It is a surprising and little known fact that during World War Two the Soviet Union possessed the largest and supposedly most advanced airborne force in the world. However it is popularly believed that these troops were never

actually utilized in any operation comparative to either D-Day,Operation Market Garden or the Rhine crossings. In fact the Soviets did indeed attempt several large-scale operations of potentially decisive magnitude; operations which have had important repercussions on the development of their airborne component right-up to the present day.

It is a surprising and little known fact that during World War Two the Soviet Union possessed the largest and supposedly most advanced airborne force in the world. However it is popularly believed that these troops were never

actually utilized in any operation comparative to either D-Day,Operation Market Garden or the Rhine crossings. In fact the Soviets did indeed attempt several large-scale operations of potentially decisive magnitude; operations which have had important repercussions on the development of their airborne component right-up to the present day.

The Soviet Union had been among the first to appreciate the full potential of transporting troops by air to battle. However, unlike either the United States or Great Britain, they decided to take the idea one step further--actively sponsoring the promotion of parachuting not only within the armed forces, but also amongst the public.

Consequently,the Osoaviakhim (Society for The Support of Defense and of Aviation and Chemical Construction) tried to capitalize on the public imagination through the manipulation of prestige trips of Soviet parachutists abroad, and the use of demonstration drops during Red Air Force displays.

For example, in 1936 two hundred parachutists were dropped over Tushino in front of a crowd numbering over half a million. Indeed, included in this performance were twenty-five female parachutists using brightly coloured canopies. An a result of this extensive program public jump-towers were constructed in most Soviet cities during the late 1920s and early 30s; thus presenting the Parachute Troops Adminietration (Ilpravlenie Vozduahnodesant-mush Voisk Krasnoii Amii)with a massive pool of eligible recruits.

By 1929 the Red Army had selected the first men to undergo further parachute instruction, and within a year the first full battalion had been formed in the Leningrad Military District. Several of it's men being dropped that year in central Asia as part of an operation against Islamic rebels. While during 1930 the complete battalion participated in that year's maneuvers on the Voronezh ranges. The importance of the airborne forces within the Soviet military establishment increased dramatically throughout the first half of the 19308.

In August 1931 a team of nineteen parachutists were used to secure a landing strip, on which a Tb-1 squadron flew in troops and guns; an exercise which was similarly repeated later that year in the Kiev Military District. 1932 saw an additional three units being created along the same lines as the first, which was now expanded into the 3rd special purpose airborne brigade -- a fully self-contained formation including both parachute and glider-borne entities.

During the 1933 Kiev exercises a battalion-size unit was successfully dropped en-masse from the giant Tb-3 transporte, which could carry a load of up to six tons. Indeed, during this operation they airlifted in lorries, field guns, armoured cars and even light tanks.

As a result of this impressive list of operations, the high command had become convinced that the airborne forces deserved to play a much greater role. Censequently, Air Force chief, General of Aviation Yako I. Alkanis issued a memorandum to all military district air commanders, urging them to collaborate with the subsequent attempt to enlarge the airborne content(Vozdushno Desant-nays Voyska). So that by 1935 the other three units had been upgraded to similar status as the 3rd brigade: one stationed in each of the Kiev, Moscow and Belorussian districts.

This intensive program was culminated by that year's Ukrainian Military District aeneuvers,which saw the dramatic and now famous descent of 2,500 men,in what was obviously a propaganda stunt for visiting military attaches. Amongst whom it made a particularly deep impression on the British officers Martel and Wavell. The latter of which wrote: "This parachute descent,though it's tactical value may be doubtful, was a spectacular performance. We were told that there were no casualties and we certainly saw none; in fact the parachutists we saw were in remarkably good trim,and mostly moving at the double."

This operation consisted of three distinct phases -- Phase one being the dropping of six hundred men who would secure a landing strip; Phase two consisting of of the landing of follow-up aircraft which brought in additional men and equipment; while the third and final phase saw the landing of even more heavy weapons and supplies. Although these 1935 operations were essentially a repetition of previous operations, they remain much more important as a symbolic demonstration of the Soviet Union's relative superiority.

Consequently, the 1935 exercises were destined to be an important catalyst for foreign developments, most particularly in Nazi Germany.

Throughout the mid-thirties the V.D.V continued to expand and play an integral role in the annual Soviet maneuvers: in 1935 a rifle division was airlifted from Moscow to Vladivostok, in 1936 exercises were carried out in both Belorussia and the North Caucasus, while in 1937 two brigades were involved in an operation grandly entitled 'Operations by frontal air forces and the supreme command's special purpose air arm in the opening phase of battle and under the conditions of a developing front.'

This dramatic expansion of the V.D.V had largely been due to the influence of Marshal M.N Tukachevski;a dynamic and prgressive commander who became Chief of Staff of the Red Army in 1926. Thereafter there began a power struggle within the command (STAVKA), between him and the more traditional theorists. Tukachevski was a firm disciple of the emerging school who believed that mobility could be the most decisive factor on the modern battlefield. Consequently, the victory of his ideas within STAVKA signified the acceleration of a general increase of mechanization throughout the armed forces, which naturally led to the increased interest in," expansion of the airborne content.

However, this exciting pre-war development of the V.D.V was to be short-lived, and destined to take what proved to be an almost terminal path. During 1937 and '38 Stalin initiated the great purge of the Soviet officer corps, thus coming very near to destroying the very fibre of the armed forces," irrevocably perverting the development of what was the most advanced and inventive military apparatus in the world. This retrograde action did not stop until the High Command itself had been utterly decimated - only two of the original six Marshals surviving, Tukachevski being executed on the 11th June 1937. Thereafter interest in airborne warfare was lost, and all major development was discontinued.

The V.D.V administration,under Corbatov,was disbanded,and the top airborne commanders were either shot or simply disapeared. Although in 1938 German military intelligence still determined the Soviet airborne strength at around four brigades, this was largely misinterpreted. The brigades themselves were being allowed to retain their separate identity, but merely within the parameters of elite rifle formations.

For example,in 1939 the 212th parachute Brigade fought in a solely ground role against the Japanese in Mongolia. Participating in Zhukov's crushing victory at hhalkin Gol. While that September's occupation of eastern Poland saw the 201st, 204th and 214th parachute Brigades being similarly commited.

By 1940 the Soviet High Command seems to have gradually prepared itself to once again experiment with airborne warfare. Although attitudes were still highly sceptical, there was a definate realization that the moribund actions of the past few years had been detrimental to the ability of the Red Army to conduct a modern war. As a result of this change in attitude it was decided to try to break the deadlock of the 'Winter War' through the selective use of several fairly conservative parachute operations -- the first large-scale combat jump in history being made near Petsamo in November 1939. However, both this and a subsequent drop against the Mannerheim line were regarded as unproductive, and continued to reinforce the arguments of the pessimists in the Kremlin.

Consequently, the remainder of the three parachute brigades which had been assigned to the Finnish front continued to be engaged in their by now familiar ground role.

The Soviet annexation of Besserabia, in June 1940, also provided an opportunity for a limited airborne involvement,and on the 28th of that month both the 201st and 204th Brigades were airlifted in while the 214th constituted the reserve. Although it has since been disputed whether a paradrop was actually made, this event is still significant because it was the last time that the Tb-3 transport saw front-line service. Thereafter evidence indicates that they were replaced by the Ant-6 converted bombers, or the Li-2, which was a license-built or lend-lease version of the American DC-3.

USSR vs. Germany

As a response to the German success with airborne units in their early Blitzkrieg campaigns in the west and Balkans, the Soviets deceiaed to once again effect a U-turn vis-a-vis the V.D.V. The airborne component was expanded, so that by June 1941 the commander of the parachute forces Major V.Y.A Glazuhov and his chief of staff Miajor-General (Aviation) P.P Ionov, controlled the greater part of two complete airborne corps. Both of which were now largely based in the Ukraine. But, although on paper this force was the largest of it's kind in the world,this was a deceptive facade - because of the rapidity with which the brigades had been formed,the training of the parachutists was largely incomplete. For example,in the 4th corps only the men of the 9th Brigade had completed up-to two jumps;wnile the 8th and 214th Brigades were hardly airborne formations at all, with half of their men never having completed a single descent!

When the German juggernaut rolled over the Soviet border on the 22nd June 1941, STAVKA was forced to employ the V.D.V formations as infantry. The story of the Soviet near-collapse in the late summer and autumn of 1941 is well known. City after city falling to the mighty panzers, inexorably pushing along the seemingly endless dusty roads to the Soviet capital. The parachute brigades were unable to avoid these early cataclysms -- at least two of the 2nd corp's brigades being trapped in the great encirclement battles to the east of Kiev. While later that month the 5th corps was badly mauled in the ill-fated defense of Orel. Throughout these months several paradrops were attempted, however they invariably remained small-scale. For example, exceptionally hidden away in the records of Army Group North is a report for the let July which reads

"Near Koltiniani (40 kilometers southeast of Utena) at about 1800 hours, Russian paratroopers jump from seven aircraft (of which we shot down one)."

By December 1941 the Wehrmacht stood at the very gates of Moscow, their offensive power crippled by a combination of attrition and the appalling weather conditions. The time had at last come for Stalin to release his carefully hoarded Siberian reserves, to plunge into the flanks of their dormant opponent. The battle which was thus initiated turned out to be one of the most confusing and precipetous of the war. An ideal situation in which the V.D.V would have the long awaited opportunity to show it's true metal. Two separate paradrops involving Levashkov'e 4th corps were designed to penetrate Army Group Centre's rear areas, where they would link-up with local partisan brigades and the approaching Red Army ground forces.

On the 27th January 1942 the 8th Brigade jumped to the west of Vyazma, only to be quickly overrun and encircled. Then, just a few weeks later on the 17th Febuary, in a much more ambitious operation, elements of the 9th, 2nd and 14th Brigades were haphazardly thrown into a disordered melee near Yukhnov. They suffered the same fate as their previous comrades, but this time on a more wasteful and tragic scale. In late April that these paratroops, cut-off, out of supplies, and freezing in the inhospitable woods around Dorogobuzh, were finally and systematically pulverized by German air and artillery fire.

Stalin's first strategic offensive had lurched and stumbled to a premature halt. The first large-scale combat experiment with airborne troops had, for a variety of reasons been squandered. The 8th Brigades operation on the 27th January had been typical of how affairs had been conducted -- from the start it had been plagued by a lack of suitable aircraft -- only 39 out of the promised 65 eventually arriving. Those that did manage to then get off the ground dropping their passengers as much as 15 miles from their drop zones (D.Z). Only just over half of the 2,332 men finally forming into some semblance of a fighting unit.

Indeed, the coordination was so-bad that on the 29th,the deputy intelligence officer of the 4th Corps,Senior-Lieutenant Askenov,had to be flown into the D.Z in a tiny U-2 biplane. In order to actually find out what was happening -- radio contact having broken-down and Levashkov himself having been killed shortly after landing.

As a result of these failures in front of Moscow, throughout the summer and autumn months of 1942 the size of the V.D.V was considerably scaled-down from it's over-ambitious levels. The majority of these parachute formations then in existence were removed from toe reserve and formed into new Guards Rifle divisions. Under this guise they went on to earn honours during the 1942/43 winter campains. particularly those around Stalingrad, where the 39th Guards Rifle Division (ex-5th Parachute Corps) heroically fought to destruction in the 'Red October Plant'. Similarly, the majority of those airborne formations who had been fortunate enough to retain their identity were also committed in a ground role - the 20th Guards Airlanding Corps participated in the decisive July/August 1943 battles around Kursk under the control of the 4th Guards Combined Army).

While the January/February 1944 battle for the Korsun pocket witnessed the massive commitment of the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 6th and 7th Guards Airborne Divisions.

Although the failures of the winter campaign was still fresh in the minds of the members of the high command,they never felt self-confident enough to completely abandon all hope for a spectacular and decisive mass-paradrop. Consequently, they continued to dabble with a series of small specific airborne operations, of company size or less. At the same time retaining up-to a full Guards airborne corps in reserve. During the Caucasa campaign of early 1943, the 90th Special Landing Regiment ( a veteran outfit consisting of seven parachute trained companies of marines) was successfully dropped on Maikop.

Then on the 4th of Febuary it provided two companies for the combined airborne/amphibious attack on Novorrossisk - parachuting straight into action and eventual destruction around the village of Vasilevka.

Kanev

In September 1943 the STAVKA was at last provided with an ideal opportunity for an ambitious airborne operation involving all five brigades of Kapotkin's reserve (1st Airborne Corps - Major-General Zatevakhin). If they could grab a crucial bend in the Dneiper near the small town of Kanev, they stood a very good chance of trapping the retreating German 24th Panzer Corps on the wrong side of the river. Indeed, if they could get enough troops across they might even be able to smash through to Kiev, and thus encircle the entire 4th Panzer Army.

The Soviet High Command thus initiated an operation which, in both size and strategic value,would have eclipsed even Arnhem if successful. The rewards were truely enormous, however the success of the whole operation hinged on whether the paratroops and their supporting gliderborne battalions could be landed safely and precisely before the enemy were able to reinforce the defense.

From the very start of the exercise Zatevakhin's men encountered similar problems to those which had undermined their efforts during the winter of 1941/42. Originally it had been hoped that all three of his parachute brigades would be able to land simultaneously, but because of delays in concentrating the units at their forward airstrips, this had to be dramatically changed right at the last moment. Also, whereas it had been planned to land on the night of the 23rd, the atrocious weather on that day caused cancellation until there was a suitable break -- on the 23rd only six of the two hundred plus aircraft turned-up at the airstrips!

On the afternoon of the 24th STAVKA deceided that the conditions had improved enough to go-ahead that night. They had finally managed to sort out the administrative tangle and assemble the required amount of planes. The A.D.D had found a mixed group of around 50 Ps-84 bomber transports, and 150 Il-4 and B-25 night bombers; while the airborne airforce had assigned a further 13 Il-4s for dropping support weapons,a squadron of Po-2 spotter planes, 10 glider tugs,and a combination of 37 A-7 and G-11 gliders. Finally, Lt-Ceneral Krasovsky's 2nd Air Army was now in position to provide maximum fighter cover.

Despite the impressive collection of airpower, the paratroops began to encounter difficulties almost as soon as their transports began to arrive at the advance airstrips. 'Whereas it had been assumed that each plane would have no problems in carrying at least 20 men, when they landed it was found that they were only large enough for 15-18 men. It was also found that there was still inadequate numbers of aircraft to carry both brigades in a single drop, and that those which were arriving were still coming in late because of the bad weather. When the planes finally landed they then ran into refuelling difficulties ; at Bobodukhov airfield it was suddenly realized that there was not enough fuel for the awaiting machines. On the 5th Brigade's allocated airstrips there was the ludicrously small force of just four tankers!

Faced with these problems the commanders on the spot were forced to resort to desperate measures, such as loading their men onto any motor vehicle and trundling them around the widely separated airfields, in the middle of the night, looking for spare aircraft and fuel.

While this was happening throughout the Ukraine, those planes which had been able to become airborne were usually split-up from the rest and forced to straggle into the D.Zs either individually or in small groups of just a few. The most chaotic situation was at the 5th Brigade's airstrips. Here only 48 transports eventually turned-upland hardly any were able to then form into a combined formation. The 3rd Brigade was considerably more fortunate,with the bulk of it's required planes arriving in good-time, refuelling, and forming-up on schedule - a total of 296 sorties dropping 4,575 men.

The attempted paradrop at Kanev had become a confused tangle even before the men had reached the battlefield, from now on the situation was to become a nightmare. The delay of just one day had been enough for the Germans to significantly reinforce their positions around the bridgehead - both the 3rd and 5th Brigades landing directly on the concentration areas of the 19th Panzer Division and the 10th Panzergrenadier Division. The whole exercise was rapidly becoming a bloody disaster of the worst magnitude. Absurdly, the 5th Brigade missed it's intended D.Z by more than 20 miles, while in the 3rd brigade's D.Z were counted 692 dead and 209 prisoners. The largest single concentration of paratroops to be organized once landed was an ad-hoc group of around 150 men under the immediate direction of the commander of the 5th Brigade. But even this unit was quickly annihilated before it could move-off.

Eventually the survivors of the Kanev landings managed to group themselves together in the forests between Kanev and Cherkassy. Here some 2,300 men were joined by local partisans,and later went on to serve as a joint brigade-group during the winter battles around Korsun.

Not surprisingly, the Soviets were not slow to comprehend the magnitude of their disaster. Thereafter for the rest of the war, all large-scale airborne landings were abandoned. The V.D.V and it's masters had become beset by an inferiority complex which persisted until as late as the mid-1950s. Indeed, the scandal of what happened at Kanev has continued to be such an embarrassment that there is not a single mention of it in either the official 'History Of The Great Fatherland War',or the many subsequent standard works by Soviet historians. The largest and most amoitious Soviet airborne operation of alltime has been conviniently and quietly forgotten.

For the remainder of the war the V.D.V was effectively censured of all designs on parachute operations. But this did not mean that air-transport was also to be abandoned, and during the first week of October 1944 the 5th Long Range Air-Transport corps airlifted in the 700 men and 104 tons of equipment of the 2nd Czech Parachute Brigade (a pro-Soviet unit formed in the U.S.S.R. during January 1944), to the assistance of Slovak insurgents. Eventually over 1850 men were landed to assist the rebels, after an advance group of just 12 men had parachuted in on the 17th September. The last campaign involving the V.D.V during the war was that against the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria and Korea.

On the 19th August 1945 a special assault force of 225 were flown in to Mukden aerodrome as part of the disarming process. While another group was similarly landed at Changchun. Thus ended the V.D.V's involvement in World War Two, however the legacy of Kanev was to last well into the future.

It not being until the late-195Os that any significant new developments were made. Since then the U.S.S.R has once again effected a change in policy,and the V.D.V is back in favour. At the present it's airborne capability stands at around seven full divisions and a miscellaneous number of smaller units. The wheel has come full-circle, with the V.D.V once more retaining it's rightful place as the world's largest airborne force. It is unlikely to be robbed of it's crown for a second time!

WARGAMING SUGGESTIONS

Wargames with Soviet paratroops can be an exciting and yet unusual topic. Particularly rewarding will be small unit actions of company size or less. While larger battles can be just as easily fought using rules such as the W.R.G 'Armour and Infantry 1925-50',which have a section covering airborne landings. If you attempt to incorporate the mechanics of a landing itself you will have to be careful to recreate the inordinate amount of confusion - Soviet paratroops had a nasty habit of being scattered as much as fifteen miles from their intended D.Z, after being dropped from altitudes over 2000 meters apart! Those who did manage to land within the proximity were often injured on landing, and those who were alright took a considerable amount of time to assemble into some kind of fighting formation. The Soviets placed a lot of stress on the leadership of officers at the expense of the initiative of the NCOs and the lower ranks.

This meant that those in charge often failed to acquaint their men of the situation,and that when they were separated on landing all but a few were completely in the dark. Wargamers must thus be especially aware of the strong chance that their scattered groups of men will probably be operating unawares of both their own and their comrade's positions.

Consequently, the only chance of these groups forming-up was when they ran into each other by accident. Whereas in most armies the standard practise for rallying upon landing was the use of prearranged rendezvous points (R.Vs),it is needless to say that this proved to be quite unworkable for the V.D.V! Also if you try to refight Kanev you should note that the operation was carried out in the early evening, and that the later planes arrived over the D.Zs in total darkness. Thus making the task of forming-up almost impossible.

As for weaponry the Soviet paratroops were usually equipped with just their own personal s.m.gs, which were considerably more common than rifles. Although the V.D.V had pioneered air-transporting heavy weapons and tanks, either by dropping them on special sleds, or strapping them to the underbelly of a transport aircraft (this last method was apparently used to good effect in the occupation of Besserabia in I940),in all their combat operations they invariably failed to land even light support weapons.

For example, during the Kanev operation the 3rd Guards Airborne Brigade possessed 16 45mm anti-tank guns,yet not one managed to reach the troops on the ground. However, within the prisoners the Germans took on their D.Z were the brigade librarian, band leader, and a team of women nurses. All of whom were strikingly well equipped! There was no attempt to develop specialist weapons containers, and a favourite Soviet technique was to merely place the heavy machine-guns or mortars in a canvas bag to which would then be attached a parachute. The majority of which were either lost or damaged upon landing. Although the V.D.V had a large glider force (at Kanev there was a total of eight battalions organized into the 2nd and 4th Guards airlanding Brigades), these were never able to make a successful landing because the D.Zs were invariably overrun before they could be committed.

So-far you might be excused for thinking that wargames involving Soviet paradrops are a bit one-sided. If you don't want to fight small-scale skirmishes you will probably have to introduce other Soviet non-airborne troops for the sake of game playability. In both the operations in front of Moscow, and that at Kanev, the paratroops were landed either amongst or close to units of the Red Army -- at Yukhnov the 4th corps formed a joint force which included Red Army infantry, armour, cavalry, and even partisans.

While at Kanev the D.Zs were easily within range of the heavy-artillery of Voronezh Front, and within striking distance of the T-34s of General Rybalko's 3rd Guards Army. Consequently, wargamers will find it necessary to integrate their paratroops with other units,however they should be careful not to over-emphasize their ability to co-ordinate their movements. Soviet inter-service communications were all-too-frequently non-existant.

Finally a few words about victory conditions and objectives. Except for some of the small-scale parachute operations, they were usually defensive orientated - either to reinforce an existing position or seize a position which could be quickly relieved. The Kanev operation was just such a defensive plan, with it being intended for the paradrop to merely enlarge the 3rd Guard's bridgehead. The fact that the D.Zs ended-up behind the German lines was more a matter of bad luck caused by the delay in time, than daredevil ambition. Wargamers should thus try to land their paratroops just ahead of their own lines - while they try to hold on to a territorial objective such as a hill or bridge,a relief force should try to rush through to their immediate relief. As wargamers will probably find out,the V.D.V is much too brittle a force to attempt something as extended as Arnhem.

Conversion of Airborne Forces to Guards Rifle Divisions - 1942

May-42: 2nd airborne corps formed (32 guards rifle Division)

July-42: 3rd airborne (33 guards rifle division-grd); 4th airborne (38 grd); 6th airborne (40 grd); 9th airborne (36 grd); 10th airborne (41 grd); 1st airborne (37 grd).

August-42 5th airborne (30 grd); 7th airborne (34 grd); 8th Airborne (35 grd).

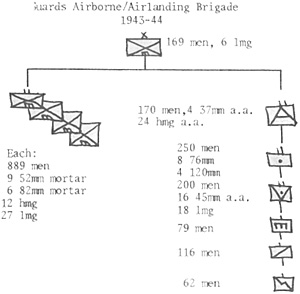

Guards Airborne/Airlanding Brigade: 169 men, 6 lmg

Bibliography

A. Boyd, The Soviet Airforce, London, 1977.

P. Carell, Scorched Earth: Hitter's War on Russia. London.

J. Erickson, The Road to Stalingrad: Stalin's War with Germany, Vol. 1. London, 1967.

J. Erickson, The Road to Stalingrad: Stalin's War with

Germany, Vol. 2,-London-,_ 1985.

Larionov, Yeronin, Sobvyov, and Timokhovich, World War Two: Decisive Battles of the Soviet Army, Moscow, 1984.

N.V. Madej, Red Army Order of Battle, 1941-43, Altentown, Penn, 1983.

J. Prados, Kanev: Parachutes Across the Dneiper, Oakland, CA., 1981.

S.M. Shtemenko, The Soviet General Staff at War, Moscow, 1975.

J. Weeks, The Airborne Soldier, Poole, Dorset, 1985.

Zaloga and Loop, Soviet Bloc Elite Forces, London, 1985.

Back to MWAN # 25 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com