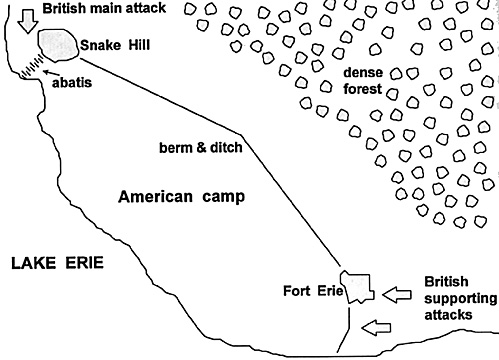

Which brings me to the story of the siege of Fort Erie (1814). The British force under Lieutenant General Sir Gordon Drummond had laid siege to a smaller force of Americans under Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines. Fort Erie was along the shoreline where Lake Erie flows into the Niagara River. The American force was much too large to fit into the small fort and therefore the Americans surrounded their encampment with a ditch backed up by a berm of dirt.

The ditch was between four and five feet deep and the berm was four to six feet high. This was judged surmountable by determined infantry so the American engineers directed work parties to place abatis in the bottom of the ditch and in the sides of the berm. The abatis was a tangle of interlocking tree limbs and branches whose tips had been sharpened and pointed toward the enemy. Those diabolical Americans also weaved thorn vines throughout the abatis for added effect.

Fort Erie was at one end of the camp while the other was guarded by a low mound of sand known locally as Snake Hill. Snake Hill was about forty yards or so from the shoreline. The defenders built gun positions atop Snake Hill and the fortification was named Towson's Battery after the artillery commander there. Eventually the Americans built a low abatis between the hill and the lake to close the gap.

General Drummond was at the far end of a shaky logistical line and he was persuaded to end the siege quickly. His scouts could not approach the fort too closely because of the open area between the encampment and the dense forest further inland. Nonetheless, his scouts, the skillful natives from the Grand River Indian settlement under their leader, the hard-fighting John Norton, kept the fort under nearly constant surveillance. They did not, however, discover the abatis between Snake Hill and the lake waters.

Drummond's plan was to send the main attack after midnight directly between the lake and Towson's battery. To maintain surprise, he had the attack column remove the flints from their muskets so that none could be accidentally discharged. This would be a bayonet assault against what he hoped would be an American army caught sleeping. He planned two supporting attacks on the opposite side of the encampment - one directed against the wall between Fort Erie and the lake and the other directly against the fort itself. These attacks, timed to occur shortly after gunfire signaled that the Americans were responding to the main attack, would tie down the Americans and keep them from reacting to the real danger.

Night Attack

Little goes right in a night attack. The British main attack column moved through the forest undetected and without getting lost but as they approached the fort they alerted the picket guard who fired warning shots before fleeing. The British were right on their heels as the picket came through a narrow gap between the abatis and Towson's battery. It was reported that the last American was stuck by a British bayonet just as he reached safety.

But as the British rounded the corner of Snake Hill, they ran directly into the abatis. What was worse for them, the sentry's warning provided enough time to the local commander to react. He positioned two companies of American infantry in line behind the abatis who opened fire at the halted cluster beyond. These musket-firing iniantry were joined by the guns of Towson's battery firing as fast as they could at the milling mass below.

The British at the rear of the colurnn, unaware of the problem, pushed against the troops to their front who, without flints, could not return fire and cou]d find no way through the abatis. Some intrepid attackers waded into the water to go around the obstacle but were captured when they returned to shore. Unable to go forward, men falling at every American volley, officers losing control of their soldiers in the dark, the British fell back into the forest. Drummond, who was with the other two columns, could not know his main attack had failed when he sent in the secondary effort. The two columns careened forward, out of the woodline and across the open area directly in front of the American camp.

The Americans opened a deadly fire which stopped one column cold. The other gained a toehold in a bastion of Fort Erie and slowly pushed the Americans out. The fire fight and bayonet assaults raged back and forth. The British unable to penetrate deeper into the fort and the Americans unable to recapture the bastion. This situation persisted for nearly an hour when a most unexpected event took place! But I digress.

The point of the above tale was to illustrate the value of even small obstacles at important places which remain undetected. Had the British scouts detected the abatis, perhaps Drummond would have planned his attack differently. Had the American sentries not been alert, maybe those two companies behind the abatis might not have arrived in time to stop the determined assault.

Had Drummond not ordered his men to remove their flints, the British might have forced the defenders back from the abatis by musket fire. With the failure of the night assault, the siege dragged on for several weeks. Finally, American Major General Jacob Brown led a sortie out of Fort Erie to attack the British siege batteries in the forest. This time, the Americans ran into British abatis which took its toll. But that is another story.

In summary, remember that obstacles are used to produce three effects: to get the enemy to go where you want him to go, to keep him away from where you don't want him to go, and lastly to hold him in a place where you can deal with him. A lesser effect is to inflict casualties by the obstacle itself. Finally, the great corollary rule is always to cover an obstacle with observation and fire.

Back to MWAN #85 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1997 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com