This is an attempt to solidify some thoughts on how command and control should be represented in a wargame through the movement. sequencing, and other mechanics of the game. Structure is lacking and coherence will probably be minimal.

Tactical concept is largely centered around the phrase "fire and movement." If we take "fire" in a generic sense that includes all forms of combat we can then say that the two factors that we must model are "fire" and "movement."

As an aside, we can also say that if we consider the wars from the horse and musket period on, it did not take long for the generic fire to become the literal fire. l think we would be safe in stating that from about 1642 the proportion of combat time that was involved in firing was significantly, if not overwhelmingly, larger than that occupied by hand-to-hand combat.

Fire and movement are not independent elements, but are closely intertwined with each other. Furthermore they are both influenced by (perhaps we should say driven by) "command." What is this ethereal commodity called command?

I suppose that if we could really answer that we would be teaching at the Command and Staff College. I don't think that it is possible to answer this directly; however, we may be able to describe some of its effects or characteristics.

- Few good things happen without it.

Good things don't necessarily happen even with it.

Bad things happen in spite of it.

Good units do more with the same amount of command than bad units.

A little command can go a long way if you have a lot of units doing exactly the same thing at the same time in in the same place.

A lot of command can be burned up by even a few units doing different things at the same time and in different places.

Standing still, particularly in combat, can use as much command as moving around.

Moving through rough terrain will use more command than moving through open terrain.

Command is not infinite, it runs out.

Command can to some extent be stockpiled, but only in relationship to one mission.

Change the mission and the stockpile is zeroed out.

Commanders can not continuously replenish the formations' need for command, commanders also run down.

The amount of command available is a function of the commander, the staff, and the situation.

Combat eats command rapidly.

Units fight better and stay longer with command.

The effects of command are pretty much universal across time.

As we have frequently stated, the way in which the typical wargame models time is very "un-real." Unfortunately the tabletop medium we use to construct our models sets many limits.

Real world movement was not arbitrarily cut into a number of bit-sized chunks. It flowed, perhaps jerkily but nonetheless flowed, from start to finish. While the start may have been controllable, the finish was not always so agreeably predictable. The finish of this movement was usually closely tied to command - either the presence or the lack of it. Likewise the amount of time that was consumed by said movement was not necessarily important or relevant to anything.

This unimportance of time is important because time is perhaps the hardest thing there is to model in a wargame. I would go so far as to say it is impossible to model. This leads first to the interesting question of "If it's impossible to model and it doesn't mean anything, why bother?" This leads directly to the answer of "Ain't no good reason." But if we don't model time, what do we do? According to Uncle Duke's Pivotal Insight Number I, you model sequence. Time is only noticeable through the occurrence of events. If you get the event described correctly and you get them arranged in the correct order, does time matter? To attempt to answer this, let's look at an example:

Scenario 1.

Scenario 1.

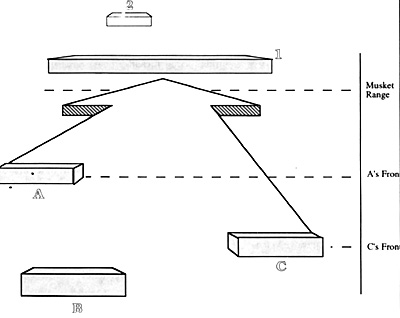

*Forces A and C are going to launch a coordinated attack on Force 1. Let's assume that everyone can see everyone. Commander I is going to want to call in Force 2 as support, but when is he going to give the order?

*Is it when Force C starts to move? Would he know it was going to be an attack? Maybe C is just moving up to come into line with Force A.

*Would Commander I order up 2 when A started moving? Both forces would be advancing, yet maybe they just want to get closer.

*Would Commander I send the order when A and C reached musket range? By this time the situation is fairly clear, yet it may be the start of a fire fight not an all out assault. What will he do?

Before jumping into speculation, lets make a slight change in the scenario for comparative purposes:

Scenario 2.

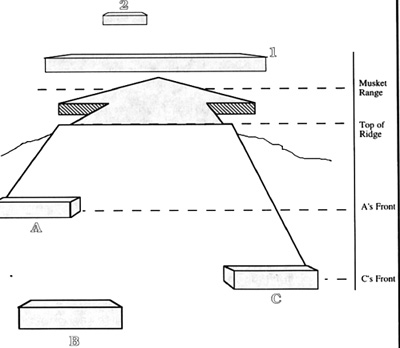

Basically the same situation but now we have a ridge in the way, which Commander I has not posted with pickets making him serenely oblivious to the approaching threat.

Asking the same questions, we know that Commander I will definitely not react to Force C starting to move or Force A starting to move when C comes into line. This leaves the new event when A and C crest the ridge and when they enter musket range. But this still does not answer the question as to when Commander I will give order.

The reason this question is not answered is because none of the factors described does anything to trigger the order. Commander I will issue the order when he decides to issue the order. This could be at any of the possible points described above. (Obviously, Commander I could make up his mind anywhere along the route of advance. I picked what I believe to be the most logical spots based on their reflection of a change in the situation. If Commander I does not issue the order when C first starts moving, I would think that indicates he has decided to wait and let the situation develop. The next development is that C comes up to A's position and they both start to advance, etc. These points become the critical events of the process that A and C are generating by their advance.)

What causes Commander I to make up his mind? First, he wants to be sure that there is an all out attack under way. Committing the reserves on a feint or a probing attack could be costly in the long term. This is a "professional skills" type of assessments commander decision. Secondly, Commander I wants to leave enough time (there's that word) for Force 2 to get into position to provide effective support. What determines this? It's Commander I's evaluation of how long it will take to get the message to Force 2 and how long it will take Force 2 to come up once it has gotten the message; as compared to how long it will take Forces A and C to hit him- another commander decision. If he thinks that Force 2 is really going to hustle, Commander I can

delay having to make the decision to call for help. This increases his chances of correctly assessing A and C's intentions. On the other hand, if Commander I thinks Force 2 will not respond quickly, he will have to make his decision further in advance to allow 2 enough time to respond. This reduces his chances of correctly determining what A and C are up to before he has to make up his mind.

What causes Commander I to make up his mind? First, he wants to be sure that there is an all out attack under way. Committing the reserves on a feint or a probing attack could be costly in the long term. This is a "professional skills" type of assessments commander decision. Secondly, Commander I wants to leave enough time (there's that word) for Force 2 to get into position to provide effective support. What determines this? It's Commander I's evaluation of how long it will take to get the message to Force 2 and how long it will take Force 2 to come up once it has gotten the message; as compared to how long it will take Forces A and C to hit him- another commander decision. If he thinks that Force 2 is really going to hustle, Commander I can

delay having to make the decision to call for help. This increases his chances of correctly assessing A and C's intentions. On the other hand, if Commander I thinks Force 2 will not respond quickly, he will have to make his decision further in advance to allow 2 enough time to respond. This reduces his chances of correctly determining what A and C are up to before he has to make up his mind.

Notice that although we have used "time" a great deal in describing the second factor that determines when Commander I will make up his mind, time in a literal sense does not matter to us. In an abstract sense, what Commander I is really determining is where in the sequence of events being generated by A and C must he issue an order (a new event) to ensure Force 2's arrival (another future event)? Whether the time involved is minutes, hours, or weeks is really not relevant to the outside observer. It's the sequence that counts. "Time" is a common way of discussing or categorizing sequence. And while a real Commander I might think in terms of minutes and hours, for those of us who are modeling the process it is an extraneous detail.

Following along this concept and going back to our two scenarios, what can we learn from comparing them? The big difference, the only difference, between the two scenarios is of course observation. What changes when the ridge is added? For lack of a better term, we can say that Commander I's window of opportunity has decreased. Without the ridge he had a chain of three events with which to deal; with the ridge he has but two. We might say that the physical closeness of A and C when they first appear on the ridge reduces the time in which he has to make a decision. (In this sense, time can be viewed as the distance between events.) But it is only a matter of time, from a gaming perspective, what is different between Scenario 2 and Scenario 1 if we assume that in Scenario I Commander I did not send the order when C started to move or when A started to move? If it is only time, then Commander I should be better off in Scenario 2 than Scenario I because a new event as occurred at the ridge. This is further away than musket range so if he makes the decision at the ridge line there should be a better chance that Force 2 will intercede effectively. In Scenario I he only has the musket range event left at this stage of the advance in which to make his decision.

What of course is different is surprise. If Commander I has been watching A and C advance upon him from the start as in Scenario 1, he will, one would think, be more prepared to make the decision when they reach musket range than he would be if they just pop-up over the ridge. While this is, of course, related to time, it is also strongly related to the commander's abilities. What if in Scenario I he ignores the initial advance or is distracted from it? Will he not still be in a sense surprised when A and C reach musket range? What if he rises to the occasion and immediately grasps the situation and takes all the necessary actions instantly in Scenario 2 when he first sees the enemy on the ridge. Might he not be equally as prepared as in Scenario 1?

And what about the enemy commanders? What if in Scenario 2 they pause at the top of the ridge to admire theview and compose a bulletin proclaiming that victory is theirs? Might they not end up in worse condition than a decisive, non-hesitant advance across open country in Scenario 1?

All of these outcomes are possible, although certainly not equally probably. Furthermore none of them rely on time as the determinant. What they rely on is not the amount of time but the use of time by all the commandersinvolved in the scenario. This is the crucial point and the reason wargames do not realistically and can not absolutely model the passage of time.

Given a specific interval of time, there is an incredibly wide range of things that can be accomplished within its bounds. Within limits, that may be quite broad, the absolute amount of time available may be the least important factor in determining what is in fact achieved. For this reason, I think we can conclude that we mustrely on abstraction to produce, define, and sequence our events. Not only must we rely on abstraction, we can indeed do so with confidence that it will produce events that are at least as historically consistent as any attempt at time modeling

There is one additional insight to be gained here. That is that after the plans are made and the first formations begin their movement, all decisions to do something other than what the plan says are a reaction. They are event driven. They do not spontaneously generate themselves from nothing.

This is not how it happens on the tabletop. While the decision in the gamer's mind to do something is undoubtedly a reaction to an event, its effects in tabletop "reality" frequently can only be explained by spontaneous generation or devine intervention for there is no logical way for it to have happened otherwise. This is the "500 foot tall general" or "heliocopter command" effect that we all know and love.

The problem is that there are no "true" ridges in wargames. We have not been able to consistently and reliable create surprise, or its corollary-ignorance, on the tabletop. This is not really the garners fault (although one mamay make an exception to this in the case of ignorance). There is just no way of keeping secrets from yourself As long as we rely on the gamer to provide the chain of command in his head, we will never solve the problem.

We have tried many mechanics in an attempt to mystify the command environment and in the process to increase the suspense, excitement and challenge for the gamer. But such mechanics as hidden movement, written orders, activation casts and others have not seemed to produce much of an effect beyond complicating the game. The gamer is too biased, to competetive, too all-knowing, too all-powerful to be ignorant and surprised.

If we compare our efforts at building the fog of war into command and control with the morale check, which is a very open mechanic, we may see something quite interesting.

If we consider a unit placed in a gaming situation that results in a morale check, we see that there is nothing hidden from the commanders (gainers) of either side. The break points are known, the situation modifiers are known, the timing of the event is known, even the probably outcome of the check may be known by the gamers. But yet the morale check has the ability to gain the gamer's interest, to capture the gamer's attention, to surprise the gamer, to impact the gamer's actions and thoughts. Why is something that is so visible so successful in generating suspense and gaining the interest of the gamer?

The answer is not as simple as saying that the outcome is unpredictable. Certainly this is the case, but the outcome in a well written game, while unpredictable is not capricious. Many times the outcome can not even be considered unpredictable. With very low and very high break points the outcome is very predictable. It is only in the mid-range that uncertainty asserts itself. With a 50% breakpoint you really don't know what is going to happen. This is certainly a source of suspense; yet the possibility, if not probability, of the less likely event occurring at either extreme point is also a source of anxiety and excitement for the gamer. What a wonderfulmoment when the guard staggers or the landwehr performs heroically.

So if it is not the unpredictability, what then makes the morale test exciting? For one thing, morale tests are perhaps unique in wargaming mechanics in being truely decisive events. With the possible single exception of melee resolutions, no other mechanic consistently produces such definitive and high impact results.

Frequently not even melee resolutions are as decisive. This difference in decisiveness is certainly true when one compares morale tests to virtually any command and control mechanic. The sad truth is that command and control mechanics really play a very limited role in the outcome of the game. And such roles as they do play tend to be subtle rather than dramatic. Let's face it, wargames are combat oriented, not command and control oriented.

Another reason I think that command and control mechanics don't capture the gamer's imagination is that most of these mechanics occur in the gamer's world, not in the game's world. By that I mean they are detached from what is happening on the table. They tend to be structured to form a bridge between the gamer's mind and the tabletop. The major flow of information is in one direction-towards the tabletop.

Very little from the tabletop comes back to impact the gamer in a commmand and control sense. In the morale check everything you need to known is on the table. To wax poetic, it is the unit on the table that is the determiner of its fate. The dice are just its way of communicating with us in the outside world who are observing the event.

This perspective calls into question the role of the gamer in the wargame. This is something that we have never dealt with very well. We have in fact ignored it (or decided not to decide), and as a result, we have made the gamer god by default. This may be another reason that command and control is so boring. What fun is it to be god? Where is the challenge?

To again look at the morale check, while it is true that the gamer may maneuver the unit into the situation that may require the check, at the moment of the check the unit "takes over." Then the gamer is going along for the ride. The gamer becomes the passenger on the roller coaster, not the operator. Excitement, if not panic, enters the game; and it is flowing from the tabletop to the gamer.

What then is the gamer to do? How do we define his role? Is he god, commander, or observer? I would say that by necessity he must be all of these, but that we could improve the challenge for the gamer if we carefully segregate and control when he can play each role.

The gamer can be god when the plan is being made before the game is started. This is a perfectly legitimate time to be god. You can know what there is to know at that moment which can be tightly controlled by the game setup. But, once the game has started, we need to put aside our godhead and not be allowed to again take it up. For the actual playing of the game we must restrict the gamer to being either the commander or the observer-and this must be stringently done.

Since the gamer will be called upon to play all the commanders in his force the task of limiting his perspectives is a challenging one. But if we view the process as a reactive one and not a proactive one we may achieve so measure of success. This again comes with the careful definition and use of events. Only commanders who can see an event can react to it, otherwise they continue to carry out the plan. While in this non-reactive state of plan execution the gamer is the observer, which is not to say he is inactive. As with the morale check he will have to cast and move but it is the tabletop world that is dictating the events to the gamer not the gamer's world to the tabletop.

How would this be accomplished? That is the challenge for designers. More attention is being paid to this facet of game design. The future should be very exciting, and quite a bit more challenging!

Back to Table of Contents -- MWAN 84

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Hal Thinglum.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com