for those interested in solo wargaming. Last issue I promised to address 18th and 19th century fighting in the forests of North America. True to that promise, here it is.

For those who saw The Last of the Mohicans, who can forget the ambush scene. A column of British regulars and their camp followers and provincial militia with their families are under a pledge of safe conduct to retum to British-controlled territory. However, the diabolical French commander has agreed to look the other way while his native allies attempt to gain the trophies and glories of war that the surrender has deprived them of.

The long column enters a clearing when it is attacked by natives. At first, individual Indians display their bravery by attacking singly. Then the great mass of red men sweeps out of the wood line and charges the column at a dead run. Unorganized musket fire fails to stop the whooping horde as it closes with the stunned and stationary British and Americans. The fight degenerates into man-to-man fighting - European musket against Iroquois war club, bayonet against tomahawk, pistol against scalping knife. The frantic orders and high-pitched war cries mix with the screams of the dying! Red warriors cutting out the hearts of their fallen foe. Blood everywhere! Watching the screen, his heart pounding, his palms sweating, the solo gamer asks himself "How can I model this good stuff?"

Well, I can't help with that question in its entirety but I can offer a methodology that recreates some of the unknown. This column will show the diligent and studious war gamer how to generate a long stretch of forest terrain and some ideas on how to trigger incidents that must be dealt with. First, let's look at a North American forest.

Forest from Trees

Primeval is probably a good descriptive word. In most places forests were mature with tall trees blocking out much of the sunlight to the ground below. Because of lack of sunlight, there was lime undergrowth. Nevertheless, walking was not easy. Coniferous trees left a thick bed of needles on the ground and deciduous trees dropped their leaves.

Fallen trees took years to decompose and their rotting remains fommed obstacles to movement. Deer and other critters cut some paths and these frequently led to water. On the verges of the forest, there was enough sunlight to support thick undergrowth which slowed movement to a crawl. In some places, natives wore their own paths as did European settlers who may even have widened the trails to accommodate horses and wagons.

These North American forests covered many types of terrain: flat, rolling, hilly, and even mountainous. Besides being cut by numerous creeks, forests were speckled with small ponds and clearings. And from time to time would appear a native village or settler's cabin, particularly near the forest edge.

The characteristics of the forest require special rules. The following are areas in which you may want to adjust your rules.

Visibility is limited. Targets can be acquired only at close distances and even then the viewer will get a distorted and incomplete picture. Two hundred native warriors may lie in ambush but the scout only sees the movement of a branch. That is enough to warn the column but the commander won't stop marching for every swaying bough.

You may want to model two things here. First, as you approach an enemy force, roll to see at what distance you acquire an indication of enemy activity. Second, roll to see if the commander takes the warning seriously enough to stop the column while he sends a party forward to check out the evidence. Remember, the astute commander on a planned march had scouts (e.g. natives, rangers etc.) far in front of the column as well as close in scouts and advance, flank, and rear guards.

Movement is at a crawl. Even if the main column is on a trail, the flank guards and scouts are not. They are scrambling over fallen trees and around rock fommations as they check out potential ambush sites. The column can only proceed at the speed of the slowest element which may be an ox-drawn ammunition cart. Every stream is an obstacle to a wagon.

Formations are distorted. Even if the trail is wide enough to allow three soldiers to walk abreast, a battalion of troops is two hundred yards long or more. This means gathering the force together to offer strong resistance is problematic as it will take time. In theory the commander would want to fomm lines or even a closed square but he has a long, slender column to work with.

Every formation formed in a hurry will have some bends and breaks in it. And if the enemy can close to hand-to-hand combat quickly enough, that portion of the friendly force is fixed until it can defeat the enemy at hand.

Command and control is extremely difficult. For reasons stated already, the commander will probably not get a true understanding of the threat until too late. Nevertheless, he may order some type of reaction (form line or square, defend or attack) before the actual situation is understood. Then he must get this order up and down the column to be implemented. Not everyone will hear his voice clearly enough. The best forest fighting commanders designed drills and rehearsed them so that upon hearing an order, the various companies passed the order and reacted quickly to implement it.

This effects the ambusher too. He undoubtedly has briefed his subordinates on the ambush plan. But what if the ambush is discovered before the column completely enters the kill zone? How does the ambusher signal a change of plan? Roll to see if the enemy can implement a change in orders. If he can't, then the ambush may degenerate into numerous small melees with much of both forces out of contact for awhile. Even if can successfully issue new instructions, it will take some time for the war parties to redeploy

Cover is dense. Big trees stop bullets and arrows. (Duh!) The effectiveness of missile weapons needs to be greatly diminished, perhaps by as much as 75%. The implication of this is that most casualties will result from close in fighting so ensure that your rules are comprehensive enough to resolve bar room brawling. Remember, a bayonet on the end of a musket can be a match for war club or tomahawk. The officers' swords were most effective.

Native warriors did not fight the way Europeans did. (Readers insert your sarcastic rejoinder here.) They fought in a variety of modes regardless of the orders received. Small parties of young warriors might charge larger bodies for the purpose of proving manhood. Older, wiser warriors, having established their manhood on earlier battlefields may be inclined to remain at a distance exchanging missile fire.

Having taken a scalp or captured a weapon, some warriors will drop out of the fight. having accomplished their most immediate goal. The European commanders will be frustrated beyond measure if they are not expecting this wide variety of response to their orders. Roll for each war band to see how closely it responds to orders. If it fights a successful engagement, roll again to see if it presses the fight or takes a break to admire the trophies accrued.

Morale. While properly not a characteristic of the North American forest, it is nonetheless critical to fighting in a forest. Because the European and provincial troop will not see the enemy until he charges out of cover at close distance, he is extremely susceptible to paralysis from war cry.

Many accounts tell of the inexperienced regular or militia man who cowers under a fallen tree or runs rearward at the first native whoop. This is particularly true if the ambush is sprung at one end of the column and the troops elsewhere do not know what is happening nor have they received orders. Scalpless men, fleeing the battle, running through the ranks trying to escape will usually cause the morale of the uncommitted unit to degrade a level or two.

Only the best, most trusted and confident officers will maintain control until orders are received. And on the other hand, some provincial troops were so inspired by revenge that they could hardly wait to get into a fight with natives. The Tennesseans and Kentuckians in the War of 1812 come to mind.

Okay, there is a synopsis of the environment we are working in. Now, how do we "generate a long stretch of forest terrain" I mentioned earlier?

TERRAIN

I like to wargame 25mm figures on a 4 by 8 table so the description which follows is adapted to that size. However, the method is workable in any scale. This method is not entirely original with me but I don't recall where I first saw it.

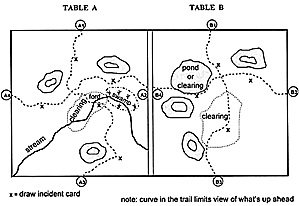

I begin by dividing the board into two equal squares with a piece of tape. All terrain is considered forested except clearings and ponds which are pieces of appropriately colored paper taped to the board. Streams and trails are drawn in. The only other terrain feature are small hills. I imagine you can designate impassable terrain such as rock masses although I have not done this.

Okay, now let's see what we have. Let's say our scenario calls for a movement of a column through the forest. The mission is to reinforce a small outpost. Now we want to generate a route through the forest. Let the column enter Table A at Al. There are only three places to exit the table; they are A2. A3. and A4. Roll a die to see where the column exits. Record the result.

Now roll to see where the column enters Table B for the second leg of the journey. There are four possibilities. Roll for where the column exits Table B. Keep doing this until you have generated a course long enough to sustain the game you envision. Notice that on Table B one of the areas is marked pond or clearing. Each time you enter Table B, roll to see which form of terrain that area will be. Place the objective, in this case the outpost, in the clearing on the final table you visit. The results of this route generation might look something like this.

| Leg of Journey | Table | Enter | Exit | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | A | A1 | A4 | - |

| 2nd | B | B3 | B2 | area is pond |

| 3rd | A | A4 | A2 | - |

| 4th | B | B2 | B1 | area is clearing |

| 5th | A | A2 | A3 | - |

| 6th | B | B4 | B3 | area is clearing; outpost is in large clearing |

The x's mark places where you will draw incident cards. Sometimes the incidents are blanks. Sometimes they are enemy contacts and sometimes they are problems with the column. Each incident (other than blanks) should have an event as well as a result. The following are some examples.

-

1. Right flank guard slows to half speed for two turns; commander only learns this on

third turn following incident.

2. Advance guard runs into small party of the enemy who get the first shot off et the startled troops.

3. Large enemy force on top of nearest hill mass starts movement toward the center of the column. Commander not made aware of this until enemy closes on friendly troops.

4. Scouts report a stationary body of the enemy up ahead 300 meters. They did not see your scouts.

5. Enemy force directly north of your column and 200 meters away. They are approaching as fast as they can.

You get the idea. Incidents should be of a nature to cause the commander (you) to decide on continuing the present course of action or to change it in response. Use your own system tor generating the composition and the posture of the enemy. Lone Warrior magazine is full of methodologies to do this. You will probably want the enemy operating in a number of smaller units; this allows some variation in how each unit acts.

The fun part. to my way of thinking, is to generate a scenario and to come up with some victory conditions. I have come up with a few set in the context of the War of 1812 and based on historical incidents. Hope they give you some ideas.

Scenario 1. A US column consisting of five companies of regulars, two of rifle volunteers, and one of regular riflemen is sent to raid a small settlement known to be a center of Canadian militia activity. Canadian militia (mounted as well as dismounted) are known to be operating in the area but a brigade of British regulars augmented by an unknown number of native allies was reported to be twenty miles away two days ago.

Scenario 2. A British force is ordered to move on an American frontier senlement and to burn the whiskey distillery and grist mill located there. The British force consists of four regular line companies, one each of grenadiers and light infantry, three companies of Canadian fencibles, a detachment of light dragoons, and native scouts. There are no American regulars in the area but if word of the raid leaked out, a very large body of rifle and musket equipped militiamen can be expected to intercede.

Scenario 3. Two companies of Royal Marines, three companies of Canadian fencibles, and a war party of native allies is sent to capture (best) or destroy (okay) a slow moving US supply column somewhere on the trail ahead of them. The composition of the US force is unknown but probably includes rifle volunteers, both mounted and dismounted.

Back to MWAN #87 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com