There is no fighting unit in the world whose history and legend has been built more on the heroic last stand than the French Foreign Legion. The anniversary of the battle of Camerone--April 30, 1863--is the Legion's most important holiday' celebrated every year at every Legion base and outpost with the reading of the story of the battle.

It was an epic encounter, in which 48 Legionnaires stood off 3,000 Mexicans for the better part of a day. When only five Legionnaires were left standing, they fixed bayonets and charged the startled Mexicans.

A close runner up for honors in the catalog of heroic Legion stands is the battle of El Moungar. (Dien Bien Phu, from the more modern era, and Bir Hakeim, from World War II, are others.) In this article, I'll try to give some of the historical background and suggest some guidelines for refighting the battle. In Part II, I'll present a comparative analysis of my refights of the battle using two different rules systems, The Sword and The Flame and Hal's March or Die.

El Moungar

Larger Version of Map (slow download: 112K)

Larger Version of Map (slow download: 112K)

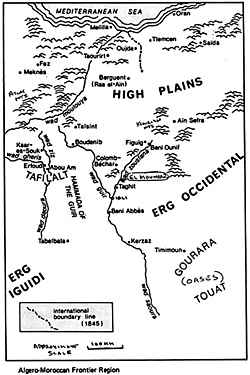

El Moungar, which is a plain, lies in an area referred to by the French as the South Oranais. Whether the area was properly within the borders of Morocco or Algeria was anyone's guess, since the Treaty of 1845, between Morocco and France, fixed the Moroccan-Algerian boundary only from the Mediterranean to a point some 68 miles inland (see map), and left the remaining territory south of there undefined.

It is true that the inhabitants of the area's villages and oases gave their allegiance to the Sultan of Morocco, at least in religious matters. But despite the close relationship of spiritual and temporal matters in Islam, the inhabitants apparently steadfastly refused to submit to the Sultan's civil authority, at least insofar as such authority required the payment of taxes or military service. The area was part of the bled es siba, or land of dissidence (to the Sultan, not the French). The South Oranais was technically not part of the Sahara; it did border on the desert and one writer referred to it as pre-Sahara.

Consequently, it would be a mistake to think of this region as one of sand dunes. In fact, three rivers--the Wadi Ziz, Wadi Guir and Wadi Zousfana--running down from the Atlas or Ksourian Mountains (although running underground at times), provided enough water to permit the establishment of villages, towns and oases. An oasis, in this context, is substantially more than just a watering hole. An oasis could run for miles and include several villages and thousands of date palm trees. The Tafilalet, for example, was 13 miles long and nine miles wide. Figuig consisted of seven separate walled towns, or ksours.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, the French expanded into this area and areas south of it, as well as into the Tuareg country in the central Sahara. Not surprisingly, French expansion was met with varying degrees of resistance. Of course, as all good gamers know, when combat occurs, logistical considerations cannot be far behind. The French discovered that it was a mammoth task to keep their new posts supplied.

Camel Caravan

In 1903, a massive caravan of 3,000 camels escorted by 2,000 French troops, was put together to resupply the French posts in the South Oranais, from Figuig all the way down to Igli and thence to the Touat oases. The convoy had to be split into three sections, with the second leaving two days after the first and the third leaving two days after the second, to allow the wells along the way time to refill. A half company from the 22nd Mounted Company of the Second Regiment of the French Foreign Legion, together with a squadron of some 30 Spahis, was detailed to provide rear guard support to the second echelon.

The Legion detachment consisted of 117 men and officers. The term "mounted" here is something of a misnomer, as their mounts were mules and two men shared a mule, with one riding the mule for an hour at a time, while the other walked. The unit had marched through the night of September 2-September 3 and, at 9:30 a.m., on the plain of El Moungar, broke for breakfast.

In L'Armee d'Afrique, there is a picture of the battleground. I sent a photocopy to Hal with this article, but I do not know if it can be effectively reproduced. If it can be, I hope he does so. It shows ground that is completely barren of vegetation, but it does not appear to be sandy; rather, it appears to be quite solid under foot. The ground undulates quite dramatically; it certainly has the same topography as sand dunes, and it is easy to see how an ambush could be sprung in such terrain. One writer referred to it as consisting of flinty hillocks.

What happened, at least in broad terms, is not in dispute the Legion/Spahi escort was attacked by a war party composed of men from several Arab and Berber tribes. Unfortunately, the wargamer-turned-historian does not have an easy time of it in figuring out exactly how the battle was fought. Having no access to the official battle reports, one can only rely on secondary works.

However books on the Legion tend to be more journalistic than scholarly and, if not downright contradictory, are sometimes less than completely satisfying. The one writer who approached the subject in true scholarly fashion, Ross Dunn (see bibliography at end of article), who has obviously read the actual contemporary reports, has chosen to give only the briefest summary of the battle of El Moungar. The other sources vary widely in their accounts.

Key Historical Question

A key historical question, particularly for wargamers, is how many attackers were there? L'Armee d'Afrique merely says several hundred, which is repeated by Windrow. McLeave, on the other hand, claims it was 5,000, which was ten times the 500 cited by Kanitz. Dunn mentions 200 mounted warriors. One wonders if McLeave merely added an extra zero by accident.

As the attack is generally thought to have been carried out by some of the survivors ot the massive attack on the French fort at Taghit just a few weeks earlier, and as that force was only 4,000-5,000 strong, it hardly seems likely that there were 5,000 Arabs and Berbers at El Moungar. The 500 number is probably a lot more credible.

A second interesting question is whether there were any camels with the escort party or whether the escort was a true rear guard, following at some distance behind the caravan. Geraghty talks about the animals stampeding once the attack began, but he might have been talking about the mules of the Legionnaires and the horses of the Spahis. McLeave, who continues to be suspect, talks about 600 camels panicking and stampeding, but no other source indicates that camels were there.

Arab Attack

For me, the key historical question concerns the nature of the Arab attack. Were they on horseback or on foot (or both), and did they charge the French or merely fire at the Legionnaires and Spahis from the crests of the surrounding hillocks? How did the French respond? Dunn, as noted, only mentions mounted Arabs. Geraghty talks about the Arabs "charging at will through the French soldiers who had divided into two groups, each on its own hillock," but McLeave talks about wounded men crawling away from the rifle fire from the high dunes.

Just about every account agrees that the Legionnaires attempted counterattacks (unsuccessfully) against the attackers, which only makes sense to me if they were trying to drive the attackers out of good firing positions. It also seems pretty clear that the French were divided into two groups, at least one of which fought its way to a hillock and established a defensive position there, possibly using dead mules for cover.

Windrow says that after a series of courageous counterattacks, they "forted up" on a slight rise behind dead mules. Kanitz writes of two sections of the French half-company going on the assault in an attempt to discourage the attackers and afterwards, of the survivors establishing themselves on two small, rocky hills.

Officers Down Both Legion officers were casualties. The handsome and dashing Danish Lt. Selchauhansen was killed by Arab bullets. Some accounts say he was killed almost at once (Windrow, e.g.), but others say that he lay wounded on the ground, outside the French defensive formation, encouraging his men, even as he bled to death (McLeave). Apparently at least two Legionnaires were killed trying to recover his body.

The other officer, Cpt. Vauchez, was seriously wounded and died the next day. In true Legion fashion, command devolved on lower and lower levels. At the end, Corp. Tisserand was directing the defense. According to Geraghty, he led a bayonet charge to counteract an Arab assault (which may indicate that Legion charges were not used only to clear firing positions, but why is a charge the better defense against an assault as opposed to staying in cover?) and succeeded in driving the Arabs off temporarily. However, Tisserand was also hit by a bullet and killed. He was posthumously promoted to second lieutenant.

The attack lasted until 4:30 or 5:30 in the afternoon, when the Arabs saw the relief party coming and broke off the engagement and withdrew. The Legion suffered 36 killed, including the two officers, and 47 wounded. By any measure, it was a significant Arab victory and so shook the French establishment that a new commander was brought in to take control of the South Oranais province. That man was Col. Hubert Lyautey, "the royalist who gave the republic an empire." Lyautey occupies a position in French colonialism comparable to Cecil Rhodes in British colonialism.

Not only did he pacify the South Oranais, but directed the conquest of Morocco and later became the French Resident General there. More than any other man, he created and shaped French Morocco, relying in no small measure on the soldiers of "ma troupe, ma plus chere troupe" (my troop, my most dear troop), the Legion.

Side Notes

A number of side notes to the battle. For those of you who like to include logistic considerations in your games (are there any of you?), the lack of effect of supply was interesting. Although the Legionnaires had no water for the whole battle (Livre d'Or), presumably since it had been carried off by the stampeding mules (Geraghty), and no extra ammunition other than what they were carrying, and thus had to conserve their ammunition, the lack of water and ammunition did not seem to prevent them, in those deadly circumstances, from holding out until help arrived.

Not one account I read indicated how many Spahis died or survived. Some of them were on picket duty and were among the first killed, while others rode in both directions for help, so there may not have been many left. Although the brunt of the fighting seems to have been borne by the Legionnaires, the lack of concern for the Spahis is surprising.

It is reasonable to assume the attackers were armed with boltaction rifles, although they probably did not have magazine repeaters. The Arab harka which had just attacked Taghit was described in the official dispatches as "well armed" and Dunn maintains that the dissidents (to use the French term) of the South Oranais had modern rifles, mainly Remingtons, by the end of the Nineteenth Century.

Scenario Notes

If you would like to game this scenario, here are some suggestions for organizing it. First, as to terrain, I set up a series of small hills or hillocks along the length of one long side of the game table (I used a 4' x 6' table). More or less down the center of the board is the track to be followed by the French. My feeling is this track should be within rifle range of the crests of the hillocks, so the Arabs can fire at the French convoy, but probably at long range, since one would like to encourage charges.

The track should also be within possible charge distance of the crests, so that Arab mounted units have at least a chance of making melee contact with the convoy on their first move. On the other hand, there should be some uncertainty as to their ability to do this so that the French, seeing them come, might have some time to react. On the other side of the board from the hillocks on which the Arabs appear, I place an occasional hillock, these being the rises to which the French can retreat, if they are able, to establish their defensive formations.

If your table is wide enough, I imagine you can provide for yet other groups of hillock: behind these which the Arabs could reach in circling movements, so subjecting the French to a cross fire, but my table is not wide enough to permit such movements.

As to forces, I basically utilize a three-for-one ratio. Thus, my French unit is composed of 17 men mounted on mules and 17 troopers on foot, with two horse-mounted officers and an NCO who has a mule to himself. To represent the Spahis, I use 10 mounted soldiers and one mounted officer.

Just for the sake of atmosphere, I throw in about a half dozen heavily-loaded pack camels. They play no part in the scenario and, once the attack is joined, I pretty much just remove them from the board, but they sure do look good during the opening turn.

Camels as Wildcards

Parenthetically, if I could feel confident that camels were indeed present, I might be tempted to use them as a kind of wildcard. In the battle of Tit, where one French officer and his

Goumiers (partisans) defeated the Tuareg, the pack camels played a critical role. The Tuareg had attacked the French, had thrown them back, and had them very much on the defensive. The Goumiers were close to panic, firing wildly and using up their ammunition rapidly to no good effect, when a few enterprising Tuareg, individualists to the core, ceased attacking and started looting the camels.

When their brethren saw this they too turned to looting, and they were then cut down easily by the no-longer beleaguered Goumiers. So there is a rationale for using camels as a looting distraction, but I do not do so in this scenario.

For the Arabs, I started with 168 figures, representing 504 men, but the two scenarios I played convinced me that the Arabs outnumbered the French too greatly. At any rate, I had per TSATF, I had one 12-man camel unit with rifles; one 12-man camel unit with spears; two 12-man horse units with rifles, three 20-man foot unit with rifles; and three 20-man foot units armed only with melee weapons (swords or spears).

My scenario lasted seven turns, or one hour per turn. The time/distance scale may be a little off here but, quite frankly there was no way the French were going to survive more than seven turns and would be lucky to survive seven. In my scenarios, the reinforcements are assumed to automatically arrive at the end of turn seven, ending the game. However, if you prefer to have shorter turns, say half-hour turns, you will need to make some adjustments to handicap the Arabs, or utilize different game mechanics that give the FFL a chance.

During the first turn, when playing TSATF, I permitted only Arab movement to simulate the effect of surprise. On turn one, all Arab mounted units were available and started just behind the crests, determined randomly. I subdivided the board into six sections and rolled a D-6 for each unit to determine where it started. The foot units arrived on subsequent turns. On each turn, starting with turn two, I rolled dice for each foot unit. Each unit had a 25% chance of appearing on turn two, a 33% chance of appearing on turn three, a 50% chance of appearing on turn four, a 75% chance of appearing on turn five and any remaining units appeared on turn six. Placement on the board was again determined randomly.

With respect to the mule-mounted company, I essentially used TSATF mounted rules, whereby one die could be used for dismounting. I also provided that one die could be used to kill the mule for cover. With March or Die, each such action equaled one inch of movement. Also, since TSATF does not provide a movement rate for the mule-mounted companies, but since they were demonstrably faster than foot units (but certainly not as fast as true cavalry units), I modified the TSATF foot movement charts so if the infantry movement rate was three dice, e.g., the mule mounted infantry could move at the highest three of four dice.

In Convoy

Finally, my initial setup was designed to please me aesthically and to help produce a historical result. Rather than start with the French dismounted and at rest, I started with them in convoy. However, my convoy was stretched out on the board in three separate, essentially evenly organized groups.

This resulted partly from my misreading of the battle. I recalled that the defenders were split into different groups, but I remembered it as three groups instead of the actual two groups, probably confusing it with the breaking up of the convoy into three parts. My thinking was that if the French figures were all grouped together at the start, upon attack they would quite naturally and easily form one defensive square. I could then lose the experience of managing two separate smaller squares which, conceivably, could try to link up and of managing the Arab attack on separate defensive positions.

From a game design point of view, I realize this is a major philosophical issue upon which gamers of goodwill can disagree. Certainly it's a valid approach to simulate the actual French disposition and let the chips fall where they may. As I said, I was just more interested in seeing what would happen to the groups.

The scenario also required some additional rules for melee and the mounted company. First, no fire is allowed while mounted on a mule. If forced into melee while on a mule, the Legionnaire has a -2 DRM if attacked by Arab horsemen and a -1 DRM if attacked by Arabs on foot.

Also, there is no positive DRM for mounted Legionnaires based on formation. On the other hand, if Legionnaires are prone behind mules, they are Class IV targets for TSATF purposes or in hard cover for March or Die purposes. If they are kneeling behind mules, they are Class III targets or in soft cover. Obviously, these advantageous target classes do not count if they are being fired down upon by a mounted Arab or Arabs on higher ground (if the dead mule does not interfere with the line of fire).

Melee

As to melee, were one to follow the TSATF rule that melee continues with a rematching of survivors until one side has no one left, the scenario would be over very quickly indeed. My modifications are as follows:

- No rematching of survivors (however, initial melee can include up to three attackers against one defender).

- After a melee, on the next turn the Arabs test morale (March or Die) or test for Close Into Melee per TSATF, before movement. They remain in melee on a role of one to four if a leader is in front; if not, they remain in melee on one to three.

- If the unit fails, use the March or Die table to determine results, regardless of which rules set you're using, but rally per TSATF Pinned table. (The March or Die table (simplified) is as follows:

-

1 = rout 4D6;

2-5 = fall back 2D6- reroll - 1-3, backs to enemy

4-6, facing, with 50% chance of going prone - If Arabs lost more men in previous turn's melee than FFL, -1 DRM to morale roll.

- If Arabs fail, FFL is free to move; if not, FFL is locked in melee--no fire phase, just melee. Other Arabs and FFL can join melee per normal rules.

Wounded

Finally, with respect to the wounded, I use the Indian Mutiny Skirmish Rules for the wounded in melee (see my article in MWAN No. 48), but for fire casualties, I use the regular TSATF procedure, except that a second black card in a series is a second wound on a soldier previously wounded in that series, resulting in a kill. For example, if the Arabs have four hits, and the cards turned over are a heart, a diamond, a spade and a club, the Legion suffers one killed from the heart, one wounded from the diamond, one wounded from the spade, and the club--the second black card in the series--means one of the two Legionnaires who were just wounded suffers a second wound and is killed.

Next time' I'll let you know what happened when I refought the battle twice on a solo basis, once with TSATF and once with March or Die.

Bibliography

Jean Brunon' Georges-R. Manue and Pierre Carles, Le Livre d' Or de la Legion Etrangere (Charles-Lavauzelle: Paris, 1981). This is a must-have book for all Legion freaks. A large-size paperback book of 400 pages, it is chock-full of photos, drawings (several in color), history, stories, insignia and details.

Ross E. Dunn, Resistance in the Desert (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, 1977). A very scholarly, mainly anthropological/sociological study of the tribes of southeast Morocco. This is not an easy read, but it does have some fascinating information.

Tony Geraghty, March or Die (Facts on File Publications: New York, 1986). An easy and exciting read. The author puts the history of the Legion in the context of French politics.

R. Hure, H. de la Barre de Nautevil, et al, L'Armee d'Afrique (Charles-Lavauzelle: Paris, 1977). Another must have. Same format as Livre d'Or. Tons of drawings and photos. This one will answer all your uniform questions for Zouaves, Turcos, Tirailleur Senegelais and Sahariennes, Meharistes, Chasseurs d'Afrique, etc.

Walter Kanitz, The White Kepi (Henry Regnery: Chicago, 1956). This used to be a standard English language source for information about the Legion, but is a little dated now. More than just a history of battles, it covers aspects of Legion life such as alcohol, sex and homosexuality. For anyone interested, his description of how the French army organized bordellos for the troops is fascinating.

Hugh McLeave, The Damned Die Hard (Saturday Review Press: New York, 1973). I like all books about the Legion, and this one has some dramatic, probably overly dramatic, writing, but the history is pretty poor.

Martin Windrow, Uniforms of the French Foreian Legion (Blandford Press: Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom, 1986). The source for Foreign Legion uniform information. Like an Osprey, but much, much better, with 32 color plates. The narrative is very summary, but Windrow seems to be pretty accurate, and the writing is of the highest quality.

Back to MWAN #53 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com