In March 1824 Britain and Burma stumbled into war. a conflict brought about by mutual antagonism, territorial design, and ignorance of two totally alien cultures. The first Anglo-Burmese war of 1824 was started on three 'fronts'. In the north-west a small British-lndian force entered Assam in an attempt to retake the province from the Burmese. This was defeated by horrible terrain and the May monsoons.

In the west, a small British-lndian force was tasked to defend Chittagong from Burmese Arakan, and it was her the British suffered a major defeat on the Naaf River. In the south, a large British-Indian force of 10,640 men landed and occupied a deserted Rangoon. Expecting the population to provide provisions, the British found the place lifeless, and could not now advance until the navy brought supplies from India. During April and May the Burmese forces gradually built up around Rangoon, forever creeping forward by building stockades overnight in the jungle and continually harassing British pickets with random musketry. The onset of monsoon rains in May did not deter this activity on either side, and the British commander, General Sir Archibald Campbell, delayed taking offensive action until the end of May in order to allow the Burmese to approach nearer, thereby reducing the distance required for his troops to march through the jungle.

On May 27th Campbell advanced north from the outskirts of Rangoon, and catching the Burmese unawares, advanced nine miles through swamp and jungle in pouring rain to arrive on the plain of Joazoang, this setting the scene for the following battle.

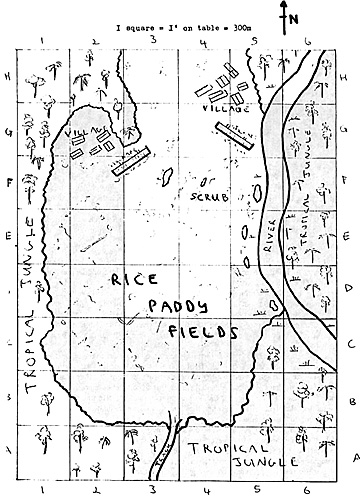

The Terrain - The British emerged from a jungle track into a narrow plain filled with rice paddies, all about 12 18" (30-45cm) deep in water. The boundaries of the paddy fields were marked by low bushes. The combined effect reduces movement by half for troops that wish to remain formed.

Troops willing to become unformed can move at up to I speed. The jungle consists of typical tall rainforest, palm trees and thick undergrowth, with swamps and large ponds near the river. About a mile from the south end of the paddy fields were two villages, consisting of several log built houses with thatch roofs. Just south of the villages are clumps of shrubs and bushes, most about knee high. These surround occasional ponds, and lead up to two eight foot high teak stockades, half hidden by scrub and trees. These stockades have a raised firing platform and loopholes for musketmen, and are large enough for 250 men each, although not all can fire simultaneously.

There are only two narrow exits at the rear of each stockade, large enough to exit one man at time. The river is unfordable, and the tropical jungle is impassable to British troops. The stockades were considered formidable by the Burmese, but in practice the more resolute British found them easy to storm, so they should count as attacking a barricade or wall rather than fortifications.

The Weather - It is the start of the monsoon season, and it is raining heavily throughout the day. To the Burmese it is welcome, as it waters their paddy fields, and they are used to it. Their powder remains dry whirs in the stockades and buildings. To the British, the rain prevents firing in the open, but didn't dampen spirits an' as they are keen for a fight after being cooped up in Rangoon for six weeks. The sheets of rain do reduce visibility to 1D6x 100m per move, and as a result the Burmese player can keep the stockades hidden until the British are within 100m.

British Forces - These consist of a detachment from the 13th, 38th and 89th and/or 41st Line Regiments, under the overall CinC: General Sir Archibald Campbell. 1 Light Company (of a Line Regiment): 45 men, skirmish trained 3 Line Companies @ 65 men approx. Command staff: 1 General, 6 staff, horses. Such a small force could be fielded at 1:1 or 1:2 perhaps, with a set of rules designed to cover platoon level operations in the Napoleonic battlefield. Campbell was the sort of of ficer quick to seize an opportunity and braved enemy fire without flinching, so should be given some sort of command bonus.

The British start in march columns or line in row B in the clearing (see map). Orders are to advance north to engage any enemy, some of whom are just visible mustering in row G. Due to the rain, all muskets count as unloaded and cannot be used except inside buildings and stockades. There are no reinforcements, however two miles to the south are 250 Sepoys (Madras Native Infantry) guarding a 6pdr gun and a 5.5" howitzer without limbers, the crews exhausted after manhandling them seven hours through the jungle. A messenger could be sent to call on these but it is unlikely they would arrive in time, it taking even a fast messenger an hour to cover one mile in the jungle track.

Burmese Forces - Hidden in F3 and G4/G5 are teak stockades, each manned by 250 irregular infantry musketeers and spearmen. All are armed with a dab, a short machete type sword. Musketeers have matchlocks. The stockades have sufficient loopholes to allow around 40 men to fire simultaneously, although the Burmese were not trained to fire volleys. The other men in the stockade would pass forward reloaded muskets to those firing. Deployed in between the village H4 and G3 is the bulk of the Burmese force, perhaps another 1000 irregular infantry in four 'battalions' each of 250 men. One of these units is matchlock armed, the rest have spears. No artillery or cavalry is available, the only mounted men being infantry of ricers. Orders are to destroy the 'foreign devils' with utmost ferocity. The Burmese were totally ignorant of the capabilities of British Napoleonic style line infantry and were convinced of the infallibility of their stockades, which were effective against other Asian irregular armies. Officers showed no particular skill so shouldn't have much of a command bonus.

The Actual Battle - The four British companies advanced in line towards the villages, companies echeloned one behind the other. At 100m from the villages, they were surprised by fire from the previously unseen stockades. Aware of the bulk of the enemy deployed further north, Campbell immediately ordered one company to halt in the centre, whilst the other three stormed the western stockade. The British were not halted by musketry, rice paddies or the eight foot (2 and one-half m) high stockade and they quickly climbed onto the firing ramparts. The defenders, pushed back against the two narrow exits became a seething mass unable to flee or charge. Using their muskets for the first time, the British mowed down the Burmese in heaps. Individual survivors charged the British with spear and clubbed musket, but were easily dispatched by bayonets.

Leaving 2-300 Burmese casualties, the three companies then turned and charged the other stockade. A fiercer, longer fight produced a similar result. Whilst the fighting in the second stockade was taking place, the Burmese main body decided to advance against the sole British company in the centre. As they charged forward the defenders of the eastern stockade were routed, and the three British companies charged out, heading for the flank of the main Burmese force. Seeing this the Burmese force turned and fled into the jungle, leaving the British in possession of the plain. After collecting their small number of casualties, the British returned south, leaving over 400 Burmese dead behind.

Figures - The British wore bell-topped shakos and a Napoleonic style uniform of red and white, although dress regulations in this far flung campaign were never strictly held. Many colours were worn such as blue calico trousers, some even had tartan trousers. Officers wore a variety of headgear, from oilskin shakos to forage caps.

In 25mm, Wargames Foundry are likely to produce the correct figures, and in 15mm check out Irregular and Two Dragons. For Burmese troops, Indian wars irregulars without shields are suitable. For "uniform' details, see Osprey MAA224 Queen Victorias' Enemies (4), the Burmese Dacoits shown being typical of Burmese irregulars. Donald Featherstone's book Victorias' Enemies has a useful chapter on the Burmese, but the most useful work has been The Burma Wars 1824-1886 by George Bruce published in 1973 by Granada, ISBN 0-246-10547X. Alternatively you can wait several years for my book on the Burmese Army 1780-1855) to be published, but I'd better finish writing it first.

Back to Table of Contents -- MWAN 84

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Hal Thinglum.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com