How powerful was artillery during the era of smoothbore cannon and smoothbore muskets? What was its impact on the battles of the Napoleonic wars? If you review the game rules available from the last twenty years, the calculation of that power is fairly uniform. Pas de Charge!, written in 1977, presented the firepower of an eight gun battery as equal to a battalion volley (600 men). Even with several fire combat modifiers, an eight pound gun is presented as having the fire effect of 60 to 100 men firing muskets.

This convention was followed with Wargames Research: Group's Wargames Rules, 1685-1845, a fire unit of 80 men being half as effective as two guns. This changes somewhat with Newbury's Fast Rules for Napoleonic & Crimean Wargames. This later set of rules has 4 guns as effective as a battalion of infantry, a ratio of 150 men to one gun.

The more recent rules follow this ratio: Vive l'Empereur, Napoleon's Battles, Empire , and Guard Du Corp all calculate a piece of artillery as having the firepower of about 150 men armed with muskets, even though each has very different fire mechanics. I couldn't tell you when this convention was created, or how it is that all the game rules I reviewed follow this convention.

Like all conventions, this one should be questioned: Is the ratio of 150 to one or less a reasonable representation of artillery firepower in relationship to muskets? Conventions are created and honored often because the convention is true, other times it goes unexamined for a lack of time or it is not deemed important enough to warrant the effort. Because it is a fascinating question, lets explore the truth of this convention.

I could not find any military historians that agreed with the rules designers. The historians claimed artillery accounted for 40 to 60 percent of all casualties during the Napoleonic wars. (1:8 & 7:65) The methods for arriving at those percentages are based on the observations of contemporaries. The accuracy of their observations are unprovable. However, more reliable observations conclude World War I artillery as THE decisive arm of battle, inflicting 60% of all losses between 1914 and 1918. Keegan, in his Face of Battle, believes the only difference between cannon effectiveness in 1815 and 1914 was the time and distance needed to inflict the losses. It took Napoleonic batteries three hours to cause ,he bloodshed a W.W. I barrage could deliver in twenty minutes (8:305) Even so, Napoleon dubbed the cannon the "queen of Battle" and stated that "great battles are won with artillery". (9:vol XXXI,428)

Now, I have never seen a Napoleonic battle played out on the tabletop where artillery won the game, or inflicted 40 to 60 of the casualties. My experience has been that artillery well handled a game tallied no more than 25 to 30 % of the losses. This is much less than historians seem to be telling us was the norm. I suspect tnat this :.s partly true because few wargamers want to see their infantry and cavalry blown apart without any decisive charges or thunderous volleys. Napoleon often used artillery to make those volleys and charges foregone conclusions... What information can we examine in establishing the historical weight of cannon fire to musket fire?

Well, there are several comparisons we can explore and I would like to take them one at a time:

1 . The relative casualties caused by cannon and musket fire:

We have already mentioned this generally accepted conclusion. For example, both Keegan in The Face of Battle and Hughes in Firepower determined artillery accounted for 50 to 60% of battlefield casualties in the 19th Century. Musketry another 25 to 35% with hand-to-hand combat involving no more than 10 to 15%. This is all from the accounts of medical men counting the types of wounds found after battle. It is not clear, for instance, how these soldiers would tell the difference between a wound caused by a volley and canister when both used the same lead balls. While these "counts" support the 60-35-15 ratio, the evidence is weak. It suggests that 6 of every 10 casualties in our games should be from cannon. It seems a little too much to accept at face value.

2. Ordinance tests conducted during the period:

The question of the effectiveness of artillery and musketry was certainly an important one to the military men of the day. There were a large number of ordinance tests carried out during the Napoleonic era, some of which were: The French in 1756 (11:88), the Hanoverian Army in 1790 (10:60) and the Prussians before 1805 (3:342). The most extensive were carried out by the British in 1803 and 1811, B.P. Hughes using them as the basis for his study Firepower. In all the tests, battalions and batteries fired at sheets 100 to 200 feet wide representing the front width of infantry and cavalry units. The targets were set at various distances to judge effectiveness.

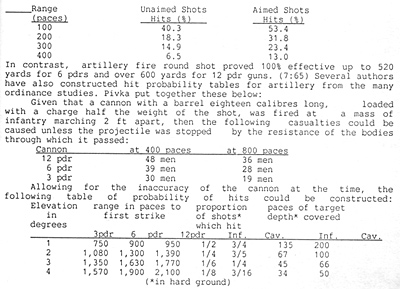

The musketry and artillery results from 1756 to 1811 are very uniform. It proved necessary to place the cloth targets within 80 yards of unaimed battalion volleys for 50% of the shots to hit the target. Aimed volleys could achieve up to a 75% hit ratio. Below is a chart taken from von Pivka's book compiling the 1790 Hanoverian tests (10:73): The results of two groups (one trained to aim, the other not) were then compared after each had fired 1,000 rounds at each of the ranges shown below; the target was representing a line of cavalry:

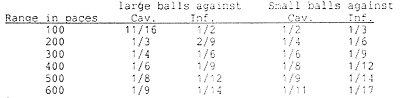

Canister was even more capable: a 6 gun battery of 6 pounders might cause 150 to 200 hits at two hundred yards, which proved to be equal to 4-6 infantry battalions at 150 yards! Again Pivka gives ratio for canister from the 1790 tests:

The following table gives an idea of the effectiveness of canister at various ranges, expressed as fractions of the total number of canister balls fired which would hit the target: (about 50 large balls and 100 small to a shot)

If we compare artillery effectiveness to musketry, EVERY ordinance test for canister and volleys demonstrates that one gun could put as many holes in the target as 300 to 500 infantry! Not only that, but artillery canister could outrange infantry by several hundred yards... and this is not counting the damage artillery could do with round shot.

Infantry could fire between 2 and 5 rounds a minute in formed unit volleys. A six gun battery could throw out 10-15 rounds a minute which means that for intense periods of fire, the damage still comes to about 400 men to 1 gun if counting just canister. With round shot at 800 yards, a 12 pound battery could hit 240 men with one volley including the pass through, the equivalent of a battalion volley at 150 yards.

It is easy to see that if we only doubled the ratio given in game rules so one gun is equal to 300 infantry firing canister and 150 to 1 for round shot, this would be a fairly conservative expression of the ordinance tests between 1756 and 1811. But of course, this is under perfect conditions...

3. Battlefield conditions and relative training:

The influence of battlefield conditions on engaged artillery and infantry, regardless of how bad, would tend to equal out in the end. Smoke caused from a volley would mask a target as well as cannon fire. If canister could to hit a few infantry or cavalry several times, volleys would do the same. If artillery might have a difficult time finding a line-of-sight to the target, so would infantry. Both artillerists and battalion leaders would attempt to maximize their fire as best they could. However, their ability to do that would be determined by their training and experience. Without a doubt, here is where artillerymen were head-and-shoulders above the infantryman, officer and private.

The artillerist was a selectively chosen, highly trained and better paid soldier. Where many infantry would fire their muskets five or six time a year in practice, artillery would practice as much in a month. Where infantry were not even trained to aim, artillery men had specialists for targeting. Artillerists in the field during the Napoleonic wars averaged two years experience, infantry less than half that.( 8:171; 13:83) There is a convincing superiority of the artillery arm over the infantry in battle readiness and training.

4. Equipment reliability:

If the comparison in relative training for the two arms is striking, the reliability of the cannon compared to the musket is even more impressive. Up to 25% of all musket fire was lost to misfires, where artillery misfired perhaps 5% overall. (7:165) The performance of cannon and musket must also be compared by contrasting simple items like the number of moving parts required to fire. Cannons contained one: the block or elevator; while flintlocks required six counting the flint vise. The cannon was a simpler and more dependable weapon. (6:56)

The quality of the musket is another issue. An officer, urged by prudence to be known only as An Officer Of Infantry, published a booklet in 1796 entitled A SKETCH OF THE PRESENT STATE OF THE ARMY in which he wrote:

- "it may not be improper to mention the badness of the flints, and .the softness of that part of the pan-cover of his firelock that the soldier calls the hammer. This is so general, that ... after ten or twelve rounds of firing, you will find at least a fifth part of. the cartridges have not been used( i.e.,have failed to go off owing to insufficient sparks); consequently one man in five would be useless as to any real effect. This we see every day at field-days and reviews; and upon service, I have seen soldiers try their pieces again and again, to no avail."

5. Professional Commentary:

Another approach to determining arms effectiveness is to discover what the combatants themselves had to say about the two weapons.

Keegan has made a cogent argument for artillery fire being the deadliest and most demoralizing form of attack infantry and cavalry had to undergo in battle. One soldier is quoted as observing,

- "Cannon shot was the thing we feared the most and sought to avoid at all costs."(8:159-161) This isn't surprising if we accept that artillery was the cause of half of all casualties, all caused at great distances compared with the other arms. Muskets on the other hand, were considered as inadequate by the soldiers themselves. Even infantry tactics were based on the musket's ineffectiveness: massed volleys.

Some of the most scathing criticisms of infantry fire came from the Britons, the wielders of the famous "Brown Bess", renown for their infantry volleys and fire discipline (1:91; 6:114):

An author who preferred to be known only as A Colonel in the German Service(i.e. in the British army serving in Germany during the Napoleonic Wars), wrote a tract published in London in 1805 (after almost a century of Brown Besses!) entitled A Plan for the Formation of a Corps Which Never Has Been Raised as Yet In Any Army In Europe; acidly he observed (italics in original):

A soldier's musket, if it is not exceedingly badly bored, and very crooked, as many are, will strike the figure of a man at 80 yards-it may even at 100 yards. But a soldier must be very unfortunate indeed who shall be wounded by a common musket at 150 yards, provided his antagonist aims it at him; and as to firing at a man at 200 yards, you may as well fire at the moon... in general service, an enemy fired upon by our men from 150 yards is a s safe as in St. Paul's Cathedral.

The real effectiveness of musket volleys depended on how close troops would allow the enemy to come before volleying. It is no wonder that All Napoleonic military regulations taught that commanders should only open fire on the enemy at 40-80 paces.(2:79; 11:104).

6 Comparing casualty figures:

Playing with numbers is fun and they can reveal pertinent information. If using casualty figures from Napoleonic battles is clear that flintlocks were very poor weapons compared to cannon. At Wagram, the Austrians suffered 37,146 casualties. The French had 488 guns and 130,000 infantry. Assuming all infantry and artillery were engaged, we can play with the numbers:

If the infantry caused a liberal 50% of the casualties (18,573), that is only 72 hits for every 600 infantry for the ENTIRE two day battle, or one hit for every 8.3 men firing. If you allow artillery a conservative 40% of the casualties (14,858), this is 38 hits for every cannon, or 228 for every six guns. This comparison, even with the weighing of the historians' percentages in favor of musketry, comes out to one gun being equal in fire effect to 312 men, the lower end of the range of comparisons of 300-500 to one we already established from the ordinance tests.

Reviewing ordinance tests, reliability, training, contemporary opinion and casualty figures all point to the significantly greater effectiveness of artillery compared to musketry. It should be clear that game rules have underestimated artillery effectiveness. There are several things that can be done to remedy that.

Before making any changes your rules, play a few games while keeping track of the casualties caused by artillery, musketry and melee. You should be able to establish what the ratios are for the different forms of combat. It is a fascinating exercise. If they are not about 50% for artillery, 35% for musket fire and 15% for everything else, consider the following:

- 1. Increase the effectiveness of artillery fire from 50 to 100%, noting the differences it makes in how your games are played and the casualty ratios.

2. Increase the morale impact of artillery fire on formed units.

Play with the results. It has been my experience with the changes to artillery effectiveness, the game dynamics alter the players' tactical decisions, mirroring more closely the those of the actual Historical participants. Try it and see.

Conventions should be questioned. We often let our misconceptions and desire for tabletop glory cloud, what is historical reality, even at very fundamental levels. Because we want to experience the tactical challenges faced by Napoleon and his contemporaries, we need to look closely at what they tell us about those challenges. Every so often, we need to ask basic questions and reexamine the answers... just to keep things interesting.

REFERENCES

1. Depuy, T.N. Numbers, Predictions and War, Bobs-Merrill 1979

2. Anonymous, Reglement concernat 1'exercise et las manoveuvers de

l'infantrie du premier aout 1791, New Edition, Paris 1821.

3. Chandler, David, G., The Campaigns of Napoleon, Macmillian Co., New

York, 1966.

4. Du Picq, Colonel Ardent, Battle Studies.

5. Dupont, M. Napoleon et Ses Groqnards, Paris, 1945.

6. Held, Robert, The Age of Fire Arms,Bonanza Books, N.Y.

7. Hughes, Major-General B.P., Firepower, Charles Scribner's Sons, N.Y.

1974.

8. Keegan, John, The Face of Battle, Vintage Books, N.Y. 1976

9. Napoleon I, Emperor, Correspondence de Napoleon ler, 32 vols, Paris, 1858-1870.

10. Pivka, Otto von, Armies of the Naooleonic Era, Taplinger, 1979.

11. Quimby, Robert S., Background on Napoleonic Warfare: The Theory of

Military Tactics in 18th Century France. Ams Print, 1957.

12. Richardson, F.M., Fighting Spirit: Psychological Factors in War,

Crane-Russak Co., 1978.

13. Rothenburg, Gunther E., The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon, London, 1977.

Back to MWAN #67 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com