Welcome to Going It Alone, a column for those interested in solo wargaming. In this continuing column I hope to set forth methodologies and theory of solo wargaming for those historical gamers who want to expand their enjoyment of fighting skirmishes, battles, and campaigns. Most of the material presented in these pages will be at the entry level or intermediate level. Thus, I hope over time to have something for both the beginner and the experienced soloist.

Solo Wargaming, like many other fields of this great hobby, has its own journal. Lone Warrior is advertised in MWAN and is the quarterly publication of the Solo Wargamers Association, a group which supports soloists with ideas, advice, and other services. If concepts in this column strike your fancy, you can be sure that you will find more information in Lone Warrior.

To get started with, let's take a look at solo gaming. There are two ways to fight solo. The first is to command, deity-like, both sides. Initially satisfying, most soloists grow out of this stage when it becomes, as it eventually must, boring. Nonetheless, let me suggest that those of you who are trying to play by yourself for the first time give this a shot. Use whatever multiple- player rules you are comfortable with and go for it. If nothing else, it will give some satisfaction as well as expose you to the issues and problems of monogamous gaming. Then when you're ready, try commanding one side while "programming" your opponent.

Perhaps the central problem of solo gaming is how to simulate a foe who responds in a plausible manner to our activity and who, from time to time, takes the initiative. We want a foe who puts up a fight, who surprises us, who makes our ultimate victory satisfying and our infrequent defeats explainable. How do we get there? Well, that elephant needs to be eaten one bite at a time and thus is the basis for this potentially never-ending column. And, what is satisfying for a few games may eventually become tiresome. Thus the soloist is faced with the continuing problem of always wanting new techniques to extend his wargaming pleasure. Give him variety or give him a live but docile opponent who is always available at a moment's notice and doesn't get argumentative, win too frequently, or knock over his favorite figures!

I am unaware of any comprehensive set of rules which promises to simulate an enemy who will always excite the interest and engage the intellect of a solo gamer. There are just too many variables to be manipulated if the solo gamer is trying to create an artificial intelligence with whom he can battle. But there are countless techniques which can be tried, either alone or together, to see how well they fill the bill. The savvy soloist has his personal collection of rules and methodologies from which he custom designs his games. A place to start is by identifying those variables which the soloist wants to play with and then coming up with procedures and probabilities to create a situation (plausible yet unpredictable) which unfolds in a timely manner.

The Siegfried line

Let's use an example to see how this can be done. Let's say you just read a story about the U.S. Army trying to penetrate the Siegfried Line in late 1944. You have a burning desire to game the adventures of an American infantry battalion (you) fighting its way through the line (the programmed opponent). No, don't start by laying out the terrain and the German figures and pill boxes. Instead, think through the situation and try to figure out what you know about the situation. What you don't know is what you will try to contrive solo mechanisms to simulate.You know the composition of your battalion, the numbers of soldiers, their equipment, and theirlevel of training, moray:, and supply. You know your mission which you define as entering on side of the wargame table and exiting the other while clearing a path for follow-on units of some width, perhaps 800 yards. As for the terrain, your map tells you the general lay of trails and streams through the thick, dark, rugged forest. You know the general lay of ridge lines but the precise topography of hills, ravines, clearings eludes you. From your reading you know that squads sometimes lost track of their parent platoons and that only an exceptional company commander was certain of the whereabouts of his platoons at any given time. You can talk to your company commanders by radio most of the time but they communicate with their platoons by runners (who get lost). For fire support, you have the services of a battery of 75 mm guns. However, since none of your subordinates will ever be certain of their location, calling for fire will be literally hit or miss. The forward observers will try to bracket a target but to do so, the must see the strike of the artillery rounds, something which may not happen all the time.

As for the wily enemy, he has been in the line for several days before you arrived. His concrete pillboxes were constructed before the war and are now covered with natural foliage. He has sited his pillboxes to take advantage of corridors of fire through the woods created by selective cutting of trees. Unfortunately, your troops won't know they are in his field of fire until he opens up. The enterprising German opponent has strengthened his position by putting small minefields along probable avenues of approach and he has hidden barbed wire fences to hold you in his "fire traps." He reinforced his line with log bunkers which fire into the path of any troops bold enough to assault a pill box. He depends on the interlocking fires of his machine guns to protect the integrity of his line and platoon size counterattacks to restore the line if it is penetrated. He peppers the forest with squad-sized roving patrols and stationary ambushes. His artillery is registered on several points and therefore his ability to drop high explosive into a "fire trap" is a given. Thank the wargaming gods that there are a lot more of you than him.

This scenario presents the soloist with a large number of variables to deal with: type, size, and locations of terrain, obstacles, pillboxes, ambushes, and patrols for example. To that add friendly and enemy artillery fire, and communications between you (the battalion commander) and your companies and between them and their platoons. The experienced soloist may have a technique for each variable, but let's look at this from the perspective of a newbie. Our beginning soloist wants to limit the number of variables he has to deal with. The choice is up to him but let's talk our way through some thought processes. Let's first look at terrain.

Terrain

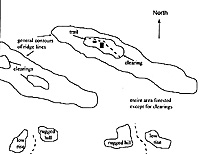

The solo gamer probably wants to lay out those terrain features that he would expect to have prior knowledge of from maps, photo recon, or recon patrols. For example, he places two long ridge lines on the table running diagonally across his intended direction of movement. The rest of the table is forested but photo recon revealed two small clearings on top of one ridge and a third, larger clearing atop the other. In the larger clearing is a small famm house and team with a trail visible across the clearing and appearing to run along the top of the ridge. The clearings are on the flat top of the ridge but the sides of the ridge may be either rugged or gentle rises. The gamer places two trails leading from his side of the table and extending a short distance into the forest. On each side of both trails he places small rises or rugged hills as he chooses. These would be known through reports from recon patrols. His infantry moves fastest along the trail, slower through the flat forest, slower still up the rises and crawling speed across the rugged hills. His game table might look something like this.

| Trail continues generally in same direction | 20% |

| Trail bends gently to the right | 20% |

| Trail bends gently to the left | 20% |

| Trail bends toward the north | 40% |

Our solo gamer needs a technique to generate terrain as his forward elements discover it. He does this by compiling a list of possible terrain and then assigning a probability that this type of terrain will be encountered. It is likely that the trails will avoid rugged hills but they may pass over low rises. A way of doing this is to generate terrain as the forward element moves 2 inches past a piece of terrain or every 6 inches of relatively flat terrain. Examine the charts below.

Thus, if we have a force following the trail, we generate the trail every time the'~point man'' gets within an inch of the end of the trail as we know it. We generate six inches of trail at a time, perhaps laying down a piece of string as we go to mark it. The table is constructed so that the trail generally moves northward. The soloist needs to use common sense here. If the trail is in danger of exiting the table he may want to eliminate the choices that would result in that event. As a trail approaches within six inches of the known trail atop the ridge he may want to forgo a die roll and just connect the pieces. It is entirely possible that the two trails intersect in which case they should probably cross one another rather than merge into one.

Now for terrain. As the lead elements passes an inch beyond a known piece of terrain, he rolls see what terrain is ahead. As he generates terrain, he places it two inches beyond the "point.-'

| flat land | 40% |

| low rise | 30% |

| rugged hill | 30% |

Of course, in another situation there would be any number of terrain features such as Farmer' s fields and barns, stone walls, marshes/swamps, clearings, orchards, woods, streams, etc. The soloist has to exercise some judgment in locating the terrain features in relation to the trail if he is on a trail. If he rolls rugged hill, it should be placed on either side of the trail. When this is the case, roll again to see which side of the trail and roll once again to see what terrain appears on the opposite side of the trail. It is best to lay the terrain down and adjust the trail to the terrain. Continue to roll for terrain when you approach the sides of the ridge except that flat is not a possibility. And once on the ridge top, the terrain is flat. Okay, we have a technique for generating terrain as we go. Now let's look at coming up with some interesting enemy activity.

The Enemy

There are a number of types of enemy situations and permutations based on whether the situations include obstacles of some kind. For simplicity sake, the possibilities we will use are these:- roving patrol

- ambush

- artillery strike

- concrete pill box

Because the programmed defender probably has some manner of security zone in front of his main defensive belt, we will want to devise a system to replicate this. Thus, we place a line east west across the game table, dividing it into two areas. The line can be a piece of string or marked by similarly colored pebbles. The defender's security zone is south of the line while his main line of defense is north of the line. Thus the odds of running into a patrol are higher in the security zone while pill boxes are non-existent there. Now, establish a mechanism to determine when a force encounters enemy activity. For example, roll each turn for each separate force working its way through the Siegfried Line. Perhaps the odds are one in four each turn south of the line of an enemy encounter but one in three north of it. If a force encounters the enemy, roll a percentage die to see what type of incident it has stumbled into.

| Security Zone | Main Defensive Belts | Type of enemy activity |

| 1-30 | concrete pill box | |

| 1-50 | 31-60 | roving patrol |

| 51-80 | 61-90 | squad-sized ambush |

| 81-00 | 91-00 | mortar/artillery strike |

You can devise further tables which give some variety explain further each type of incident. For example, if the Americans encounter a concrete pill box, you roll a I D6 to further describe what that force is up against.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| reinforced by barbed wire obstacle | x | . | x | x | . | x |

| reinforced by small minefield | . | x | . | . | x | . |

| scattered anti-personnel mines around the pill box | . | . | x | . | . | . |

| log bunker with LMB within supporting range | . | x | . | x | . | x |

| registered artillery target in kill zone | x | . | x | . | x | x |

For example, if you roll a four, the approach you find yourselt'on is under fire from both a concrete pill box and a log bunker (i.e. fire simultaneously from two directions) and there is a wire fence keeping you from immediately escaping the opening fusilade.

There is the issue of the orientation of the fire emanating from the pill box or log bunker. You will not necessarily encounter each enemy position from the direction most advantageous to the German player although that will often be the case. In fact, as a tactic you will want to pierce the main defensive belt and then hook around so as to approach other positions from the side or rear if possible. From your research you note that typical pill boxes have a primary direction of orientation from which the major weapons system can fire (in this case a heavy machine gun perhaps) as well as firing ports for small amis. Likewise, the log bunkers probably are ambled with a single light machine gun and can bring small amis fire in two other directions. Both pill boxes and bunkers have some dead space into which they can not fire but the two of them together are oriented so that each covers some of the dead space of the other. The solo gamer uses common sense in setting up the enemy defenses as he encounters them. The positions are placed on the wargame table so that the prime direction of fire falls along the most obvious direction of approach. This may be along the line of the trail or along the flat corridor between hills. Likewise, wire obstacles and minefields are laid out most advantageous to the enemy and scattered anti-personnel mines are found along less likely avenues of approach to the position.

Earlier I mentioned that the enemy has counterattacks planned to eject us from his defensive line. We want a mechanism to determine whether there will be a counterattack and when it will strike. For example, the table below depicts using a I D6 roll starting at the 3r~ turn aRer running into a pill box. The x represents an enemy counterattack. If no counterattack results from the roll in turn 3, roll again in turn 4 with increased odds that a counterattack will happen. However, if no counterattack is launched by turn 6, then the Gemman "player" will not launch one for that particular encounter. Likewise, the American player can devise a table which describes the strength, equipment, and levels of morale, training, and leadership of the counterattack force.

| die roll | 3rd turn | 4th turn | 5th turn | 6th turn |

| 1 | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | - | x | x | x |

| 3 | - | - | x | x |

| 4 | - | - | - | x |

| 5 | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | - | - | - | - |

The Fight

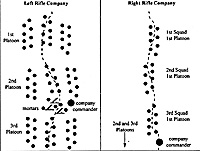

With rules in place, the solo player devises his plan. For purposes of illustration, he sends one company down each trail and maintains the third in reserve. He divides special weapons (flame throwers, heavy machine guns) between the two forward companies. He attaches his mortars to the company on the left trail and gives priority of artillery fire to the company on the right.He arrays the left company with platoons in column. The interval between platoons is such that the fire directed at the iced platoon will not pin down the platoons to its rear. Thus the platoons are out of visual contact. The solo player gives the following platoons instructions to cover when they hear the lead platoon encountering the enemy. Typically this might be to halt until a runner frown the lead platoon arrives with enough information for the following platoon to react.

The squads are on line with the middle squad on the trail and the others two inches away. Thus the left company will move at the speed of the squads moving cross-country. However, when the enemy is encountered, at least two of the three squads should be able to react immediately. The right company moves with platoons and squads in column and on the trail, at least initially. This gives speed until opposition is met at which time the trailing squads will move up along the left and right respectively trying to find a vulnerable flank. The two formations look like this.

Larger version - very slow (31K)

Once the solo gamer has chosen formations and issued orders, he starts off both forward companies and lets the dice generate terrain and enemy activity as he moves forward. The intellectual challenge of command will be to choose appropriate tactics, to figure out when to replace a depleted lead platoon with a fresh unit, and when and where to commit the reserve. Each game should unfold differently and present a variety of challenges to our solo gamer. Next issue, 18th and 19th century fighting in the forests of North America.

Back to MWAN #86 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com