WARFARE: PEOPLE AND TOOLS

Warfare is a contest of wills between peoples armed and equipped with the tools of war. The capabilities and effects of these tools - from hand-thrown rocks to satellite-guided smart munitions - can be represented in miniatures rules to match closely empirical results and real-world experience through relatively simple game mechanics. The behavior of the people employing these tools against each other is not quite so easily modeled and is therefore often neglected in rules and scenario designs. Many game designers engineer some aspects of battlefield psychology into their rules, particularly at the tactical (or unit) level. Few provide game mechanics that model the psychology of the overall army, or that of the battlefield commander as represented by the player. If our miniatures game rules do not provide for psychological reactions at the army or command (player) level to significant events, or developments, before or during a battle, an important aspect of warfare has been lost. Moreover, the rules should provide the incentive to generate those events and reactions and use them as a weapon against our opponent.

In recent years, the rapid, violent, and conclusive manipulation of the resolve of the enemy through movement and firepower has been developed into a doctrine known as "maneuver warfare." While not as tangible as the spear, the tank, or the stealth bomber, maneuver warfare is as much a tool of warfighting as are any of those weapons. To omit maneuver warfare from our gaming, especially in campaigns and battles in which it historically played a crucial role, denies us an element of realism, historical insight, and the opportunity to experience "what it was really like" for which we strive so earnestly. In this article I will describe the concept of maneuver warfare and propose some ideas on how those concepts can be incorporated into new or existing rules and in scenario design.

WARFARE: PSYCHOLOGY AND PHYSICS

Warfare is a violent blend of psychology and physics. As an example, imagine a column of soldiers stopped on a road. If fired upon by a heavy machine gun, the casualties suffered over time, if the soldiers were to remain standing in place on the road, can be calculated based on the rate of fire and the known effects of the HMG on the human body. Assuming that the soldiers are static and that the gun has unlimited ammunition (and enough spare barrels!), it is only a matter of time before every soldier is grievously wounded or killed and their unit becomes ineffective for further combat. (If this example sounds too contrived to be of any value, then you may be interested in reading Chapter 2. The Effects of Weapons, in NUMBERS, PREDICTION, AND WAR by Col. T.N. Dupuy, US Army, Ret.)

Fortunately, in a real-world situation, this horrific calculus is unlikely to occur. Even if their training or simple logic fails them, the human instinct for survival would take over and the soldiers would scramble off the road, seeking shelter behind any available cover.

In our miniatures gaming we would never be satisfied with rules that let a machine gun progressively destroy a column of soldiers without allowing, or even forcing, the defending soldiers to react by retreating or taking cover. Yet, if we scale this tactical example up, the rules we use to play games representing battles between armies do exactly that. Few rules model the psychology of the commander at the battlefield, operational or strategic levels. We pit entire armies against each other without any provision for the collective response of those armies or their commander to either events that occur on the battlefield, or to conditions that have developed at a higher (operational or strategic) level of the conflict. We accept rules that model morale or other psychological factors at the small unit level, but we often balk at rules that "artificially" constrain our actions or options as players. This is fallacious. As players we are quite capable of physically moving a figure or model from one end of the game table to the other, but we are constrained by, and cheerfully follow, rules that limit the movement of that figure or model based upon the "real" movement rates of the unit it represents. Rules always "artificially" restrict our behavior in an attempt to model the "real" world - that is what rules are for!

The maneuver warfare game must impose additional restrictions on players in order to model successfully the psychology of command. This should be no less natural to us than rules that restrict movement, or ranges of weapons, or things like whether or not your 18th Century army can be armed with charged-particle beam weapons. If your preferred gaming experience is to "role play" as the commander, and you want to play a game to determine if you can "do better" than Napoleon at Waterloo or Lee at Gettysburg, then you probably stopped reading this article long ago. While I have nothing against that sort of thing, and have been prone to role-playing from time to time myself, I don't believe we should come away from an historical miniatures game believing that we have demonstrated an "alternate" result to history that would only have occurred had we personally been in charge of the battle. To enter into a game with our 21st Century perspective, in the relative comfort of our game rooms, with neither our careers nor our lives at stake, and to believe that if Lee or Napoleon would have just simply followed the same course of action that we did in our game that they would have emerged victorious, is a monumental stretch.

In order to play the "maneuver warfare game," we need to be prepared to surrender some of the omnipotence with which we are accustomed in controlling our miniature armies. However, we will also have the opportunity to inflict the same on our opponent, and that is the reason why we want to play the maneuver warfare game.

Therefore, the true maneuver warfare game must provide a means and the incentive for the practice of maneuver warfare in terms meaningful to the game. This can only be accomplished by game mechanics that reward a player who applies maneuver warfare principles and by penalizing the player who falls victim to them. Rules that simply randomly inject the "fog of war" into play fall short of the true maneuver warfare game. If "noise" is applied equally or arbitrary to both sides in a game, the net result is only a complication of the rules that bog down play.

An example of this is "variable movement" in which part or all of a unit's movement rate is determined randomly (e.g. by a die roll). While this may more accurately model the uncertainty and variability in movement rates observed in the real world, it adds nothing to the "game" because there is no risk/reward tradeoff. Simple "randomization" does not motivate or reward players for their actions because the results apply equally to both sides and is not controlled or influenced by the actions of either player. The maneuver warfare game should enhance the gaming experience, not stifle it.

MANEUVER WARFARE: TIME, SPACE AND MIND

MANEUVER WARFARE: TIME, SPACE AND MIND

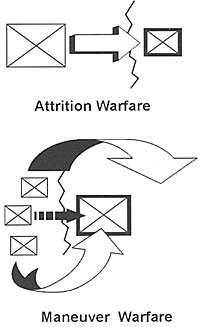

Before we can incorporate maneuver warfare into our miniatures games, we need to understand more about maneuver warfare. In simple terms, there are two different approaches to fighting a war: attrition warfare and maneuver warfare. Attrition warfare can be viewed as the more "physical" form of warfare while maneuver warfare is the more "mental" form of warfare. In attrition warfare, each side trades blood and treasure until one side (or both) no longer desires to pay the price of continuing the war and negotiates surrender. Attrition warfare pits friendly strength against enemy strength and aims at defeating the enemy by destroying him. This often requires a force more powerful (larger) than that of the enemy, particularly if the enemy has a defensive advantage like entrenchments or a "home advantage."

Despite the name, maneuver warfare is not limited to the movement of friendly forces to where they are in a better position from which to attack the enemy. In maneuver warfare, the objective is to eliminate the opponent's capability or willingness to wage war, often by means other than direct destruction of his forces. Through maneuver warfare, a smaller force can defeat a larger force, not by destroying the enemy, but by defeating him. Maneuver warfare pits friendly strength against an enemy's weakness (vulnerability) and wins by destroying his will to fight without necessary destroying his capacity to fight.

The figure illustrates the conceptual differences between attrition and maneuver warfare through example. Using attrition warfare, a larger friendly force directly attacks a smaller enemy force defending behind prepared positions. The fight will be brutal and bloody, but if enough friendly forces can be brought to bear, the enemy can be destroyed. In the maneuver warfare example, a smaller friendly force (subdivided into three even smaller forces) attacks a larger enemy force by first fixing the enemy in place with a threat to his front.

Next, supporting enemy forces execute a double envelopment through a flanking maneuver and an airmobile deployment into the rear of the enemy. The psychological effect of an enemy suddenly appearing in the rear or on the flanks, and the very real disruption of communications, supply, and command control that those forces can cause, may be enough to cause the larger enemy force to abandon the prepared positions (and consequently be attacked when moving in the open and vulnerable) or to surrender outright. The enemy has been defeated without being destroyed.

Col. John R. Boyd, USAF, Ret. combined the theories of Sun Tzu, Carl von Clausewitz, B.H. Liddell Hart, and others into a "unified" theory of maneuver warfare. At the heart of Boyd's concept of maneuver warfare is the psychological component of warfare. Boyd expands the "dimensions" of warfare beyond the physical aspects of "time" and "snare" to

include the dimension of the opponent's "mind." According to Boyd's theory of maneuver warfare, by generating ambiguity, isolation, confusion, and panic in the opponent's mind, a commander can achieve victory without bloody and "decisive" battles. In attrition warfare, the side with the "bigger battalions" (greater potential energy) in the right place at the right time will usually win, because that side will be able to generate the higher level of kinetic energy (violence, shock, physical destruction). In maneuver warfare, the emphasis is on lowering the potential energy of the enemy before (or in lieu of) the battle. This can be accomplished in many ways - psychological warfare, dislocating the enemy from supply/command, misinformation, etc. The enemy will then be able to convert less potential energy into kinetic energy in battle. If the enemy senses that his potential energy has dropped too low, he may chose not to fight at all, and victory is achieved without battle.

Col. John R. Boyd, USAF, Ret. combined the theories of Sun Tzu, Carl von Clausewitz, B.H. Liddell Hart, and others into a "unified" theory of maneuver warfare. At the heart of Boyd's concept of maneuver warfare is the psychological component of warfare. Boyd expands the "dimensions" of warfare beyond the physical aspects of "time" and "snare" to

include the dimension of the opponent's "mind." According to Boyd's theory of maneuver warfare, by generating ambiguity, isolation, confusion, and panic in the opponent's mind, a commander can achieve victory without bloody and "decisive" battles. In attrition warfare, the side with the "bigger battalions" (greater potential energy) in the right place at the right time will usually win, because that side will be able to generate the higher level of kinetic energy (violence, shock, physical destruction). In maneuver warfare, the emphasis is on lowering the potential energy of the enemy before (or in lieu of) the battle. This can be accomplished in many ways - psychological warfare, dislocating the enemy from supply/command, misinformation, etc. The enemy will then be able to convert less potential energy into kinetic energy in battle. If the enemy senses that his potential energy has dropped too low, he may chose not to fight at all, and victory is achieved without battle.

It is no coincidence that the "energy" analogy is so appropriate in describing the principles of maneuver warfare. Col. Boyd developed his theories of maneuver warfare during his career in the USAF, and through his analyses of air-to-air combat during the Korean Conflict he made significant contributions to the theory of energy management as it is applied to air combat maneuvering (ACM). Boyd later became a leading proponent of the lightweight, agile fighter concept that eventually produced the F-16 Fighting Falcon, and he later expanded these concepts to warfare (and human endeavors of all kinds) in general. For more about Col. John Boyd, read the fascinating book BOYD: THE FIGHTER PILOT WHO CHANGED THE ART OF WAR by Robert Coram.

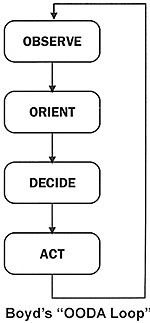

Boyd would bristle at calling maneuver warfare a "theory" because that word connotes a prescriptive, rigid doctrine with fixed responses to a given set of inputs. Rather, Boyd saw maneuver warfare as more of a mentality than a methodology. Maneuver warfare, as Boyd preached it, requires operating within rapid decision cycles through flexibility, adaptability, and mental and physical quickness. He called these decision cycles "OODA Loops" because the four major phases - Observation, Orientation, Decision, and Action - were repeated over and over again during a confrontation with the enemy.

To dominate the opponent on the battlefield, one's own decision cycle must be shorter (faster) than the enemy's. The goal of maneuver warfare is to render the decisions of the enemy irrelevant by creating new threats more quickly than the enemy could observe and react to previous developments. The best possible outcome is that the opponent will panic or become passive, and can be subdued with minimal losses and effort on both sides.

While structured, organized processes for conducting warfare were nothing new, Boyd shifted the focus from the decision cycle of friendly forces to that of the enemy. Even if one's own decision cycle suffers from "friction" and the "fog of war" and can not be improved, an advantage could be gained in warfare if the enemy's decision cycle could be lengthened (slowed down) through the deliberate actions of friendly forces. William S. Lind in his book MANEUVER WARFARE HANDBOOK describes maneuver warfare as "out-decision-cycling" your opponent. That means observing, understanding, deciding, and acting at a faster tempo than the enemy does by a combination of minimizing "friction" in your own cycle while maximizing that of the other side. On the rapidly developing, violent and chaotic battlefield, uncertainty is a fact of life, but Boyd says that the practitioner of maneuver warfare must embrace uncertainty and use it as a tool against the opponent.

Why should miniatures rules need special rules or game mechanics to model maneuver warfare? Shouldn't the natural psychology between the players be adequate for creating the "friction" of battle? I believe not, because there is a difference between the "experience" of warfare and the "process" of warfare. Since a game cannot recreate the experience of warfare, players are not likely to react to situations and behave the same way that they would if they we involved in actual combat. If a wargame is intended to simulate the "process" of warfare (and not all do or should!) then it must include special rules to constrain, control or limit the actions of the players acting as battlefield commanders.

THE MANEUVER WARFARE GAME: CHAOS OR CONTROL?

THE MANEUVER WARFARE GAME: CHAOS OR CONTROL?

Sam A. Mustafa wrote a very interesting article in MWAN #124 (pp.76-79). Sam's article contrasts what he calls the "chaos" versus "control" approach to wargame rules. Controltype rules, according to Mr. Mustafa, provide for a very detailed and orderly sequence of play, fixed periods of time, and generally very predictable and reproducible mechanics of play. Chaos-type games "shuffle" events (or at least opportunities for events), vary the amount of real time being modeled within a turn or phase, and generally seek to model the unpredictability and lack of control the commander typically faces in a real battle.

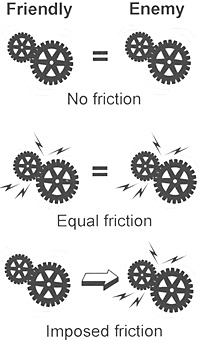

Maneuver warfare, I believe, can be modeled best in a chaos-type rules system. However, the key to the maneuver warfare game is that "chaos" (or "friction") should not be arbitrarily, randomly, or equally applied to both sides - it should be created or prevented through the actions and decisions of the players themselves in order to gain an advantage. The maneuver warfare game should add or subtract chaos ("friction") to one side or the other, depending upon the actions of the opponent. This is the critical ingredient to both a "realistic" game and a more enjoyable gaming experience based on maneuver warfare - the opportunity to create more chaos for your opponent while preventing chaos on your side. Players who dislike chaos-type rules usually view chaos as an unnecessary complication. This view is probably justified if the amount of chaos on both sides is fixed and equal. However, if a player can influence the amount of chaos his opponent faces, then chaos becomes a valuable strategic tool. This is the essence of maneuver warfare.

The next figure conceptually illustrates the difference between simply modeling "chaos" and the maneuver warfare game. If rules do not model "friction" (and many good rules don't), factors such as command and control, communication, supply, morale, leadership, etc. are simply ignored and the "machinery" of the game proceeds equally smoothly on both Friendly and Enemy sides of the table. If "friction" is introduced, the "gears" turn less smoothly and factors such as those listed above can impede the ability of the players to exert complete control over their forces. While this may more accurately portray the experience of warfare from the perspective of the battlefield commander, it doesn't especially add anything to the "game."

Both sides are impeded roughly equally by the "fog of war" like two runners on the same muddy track. However, if we provide rules which allow one side (the Friendly side in the figure) to create and impose more "friction" on the other (Enemy) side, so that the intentions of the opposing player are frustrated, not randomly, but as a result of our superior application of the principles of maneuver warfare, then we have else something indeed! Now we can tip the scales of the battle not through sheer force of arms, but through actions which result in a "failure of the will" of the opposing commander.

Of course, the rules must impose restrictions or actions upon the player who has suffered the effects of a maneuver warfare operation because the player may (as described earlier) be unfazed by our actions while the "real life" commander would be.

THE MANEUVER WARFARE GAME: EXAMPLES

Before we set out to design some maneuver warfare games or our own, it might be helpful to look at a few existing rules and game mechanics that model maneuver warfare. Most miniatures rules do a reasonable job of modeling the physical aspects of war - ranges of weapons, effects of damage, movement, etc. In Boyd's terminology, these are factors of "time" and "space." Most rules usually fail to adequately model the human aspects of warfare - Boyd's third dimension of "mind".

The most common "human" element modeled in miniatures rules is "morale." Morale is typically used to decide the breaking point of units (or individuals) under fire, or to determine whether or not a unit would consent to perform certain "difficult" actions (close assaulting an AFV, charging an entrenched position, etc.) Simple forced retreats (or advances) after combat are morale-modeling mechanics employed in the simplest of rules, included DE BELLIS ANTIQUITAS (DBA).

Morale is a component of what Boyd calls the "mind" dimension, but is not all of it. An individual may have good morale but still take no action against an opponent, even when to do so would ultimately improve his chances of winning (or at least survival). This can happen as a result of enemy deception, lack of communication with superiors in an overly-centralized command structure, misunderstanding, etc. All of these influences can be purposely created (or at least magnified) by an opponent. Reducing what Clausewitz calls the "friction" of warfare in the one's own decision making process, and creating more "friction" in the mind of the opponent (Boyd's expansion of Clausewitz), is a critical component of maneuver warfare. Modeling this in miniatures rules can be a real challenge!

The concept of unit "cohesion," or "order," is often designed into miniatures rules. These rules try to translate the psychological impact of combat into a tangible effect on the unit's ability to fight. FIRE AND FURY, popular brigade-level rules for the American Civil War, uses clever game mechanisms to model the effects of the battlefield experience and environment on the ability of a unit (brigade) to rally, change formation, and move. Brigades usually start out "fresh" but the cumulative effects of taking fire (modeled by removal of stands from the brigade) eventually causes the brigade to reach "worn" or "spent" status.

Brigades that are "fresh" are more likely to rally and move freely, while brigades that are "worn" are less likely to move, and brigades that are "spent" are very likely to rout and depart the battlefield entirely. This game mechanism does a pretty fair job of representing the effect of increasing "friction" on the effectiveness (OODA Loop cycling speed) of a unit in combat. Brigades that have had enough of "the show" tend to stop doing what you want them to do and may even leave the player's control completely. What FIRE AND FURY fails to do is to extend this same idea to the army level (more about this later).

Leadership is another critical component that is modeled in some wargames, but not all. Leadership can either increase or decrease friction on either side of a conflict. In the real world, good leaders on your side are a good thing - they react to fluid situations, making decisions that might not follow standard operating procedure (SOP) because they decide SOP does not cover the current situation, etc. They also inspire troops and improve morale. Bad leaders either freeze or make stupid or rash decisions. As managers of "friction," leaders should be prime targets in a maneuver warfare game. Removing the good leaders on your opponent's side creates more "friction."

It is no coincidence that TAHGC's ADVANCED SQUAD LEADER (ASL) game system has the word "leader" in the title. Leaders play a critical role in ASL. They improve the movement rate, firepower, and influence the morale of units that are stacked with them in the same hex. The implication is that the leader is more skilled at problem solving, or that the soldiers' motivation is higher in the presence of a leader than it would be otherwise. Good leaders oil the warfighting machinery, and taking them out by deliberate action allows your opponent's friction to increase.

The sequence of play game mechanic used in almost every rules system bears more than an analogous relationship to Boyd's OODA Loop. Because of it's manipulation of the sequence of play, the PIQUET rules provides a wonderful opportunity for employing the concepts of maneuver warfare in a wargame. Piquet uses Sequence Decks of cards rather than a fixed Sequence of Play. The "good" cards in the deck allow units to Rally, Close Assault, Move, Reload, and take other actions. Some of the cards are "do nothing" cards (Milling Around, etc.). The genius of PIQUET is not in the "re-ordering" of the sequence of play but in its ability to change the characteristics of the sequence of play, particularly the frequency at which actions can occur, as a result of events or developments during the game.

This is accomplished, as a consequence of significant "bad" events, by the replacement over time of action cards in the Sequence Deck with cards that do not allow a player to take any action at all. As one side experience losses or other "bad things" (loss of a leader, capture of a key terrain feature by the enemy, or other scenario-specific events or conditions) some of the "good" cards are removed from that side's sequence deck to be replaced by more of the "do nothing" cards. This effectively expands the decision loop for that side and models the effect of "friction" on the commanders ability to act quickly. Because of this game mechanic, PIQUET does more to incorporate the most critical aspects of maneuver warfare (fog of war or "friction," asymmetrical unfolding of events, use of time as a weapon, etc.) than any other set of rules that I know of. This was not by accident, but by clever design. Bob Jones' Theory of Piquet (http://www.piquet.com/theory.htm) reads as if Boyd himself wrote it.

THE MANEUVER WARFARE GAME: SCENARIO DESIGN

We now begin our efforts to add a dimension of maneuver warfare to our miniatures wargames by looking at what can be done through scenario design.

Robert Leonhard in his book THE ART OF MANEUVER defines the operational level as the intermediate level between military strategy (planning how to impose national will using force of arms) and tactics (how to fight a battle). Wargamers are probably more familiar with the term "campaign" but the modern term for a linked series of actions in a theater is "operation" (that is why it is called Operation Desert Storm, Operation Iraqi Freedom, etc.). The battle is the basic building block of operational art, and a good commander should only enter into battle if it supports the overall military strategy. The enemy is pre-conditioned for battle through maneuver warfare at the operational level, through such activities as disruption of lines of communication, decapitation strikes aimed at leadership, and disruption of the enemy's own plan by threatening a vulnerability.

So, we may decide that in order to incorporate the effects of maneuver warfare in a wargame, that wargame will either have to be at the operational level or above, or, if at the tactical (battle) level or below, games will have to be played in the context of a campaign. The campaign (where "operational art" is practiced) is the appropriate level for the application of maneuver warfare. How, then, would a miniatures game played at the "tactical" (battle) level provide the opportunity to employ maneuver warfare?

Adding an operational dimension to miniatures gaming does not require playing an entire campaign. The operational situation, and the players' ability to shape it through maneuver warfare, can be modeled with special scenario rules that can be applied to even a single battle. Before gaming a battle, players can agree on a number of "operational options" available to each player which could have an impact on the tactical battle they are about to game. Players must then make trade-offs because they are constrained to a fixed "budget" of operational and tactical resources. They must choose how their limited resources are applied, with the option of employing maneuver warfare practices or not.

For example, a player may give up a regular infantry platoon from the forces available for a particular scenario in order to attempt a "pre-game" commando raid aimed at transportation centers behind enemy lines, with the result being that the enemy re-enforcements are potentially delayed or prevented. The commando raid need not be played out with miniatures, but can be a simple 1 D6 roll with the results ranging from "Raid failed, no effect" to "All reenforcements delayed 1 D 10 from the original arrival time." Or, aircraft could be allocated to either close air support (in which case they appear on the table during the game) or the player could opt to use them for disrupting fuel supplies in the enemy's rear, with the result being that the movement rates of all enemy armor on the board are reduced during the game.

In an ancients game, a player could decide to dedicate an elite unit (which then is unavailable for the battle) by sending them after a high-ranking enemy leader. If their mission is deemed successful and the targeted leader is assassinated, the enemy loses that leader for the battle. Again, these events need not be gamed out, only rolled for based on an agreed-upon probability of success. Before set-up and play with miniatures begins, each player secretly selects from the available options and then simultaneously reveal their choices. Rolls are made, and any adjustments in the tactical situation, including initial deployment of forces, availability and arrival schedule for re-enforcements, and other rules are then duly noted and applied during the game.

I wrote a programmed campaign set in Normandy 1944 (see MWAN#131) that uses some of these principles in modeling maneuver warfare. Players can opt for historical operational conditions, or they can experiment with alternate history by picking a different strategic situation in which to conduct the campaign. For example, what if the ruse to fool the Germans into thinking that an invasion of Norway was imminent (Northern Fortitude) had failed, and the Wehrmacht re-deployed forces from Norway to northern France in early 1944? What if the Allies had planned a long pre-invasion bombardment of the Normandy coast? What if Hitler had not ordered the Me-262 into action as a tactical bomber, but instead allowed it to be fully utilized as a fighter against the Allied airborne assault?

None of these events or decisions are actually gamed out in the campaign, they are only reflected in the force composition, availability, and other special rules during the battles of the campaign. This allows the player to make their own choices and customize 1 their style of warfighting toward either attrition or maneuver warfare before the battle even begins.

Not all maneuver warfare need occur at the operational level, outside of the scope of the miniatures game. Scenarios can also be designed to include specific "trigger" events which, when the occur during the play of the game, result in a penalty or restriction ("friction") to be imposed on the affected player. These events would have to be of the kind that, in a real battle, would have a serious psychological impact on the forces and commander involved. For example, if a specific bridge in the rear of one player's forces is captured during the battle, the morale of that side, seeing their only avenue of escape cut off, would plummet. The effect of this morale crisis could be modeled using whatever game mechanism that the rules happen to provide (army morale, etc.). The key is, the players are given the option to use available assets in an attrition warfare manner (headto-head against enemy forces) or to attempt movement, feints, raids, decapitation strikes or other limited or indirect actions which create threats and cause disruption and dislocation per the tenets of maneuver warfare.

It is this decision process that we intend to design into our rules and scenarios. We want games that reward the player that, acting as a commander, invests in actions which, in real warfare, would create confusion, panic, and a growing sense of defeatism - a "failure of the will" to fight - in the opposing commander. Likewise, we want games that punish the player who neglects to do the same to the opposing player and/or falls victim to the maneuver warfare devices of the opponent.

THE MANEUVER WARFARE GAME: GAME MECHANICS

If we are to model the effects of maneuver warfare (shock, ambiguity, deception, etc.) on an opponent, we must be able to alter the tempo of one side or the other. The "sequence of play" can be viewed as the decision cycle of the wargame (this analogy is somewhat inaccurate but not necessarily misleading). What is needed, therefore, is a mechanism for changing the tempo at which players can cycle through the sequence of play. We continue our quest to design the maneuver warfare game by looking at what can be done with the mechanics of two popular existing rules sets.

FIRE AND FURY

As described previously, FIRE AND FURY uses are remarkably compact and elegant game mechanic to model the psychological effects of warfare on the effectiveness of units in combat. The Maneuver Procedure usually grants full movement capabilities to fresh units in good order, while at the other extreme, "spent" units in disorder can quit the field spontaneously. The restrictions imposed by the Maneuver Procedure (by constraining the "Action" component of the OODA Loop) represent the result of "friction" on the battlefield, including aspects like losses of lower-level leaders, fear, breakdown in communications, etc. within a unit. This mechanism works well to model battlefield psychology at the unit (brigade) level, but it falls short by failing to reflect the psychology of the overall commander - a key factor in maneuver warfare.

A simple maneuver warfare fix to the FIRE AND FURY rules is to define a few conditions or events that lead to a general reduction in the morale status of the army. For example, a scenario could include a provision that if one side accumulates a 2:1 advantage in Victory points (which in FIRE AND FURY are awarded for reducing brigades to worn or spent status, killing leaders, etc.) or a particular terrain feature is captured (a hill or bridge, for example) then all brigades on the disadvantaged side become "worn" or "spent" if they are not already so.

If the game is refereed, the players would not be explicitly told of this rule but instead would be briefed at the beginning that a particular terrain feature is very important, for example, and must be held "at all costs." Only if and when the terrain changes hands would the condition be imposed on the disadvantaged army. A similar result could be obtained by applying a negative die roll modifier (DRM) to the Maneuver Table roll for all brigade Maneuver checks within an army that is suffering from the effects of maneuver warfare. Either method would have the effect of severely skewing the Maneuver results for the affected army, possibly leading to a general route like those experienced by the Federal forces at First Bull Run and several other battles in the Eastern theater of the American Civil War.

FLAMES OF WAR

Here is a relatively simple method of retrofitting the "maneuver warfare game" into existing rules. I have chose the popular FLAMES OF WAR rules as an example, but this method will work with any miniatures rules and requires only regular playing cards in addition.

FLAMES OF WAR uses a simple "I Go, You Go" turn sequence and the sequence of play within each player turn is Move, Shoot, and Assault. This means that every turn every unit will get a chance to move or conduct fire or assault combat. While there are psychological effects modeled at the unit level (Morale, Pinning, etc.), there is no provision for the cumulative effect of "friction" on the battlefield. The following game mechanic attempts to remedy that shortcoming.

Each player needs two (2) decks of regular playing cards with identical reverse designs (backs). Shuffle one complete deck (the Initiative Deck) but remove the Jokers, Aces, and all face cards from the other deck (the Replacement Deck) before shuffling it. Next we assign an Initiative Rating to each unit (usually platoons). Since the rules already assign a Motivation rating to each nationality for each phase of the war, we will assign the numerical Initiative rating based on that.

A lower Initiative number is better, so we assign for example an Initiative rating of "4" for a Fearless unit, "7" for Confident, and "9" for Reluctant troops. Players still alternate taking turns, but at the beginning of each player's turn the player draws one card for each unit from that side's Initiative Deck. If the card drawn for a unit is of a rank equal to or greater than the Initiative rating of the unit, the unit may perform all actions that unit could normally perform in a turn - Move, Shoot, and Assault. If a unit is dealt a card that is of rank LOWER than that unit's Initiative rating, then that unit may NOT perform any action in that turn. (The Joker is a "wild" card and always enables the unit for which it is drawn to perform a turn.)

During play of each turn, award the points values of any vehicles or teams that are eliminated to the player that eliminates them (point values for each vehicle and team are listed in the FLAMES OF WAR rules). Players may also want to assign an agreed upon points that are awarded to either side keyed off of a specific event, like "Capture the bridge - 500 points" or "Cross the road - 250 points." These events should be consistent with the precepts of maneuver warfare, that is, events that would cause disruption of com--, munication, a decline in morale, panic on the part of the commander, etc. Following the player turn in which a Joker is dealt, total up the points awarded to each player since the turn in which the last Joker was dealt (or the beginning of the game, whichever is later). Next, determine the ratio of points awarded to each side by dividing the greater total by the lesser total. If the difference in points is significant, the make-up of the Initiative Deck of the side with the lower point total will be adjusted before the next turn begins to lower the average rank of that deck (and therefore make it less likely for a unit to draw a card of equal or higher rank than that unit's Initiative rating).

For example, if the ratio is less than 1.5, the difference is insignificant so the point tally is reset to zero for each side and each player re-shuffles the Initiative deck and play resumes, following this process again at the end of a bound in which a Joker was dealt. If the ratio is 1.5 or greater, remove at random one card from Initiative deck of the player with the lower total for every 0.5 points or fraction thereof above 1.5 (1 card for 1.5 to 1.99, 2 cards for 2.0 to 2.49, 3 cards for 2.5 to 2.99, etc.) Replace the cards removed from the Initiative deck with the same number of cards drawn (at random and without looking) from that players' Replacement deck. Shuffle the Initiative deck and resume play, following this process again at the end of a bound in which a Joker was dealt. Players will have to tune the actual points differences they use (and the number of cards replaced) based on their own still of play and experience.

The net effect of this system should be, as one side suffers "bad things" and the average rank of cards in the affected side's Initiative Deck drops, that side's units will have less and less opportunity to move and fight compared to the forces on the opposing side. This represents the real-world decline in the efficiency of the army as commanders begin to hesitate, troops fail to obey orders, fear, uncertainty, and doubt begin to dominate the thinking of troops and commanders, and things generally go to Hell. If the opponent presses the advantage, the result can be an even further deterioration of the situation and an eventual paralysis and collapse of the affected army. Chaos begets chaos.

THE MANEUVER WARFARE GAME: A TIME AND A PLACE

Should every game we play, and all rules we use, provide a mechanism for employing the principles of maneuver warfare? Certainly not. Maneuver warfare is not historically accurate (that is, not "period") for many historical scenarios. The increased complexity of the maneuver warfare game may mean it is not appropriate for "beer and pretzels" rules aimed at pure fun. However, if you want to better understand why Stonewall Jackson's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley managed to tie down a vastly numerically-superior foe, or how the Wehrmacht rolled over a comparably-equipped French Army in 1940, or why the Iraqi Republican Guard was a virtual non-starter in 1991, and you want to play games with rules that let you repeat those successes, then the maneuver warfare game may be what you are looking for.

Back to MWAN # 133 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Legio X

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com