In the year 47 BC, while Caesar was occupied in Egypt with the remaining Pompey forces and being besieged in Alexandria, the son of Mithridates VI named Pharnaces invaded lesser Armenia and the Kingdom of Cappadocia. As Caesar's forces were tied down and under great military pressure, Pharnaces seized an opportune moment to try to regain the territory lost in the Mithridatic wars. Domitius Calvinus, who was governor of Asia minor and the neighboring provinces, sent an ambassador to Pharnaces bidding him to withdraw immediately from these occupied provinces and pay an indemnity to those provinces.

In order to get his point across with more meaning, Domitius Calvinus advanced upon Pharnaces with his veteran 36th legion and two allied Armenian legions built upon a Roman style legion and armament but lacking the skill and history. He sent Sestius to Pontus where a hastily formed legion was mustered -- in all probability from Roman citizens and possibly military settlers. Patisius collected auxiliary forces from Cilicia, and all assembled at Comana where they were mustered.

But Pharnaces was not dismayed, as he knew that two other veteran legions, the 6th and the 35th, had been sent to Caesar in Egypt and all that was left was the 36th legion to use as a nucleus of an army. So Pharnaces withdrew from Cappadocia which was too long of a distance from him to protect and continued to occupy the Armenia province which lay close to his own kingdom, saying that it was his father's old territory, playing for time and the hope that Caesar would be crushed in Egypt. Domitius insisted upon Pharnaces withdrawal and immediately set out with the one Roman veteran legion, one hastily raised legion from the Pontus district of Roman settlers, two copy cat legions of lesser Armenian origin (the 27th and 37th), several thousand auxiliary light infantry and some two thousand cavalry of Roman/allied make-up, but of poor quality.

Now Domitius' route was along the higher ground as his army was greatly outnumbered by Pharnaces' cavalry and his infantry feared them. By this it would seem to indicate that Pharnaces army was very superior in cavalry numbers and that part of this cavalry was in all probability cataphract in nature. The route taken between Comana to Pontus was probably a wooded ridge mentioned in Caesar's commentaries from Lesser Armenia and Cappadocia. The very nature of a hilly wooded terrain would be conducive for infantry and difficult for cavalry to seize any advantage.

The forces of Pharnaces must be estimated and in this I open myself up to attack, but I believe that the forces of Pharnaces were greatly reduced from what was available to his father Mithridates VI. The number of Phalangites in all was no more than 10,000 to 15,000, with another 10,000 light infantry that the area had in abundance, with possibly another 20,000 medium infantry of dubious quality and worth. The cavalry would have stayed somewhat more constant with perhaps 10,000 men, of which perhaps 2,000 were true cataphract horse. We will see later in the article why I believe Pharnaces went back to the traditional phalanx and abandoned the mock legions his father tried to develop in the Third Mithridatic War.

Pharnaces continued to stall and delay, sending envoys to treat with the Roman governor. But all their efforts were in vain as the Roman governor Domitius continued to settle for no less than Pharnaces' withdrawal from the occupied province. Domitius' forces continued to advance upon Pharnaces by a series of forced marches to Nicopolis, a small town in Lesser Armenia, 7 miles distance from which he pitched camp.

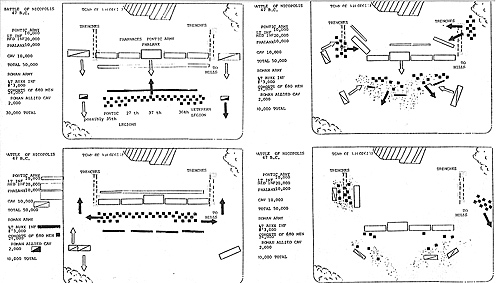

Pharnaces' army lay in quiet repose. Suddenly Pharnaces took action and set an ambush that was foiled by Domitius delays, whereupon Pharnaces withdrew to Nicopolis again. Domitius now advanced upon the town and encamped not far from it and Pharnaces drew up his army in line of battle. Pharnaces also constructed two straight trenches, four feet deep and not spaced very far apart on each flank of his infantry, but between the infantry and cavalry, while posting on the outside of the trenches his cavalry forces. In the center of his line was drawn up in all probability his Heavy Phalanx, with medium infantry to either side and the light skirmisher infantry were drawn up along the entire front. No mention is made of scythed chariots. We do know he had them, but they were not perhaps used in this engagement.

One interesting thing to note is that he had trenches dug on either flank. I believe that he feared the more maneuverable Roman infantry as Pharnaces' cavalry was far superior to the Romans' in numbers and quality. The only reason he would fear a flank attack would be if his infantry still fought in a phalanx style formation. For if his infantry still fought as mock legionnaires, their cohort formation could rapidly alter to the threat, but if on the other hand, the infantry was in a deep phalanx formation it would almost be impossible to shift in time, unless something delayed the attack and alerted them to the attack so they could change face. This is what the ditches were for, not to stop the Romans, but to slow them down and disorganize their ranks, giving opportunity to counterattack. Another interesting thing not mentioned is that Pharnaces had decided not to advance his infantry beyond the trenches indicating a fear for the safety of infantry flanks. This is a strange behavior for an army superior in quality and quantity of cavalry (remember the heavy cataphracts).

The Roman governor Domitius drew up his forces with the veteran 36th legion on the right wing and the Pontic legion of settlers on his left, while the two less reliable Armenian legions he concentrated in the center of his line, positioning a few of his own cohorts behind them in support. Again, strong indication that these troops were not up to the standards of a normal roman legion and an indication that he had to steady them with more reliable troops. Domitius had to stretch his line in order to counter the superior length of the Pontic Army, but in so doing weakened his own line. While Domitius posted all his auxiliary light infantry to his front they were greatly outnumbered, as were his cavalry posted to either flank.

The action soon began with Domitius' cavalry not being mentioned again and in all probability it was either routed or retreated from the battle to draw Pharnaces' cavalry after them. What cavalry remained on the right flank where the 36th legion was were roughly handled as the legion advanced along the outside of the trench up to the city wall. While the Pontic legion on the left attempted to cross over the trench, it was pinned down and overwhelmed (again, due to disorder, etc.). The legions in the center of the line offered little resistance and broke (Again, that the cavalry of Pharnaces attacked them from behind is a strong possibility). While the 36th legion was attacking the King's left rear, his army everywhere else lay victorious. Only then did the 36th legion march off the battlefield in a circle formation to the nearby hills where Domitius rallied the few remaining survivors.

The losses to the Romans were severe, with only the 36th legion suffering light casualties of 250 men. The Pontic legion was almost totally lost and a large percentage of the two Armenian legions was killed. Of the almost 30,000 man army, only about 12,000 escaped destruction. The losses to Pharnaces' army are not mentioned, but could not have been as severe as the Roman losses.

Domitius tried to use the flexibility of his legions to do a double envelopment as at Cannae. His main reasons for failure are three-fold. The first is that the quality of the legions he had to work with was under par. Second, the enemy's cavalry was never checked and so posed a threat to return to the battlefield at an inopportune time, which they probably did to eliminate the two center legions. Third, his troops did not move as quickly as Hannibal's cavalry at Cannae and had the extra obstacle of the trenches to negotiate, throwing his troops into considerable confusion as happened to the Pontic legion when it tried to cross them with armed opposition.

Wargaming the Battle

This indeed would be a tough one for the Romans to win, but should prove a challenge for an experienced player. I would downgrade the quality of the two center legions and take a 2" movement off the Pontic legion to slow its movement down and force it by victory condition to cross over the trench in disorder status. Or the Romans could always fight them head on and see what happens?

If the Roman player finds this scenario much too difficult, he can try adding the veteran 35th legion to the Roman side, as it had just embarked on ships to sail to Egypt. The 6th legion had already landed in Egypt and would not be available for operations. If the Roman player still loses, one could try different tactics than were done at the actual battle.

As for Pharnaces, one could always add a unit of scythed chariots (approximately 100 strong for whatever scale you use). This should liven things up quite a bit. Other than this, Pharnaces' tactics seemed well thought out by allowing the Romans to exhaust themselves by forced marches across difficult countryside and advancing to Pharnaces' position where his troops were well rested. He took necessary precautions to guard the flanks of his less mobile infantry and did not advance beyond the trench line until the Roman line was breaking up and in disorder.

Maps

Back to MWAN #67 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com