"The object of any wargame (historical or otherwise) is to enable the player to recreate a specific event and, more importantly, to be able to explore what might have been if the player decides to do things differently."

- --Jim Dunnigan, Chapter 1, "What is a Wargame?" The Complete Wargame Handbook, 1980, 1993, and 2000

"Simulation is the imitation of the operation of a real-world process or system over time ... Simulation is used to describe and analyze the behavior of a system, ask what-if questions about the real system. Both existing and conceptual systems can be modeled with simulation."

- --Jerry Banks, Engineer, Introduction, Handbook of Simulation, page 3-4, 1998

Historical wargames have always been designed to recreate something of warfare, past or present. But that's what simulations do too- imitate some real-world process or event. Many gamers today get nervous with this comparison, because simulations seem to be something too serious, too scientific, too complex for a hobby. It doesn't matter whether you call them wargames or simulations, if they're both designed to do the same thing, simulate history in some fashion, then they are the same thing. A rose by any other name .... Because this is true, the concepts, design philosophies, and methodologies developed by professional simulators can shed some light on the mysterious and often misunderstood process of designing a simulation. In comparison, some of the beliefs circulating in the hobby are self-defeating and unworkable.

SIMULATIONS AS ENTERTAINMENT

For instance, there is a belief, that unlike wargames, simulations aren't designed for entertainment. They're only for serious stuff like military training or scientific research. Nothing could be further from the truth. Outside of wargaming, many simulations are designed for fun. Millions of dollars a year are spent on simulations as entertainment. Grand Prix video games, educational games, training games, computer flight simulators, and many business games, to name just a few, are all designed to entertain.

Of course, the reverse is true. Many of the wargames designed for fun since the 1970s have been and are now being used by the military-and such things as paint ball competitions and the Avalon Hill board game Fire Fight were first developed by the military. Any number of computer games had their program beginnings in some simulation design used in research. It doesn't matter how you define fun, because it doesn't define what a game or a simulation is, should be, or can be.

Then there are some simulations that end up being entertaining, even when that wasn't the designer's intention. The granddaddy of them all, Kriegsspiel, had a serious goal: to train Prussian officers, not to provide a fun time. Yet the designer, Captain von Reisswitz, admitted, to his surprise, that his design was entertaining. Every wargame today uses many of the same mechanics pioneered in the 1824 design, from combat charts and phased turns, to die rolls. A good number of gamers still play Kriegsspiel-for fun. [The Kriegsspiel Society offers the original 1824 rules at http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/kriegsspiel] Fun isn't the dividing line between games and simulations-it's only a way of describing the playing experience of both.

SIMULATION OR GAME?

I enjoy flight computer simulators and play them often. Are they games or simulations? They're designed as both. I now fly real sail planes and am working on my license. The first time I flew a sail plane, my instructor knew I'd had some kind of previous experience because I did better than expected. Now, I'll be the first one to admit that a flight simulator has nothing on the real experience of flying a sail plane. The simulators I played were for powered craft, not gliders. Even so, while the computer model was very "far removed" from the real experience, it HAD simulated what the game designer had attempted to recreate for funsome of the flight characteristics of airplanes in relation to gravity, speed, and the ground. And the simulation did it with enough validity that I demonstrated a number of skills when I piloted a real plane for the first time.

If I'd had fans blowing air past my computer room window at 60 MPH and been seat-belted to my chair while playing the flight simulator, that would not have been a `better' simulation of flying or `closer to the real thing'-nor would I have flown the sail plane better because of it. Of course, those little touches might have `felt' more realistic, but that totally subjective conclusion wouldn't have meant a thing in regards to the effectiveness of the flight simulation. In fact the added complexity could have interfered with what was being simulated.

The computer program `worked' as a simulation because of what reality it focused on, not how much. It also worked as a game because that focus kept the complexity manageable-That, and the fact a good deal of reality can be challenging and fun, particularly when you don't have to worry about crashing your plane.

Historical wargames are usually attempts at simulating something of history. Both wargames and historical simulations are designed to recreate a part of the past, some a little bit, some a lot. Unless the designer specifically states that his design has no intention of accurately capturing anything of the past in game play, the similarities can not be avoided, and gamers have every right to expect the same level of recreation from both. [Pun intended.

HOW DO SIMULATIONS WORK?

The first `given' in simulation design is that there are an infinite number of mental, emotional, and physical components to reality. A simulation can only capture a few of them, regardless of it's size or complexity or kind of design. A designer is limited in what he can simulate and has to decide what he is going to specifically model. This means that three designers can simulate the same event, and all chose very different elements of reality to simulate, ending up with very different designs-of the same event.

The goal of the design dictates what parts of reality should be imitated. No simulation can do it all. That is why, for instance, the army has hundreds of simulations, all for training infantrymen for battle. For instance, here are three current simulations designed to train soldiers for combat.

- 1. Obstacle Course. An old regular, the `live' obstacle course includes barbed wire over a mud pit where soldiers have to crawl while a machine gun fires lethal ammo over their heads. This simulation is fairly visceral in its intent, the goal being to accustom soldiers to operating `under' live fire.

2. Computer Program. A computer program presents movies of terrain and troop movements from the ground and then asks questions of the participants about what they see and would do. This trains soldiers in situational analysis.

3. 'Laser-Tag' Exercise. An umpired simulation of urban combat tactics, squads of soldiers defend and attack houses and city blocks using guns that fire blanks and use a laser light to `hit' enemy soldiers. The goal of this simulation is to practice squad tactics with live opposition.

Now, which one is closer to reality, which is a `better' simulation? Which is more `realistic?' Just because the soldiers in one are physically on their bellies in the mud with real bullets flying overhead doesn't make it `closer to reality' than the computer program or the laser-tag exercise. They all simulate different parts of the reality called combat; they all have different goals. Yet, considering the number of things they don't simulate, all three fall very short of recreating `the real thing.'

What is important is that they all address very real aspects of modem combat. What's in the simulation that far more important than what's left out-what's in a simulation is what determines its quality and usefulness. All three training designs above could be equally accurate and effective simulations if they model what they were designed to model. Yet, all three simulations aren't even close to recreating real combat.

CHEAP SHOTS

About here is where the critics of simulations and the defenders of reality come out of the woodwork. The wargamer points out that battle demands a lot more of a soldier than crawling under barbwire. The well-read expert on modem combat will point out that no engagement has enemy troops conveniently staging troop movements for analysis. And the staff sergeant who fought in Desert Storm sagely observes that in real combat, there are no umpires and when you get shot, you die.

It's all true. Each simulation misses a lot of reality. The Obstacle course asks for no combat decisions from the soldiers. They know they're not really being targeted. There are no enemy soldiers to maneuver against, and they aren't firing their weapons etc. etc. etc. In fact, there is a whole boatload of combat experiences the obstacle course fails to address that are simulated in the second example, even though the participant is sitting on his butt in an air-conditioned room pushing buttons. Here soldiers are being asked to analyze terrain and troop movements and come to conclusions about what is happening and what should be doneimportant skills for a combat infantryman, but light years away from real combat.

The third simulation asks for tactical decisions `in process' against an opponent, something the first two do not do. However, unlike the obstacle course, there is no live ammo-everyone knows that no one can get hurt. A number of behaviors are required of soldiers, or are banned, for safety reasons that have nothing to do with real combat. There is an umpire. And all the soldiers know when the exercise is over and the limits of the combat area. Unlike the second simulation, terrain analysis and many tactical decisions are already made for the participants. The number of opponents is generally known so such analysis is unnecessary. There are no artillery strikes, tanks, RPGs etc. other squads and/or companies to coordinate with in the exercises. NONE of the simulations come anywhere near to what real combat is like, but each captures aspects of it, and that is what they target in training. One officer in the Iraqi War mentioned this exercise, saying he was glad his men received the training. He said that it made a difference, but that his soldiers still had a great deal to learn when they entered real combat.

However, even though this is all true, the critics are still taking cheap shots. Not only is it very, very easy to point out what a simulation is not capturing of reality, the critics are faulting the designs for things they were never designed to simulate. Each simulation was designed for completely different purposes, and simulate only a small fraction of real combat. The only thing the critics see is the big portion of reality not addressed. Any yahoo can see that. What should be examined, what constitutes a simulation's true value and `accuracy' depends on how well the design simulated its few, selected elements of ground combat-not how much reality was purposely left out of the process.

SOME IMPORTANT POINTS

SOME IMPORTANT POINTS

1. Fun. While none of the above simulations were designed to be `fun', many soldiers report the last two as `fun to play' and a few even think the first was `fun' if the mud is deep enough. Fun is a quality that doesn't abide by categories.

2. Why not one simulation? Why didn't the Army take those three simulations and create one, big, more realistic design? It certainly looks like it would be far more efficient. They didn't because:

- A. It would be too complex. It would be so complicated that it would take far too many resources and man-hours to make it work, assuming that the designers could actually make such a monster function at all.

B. Many of the very things that were `accurate' in the individual training designs would be lost if such a mega-exercise was created,

C. The actual simulation experience would be tainted. Try and put too much in and it changes what the exercise is about. Like one gamer recently admitted, "I've stayed away from Napoleonic games in the past because playing them was too much like doing my taxes."

D. The amount of time, money and effort would be trebled. From a training standpoint, trying to train three separate sets of skills in one simulation would lessen the impact of the training, requiring that soldiers carry out a very expensive training three times as often to learn everything.

3. The other parts of the simulation: Also note that like all simulations, the three examples above have procedures and mechanics in them that have absolutely nothing to do with recreating modern combat. For instance, in the laser-tag exercise, You have umpires, the buildings fought over have no glass in the windows and little furniture. The soldiers are burdened with `unrealistic' laser equipment, both sensors on their body and on the barrel of their guns-very unrealistic-yet they're necessary to make the simulation work. The `unrealistic' elements support the design without being part of the simulated reality itself. One of the reasons why it is vital to have clear simulation goals in place.

In the MWAN #130 article, "Wargame Design is An Art, not a Science", the luckless simulation designer, Winston Wargamer, doesn't understand this. He believes that every rule and mechanic must match some aspect of his research data, otherwise it isn't a simulation. This simulation `rule' is explained thus:

"No, you see, Winston is designing a Simulation, not a game. You can't just make-believe when you design a simulation. Things have to be based firmly in fact. That means that-just as in the real world-certain things happen in a certain order, ..." p.79

So he unquestioningly believes if he has the data right, the rules will automatically work. And predictably he runs headlong into this simulation misconception. He says, "I know I've got the data right," but his movement rules don't reflect it, so he concludes, "I must be doing something wrong." He is. He is trying to build a simulation without understanding the structure and dynamics of one. He also defines game design as `make-believe' in comparison to simulation design,. even though the two obviously use the same concepts and structures in their design. Professional simulation designers would call Winston's belief absolute nonsense. Certainly the consequences are.

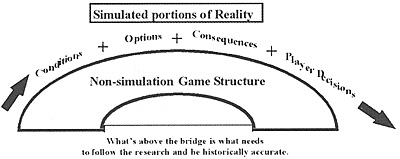

Predictably, he has to ignore the data simply to move forward in his design effort. And thus, "without even seeing himself doing it, Winston commits his first fudgy rationalization." Because he doesn't know how to structure a simulation, he unconsciously acts-and of course, winds up in unexpected places. A simulation recreates a few parts of reality, usually in the form of simulated conditions and options, and consequences surrounding the player's decisions-decisions that mimic those required in the real world-and only the parts the designer has chosen. Perhaps a graphic will help show the structure of a simulation, there is a unrealistic [make-believe?] structure to simulations that act like a bridge, allowing what is being simulated to play out from beginning to end.

Winston, poor shmuck, believes that a computer simulation can be created without an 'unrealistic' computer or written code, and a simulation game can be designed without 'unrealistic' game mechanics. It screws up everything he attempts. And without any knowledge of simulation design, a methodology, or concrete simulation goals, what tools can he possibly use to design his simulation? He has nothing to go on but what "feels right." And of course, this makes for one unhappy simulation designer.

Winston is the aircraft designer who is ignorant of aerodynamics and plane construction techniques, so he keeps crashing his design until it `feels right' and flies-for a while, sort of, in someone's opinion. And not surprisingly, the test pilots aren't very enthusiastic about flying his designs.

4. Where's the reality? If you asked the soldiers where the `realism' was in each training design, they would be able to list for you exactly what battlefield conditions are being simulated and what conditions aren't. I can do this with the flight simulator. And why can we all do this? The designers told us-in fact emphasized it. The soldiers and I have been informed of the specific simulation goals for each design, and we were informed about what decisions and skills we were practicing that corresponded to `the real thing.' This isn't magic or some very difficult behavior on the part of the designers. The soldiers got the information verbally from army instructors, while I read it in the instruction manual for the computer game.

Informing the participants of the specific simulation goals is part of effective simulation design. A design is much more valuable as a simulation when the players know exactly what parts of reality are being recreated for them. Unfortunately, wargame designers are really vague on this point for the most part, which not only detracts from the design's effectiveness, but leaves wargamers to constantly debate what is actually being represented-usually to absolutely no conclusion.

5. How many ways? Each of the combat training simulations targeted goals that could have been, and often are, simulated in very different ways. It is possible that every of a hundred different designs could accurately imitate the very same selected portion of reality and never share the same components. This leads us to Sam Mustafa's question in MWAN #127. Considering his beliefs about simulations, it is a reasonable one:

"Now if wargames are simulations - if such a thing is possible - then how do you account for all the different ways to represent this one battle?

And how do you account for the fact that Joe really likes this Bulge game but not that one, and Steve really likes that one, but not the other.... They're all the same scale: all divisionlevel representations. They all cover exactly the same order of battle, map, and period of time."

So here is the answer: Each designer has chosen to simulate different aspects of the Battle of the Bulge with different game mechanics. Even if they all have the scale, map, OOB, and time period, that is not the game content, just the boundaries. The game process and game mechanics are what makes the game and the simulation-which is why Joe and Steve can like different games even when they share the same division-level representation. It's not the scale of a simulation or game that counts, but the unique quality of it's play and what it simulates.

The actual game mechanics can be very different- and obviously are or the designers would not have had any reason to create a Bulge game identical to the last one in the same scale.. There are an infinite number of aspects to the actual battle and an infinite number of ways to represent them in a simulation. And if done right, they can all be equally `accurate' and simulate `The Battle of the Bulge." There is no single `true simulation' of any one event, though that is what the question seems to suggest.

To actually attempt creating `the one true simulation', the design would have to recreate the entire battle, the blood, steel, and explosions down to the smallest detail, from start to finish. Not only is it impossible, but who would want to? My question is how is it possible for wargames and simulations to not be the same thing? Designers continually state identical goals for both.

THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GAMES AND SIMULATIONS

Professional simulation designers have thought long and hard about what it is they are doing. When they create a simulation, they are creating a functioning model, a process to be played. To do that, they need to be able to describe the individual parts of the model.

Please remember, even though the designers work in very diverse fields, such as the medical sciences, weather and geology, business and management, architecture, crowd control, computer programming, entertainment, law enforcement, the military, scientific research, engineering, and politics, they realized that they all worked with the same basic building blocks of design.

They knew if they were to create simulation models, they needed to under stand the parts. So, they simplified. One thing they realized is this: There are only four components to any game or simulation-What the simulation community calls "Modeling Structures": Time, Activities within the passage of time, Events, caused by the activities, and Decisions which determine the activities. The `environment' is simply the set of conditions that may or may not modify those elements of design. If the environment becomes an active participant, like animal attacks, rain or an earthquake, then that is considered an Event for design purposes.

In turn, these four building blocks of simulations are then seen as the only four ways the process of play or action in a simulation can be regulated, whether that design is a computer model of viral infection, a training exercise for sales people, or a military wargame, etc. etc.

The four building blocks of simulation design also have corresponding methods of regulating the passage of time in a design-which apply to wargames. This simple reduction of design complexity helps designers analyze what it is they are attempting to do. It is a tool, an effective set of concepts that help designers. It is not the only way to consider simulation design, or some mythical design "Truth." But the tools have been used over decades in a variety of design with success. And obviously, many designers then go and combine the various components in different ways, but now what is being done is much clearer.

Any game process is identified as in one of four components -or combinations of these four "Modeling Structures." In controlling the flow of time/game progress, one or more of these components are used.

1. Units of Time: This is the game turn, whether exact times are indicated [like ten minute turns], or simply units of time [five turns represents a day in the game] Most all wargames like Armati, Fire and Fury, Command Decision, use this as the way to illustrate progress in a game design. Of course, being a separate community from wargame design, the concepts are given very different names. For instance, regulating play/simulation processes with time is referred to as "Activity Scanning" where activities are monitored at fixed time intervals-i.e. turns. Of course, some of the terms are counter-intuitive for wargamers. [I have put the generic simulation terms in parenthesis.]

2. Units of Activities: [Process-Interaction Method] A set number of activities occur to indicate the passage of time, Like Chess: one move per `turn.' The Sword and The Flame and a number of others use this process. In most cases, cards represent when and what kinds of activities can occur in a turn. Many combine Units of time and activities, so as an example, Games like The board game For the People or Piquet, have so many cards or activities allowed in an hour or other period of time. Some like BattleCry, make the activities the sole arbitrator of game progress. Others like Jim Arnold's Leadership rules or Sam Mustafa's Grande Armee use Command Points to represent the kinds and limits of activities within a turn.

A great deal of adjustments can be employed with the activities. A particular commander can have more or less activities per turn to indicate his quality as a leader. Or the cards or command points can be limited to represent a particular army organization or in the case of ACW boardgame For the People, the ability of an entire nation to wage war four cards per season in April of 1861 and seven by 1863.

3. Units of Events: [Event-Scheduling Method] In this form, time moves forward until the next event occurs, requiring decisions and activities. Of course, the conclusion of the all the activities provoked by the event ends a turn or unit of game play.

This is George Jeffery's Variable Length Bound or VLB system. He didn't ever get it into a playable form, but a number of ideas have come out of it, including Grand Piquet's movement from `horizon' to `horizon,' which is itself a combination of #2 and #3-movement can go forward until the next `event,' terrain or enemy proximity, requires an end to a unit's current movement.

4. Units of Decisions: [The Three-Phase Method.] This one has never been seen in gaming circles and holds some interesting possibilities. The amount of time that passes is determined the players themselves. For example, a player chooses how long his next move will be, whether in minutes, hours or turns. Combined with #2, The player might determine how many activities he will perform within a turn. The opposing player could be allowed to respond based on #1-#4. For instance, he could either be forced to take the hour turn too, because of the moving player's initiative, or he could be given the ability to stop the forward motion of time at a certain point to react, say 10, 20 or 30 minutes into the moving player's move.

The distance issues for pre-radio games, where there is a communication time-lapse between a command decision and its execution could be simulated this way. A player sends out orders that cover an hour, but if the opposing player interrupts that, any reaction on both his part and the moving player could only be from a `half hour radius' of units. It would also be a way to move games along through what are necessary but very boring points in the play in the approach phase.

Of course, this same set of four building blocks can be used to end the `turn' or the entire game or simulation:

- 1. A set time limit or variable time limit. This can be 8 hours, 5 turns, one year, either a fixed time or variable, based on a die roll. Games like Piquet, Spearhead, and Volley & Bayonet generally have battle scenarios that have time limits, usually the end of the day.

2. A variable limit based on activities. When a set number of activities are used up the game is over, or when an particular activity is carried out by either player. This one isn't often used.

3. An event like Checkmate or sundown, or the capture of an objective. Many games have either events or chance shortening or lengthening the number of actual turns. Grande Armee is among a long line of games to do that. Even as early as SPI in the 1970s, there were games designed where chits numbered 0-5 were put in a cup and one was drawn a turn. When the number of chits added up to twenty, the game was over. Others had events within the game add or subtract turns if they occurred. As an example, For the People has the game end if Lincoln isn't re-elected in 1864, or if the South games twice the Strategic Will points compared with the North.

4. Player decision-one or both decide to end the game. Some games like Monopoly have no set time limit. Monopoly had no victory conditions. It is ended by player decision.

These building blocks are nothing but tools that help the designer create clarity in game/simulation design. For instance, it is easy to see how simultaneous movement continually had problems: In its pure form, it was an absence of all four of the design building blocks. Lots of stuff just happened with all players moving at once without any internal regulation of time, or game activities or significant events or player decisions. This led game designersd to create mini-turns within the simultaneous movement phase in an effort to direct game activity. The solutions were, not surprisingly, based on Time, Activities, Trigger Events or player Decisions. Thus you have `reaction phases', `opportunity firing', `counter charges', etc. all using one or more of the four building blocks of simulation design.

UNIVERSAL GUIDES

What is surprising is that all these universal design concepts were developed by simulation designers from a very diverse range of fields--completely separate from wargame designers. Yet, they are talking about the very same issues as wargame designers, and coming up with some extremely applicable concepts and methodology. They have been in place and used constantly since the late 1970's with only minor refinements. Why?-because they work. They function very successfully as design tools.

The building block concepts I related is just a small sample from a distillation of four decades of experience in creating simulations in dozens of fields by thousands of simulation designers. A single wargame designer can boast of how many designs? One, two, or perhaps a dozen if really active- dozens if you are a Frank Chadwick or James Dunnigan. Since SPI, game designers haven't done any `distillation' of their working methods. It's still pretty much by `feel', yours being different than mine.

The professional simulation community may not know everything that hobby designers do, but you can be certain that hobby designers don't know much about what the professionals have done. Most of it can be very useful, and a good deal of it addresses issues that wargame designers have been struggling with since the 1970's.

NOT REQUIREMENTS

Do wargame/simulation designers in the hobby have to use these simulation concepts. Of course not. But if they work, making the design process more efficient and effective-if they clarify dozens issues in game design and representing history, why wouldn't they?

Sure, there are folks who learn to operate their computers without any ever looking at the instructions or listening to others with experience. It's their choice. They like the trial and error method. But why bother with such a painful process, if Winston Wargamer is any example, when it isn't necessary, and when it can often perpetuate those errors. Simulation design is tough enough as it is.

In the next and last part of this series, I will show that all experienced simulation and game designers sooner or later develop similar, specific methodologies in designing simulations and wargames. We will explore how to create a simulation game following these guidelines from the simulation community, the methodology developed by a wide variety of game and simulation designers. It is how accurate simulations are produced; it is how the reality is put into the design, whether historical in nature or not-and the methodology can help create fun games.

Back to MWAN # 133 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Legio X

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com