SOMETHING IN THE AIR ...

From the shelter and shade of his command tent, Quintus Cicero, trusted legate of Gains Julius Caesar and commander of the veteran Eleventh Legion, awaited the return of his allied cavalry scouts. During this interval, he busied himself by catching up on some long neglected correspondence. He spent almost another hour reviewing the reports of his subordinates. It never really ceased to amaze him how much it took to keep a single legion in the field: so much food, so much water, so much of this and that so that the lists seemed without end. Taking a moment to clear his head of these facts and figures, Quintus Cicero stepped into the morning sunlight outside his rather large field tent. He watched with quiet approval the camp routine of his centurions and their charges. A veteran of three years campaigning, Quintus had become adept at "smelling" battle in the air. Sulpucius Galba, his friend from childhood through introduction into legion service and more, had been for these same three years, his second-in-command. Only at the proper times-never in front of or in ear shot of any rankers or tribunes-would Sulpucius sometimes tease Quintus about his large nose.

On this particular summer morning Sulpucius was not present; being occupied with some logistical concern at the far side of the marching camp. Quintus stood with his hands on his hips and turned his face to the western sky. He took in a few deep breaths, paused, and then, there it was. That familiar tickle just on the edge of his nose. There would be a battle today. For a moment, he considered sending a dispatch to Caesar but then dismissed the idea. Better to wait until the coming action is done and victorious, the legion returned to its protective camp. His face warmed by the sun and his mind already thinking ahead toward the promised engagement, Quintus turned to go back to his administrative duties. He had not taken two steps when a shout went up from the guard tower at the front gate: the scouts had returned. The administrative tasks would wait! There would be battle!

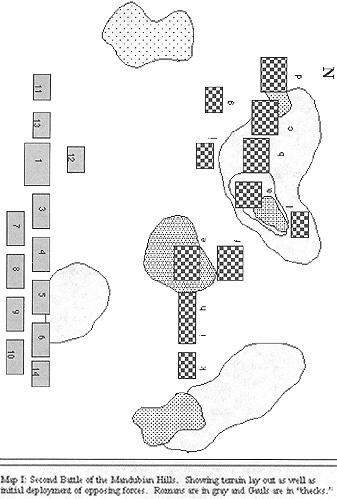

In less than an hour, the cohorts of the Eleventh-eager to bring the barbarians to battle-were marching through the main gate. The two centuries of the Second Cohort, along with an equal number of camp followers and slaves, stayed behind to garrison the camp. Quintus rode at the front of the procession, accompanied by his lieutenants and of course, Sulpucius. Two troops of auxiliary horse rode some distance ahead of the column, spread in a wide skirmish formation.

Some three hours after leaving the protective ditches and walls of their camp, the advance parties of the Eleventh sighted the warbands sitting in the same place as they had been since the early morning light revealed their positions. Quintus Cicero made a quick personal reconnaissance of the enemy line and then galloped back to give orders to his assembled commanders. Battle commands given, Quintus maneuvered his large chestnut mount to a position behind the First Cohort. The Eleventh, as it had many times before in his three year role as commanding general, deployed smartly to the right of the double-strength cohort.

Nodding curtly to an aide, the aide then signaled to the small corps of musicians standing and waiting to the right of the general's retinue. The still afternoon air was shattered by three long blasts from the trumpet men. Immediately after, another section began thumping a steady martial beat on their large, uniform drums. Instructed by these notes, the heavily armed and armored infantry of the Eleventh began their advance. All the while, under the watchful and fierce eyes of thousands of strangely painted and colorfully clothed savages across the plain.

FIRST MOVES

Senior Tribune Sulpucius Galba advanced with the legion infantry. As he was on horseback, he made sure that his mount kept an appropriate pace so that he could maintain his position behind the Fifth and Sixth Cohorts. The gentle hill that all were crossing was not difficult terrain, but the formations became slightly disordered anyway. No matter at this distance from the enemy. The line could be dressed when the men were off the hill. The auxiliary archers were advancing in conjunction with the general advance and the Tenth Cohort was following per plan. For some reason that was communicated to the Senior Tribune only after some time had elapsed, the Eighth and Ninth cohorts were not moving. Sulpucius Galba reined his horse to stop, making sure his command did not stand in the way of the advancing cohorts. Turning, he saw the solid blocks of legion infantry standing in place. He swore under his breath and then directed one of his junior cadets to "kindly" inform the men of the Eighth and Ninth to "get with the program."

No sooner had this reminder been sent when a ragged line of Gallic light infantry and cavalry dashed toward the advancing Roman line. Hurling shorts spears and some javelins, as well as insults and derision, the Gallic skirmishers showered the front ranks of Galba's subcommand. Fortunately, the missiles had very little effect. Most missed their marks and most of the rest simply glanced off sturdy shields. The Gallic horsemen however, did a little more than bother the legion infantry.

Catching the Sixth Cohort as it negotiated the terrain of the gentle hill, the light horsemen were able to take advantage of the few gaps that appeared in the formation. Urging their mounts forward, the cavalrymen stabbed and slashed with spear and sword, bringing down more than a few of the heavy infantry. But the advantage was quickly regained by the veteran legion infantry. The pila were used as a defensive weapon, pricking the flanks of horses as well as the ribs of unprotected riders. In a matter of minutes, the Gallic horse were in flight, unable to take any more of the close combat. Their retreat was aggravated by a couple of volleys of arrows from the auxiliary archers who had been in place just to the right of this action. With their cavalry in disorder, the light infantry pulled back as well. Biturgo raised himself up on his magnificent warhorse and waved his sword. Slowly, the javelinmen and light cavalry under his charge began to reform.

Standing with his warrior brothers in the dense wood of the center of the line, Gobannito watched the Romans advance. The center of their line was marching straight across the field and would be up to the edge of the woods very soon. He directed his gaze toward the right and watched the rest of the Roman line drawing up. It looked to be another couple of cohorts and some light troops and a small wing of cavalry. The battle plan and subsequent dispositions ordered by Daderax seemed that they would work. The four warbands to his right should prove more than a match for the left of the Roman line. His attention returned to the line of gray men moving across his front, Gobannito looked to the men on his immediate left and right. They were the strongest and bravest of his band. As tall or taller than he was, and each with a large shield, spear and very sharp long sword. The drumming of the Roman musicians played in his ears. Gobannito could feel the slight tremble of the ground as the Roman soldiers tramped closer and closer to the woods.

Prefect Gaius Trebatius made sure that the First Cohort was fronted by a strong skirmish line of auxiliary javelinmen and that its left flank was secured by the archers and cavalry contingent. He had no doubt that the First could look after itself, but if his command could absorb some of the attention that might be directed at the First-as well as hand out some punishment to enemy units in proximity-then so much the better. The Legate Quintus Cicero was riding behind the First, after all. Soon enough, missiles were flying back and forth on this major flank. Sling stones bounced off the small shields of the skirmishers. Some even reached into the first ranks of the main cohort. Arrow shafts were sent in reply. At this range however, the missiles were simply a nuisance. Neither side suffered reportable losses.

A SURPRISE GONE WRONG

When the Romans were close enough so that Gobannito could see the whites of the eyes of the leading legionaries, he gave a loud and long battle cry and began to run through the trees toward the line of heavy infantry. His war cry was echoed by more than several hundred throats, and his almost vainglorious dash through the trees was followed by as many fierce warriors. The wood line seemed to shudder with the screams and advance of so many brave warriors.

Just outside of the tree line, the Roman cohort halted and the men drew their short swords and held up their shields. In the rear ranks, a halfhearted volley of pila was launched. These wicked missiles did little to stem the onslaught of the rushing warriors; most of the barbed points being deflected by tree limbs or simply jutting into the ground. Prevented by the nature of the terrain from massing numbers against this armored front, the Gauls struggled to find a weakness in the Roman line. Shield was used against shield, sword against sword as well as spear against sword. Training and drill was pitted against ferocity and lack of tactics. Training and experience would win out. Frustrated by the resiliency of this human barrier, and severely wounded by the workmanship of the short sword, the Gallic band retreated back into the woods. Both sides had been blooded; both sides left more than a few score of men on the ground. The Romans had held against this first rush, however. His face splattered with blood, the senior centurion of the Fifth set about to reorganizing his cohort.

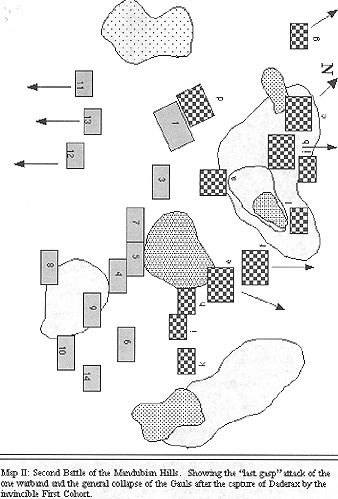

Excited by the war cry of Gobannito and his followers, the mass of warbands on the hill to the right began to move forward. The Romans were still some distance away, but this call to battle and the subsequent sounds of combat proved irresistible. Like some painted and halfnaked rolling wave, one warband and then the next spilled over the hill and onto the plain. Daderax himself was at the apex, followed by his "elite" warriors and, extending to the right, nearly two-thousand "regulars." The frenzied warriors were unable to reach the Roman formations, however. The distance had been misjudged and now, Dadereax and his troops found themselves in a kind of exposed position: on the wrong foot and having lost any advantage afforded by the height of the Mandubian Hills.

Quintus Cicero, seeing immediately that the Gauls had wasted their one advantage, ordered the First and Third Cohorts to charge. With orders to protect the left flank, the Prefect Gaius Trebatius ordered his cavalry troop and javelin infantry to join in the attack. As one, the Roman units moved forward and made contact with the roiling mass of Gallic warriors. The Third Cohort discharged two volleys of pila and then drew swords and waded into the ranks of the "elite" warband. The First Cohort followed quickly, sending even more missiles into the warband just behind Daderax. The auxiliary units on the left end of the line sold themselves dearly to buy time for the legion infantry. Outnumbered by two to one and in one case, three to one, the javelin-armed light troops and cavalry were very roughly handled. The Gauls hacked and slashed; cutting through small shields as if they were not there and so, wounding and killing man and beast by the dozens.

Though stung by the shower of pila, the "elite" warband withstood the initial attack by the Third. It would have to be close in work. The melee went back and forth. The neighboring warband however, could not stand up to the formed ranks of the First. Something like a hundred men went down in that first minute of combat and in the next minute, the heart had gone out of the warriors. Surprised by this sudden turn of events, Daderax found that he and a few stalwarts had been surrounded in the swirling melee. He took three Romans down before he suffered a grievous wound in his left arm and was forced to yield. Binding his hands quickly, a detachment from the First took him back toward the reserve of the cohort.

Their bloodlust raised, the victorious Romans continued their attack. Turning slightly to the left, the men of the First launched a second charge (this one without pila preparation) into the next warband in line. These warriors had just routed the auxiliary javelin infantry and were not quite ready to meet this new threat. Shield bosses and short swords made quick work of this tribe too, though at less cost. These Gauls did not stay in a one-sided contest. Seeing that their brothers had been beaten and hearing - for the word had spread rapidly - that their leader had been lost, these fierce warriors also lost heart and turned and ran.

Unaware of developments on the other side of the central wood, Biturgo kept the Roman right occupied. His light troops could do nothing more than harass the cohorts deployed on this flank, so harass they did. The light horse were particularly irritating, galloping up in small packets of troopers and throwing missiles into the close ranks of foot soldiers. Sulpucius put an end to this when he brought his archers forward. These auxiliaries would keep the attention of Biturgo's men. The Senior Tribune busied himself in bringing up more cohorts to support the Fifth. He sent another messenger to the lagging cohorts in the rear.

A LAST GASP

Dracco, chieftain of the remaining warband on the right of the Gallic line, bellowed a war cry and waved his long sword over his head. At the front of his fellow warriors, he ran forward into the serried ranks of the Roman infantry. Fortunately, they were not met by a shower of pila. (The Romans had expended all missiles in their first combat.) But they were met by a veritable wall of solid shields, interspersed with the deadly points of several hundred short swords.

The human wall bowed under the ferocity of their attack, but bellow and strike as they might, Dracco and his comrades could not break through this wall. In a very few minutes, the brave men of the Pictones found themselves being pushed back by, even trampled underneath, the wall as it began to advance. In a last desperate measure, Dracco and a few of his body guards threw themselves at the line of shields and sword points. Several legion infantry fell under this frenzied attack, but they were quickly and efficiently replaced. The human wall continued its advance. Losing men and losing heart, Dracco's contingent began to give way. In a very few minutes more, his once proud warrior band was streaming to the rear; running to avoid the shield bosses and sword points of the uniformed legionnaires.

Senior Tribune Sulpucius Galba drew up his horse just behind the ranks of the Fifth Cohort. These men, along with two other cohorts, were now drawn up in a line facing the central wood of the field. The ground was dotted with the bodies of both friendly and enemy dead and wounded; battle detritus from the first real combat of the afternoon. Sending terse commands to the senior centurions of these cohorts, Sulpucius Galba made sure that this reinforced line would be ready to meet any subsequent attack (surprise no longer an item of concern) issuing from this dense wood line. Shields in front, both pila and sword ready, nearly one thousand legion infantry waited in absolute and absolutely intimidating, silence.

The wait would not be rewarded, however. Bruised and thrown back by the veteran infantry of the Fifth, the barbarians began to think two and three times about launching another attack. The decision was made for them when, over on the right, their main line collapsed under the weight of the Roman advance. Turning and running like the other, now fugitive warbands, these warriors spilled into the ranks of yet another warband. In an instant, the message was spread and both warbands turned into one running mass of men bent on survival.

Biturgo, the handsome and proven swordsman son of Daderax, pulled up the reins on his mount and turned it away from the approaching Roman line. He had been tasked with the responsibility of holding and harassing the Roman right, but it was now quite apparent that his light troops could not complete their orders. True enough, the javelin men had run up on the waiting heavy infantry and thrown many missiles. But there was no effect. If any javelins had found their mark and brought down men, Gobannitio could not see this in the steady line to his front. His cavalry troops had scored some initial success. However, this was rather short-lived as the briefly disorganized Romans rallied and threw the horsemen back in some confusion. Exhorting his men for a second charge simply resulted in more empty horses wandering around this flank of the battle.

The Gallic son was trying to maintain some semblance of an organized front when a messenger from the main battle line found him. It was very bad news. In order that the tribe should not suffer the loss of its whole leadership, the bodyguard assigned to Biturgo guided their weeping leader to the rear.

AFTERMATH

Quintus Cicero, a senior legate among Caesar's veteran staff in long-haired Gaul, sat astride his chestnut horse and viewed the scene in silence. His own staff, veterans themselves of three years under Quintus, knew their work and the routine well enough. A group of some 250 prisoners, tall and fierce looking men and most of them walking wounded, were escorted past the temporary command post of the legion general. A smaller band of captured warriors followed. In this number was found the chieftain of the upstart tribe. He too, was walking wounded, having a rather nasty cut in his upper left arm and a lesser, superficial cut across his naked and painted chest. The enemy chieftain was silent as well. Stunned not so much from the wounds - which he endured with a quiet strength - but from the shortness of the battle, the loss of the battle, he looked silently upon his fellow tribesmen.

Then, turning to the right and looking over his broad shoulder, he took in the grisly picture of the field: scattered here and there, in some pockets more so than others, were the bodies of his warriors ...his fellow tribesmen. Much less in number, but perhaps more noticeable due to their armor and uniforms, he gazed upon the now still bodies of legion infantry. The chieftain's attention was redirected, and harshly so, by the shouted order of the centurion in command of the detail. His eyes now turned to the front, and with both hands and feet bound, the wounded chieftain began walking south with the other captives. The injury to his arm throbbed, but the pain was nothing compared to the sight of the field; nothing compared to the knowledge that he had promised his warriors victory yet had failed to keep that promise.

Back in their camp by early evening, the men of the Eleventh first tended to their walking wounded. Then, they enjoyed a hearty meal and a deserved night's sleep. On the morrow, they would return to the field in order to collect and dispose of their dead. Three days later, a courier arrived in Caesar's main encampment. He carried very good news.

COMMENTARY & ANALYSIS

COMMENTARY & ANALYSIS

In contrast to the report supplied in Mr. Grant's text, this adaptation was wargamed as a solo contest. To a large degree then, there were no plans formulated by either side. The "armies" simply lined up on opposite sides of the field and "had at it." Admittedly, and hindsight is always more clear, I could have shifted the Gauls around a bit more. Perhaps concentrating the cavalry on one extended flank instead of letting a powerful unit of medium horse sit out the fight. I wonder too, what would have happened if the central wood had been left empty and the ambush warband placed in one of the tree lines on either flank? To complete the second guessing: what would have been the result if the main concentration of Gauls had stayed on the hill and only rushed into combat when the time was right? We can speculate but never know, for the wargame is over and done.

Unlike Mr. Grant's narrative, wherein the Romans were engaged in a closer contest, this project resulted in a battle that was over shortly after the First Cohort met the warbands commanded by Daderax. With the Gallic chieftain wounded and in chains, the heart went out of the collected warbands. Personally, I was a little surprised by this development for, the intention of this effort was to test the revised Horse & Musket rules for Ancient period play. A wargame of four turns does not really allow for a "proper" test of the adapted rules and the mechanics of same. However, the quick result did seem to reflect historical evidence. If the Romans could withstand the initial charge of the barbarians, then the battle was essentially a foregone conclusion. Undisciplined troops simply could not stand toe-to-toe with drilled professionals.

Taking a brief look at the casualty count, one finds that the Gauls were rather roughly handled. The First Cohort was responsible for most of this bloodshed. The Fifth and Third Cohorts added some to this total. If the auxiliary horse had not been thrown away against the warband on the far left, one presumes that the Gallic losses would have been much greater. Then again, the pursuit might have been stopped by the unit of veteran horsemen maintained as a reserve by Daderax. As recorded however, this unit saw no combat on the afternoon of battle. In comparison, the majority of Roman losses were taken by their light troops: especially in those guarding the left flank of the First Cohort. A number of legion infantry did meet their fate on the field that afternoon, but no cohort was pushed to breaking point or forced to spread its survivors between the remaining units.

In terms of leader losses, the capture of Daderax was the signature event of the day. Not a single Roman centurion or officer of higher rank was wounded or killed in the action. The Prefect Gaius Trebatius did have a close call, however. This taking place when the cavalry and javelin infantry were routed by the advancing warbands. In this regard too, the revised rules seemed historically accurate.

In a general overview, I think the revisions worked fairly well. The Romans advanced without too much trouble and met the stubborn tribesmen at the base of the Mandubian Hills. In short order (very short order as wargaming time goes) the Gauls were thrown back, having lost their chieftain and more than a few hundred warriors. This story has been told. In the historical sense then, I think the rules worked. But what about in the wargame sense? Did the Gauls have any real chance? How well did the elements of the legion operate? Were there any problems with respect to command and control? These are the parts of the whole. Based on my limited and subjective viewpoint, I would remark that there is much more work and fine tuning to be done to the rules adaptation. As difficult as it is to take a step back from the solo commander's chair and review battle plans and tactics, it is perhaps more difficult to take a step back from the rule "writing" chair.

Turning first to the rules governing movement and maneuver, I would suggest that for solo play, the mechanics of Fire and Fury work very well. Stated another way, "absolute control" is taken away from the commanding player and the activity is subject to the toss of the dice. To be sure, if there are more positive modifiers than negative, a "good" result is very nearly assured. There are those instances though, when the best laid plans ... For example: the advance of the Roman legion went pretty well considering the tardiness of two cohorts in the second line. From what I understand by reading the military history of the period, the legion was a self-sufficient marching and fighting organization. It stands to reason then, as in the narrative supplied by Mr. Grant, that the elements of the legion would move in concert; each cohort and cohort commander knowing their role in the overall battle plan. On reflection, perhaps I should have granted more "control" on the Roman side of the field and kept the Fire and Fury mechanics (however tweaked) for the response and activity of the barbarian warbands. I have also been rethinking the attention I pay to the particular status of a unit. Here, I'm speaking of the disorder resulting from terrain and that which results from combat. I have not yet reached a conclusion, but I am leaning toward scrapping the entire idea: the splitting of semantic hairs seems more counterproductive than productive.

Turning next to a consideration of missile and melee combat, it seems that these rule revisions need a lot more work than those involving movement and maneuver. The firing procedures worked well enough, however. I do think a transcription of tables from Fire and Fury would speed up the process. (I spent some time cross referencing stands and die rolls between type pages and the actual ACW rule book!) Additionally, it was noted that while the number of modifiers in melee resolution were reduced from the amount in Vis Bellica, the process was still fairly involved. Given the performance of the seemingly invincible First Cohort, it appears that the melee results table will have to be rewritten. I mean really, in three separate contests and following one after the other, the First Cohort literally rolled over each warband. Sure, the cohort was disordered in the process, but not a single stand was lost. This struck me as somewhat unbalanced.

Morale is the final segment of the adaptation deserving a look. In large part, the issue of morale is addressed by the results tables of missile fire and melee combat. In terms of what happened during the course of this brief wargame, I think that these rules are pretty good. It seems reasonable - probable - that a tribe of Gauls would have second thoughts once their leader was taken captive or killed in a general action. It also seems reasonable that the warbands would not have much staying power in close combat, but rely more on that initial shock of their charge. Here, especially with respect to the surprise attack issuing from the wood line, do these adapted rules need more work. Even with the training and experience, the sudden rush of savage tribesmen into the front ranks, has to be a very trying event.

In summary, I think the idea to adapt these Horse & Musket rules was a good one. The adaptation and result however, earn just passing marks. The play test proved enjoyable, excitingly quick and to all intents and purposes, historical. And yet, as outlined above, much room for improvement remains. Only additional play testing will provide more evidence as to the strengths and weaknesses of the adaptation. This wargame report being the last in a series, the question then becomes one of purpose. For if the theme of Ancients is being shelved for the coming year, it seems imprudent to spend any more time wrestling with the complexities of rule revision and adaptation. This is not to state that, "I will wargame Ancients no more forever." On the contrary, I have become very interested in the Ancient period / world.

To a great degree, I think the blame, or more properly, the inspiration can be attributed to the books of Colleen McCullough's First Man in Rome series. Personally, I find this somewhat of an interesting "turn in the road" as I began my hobby journey with Napoleonics. From there, I graduated to W.W.II wargaming and then "visited" the ACW, the AWl and then went back to Napoleon. The Ancient period had never really been considered. Now, it seems that it is one of my favorites if not the favorite.

Looking back over my contributions to MWAN this year, I detect a strong bias toward things Roman. Of the six projects submitted, four were concerned with the history or workings of the Imperial war machine. Again, this is due to the work of McCullough. Although, I think Victor Davis Hanson deserves honorable mention. Robert Avery provided the material so that I could wargame Cynoscephalae. And Mr. Grant has been sufficiently credited and lauded.

I have neglected, but not purposely so, things Greek, Macedonian, Persian, Indian and Byzantine. I have neglected elephants and chariots; siege warfare and battles taking place off the shores of Italy, Africa and Greece. This list barely scratches the surface of the subject matter at hand. Perhaps instead of shelving the period entirely, I should simply shelve the idea and subsequent production of a "rough" adaptation of an established set of Horse & Musket rules to a different period?

Hmmm, I wonder what Caesar would do?

Back to MWAN # 132 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 Legio X

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com