Our hapless Private Smedlap stepped on an anti-personnel mine and became "metabolically challenged" to the use politically correct termino]ogy. Fortunately, he is plastic and paint and will have many more adventures in the future. Smedlap met his fate in a solo skirmish and his demise prompted me to get my thoughts together on obstacles in general and how to apply them to wargaming. Smedlap wasn't the only motivation.

I just completed writing a piece on the siege of Fort Erie in 1814 and I had been struck by the pivotal role of a well-placed abatis, but more on that later. For what they are worth, here are some thoughts on the use and value of obstacles in wargaming.

Obstacles are used to produce three effects: to get the enemy to go where you want him to go, to keep him away from where you don't want him to go, and lastly to hold him in a place where you can deal with him. An ancillary effect is to inflict casualties by the obstacle itself.

The great corollary of obstacles is to always cover an obstacle with observation and fire. Obstacles are generally more useful in defensive scenarios but modern methods of mine dispersal are making them useful in offensive operations also.

Let's look at a typical defensive scenario. The defender is numerically weaker than the attacker. If not, he'd probably be attacking. The defender is also spread thinner since there are a number of ways the attacker can go to reach his goal. The attacker, since he can choose the point of attack, can often concentrate overwhelming force on a narrow front. His hope is to make a penetration quickly enough to get through the defensive line before the defender can effectively counterattack. The defender, then, looks to obstacles for assistance.

Of course, obstacle building is labor and material intensive so effort spent on obstacles is effort taken away from building defensive positions. You may want to figure this trade off into your rules. Perhaps the defender has a number of preparation credits with which he can buy his choice of defensive positions (yards of trench line, numbers of bunkers) or obstacles (yards of barbed wire, square yards of anti-tank minefield).

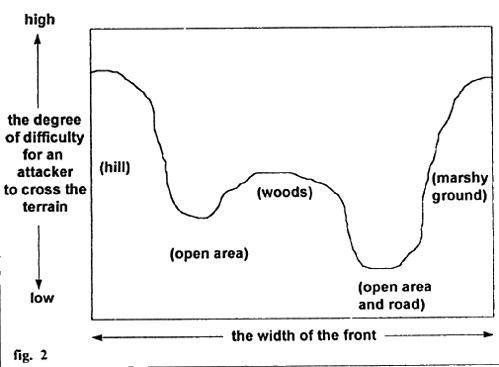

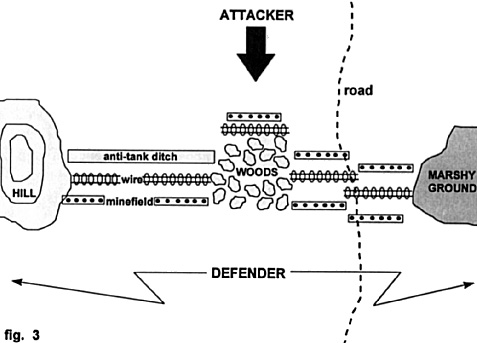

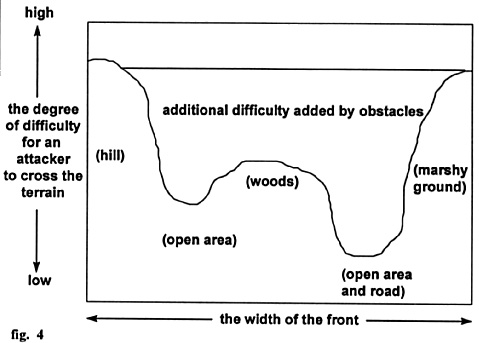

The defender will want to be economical in his use of obstacles, which are a limited resource. Therefore he will want to come up with a plan that integrates the obstacles into his defensive scheme. A novice will typically spread his obstacles across the front in those areas which are easy going for the enemy in order to slow him down a bit. This is a dangerous methodology. The figures below illustrate the point.

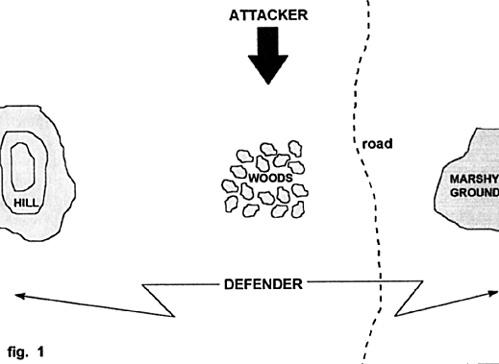

Figure 1 shows a scenario in which a defender has the mission to stop an armor-heavy attacker from penetrating the lines and exiting the table.

What this means is that from the attacker' s point of view, any axis of attack is equally difficult and therefore it doesn't matter which way he goes. Before he emplaced the obstacles, the defender might have surmised that the attacker would send the main attack along either of the two open areas. However this is no longer the case. Thus the defender has to be ready to stop the attacker across the entire front. His job is now more difficult for although the attacker will move slower, the route he will take can only be guessed at.

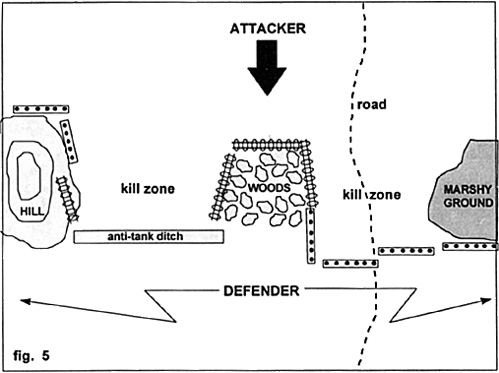

Let's look at another solution. The defender analyzes the terrain, this time looking for places where it will be easier to destroy the enemy. Let's call these kill zones for sake of discussion. He also looks for places where it will be difficult to kill the enemy. His method is to emplace obstacles which will guide the enemy away from areas where it will be hard to destroy him and into kill zones. He builds obstacles to hold the enemy in the kill zones so he can fire on them longer. He then places his troops in positions where their fire can reach effectively into the kill zone.

His key positions, perhaps ones which can fire into more than one kill zone or ones which block an avenue of approach, are themselves protected by obstacles. When possible, he ties man-made obstacles into natural obstacles in order to extend the value of both. Figure 5 is a possible solution which speaks to these methods.

The defender places his armor-killing weapons on the hill or in the woods. He might also place them behind the crest of the hill or behind the woods, where the attacker could not engage them until he was deep in the kill zone. The obstacles protecting the hill and woods might be visible, thus persuading the attacker to steer clear. However, the obstacles at the far end of the kill zones - the obstacles intended to hold the attacker in place - these would be camouflaged or otherwise hidden. Thus the attacker can be coaxed into taking what appears to be the easy route through the defenses.

Do we hide the obstacles or do we leave them open to detection? A hidden obstacle surprises the attacker and perhaps catches him so far committed into an avenue that he can not easily back track to find another route. Hidden obstacles, such as a field of buried mines, may take longer to emplace but are otherwise well suited to holding an enemy in a kill zone. Obstacles in plain sight, such as wire, anti-tank ditches, abatis, and surface-laid mines, are more useful in guiding an enemy away from the obstacle and toward the kill zones. The enemy commander sees the obstacles in his way and steers a new path to avoid them.

Obstacle Theory at Fort Erie (1814)

Back to MWAN #85 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1997 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com