The large, floppy hat seemed more appropriate headgear for a farmer than for a Roman General, but Sulla did not mind the contrast. Indeed, he even went so far as to deny himself the traditional mount - opting instead for a sturdy mule. Today howeuer, the mule was back in camp. Sulla had aduanced on foot with his army. And on deployment for battle, he stationed himself - some thought uncharacteristically - with the rescue legion. But those few did not know Sulla, did not know that he did euerything with a purpose. On this fine fall morning, Sulla's purpose was singular: he wanted to destroy the Pontic host arrayed on the grassy plain before him.

INTRODUCTION

This wargame report marks the final installment in the series of battles fought with the ARMATI Rules and documented for the readers of MWAN. Instead of being another exploration of different periods and forces, this particular wargame returns to the initial conflict, once more pitting the forces of Pontus against Rome.

Readers may recall that the first battle resulted in a victory for Rome. The idea for this second battle was born from that engagement. The historical "twist" in the rematch being: both Sulla and King Mithridates were on the field, the Pontic force included a large contingent of Galatians, and the Romans were not fighting from behind the ramparts of a camp.

Like the previous wargames fought under these rules, this engagement was also conducted with cardboard counters representing 15mm epic-scale armies. Unlike the previous wargames however, this battle was fought with forces three-times the size allowed under the ARMATI Rules. And against the advice of the rules system author, I elected to design a scenario where a Roman Army would be challenged by a combined host. In order to accommodate the amount of units on the field, the table size was increased by one and one-half. The basic 64 x 32 inch table top, was extended to 96 x 48.

Terrain was waived for this battle, even though all combatants are allowed rolls per the army lists. It was assumed that the King had chosen ground suitable for his cavalry and chariot arms, so hills and wooded areas were absent. As the forces in play were three times the size of a "normal" force, the number of divisions allowed and number of key units were increased by a factor of three as well. The question of command was solved by borrowing a little from the DBM booklet. That is to say, each Roman Legion was commanded by a general. Lucius Cornelius Sulla was the overall commander on the field.

Reflecting the generally inadequate command of the Pontic host, the Galatians had their chief, while the Pontic force had one general (more capable in military matters) in addition to the King Each general/commander was given a rating for ability that could benefit or detract from a unit's performance.

(The ARMATI Rules allow a +1 modifier for units in melee with a general attached. For this game, the rule was adapted slightly: Sulla provided a +3 modifier to any unit he was attached to in combat, while Kzng Mithridates provided a -1 modifier.)

For this final scenario play-test, all basic and advanced game rules were in effect.

DEPLOYMENT

Aa Commander, Sulla had wrestled with the problem of dispositions a full week before the enemy was brought to battle. His was basically an infantry force, facing a mixed-enemy that contained large numbers of cavalry and chariots. The problem was compounded by the fact that the latest reports from Rome showed that things were not going well on the peninsula. Sulla could not risk ending the campaign season without a decisive battle in the East; he could not remain in Galatia any longer than was necessary. In some respects, Time was even a greater threat than any force commanded by Mithridates. Accordingly, Sulla accepted the field of battle as chosen by the Eastern King.

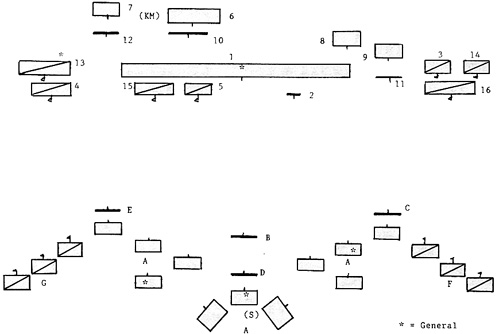

The Pontic host was arrayed in three main lines on the field. The first two lines ran in a north-south direction. The third line ran in a similar direction, but was angled to the right.

Starting on the right flank then, the Pontic General had placed the 2-horse chariots (4). This Galatian unit was supported by a large group on Cataphract Cavalry (13). The Pontic field commander attached himself to this unit of powerful horse. In the center were stationed the scythed-chariots (16, 6), the general hoping against hope that this time, they would have more impact against the Romans. To the immediate left of this formation, the Galatian chieftain had placed his small compliment of javelin men (2). Standing directly behind this light screen, were no less than 9 units of warband infantry (1). The Galatian chieftain was in the front ranks of the center band. About 120 paces to the left of this massive wall of warriors, stood a amall division of bowmen (11). Over on the left flank of the Pontic host, were arrayed four units of light cavalry (16).

The third line began behind these light horsemen, where two divisions of heavy cavalry (14, 3) - one Pontic and one Galatian - waited for the commencement of hostilities. The remainder of this third line angled away to the right rear of the Pontic position. It was like the entire reserve was formed as an echelon of horse and phalanx. Behind the unit of archers and to the left rear of the Galatian main force stood a phalanx of Iberians (9). To their right rear, stood another phalanx. This unit however, was comprised of mercenary Greek Hoplites (8). Located more directly behind the Galatian contingent, but at a good distance, was the main phalanx of the Pontic force. As a screen for this hedge of pike-armed infantry, there was a large division of javelin-armed light infantry (10), roughly 100 paces to its front. Completing the third line, the Pontic General had placed his "imitation legion" (7) well to the rear of the gap between the right and center. Providing a screen for this division was a medium-sized group of skirmishers (12). As for the King, well, not wanting to be confined or even pressed with matters of unit command, he selected a spot in between the main Pontic phalanx and the pseudo-legion (KM).

By this disposition, the Pontic-Galatian army had nine heavy divisions out of an allowed 13 and five light divisions from a possible 14. The break points for each army would not be combined: the Galatians would quit the field with the loss of four key units, while the Pontic force would so the same upon losing nine key units. By tlus disposition too, King Mithridates hoped to overwhelm the legions deployed to his front. The key points in this simple battle plan were the success of the cavalry wings and the attack of the Galatian warbands. There objective was, in the words of the King, "to tire and weaken the Romans, making it easier for my troops."

Against this impressive spectacle, Sulla deployed his legions and auxilliary troops in three large wedges. Two of these wedges combined to make up the first line of defense. One legion was held in central reserve, deployed in a tighter wedge formation, as the flanks of the inverted V were comprised of legionnaires deployed in depth.

On the Roman left flank, three units of Germanic cavalry were placed (G). At the point of the left wedge, a small unit of archers stood (E). They provided a covering force for the first division of cohorts (A). The rest of the legion on this side of the battle-line deployed on an angle toward the center of the position. The General of this legion attached himself to the middle division of cohorts, who comprised the supporting line. The right wedge was deployed in a similar fashion. The exceptions being: the covering skirmishers at the point of the right wedge were slingers (C), and the cavalry force on the flank was made up of Spanish heavy cavalry (F).

In the center of the Roman position, a substantial gap had been left. Forward of the main battle lines, this gap was covered by three units of light infantry (B). To the rear of this gap but in front of the cohorts of the third, reserve legion, stood another three units of javelin-armed skirmishers (D). Sulla (S) took a stand on a small rise of earth that he had ordered prepared for the battle, behind the front line of this legion. The General of this legion, ever mindful of his commander's presence, attached himself to the front-line cohorts.

Out of an allowed 18 heavy divisions, the Romans had deployed 17. Of nine light divisions available, they had placed eight. The Roman disposition was symmetrical and creative, for it provided for defense in depth against the strong cavalry arm of the Pontic host, as well as provided for offense in depth against the average infantry components. Indeed, Sulla's plan of battle was as simple: he hoped for a tie on the flanks - having recognized the seemingly inherent weakness of Roman horse - and would accept nothing less than complete victory in the center. He was confident of his legions, the barbarians would not stand against veteran troops. The only real concern he had, just as with the larger issues awaiting his return to Roma, was again, Time. Victory in the center was required before the Roman horse gave way.

Opening Moves

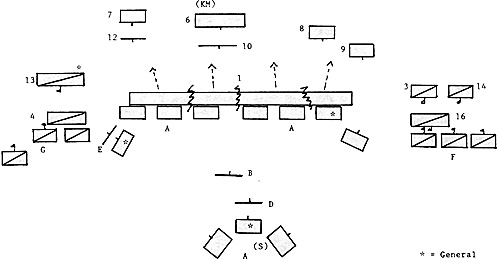

Due to the advantage in Army Initiative Rating, the Romans dominated the first three turns of game. With each win of the move sequence however, the Romans deferred to the Pontic host. As their deployment and plan dictated, the Pontic force began the engagement with a general advance toward the waiting lines of metal and grey.

In the front, rather ineffectively as it would turn out, were the chariot and Fight cavalry elements. To be sure, each rank advance was followed by the heavy cavalry and cataphracts, but at a distance due to different movement rates and the overall plan of attack. In the center, the Galatian warbands advanced in a veritable wave of screaming, sword-brandishing warriors. King Mithridates held his own infantry back for two turns of movement in order to establish a safe cushion between the barbarians and his own phalanx units.

The first firing took place on Turn 3, as the Romans loosed arrows and javelins into the advancing scythed-chariot groups. As in the first meeting between these enemies, the chariots were soon riderless and/or horseless. On the Pontic left flank the light cavalry did score a single BP against one of the units of Spanish heavy cavalry. In the movement phase of this same turn, the Romans sprung to life. On the left flank, the Germanic horse (G) charged out into the midst of the two-horse chariots, and an exchange of BPs resulted. The third unit of Germans stayed back to see what the Cataphracts would do in response.

In the center, the legions began to straighten their front line units while the supporting cohorts turned to each flank in order to face the assumed threat of cavalry attack. The remaining unit of scythedchariots (16) threw itself into one of the waiting cohorts. After a sharp struggle, the Romans destroyed the desperate Pontic charioteers. Over on the Roman right, the Spanish cavalry had attempted to reach the bow-shooting lights to their immediate front. Due to the nature of their deployment, only two units of the three could "come to grips". The light cavalry (18) obliged the challenge to combat and were subsequently rolled over by the heavier Spanish (F). One unit was broken while another two were reduced to half-strength. The Spanish, save for the initial loss from bow fire, took no casualties in the one- sided melee.

A WALL OF WARBANDS

Action on the flanks would continue throughout the game, but at this point, the beginning of Turn 4, the center was the focus of attention for both Sulla and Mithridates. The Romans had pushed their cohorts into a single straight line across the center of the field. It was a dotted-line however, as the units were separated by some distance. On each end of the line, auxiliary units faced inward slightly in order to bring the wall of Galatian warrior under missile fire. In the center of the Roman line, the light infantry readied another volley of javelins.

As the Galatian continued their advance, missile fire was exchanged between the skirmishers (2) screening the warbands, the Roman slingers (C) on the right, and the Pontic archers (11) - stationed on the left of the long line. While the slingers did score a hit on the archers, the Galatian javelin men scored two hits on the waiting line of legionnaires. The volley by the light infantry covering the gap (B), made no dent in the wall. Movement for this phase saw the light infantry turn and retreat through the gap. On the Roman right, the advance of the legions dispersed the irritating skirmishers, but did not establish contact with the screaming warriors. Accepting this misjudgment of distance, the Roman infantry calmly ordered their ranks and prepared to launch a shower of pile into the inevitable rush.

Sure enough, a sudden movement in the center brought the entire line of warbands across the remaining distance, and crashing into the Roman line. Pila, scutum, and gladius did quick work however, as each cohort survived the impetus of the attack, and inflicted a BP loss against each warband - save for that one band in the center commanded by the chieftain. This melee would last for several turns; each turn adding to the pile of Galatian dead in front of the cohort line. Indeed, with unremarkable loss, the Romans had quickly reduced to the wave of Galatians to a ripple upon the now blood-soaked plain. Each general survived through the melee turns - the Roman commander on the right and the Galatian chief in the center. Even though &tigued, the Romans still held an advantage.

(The advanced rule section of ARMATI provides that units engaged in melee for a number of turns equal to their original BP strength become exhausted. If still engaged in the following turn, the unit suffers a negative modifier to the melee roll.)

In desperation the Galatians threw their last into the melee. It was to no avail. One by one, the warbands broke on the Roman line. In the space of a single turn, four units ran, and the Galatian general's luck finally ran out: while his warband lost only one BP in the long fight, he was cut down attempting to stop the rout to his immediate right.

ROMAN CAVALRY, TYPICALLY

Compared to the long struggle in the center, the Roman cavalry contingents enjoyed quick success on the flanks. This success was to be short-lived however.

On the Roman left, the combat against the Galatian two-horse chariots (4) lasted for a couple of turns before the Germans broke through. Unfortunately, the large wing of Pontic cataphract horse was waiting for the resolution of the melee. The two units of allied horse, also tired and at reduced strength, charged off into the ranks of these very heavy horse. The third unit, not yet engaged, also joined the fray.

The Germans sold themselves dearly against the leveled lances of these cataphracts (G v. 13). The one unit of Germanic cavalry that had suffered no loss was destroyed by the counter-charging Pontic force. The other two units were not broken, but each did suffer a single BP loss in the ensuing melee. In the meantime, the unengaged cohorts of the second rank and of the third reserve legion dressed their ranks and prepared to meet an inevitable advance. The next turn saw the weight of the cataphracts tell, for the remaining Germans were completely dispersed.

Over on the Roman right, things went a little better in that the Spanish allied horse lasted a little longer than the Germans. In another turn, the light cavalry (16) interfering with the advance were overwhelmed. The one Spanish unit that had broken its opponent used a breakthrough move to advance upon the waiting lines of Pontic and Galatian heavy cavalry. Charge begat charge on this flank, as the blood-crazed Spariiards broke a unit of Galatian horse. In their disorganized state however, they did take a single BP casualty from the other Galatian unit (F v. 3). To the right of this engagement, another rolling melee developed as the Pontic horse advanced against the reduced Spanish (F v. 14).

In subsequent turns, the Galatians gave as good as they received, eventually forci the retreat of the Spanish horse. The Pontic heavy cavalry fared much better, and easily dispatched the remaining squadrons of Spanish.

And so, by the end of Turn 8, the Romans were still licking their wounds and reorganizing ranks in the center. They could not be so concerned with the flanks, as that had been left to the supporting line of cohorts and the reserve legion under the direct supervision of Sulla. Besides, while the front lines had been cleared of Galatians, several large phalanxes of Pontic and Allied foot were advancing upon the Roman line (9, 8, 7, and 6). It was all a poor legionnaire could do to adjust his chin strap, shield, and look for another pilum with which he might face this second attack. At least the advancing hoplites and pikemen would find the footing difficult, for the blood and bodies of some 7,000 Galatian warriors littered the ground in front of the Roman line.

CATAPHRACT CATASTROPHE

As the ranks of Romans in the center and on the right of the front line were being harassed by fresh light infantry (10), the Pontic field general split his wing of cataphract horse. Two units were directed against the second Ime of cohorts commanded by the legion general - and the other two units were sent deeper into the Roman left flank.

(Under the ARMATI rules, a general may voluntarily split divisions of units. That is to say, the original deployment may be slightly modified by the progress of a battle or by the change in plans. However, by so splitting up the divisions, the army initiative rating is reduced by a factor of two. To quote directly from the rules, whether the split is by command or by the result of combat, "A divisional split represents a disruption in the command structure.")

By chance or design, a similar development took place on the Roman right. The weakened unit of Galatian horse (3) charge into the second line reserves, while the Pontic horse (14) wheeled slightly and advanced toward the legionnaires of the reserve.

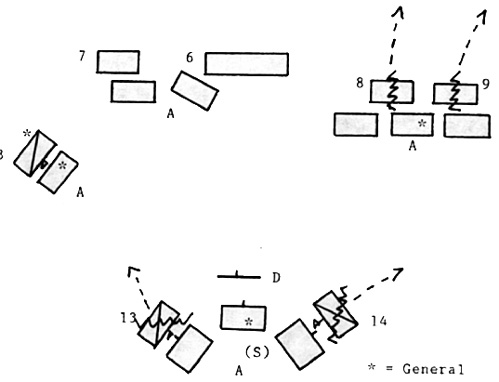

Contact was first made on the shorter flanks, neither infantry or charging horse giving ground. The Galatians were bounced and then broken. On the Roman left, the cataphracts were also bounced by the steady legion infantry: each unit taking a BP loss in the melee. A similar result occurred in the next turn as the heavy horse attempted to regain an impetus. The Romans calmly delivered another volley of pile and then attacked both horse and rider. Both Roman and Pontic general found themselves in the thick of the fighting, but neither suffered fatal i~unry, so surrounded were they by body guards.

Having eliminated the Galatian heavy cavalry, the supporting line of cohorts wheeled back to the front and advanced to the rear of a weak legion line.

Turn 10 witnessed the collision of cavalry into both flanks of the reserve legion. Fortunately, Sulla was present, and the attacked cohorts were deployed in depth. Unfortunately, even this precaution did not save one cohort which broke under the strain of the Pontic charge.

(Under the ARMATI rules, a Hl unit deployed- in depth may not be broken by the impetus of a HC charge. It may however, suffer quite a loss of BPs, making it a likely candidate to rout in the following turn. This is what happened with this particular cohort.)

Having a greater frontage than the Romans, this unit was involved in another melee. This cohort stood its ground, and inflicted loss on the Pontic heavy cavalry. Its sister unit was also roughly handled by the other surviving cohort.

On the Roman left-rear, the cataphracts could not make any impression either. The Romans again, stood firm. One of the cataphract units took two BPs, while the other suffered just one BP. This situation continued over the next two turns. In the end all the cavalry units attacking the reserve legion were routed. The two units of cataphracts that were attacking the reserve cohorts of the first - or left - legion, had been decimated. Only the general of the Pontic force remained, protected a few weak squadrons of horse. To be sure, the Romans lost a few BPs in the process, but these losses were spread among several differed cohorts.

With this defeat of their cavalry arm, the Pontic host had lost a total of five key units. Under the modified scenario rules, the large Pontic force could accept a total of nine key units eliminated before retreating from the field. The Romans, in contrast, could lose 12 key units before breaking off the engagement. In the present turn, their total loss of key units was only three, the two front line cohorts having succumbed to the tough melee with the Galatians and the seemingly endless missile fire from Pontic light infantry, and the single cohort of the reserve legion that routed away when charged by heavy cavalry.

FATIGUE VERSUS PHALANX

While the Pontic cavalry was dying on Roman shields, the center once again, was the focus of attention as King Mithridates had finally ordered his units into combat against the weakened Roman line. Due to the closeness of combatants, the King had decided to attach himself to the pike phalanx.

Contact was made first on the Roman right flank, with the Iberians and Greeks (9 ff) advancing on the much reduced cohorts. In the center, before the advance of the pike phalanx, the light infantry (10) threw themselves against the waiting Roman line. Though normally no match for the armored legionnaire, the light javelin men were able to capitalize on the fact that these Romans were exhausted from the previous combat. In the first turn of this renewed melee, the cohorts lost an additional two BPs. Over on the left flank, the Romans had split one of their cohort groups: one unit overran the skirmishers and fell on the lines of the "imitation" legion (7). The other unit wheeled to the right and charged into the left side of the pike phalanx (A v. ff).

This attack was a surprise to King Mithridates, but he was more surprised to find that his splendid turquoise cuirass and leopard skin cape had been pierced by a stray Roman pilum. He collapsed to his knees, eyes wide as he held onto the shaft that had taken his life. In the front, the legionaries and pikemen exchanged BPs.

(Under the ARMATI rules, if a general is attached to a unit that loses a BP in melee, that general can oecome a casualty on a second roll of '6' on a d(6). The general is also considered a key unit for victory purposes, and so, the Romans, with a single die roll, had increased the Pontic total loss to six key units.)

Back on the right flank of the Roman line, the combat continued for some time. The Roman heavy infantry dispersed their own skirmishers as well as those of the Pontic host when they moved against the Iberian infantry. The Greek phalanx wrecked some initial havoc upon the weak Roman cohorts, but the fact that the general was still there, helped the Romans to hold steady.

Slowly, the tide again turned in the favor of the Romans. The Greek and Iberian allied foot could not make a significant impression upon the Roman line. Unit by unit, their phalanx gave way under Roman pressure. On Turn 14, a unit of hoplites broke for the rear.

CONCLUSION, CRITIQUE. AND COMMENTARY

Sulla's plan of battle had succeeded, but his legions would be in no condition to advance the invasion. Reinforcements would be needed - and immediately. Still, the news that Mithridates had met his end on the field meant that the threat of any further organized resistance would be minimal. The Pontic host had suffered terrific loss to its most valuable arm: the cavalry. The threat of the phalanx against a legion in camp was also minimal, and it was doubted that such action would develop.

The Pontic plan was direct and it did succeed in bleeding the Romans. The use of the Galatian warbands as "cannon fodder", while wise, did not pan out as completely as the King or general would have liked. If only one or two warbands could have broken the line, the outcome of this final engagement might have been different. What was needed was another assault on the Roman line as soon as possible after the defeat of the Galatians.

To that extent, the use of the light infantry (10) was brilliant. The advantage in cavalry was not taken however. The Pontic cataphracts should have concentrated their effort on the main Roman line. The same idea should have been followed on the ooposite flank. If this main line had been involved to the front as well as from the flank and rear, it would have eventually come apart. The reserve legion - Sulla possessing a great degree of common sense - would have retreated in the face of such numbers.

To reiterate my previous assessment: I think the ARMATI rules system works well. My thanks to Mr Conliffe for providing some fun on past evenings and afternoons. These rules are clear, simple, and provide for an enjoyable, realistic (my subjective opinion) game. To be certain, some sections of the rules - like those covering the control of divisions - are a little more complicated than others, but they do lend themselves to the overall feel of the game.

If I may further impose upon the reader, I would like to take a few paragraphs and explore some ideas for rule revisions that stemmed from this most recent game. To be certain, there is the suggestion of basic rule modification allowed under the Scenarios section of the rules system. What I propose are modifications to the basic rules themselves - applicable to the simple "one-off" engagement, as well as to more detailed scenarios or even campaign battles.

- 1. lf command is to play such an important role in these rules - reference

the disruption of command caused by the splitting of divisions - then more of a

penalty needs to be assessed upon the demise of an army general. The following modifications are suggested to the rules covering the use of generals:

- A.Generals should be vulnerable to missile attacks as well as to melee combat. Because of their small number and mobility however, any general and bodyguard should be given a decent missile protection modifier. Of course, this would not apply to those commands on foot.

B.Upon the loss of a general, the Army [nitiative Rating should drop to 0 (zero). This, to reflect the lack of control and complete disruption of command brought about by the loss.

C. Further, on the loss of an army general, the player should roll a d(6) to determine if the army begins to withdraw. On a roll of one or two, the army will break contact and withdraw off the field. This roll will be made each new turn, before the roll for movement order.

2. If a unit with impetus breaks an enemy unit, and is engaged with others due to alignment or overlap, the charging unit should also be able to break facing enemy units. At the least, any unit next to a unit that breaks should be required to take some type of morale check or suffer a negative modifier on the melee roll. (This idea, a result from the Spanish charge into the Galatian horse and from the Pontic horse charging into the Roman infantry.)

3. Movement, specifically the mechanics of wheeling, can be a spoiling factor in the execution of moves that may win the battle. In this particular case, if the Pontic horse could have wheeled and then assaulted the flank and rear of the Roman first line, the outcome may have well been different. In this respect then, there needs to be some sort of allowance for a unit to use only part of its movement allowance, or to have the cavalry more maneuverable than the infantry.

In a final note, I should like to express my gratitude to the Editor of MWAN for publishing these wargame reports. I would also like to thank the readership of this excellent newsletter for their time spent reading my efforts, and comments forwarded on the same.

Back to Table of Contents -- MWAN 84

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Hal Thinglum.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com