His next battle lay not three miles beyond the town. Carbo had wasted no time in sending a warning to Rome about The Butcher's son and his three legions of veterans, and Rome had wasted no time in seeking to prevent amalgamation between Pompey and Sulla. Two of the Campanian legions under the command of Gaius Albius Carrinas were dispatched to block Pompey's progress, and encountered Pompey while both sides were on the march. The engagement was sharp, vicious and quite decisive; Carrinas stayed only long enough to see that he stood no chance to win, then beat a hasty retreat with his men reasonably intact-and greater respect. for The Butcher's son. (...)

Lucius Junius Brutus Damasippus, brother of Pompey Strabo's old friend and senior legate, tried to ambush the son in a small section of rugged country between Saepinum and Sirpium. Pompey's overweening confidence in his ability seemed not to be misplaced; his scouts discovered where Brutus Damasippus and his two legions were concealed, and it was Pompey who fell upon Brutus Damasippus without warning. Several hundred of Brutus Damasippus's men died before he managed to extricate himself from a difficult position, and fled in the direction of Bovianum.

The preceding paragraphs are found on page 25 of Fortune's Favorites, a work of stunning historical narrative by Colleen McCullough. This wonderful text (the third in a series of six - but sadly no more; she has proved herself quite prolific and knowledgeable) concerns in part, the return, rule and eventual demise of Sulla; the ascendancy of Pompeius Magnus and the development of arguably, the most intriguing figure in Ancient History, Gains Julius Caesar. Life in Rome, the boni and the intrigue within the Senate and the courts, Cicero, and the Slave Rebellion of the Spartacanii are just a few more themes woven into the rich fabric of her story line. Of course, this - I even hesitate to call it a synopsis - does not even begin to do justice to the depth of the work.

And of course, it is not at all my intention to review this specific text. However, I would and do completely recommend her books to any enthusiast of Ancient Rome. My intention is simply this: to describe how these two paragraphs started the "creative" juices flowing, to detail the processes involved in adapting these paragraphs to the wargame "table," and, as per usual, providing a report of the miniature battle that transpired.

ADAPTATION & PREPARATION

At the end of my last article, I remarked that I was interested in trying my hand at a contest taking place during the Roman Civil War . Specifically, a battle described in another McCullough text, wherein Pompey Strabo (father to Pompey the Great) faced a more numerous force of Picentes (Italians - this Civil War was based on the idea of citizenship for nonRoman Italian tribes of the country). Though the current project changes the parameters of the original idea, it is still a project based on Civil War (or Social War, for those readers more particular about titles) in Rome around 83-82 B.C. Instead of Roman v. Italian however, this internal strife pits Roman against Roman, legion against legion.

The cited paragraphs relate Pompey's sharp victory over two separate anti-Sulla forces. Though interesting in and of themselves, I must confess to being a little "shy" with respect to the nature of the terrain described as well as to the settings for the engagements. Being a solo wargamer primarily, I am not quite certain how one would effect or replicate an ambush on the table. I mean, really, I know where both forces are and any surprise on the part of ambushed player (me) would have to be faked. But anyway.

I was attracted to the idea of two opposing forces meeting on the march. And so, that will serve as the general basis of this fictional scenario. Given the dominance of Pompey in the described contests, I thought it might make things a little more interesting if the anti-Sulla forces had been able to combine before seeking battle. Pompey's three legions of veteran soldiers would now be outnumbered. Even so, the combined forces would "pay" in terms of their experience and what may be expressed as "presumptive problems" between the two commanders. This is not to suggest that Carrinas and Brutus despised one another, but simply to remark that each probably cared more for his own life and that of his men than for the other commander and his legions. And so, the general stage is set: it is to be a meeting engagement and Pompey's troops, while better in class, are fewer in number. Pompey has the goal of marching from one end of the board to the other (on his way to join Sulla) while keeping his force intact. The confederates opposing him have similar objectives. While they should reach the other end of the field, they should also prevent and disrupt Pompey's advance.

It is somewhat difficult to completely separate the adaptation of these paragraphs from preparation and planning. In the main, I used the provided order of battle in Mr. Avery's Vis Bellica rules for an Augustan Roman force to get a general idea of what the unit compositions and rosters should look like. On pages 12-13 of these same rules, Mr. Avery presents an "example" of the century of the legion, based on figure scale. To be perfectly honest, I had some trouble accepting the "manipulation" of the legion organization (no slight to Mr. Avery nor pun intended) so as to fit on the Vis Bellica bases. In brief, Mr. Avery allows a cohort to be at 6 figures, with each figure representing 60-85 men, formed 8-10 wide and 6-10 deep. (12) At the minimum then, a cohort would be 360 men. At "full strength," a cohort would take the field with some 510 men. Now, this seems just fine and is not refuted by other sources consulted. (See Note 1 please.) However, Mr. Avery then posits that a base or Roman infantry in Vis Bellica would equal two cohorts, in line next to each other. He goes on: "Five bases could therefore approximately represent the main body of the legion itself: the first (double strength) cohort being one base, the other bases representing two cohorts each." (12) The "missing" cohort is explained away as camp guards, reinforcements and the like. (13)

Looking through the text of the chapter on Marius and Sulla in WARFARE in the CLASSICAL WORLD, I find: that while the classifications of Hastati, Principes and Triarii were abolished, and while the long spear of the reserve infantry was replaced by the general purpose pilum, the flexibility of the legion was maintained. (133-155; schematic on 155 especially) I don't think the flexibility is truly represented by Mr. Avery. To be certain, five bases of Romans allows a greater degree of flexibility with respect to formation and maneuver elements, but it doesn't really hold against historical record. If it is accepted that the Romans maintained the three-line deployment of the legion for battle, then this is more easily and correctly portrayed with bases representing three cohorts in line, in addition to the one doublestrength cohort. Four bases then, would allow the legion to deploy with four cohorts in the first line (to include the double-strength or 1st Cohort), and three cohorts - one base - in the successive lines. For a two-line deployment, one could place two bases in front (six cohorts)

A little juggling of the numbers was required to effect this distribution, but I do think I have solved the "problem" of representation to my satisfaction. For this particular scenario then, the legions consist of four bases. Three of these bases represent three cohorts in line; each cohort of 5 figures; each cohort numbering some 425 men at full complement - 1275 for the entire base. One base of the legion represents the double-cohort, the 1st Cohort at 10 figures (850 men at full strength). At the higher end then, using Mr. Avery's scale and my "arrangement," a legion would take the field with some 4,675 men.

Returning just for a moment to the McCullough text, Pompey's force numbered three legions of "hoary" veterans, approximately 18,000 men. This divides evenly into 6,000 men per legion. In this present adaptation however, Pompey's legions and those of the anti-Sulla forces will each number a uniform 4,675 soldiers. This gives Pompey a total of just over 14,000 legionaries. The difference will be made up by auxiliary units. But I get a little a head of myself. This subject matter is better left for consideration in the orders of battle. Before looking at the force composition of each side however, let me again be clear that I was not necessarily finding fault with Mr. Avery's rules or explanation of how he represents the Roman Legion. I was simply pointing out that I have elected to pursue a slightly different representation of this formidable fighting unit.

ORDERS OF BATTLE

Given the historical (fictional narrative) parameters of this scenario, some minor adjustments had to be made as well with regard to command structure. In section 3.1 of his well-written rules, Mr. Avery details the four levels of command. Pompey's force, as described above, numbers three legions plus attached auxiliary units. For sake of simplicity, these additional units were combined into a separate "legion." In brief then, these legions constitute four "brigades," with each brigade under the direct command/control of a leader element.

Normally, the next higher level in the Avery command structure is Sub-General (one who controls 2-6 leaders). Accepting that this grouping of veteran rankers comprises an army, one can I think, safely and accurately name Pompey as General (the next higher level of command). Additionally, it will be noted that all commanders for each side have been assigned a command modifier. There are no rules governing this kind of rating in the general rules, but the topic has been discussed and debated on the Vis Bellica web site. (It is not an official amendment, but again, just an option for more "daring" gamers.) Without further tangential discussion then, let me present the opposing forces: the legions of Pompey Magnus first.

FORCES OF POMPEY MAGNUS (PRO-SULLA)

- Map ID Description

P Pompeius Magnus (General, +3 modifier)

A Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with +1 modifier -bases are CO/VET/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -1 base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

B Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with 0 modifier -bases are CO/VET/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -I base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

C Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with +1 modifier -bases are CO/VET/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -I base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

D "Legion": consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with +1 modifier -bases are mixes in troop type and weapons

-1 base at 8 strength points; OO/VET/MC armed with LA/smSH and SA

-1 base at 10 strength points; OO/AVG/MI armed with BOW/SA

-1 base at 10 strength points; OO/AVG/MI armed with LS/SH and SA

-1 base at 10 strength pointOO/AVG/LI armed with LS/smSH and SA

Notes on forces of Pompey Magnus:

1. Troop classification and weapon descriptions should be fairly self-explanatory. That is to remark, 00 refers to Open Order; VET means Veteran; SH stands for Shield while smSH represents Small Shield. (The Avery rules provide a -4 modifier for SH troops in combat; it seems plausible to cut this modifier in half for troops "armed" with small shields.)

2. As related previously, each legion numbers 4,675 men. With each figure or strength point representing some 60-85 men, the "legion" of auxiliaries adds up to approximately: 480 horse and 1800 other infantry. If the higher end of the scale is used, then these figures climb to roughly 680 cavalry and 2,550 other infantry. If this same scale is used to determine the total in Pompey's small army, one arrives at a figure of 17,255 men under arms. This is very close to the number provided in the McCullough text.

ANTI-SULLA FORCES

- Map ID Description

C Gains Carrinas (Sub-General, 0 modifier)

1 Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with 0 modifier -bases are CO/AVG/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -1 base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

2 Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with 0 modifier -bases are CO/AVG/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -1 base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

3 Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with -1 modifier -bases are CO/AVG/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -1 base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

4 Legion: consisting of 4 bases, commanded by leader with +1 modifier -bases are CO/AVG/HI armed with HW/SH and SA -1 base at 10 strength points; 3 bases at 15 strength points

5 Auxiliary Legion: consisting of 5 bases, commanded by leader with 0 modifier

-bases are mixed in troop type and weapons

-1 base at 12 strength points; OO/AVG/MC armed with LA/smSH and SA

-1 base at 10 strength points; OO/AVG/LI armed with BOW/SA

-1 base at 10 strength points; OO/AVG/MI armed with LS/SH and SA -1 base at 10 strength points; OO/AVG/LI armed with LS/SH and SA

-1 base at 10 strength points; OO/AVG/LI armed with LS/smSH and SA

Notes on forces of Pompey Magnus:

1. As suggested, each Sub-General commands two legions and so, overall command is "shared." Brutus also holds command of the auxiliaries.

2. Applying similar scale math to the anti-Sulla forces, one arrives at the following figures:

- each legion @ 4,675

auxiliaries @ 4,420 (1,020 of these being horsemen)

Total of anti-Sulla "army" is: 23,120 men and horses

This puts Pompey at something of a numerical disadvantage, but again, his legion units are classed as veterans and he does enjoy a significant leadership modifier.

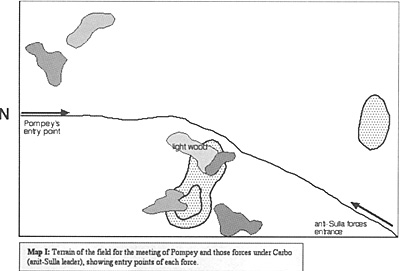

TERRAIN

In contrast to the terrain lay out for the Norman v. "Saxon" contest previously reported, the battlefield for this wargame was relatively simple. (Please see Map 1) This fictional plain in central Italy contained no coursing river or other water obstacle. Instead, a road (the Via Crissus'?) ran from north to the southwest corner of the table. The battlefield was flat with the exception of a small one tier hill at the very south edge, and a larger, two-tiered hill on the west side - approximately halfway between the northern and southern entrance points. Under the Avery rules, both hills were designated to have gentle slopes and thus be classed as "rough" terrain. (Not very good for close order troops, but agreeable to the lighter and more flexible kind.) In a northern corner of the field, there were a couple of wooded areas - perhaps one a wild olive grove? Both of these copses were designated to be thick and accordingly, classed as "difficult" terrain.

The large, two-tiered hill was fairly wooded; the eastern most tree line being designated light and so "rough" by the Avery definitions. The other three woods fell more or less into the range of heavier cover, and thus were classed as "difficult" terrain, interfering with movement as well as visibility. The rest of the table was classified as open terrain.

RULE CONSIDERATIONS

This being just my second attempt at a wargame with Vis Bellica, I will again claim a degree of inexperience though certainly not deny responsibility with respect to what follows. As with my first scenario, I have opted to eliminate most of the pre-game phase as outline on pages 24-27 of Mr. Avery's booklet. The exceptions of course, would be 6.4 Initial Orders and the subsection of 6.4.1 Orders.

The idea of the wargame is to have two forces meet and fight from their respective routes of march. As Ms. McCullough described: "...and encountered Pompey while both sides were on the march." (25) Initial orders then, are simply these: to march in this direction or that direction, as determined by the side the legions are on. It gets a little "tricky" with regard to orders for the tactical units, however. Mr. Avery establishes orders of four (4) kinds: Attack - self explanatory; Hold - only for missile troops; Hold - again, self-explanatory; and, Retreat - once more, an obvious order. There is no March order. While the Attack order may be taken as encompassing this order of movement, I find it to be specifically offensive in nature and design. Therefore, for purposes of this scenario I am creating a fifth kind of order: the March order. Any kind of unit can be given this order and as is apparent, the primary concern here is one of movement. Combat-readiness will be secondary, the troops under this order being in traveling formation, carrying arms and shields for ease of march and not at the ready. In warmer circumstances, one might well imagine that the legionary infantry will have their helmets off and shields strapped over their backs.

Under the Avery rules, leaders and other officers must expend command points in order to change orders of units as well as rally them underadverse circumstances. The same principle will apply here then, for transforming units under March orders to any other order. While it would appear sensible that troops don't just keep marching into the waiting ranks of a formed enemy, one of the strong points of Mr. Avery's publication is just that: removing a certain amount of control from the player. I must admit as well, to thinking about penalizing units that moved immediately from March to Attack, for example, but this seemed rather severe and cumbersome.

Indeed, given the training of the Roman legion, this kind of transformation would have been performed as naturally as taking a breath.

As a final point of contrast with regard to my first scenario play test of these rules, I decided that the nature of the wargame as well as terrain required the use of the spotting rules. This process takes place in the Command Phase of the Turn Sequence, and is outlined fully on pages 33-34 of the rules.

Though it adds to the amount of material to be digested and remembered, the latest version of the amendments were taken from the web site, printed and set within easy reach of dice, rulers and "figures."

ROUTE OF MARCH

ROUTE OF MARCH

Gaius Carrinas rode his horse in silence. Directly to his front, the first of his two legions marched with all the quiet expected from a formation of some 5,000 armed men. Not that stealth was a concern on this fine, warm morning. The message from Carbo still weighed on his mind and its meaning was only interrupted if at all, by the comings and goings of a number of legates and couriers riding up and down the column. Carbo had enjoined Gaius and his compatriot Brutus -for that's what these men were, patriots to Rome against usurpers like Sulla and his lackey, Pompey - to find and prevent or better, destroy, those legions marching with Pompey, and thereby wreck Sulla's plan ... thereby save Rome, really. Though a brave enough man and one who had seen battle prior to this assignment, deep down, Gaius Carrinas wondered if he could stand up to Pompey. Brutus Damasippus, in contrast had no such qualms about his ability. He was in command of his feelings as well as of the two legions - plus auxiliaries - that marched behind Gaius. And, he was quite looking forward to the challenge of meeting Pompey on the field.

At this same time, Pompey was astride his mount and following his first legion along the Via Crissus. Unlike Gains or Brutus, he had not received any message nor courier from the camp of Sulla. Pompey did however, have a very good idea of the theater where the "renegade consul" was operating. Confident in his abilities (the hard lessons had been learned in Nearer Spain against Sertorius) and in those of his veteran legionaries, Pompey left the details of the march to his subordinates. His mind was more on the meeting to take place between himself and Sulla. On this summer morning, Pompey imagined what that meeting would be like; what the topic or topics of conversation would be; how he might he treated or regarded by Sulla; what history would say about the two; even down to the detail of what he himself should wear for the occasion.

Of a sudden, drums and horns sounded from the ranks of the legion to his front. Shaken from his revelry, Pompey noticed that the legion to his front was shaking out into battle order on the road, and that there was a courier galloping toward the command group with all haste. Pompey halted his horse and took a deep breath ... it looked like there would be a battle to fight and of course, win, before he would meet with Sulla face-to face, one Great Man to another.

FIRST CONTACT

In Vis Bellica, the game move sequence is divided into three sub-phases. Command rolls, distribution of points and spotting procedures take place in the second sub-phase. In the third sub-phase, normal movement takes place. In this particular scenario however, some "liberty" had to be take with the order during game turn three.

Pompey's leading legion had reached the eastern edge of the hill and the leading legion of Carrinas's command was fast approaching the same point. To allow each to move its full movement on the road, would have brought the legions into an unrealistic (my assessment) proximity. It seemed more practical / realistic to me to roll for spotting at the time and distance that the leader bases of each legion had an unobstructed view of the field (the hill and woods were not in the way). Further, it seemed practical / realistic to allow each leader to try to deploy his force at this point as well as communicate the finding along the rest of the column.

At the conclusion of a modified turn three then, Gaius Carrinas had deployed his first legion in line to the right of the Via Crissus. Aware of the presence of Pompey but not within sight, the trailing leader "bases" continued to march along the road. Carrinas formulated an initial plan of action and without consulting Brutus: he would fight Pompey using the Via as his left flank, and concentrate his effort on the open plain east of the wooded and sloping hill.

Pompey, though respecting that he must meet force with force and so, deployed his first legion to mirror the enemy one opposite, had other ideas about how this battle might develop. Issuing orders with his usual flair, the legates were off and riding to the trailing legions. In short order, the auxiliaries had turned southwest off the Via Crissus and were making for the rough ground on the wooded hill. Behind them, the legions stepped up their rate of march. As with the anti-Sulla forces, none of these legions had been detected. (The Vis Bellica rules do provide for a false or dummy leader base - and so, the opposing player cannot quite be sure.) Pompey's plan was formed "on the spur of the moment" as well: the enemy center would be held and then smashed at the same time the auxiliary units swept off the hill and into their left flank and rear. As it turned out, the maxim held true for both commanders: no battle plan, even those just made apparently, lasts once contact is in fact, made with the enemy.

The Vis Bellica move sequence orders that leader bases (those units not yet spotted) move and maneuver prior to the deployed units. This caused a little problem for Gaius Carrinas as he was forced to turn his second legion to the right for lack of space behind the first, deployed legion. The other half of the anti-Sulla force, in addition to Carrinas's detouring legion was soon forced to deploy anyway, as Pompey's auxiliary legion quickly gained the crest of the hill on the west edge of the field and was able to see the host arrayed before them. The commander of the auxiliary cohorts dispatched two riders to inform Pompey and in the next instant, drew his cavalry sword and ordered his medium cavalry to charge into the column of enemy. Angling for the left-front of the first collection of units, these medium cavalry were soon met by a countercharging and more numerous force of light cavalry. Melee was joined and Pompey's horse fought courageously, but were as mentioned, outnumbered. They did inflict as much punishment as they took, but their commanding officer was already off his mount and the legion commander had sustained a nasty cut on his bridle hand. However decimated, these men continued to fight.

East of this raging combat, Pompey launched his first legion against the front line of Carrina's formation. Though these men were not as experienced as Pompey's soldiers, they knew better than to stand and wait for the shower of pila and sting of short sword. At first, the opposing lines were in the shape of a "V," but as each cohort charged in and entered the melee, the opened end of the "V" closed. Volley of pila was followed by volley of pila and then it was the sword. It was bloody work, but Pompey's legion forced the opposition back. On the right of line, the 1st Cohort succeeded in breaking its counterpart in the enemy line, and routed them. On the left of the line though, the anti-Sulla infantry fought gamely, matching Pompey's veterans blow for blow and thrust for thrust.

But again, it was bloody work: in the space of a few minutes, something like 3,000 men were dead, in the process of dying or wounded to one degree or another. (Melees can be rather "decisive" - did not want to use the word "bloody" again - in Vis Bellica. Adding up the modifiers for the cohorts of Pompey, one finds: initial strength of 15 plus modifiers of +3 for charging, +3 for veteran troops, +6 for HW at first contact, -7 for total defending troops modifiers (shield and weight of infantry), yields a pre-combat die roll of 20. per the rules, one strength point is removed for each factor of 5, so the anti-Sulla cohorts were losing 4 "figures" right from the start.) Of these, approximately 1,700 were from the first legion of Carrinas's two legion force. One cohort was in rout and one had been shaken; all were in disorder as a result of the rough handling.

Though also in disorder, Pompey's men followed up their local victories. It was only on the left end of the line that things had not been decided in that first contact. Pompey - viewing the melee from about 200 yards - remained confident about the outcome of this first combat, however. His other two legions were coming up along the Via Crissus at the double, and he turned his attention to their deployment.

Brutus Damasippus, caught a little unprepared by the sudden appearance of enemy horse to his left and front, ordered his part of the column to halt until he could get a better grasp of the situation. He even considered riding up to confer with Gaius, but the sound of the infantry battle to the front of the column and the subsequent appearance of fleeing survivors, suggested that Gaius already had his hands full. Brutus turned to one of his junior tribunes and issued a stream of orders.

A NARROW ESCAPE FOR GAIUS CARRINAS

As if the numbers were not already to their disadvantage, the veteran horsemen of Pompey's auxiliary legion found themselves attacked by another unit under Brutus's command. Their officer in front, unit of light spear men joined the fray. It was simply too much to take; Pompey's cavalry - very much reduced - broke and fled back toward the hill. This took them through the waiting lines of their supports (too little and too late) of light and medium spear men as well as a unit of bowmen who remained on forward part of the slope. The commander of the anti-Sulla auxiliary legion then ordered the rest of his units to turn out from the road column, and prepare for action against this thin line. Though in open order, this sudden shift in direction caused some disorder in the ranks. Fortunately however, the move also took them out of the way of the routing legionaries (from the first clash with Pompey's leading infantry) as well as cleared the road for the main force of Brutus.

Another cohort from the first anti-Sulla legion broke under the strain of combat with the veteran foot and ran despite the pleas then curses of both legion command and Carrinas. It did not get any better for these troops: the other two cohorts still engaged were being cut down and both were shaken as a result. These men tried to respond in kind, but Pompey's veteran legionaries had recovered from the losses of the initial shock and were proceeding with the melee and subsequent advance in an almost machinelike manner.

Unlike Pompey the Great, who had seen to it that his other legions were deployed in line and marking time until called to advance and support the success of the lead units, Carrinas and Brutus had no such foresight. To be sure, Gaius might have thought he could swing around to the left of Pompey's line, but that was based on the assumption that Gaius would have a front line on which to maneuver. With regard to the cohorts under Brutus, well, as remarked, the cavalry action had produced a halt in their march and until the order to resume was received, this is where they stood.

In the command portion/phase of the subsequent turn, two cohorts of Pompey's first legion were reorganized and then were charged into the backs of fleeing survivors of the initial melee. These anti-Sulla men had no chance: outnumbered by a large margin and attacked from the rear, they were cut down to the last. (3) Their legion commander, caught in the flight, was killed as well. Gaius Carrinas (C), in the path of the charging legionaries, escaped to a temporary position further in the rear, but had been given quite a scare.

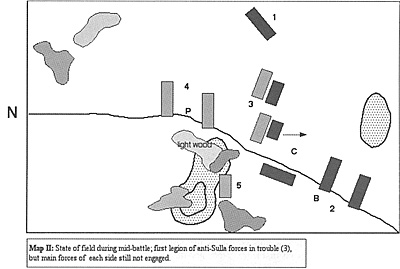

The action being so developed, the remaining anti-Sulla legion commanders decided to deploy their men into line and hope that numbers would in fact, be the deciding factor on this field. True, one legion had for all intents and purposes, been taken out of the fight, but it was at a price for Pompey. The advantage still lay with the confederates. The second legion of Carrinas's small force switched from column of march to line then, and prepared to meet the second legion of Pompey's force. (1) This second legion had drawn up just east of the end of the hill and light wood. Pompey the Great and his third and last legion of veterans were ranged some 400 yards to their rear. (P and 4) Back down on the Via Crissus, Brutus (B) ordered his legions to change formation as well. In a matter of minutes, these heavy infantry formed into line, basing off the First Cohort which remained on the paved-stone road. (2)

To the left front of these formations, the auxiliary units under Brutus's command prepared to engage their opposite numbers. Pompey's commander, having given up any hope of rallying what little was left of his cavalry force, concentrated on strengthening the line of light and medium infantry on the south facing of the hill. (5) On the slope behind these open order lines, archers loosed long range fire into the ranks of organizing cavalry and light infantry. A few score horsemen were brought down, but the troopers shook off these casualties. They would exact revenge with the order to charge that was surely to come. (Please see Map II for state of the field at this juncture.)

SET BACK ON THE LEFT, THEN IN THE CENTER

Instead of engaging Pompey's second legion, the as yet engaged legion of Carrinas's command took advantage of its location and of the fact that Pompey's second had not closed up yet. Two cohorts from this fresh but not veteran legion waded into the ongoing melee to their front, taking the enemy in the flank. This was too much for the veteran rankers, and they were routed, leaving some 800 men on the ground. The survivors fled through the approaching ranks of Pompey's second legion (too late) but morale rolls all around were satisfactory. The path of the rout would take these beaten men directly into Pompey's command circle, so both commanders of the front line legions decided he could restore order to these depleted ranks. On the far left of this shifting melee, one cohort of Pompey's second legion was able to reach the enemy line. Here, they charged into the First Cohort and reduced it by half through accurate pila volleys and work with the sword. As with earlier fights in the day, the push back did not come without cost. And the restoration of order on this flank would take a little time.

Map II: State of field doting mid-battle, fast legion of anti-Sulla forces in trouble (3), but main forces of each side still not engaged

Map II: State of field doting mid-battle, fast legion of anti-Sulla forces in trouble (3), but main forces of each side still not engaged

A bird's eye view showed that just three units of veterans faced six units of anti-Sulla rankers. (Based on the orders of battle and organizational notes, this works out to approximately 9 cohorts versus 15.) Just to the west of this battle, Pompey's first legion had four under strength cohorts in a line facing the legions under Brutus Damasippus.

While the heavy infantry crashed into each other on the east end of the field, the commander of Brutus's auxiliaries launched a coordinated assault against the hill. Instead of throwing in with his depleted light cavalry (still recovering from their contest with Pompey's auxiliary horse), light and medium spear men rushed the lines posted at the base of the hill. Here, Pompey's commander made the mistake of receiving this charge at the halt. Though his men fought gamely and took several score anti-Sulla soldiers down with spear thrust and sword cut, they were over matched and pushed back to the very edge of the hill. The archers to their rear could not offer any real support, but looked to become involved in the contest soon, whether they wanted to or not.

In the meanwhile, Brutus Damasippus advanced his legions in line up the Via Crissus, but did not engage the enemy. In fact, on getting close to the action, he ordered his men to halt and hold in place. This, much to the consternation of Gaius Carrinas, who galloped across the front of these immobile legions and let Brutus know. The response? Brutus simply looked at the general and asked him why he wasn't in the thick of the fight with his own men.

The situation on that flank had been somewhat restored. At least it had been with respect to Pompey's purpose. The routing cohorts had run through the ranks of his third and last legion, disordering one unit. However, this unit kept on pace and advanced with the rest of the legion when the signal was given. The other half of the first legion (diminished in strength for the first fighting, it will be recalled), under direct control of their commander, drew up in a tight line across the Via Crissus. They did not turn east to join the involved melee, but held in place, a small counter to Brutus's force that was also holding in place along the same stretch of improved road.

The continuation of the combat was left to the ranks of the second legion of Pompey. Though outnumbered, these men were not outclassed and they warmed to the task at hand. Casualties mounted in the ranks of the anti-Sulla legion, but they fought on - matching the veterans or slowly yielding ground but not breaking. Still, it has to be remarked that this line was in quite a state of disarray, and would probably not hold if Pompey threw in his third legion. It also has to be remarked that this was not an easy decision for Pompey, given that two fresh legions remained within potential striking distance.

Back on the wooded hillside, the auxiliary combat continued. Here, the anti-Sulla forces worked to push back the light and medium infantry to their front, but simply could not break the formations. (The bowmen on Pompey's side were still not involved, but any moment now.) Tiring of this stalemate, the leader of Brutus's auxiliary legion (Decimus, perhaps?) ordered what remained of his cavalry into the melee. He also sent word that the two units lagging in the rear should move up and prepare to join the fight.

Seeing as how engaged were Pompey's men to his right front and seeing as how so few stood between his own forces and a certain advance up the Via Crissus, Brutus - paying no heed to the continued ranting of Gaius Carrinas - order his front line legion to advance. Though the veteran rankers blooded these untried troops, the numbers were just too great to resist. The remaining half of Pompey's first legion broke and fled into the right side of his third. In addition to losing quite a number of heavy infantry, the legion commander was felled during the subsequent crush of fugitives. Disheartening as this was to Pompey, his legionnaires endured the brief disturbance and steeled themselves for the coming contest. The other end of this reserve line was disrupted as well, for a unit of the second legion had been taken in the flank while desperately engaged from the front. Though these men had been rescued by a flank attack launched by a friendly unit, the damage had been done and their spirit broken for the present time. Once more, morale checks were made and the veterans of the third legion held firm. As for the second legion - the one engaged by Carrinas's men in his notable absence - these men were hard pressed as well. Steady fighting had finally routed the cohorts on the far right of the anti-Sulla line, and the middle of the line was in just as much disorder. They still maintained a distinct advantage in numbers, however.

While all this was taking place, Brutus's commander of auxiliaries was having a "tough time" throwing Pompey's light and medium troops off the hill. He (Decimus, yes this will do) had still not got his other units into a good position: the nature of the terrain and the space taken by those units already fighting did not allow full deployment. And what is more, his troops had to fight uphill. On the left or west of this line of battle then, his troops were still engaged. But on the right of the line, even with support of the cavalry, the effort had been pushed back with some loss. Pompey's spear men and supporting bowmen, though shaken as a result of the hard-fought melee, did not release their hold on the heights.

Pompey the Great was not in the middle of the action just yet, but he was close enough to see what was developing. One of his three legions was out of the fight and another was heavily engaged but doing well enough. This left just one, some 5,000 men, to face the whole of Damasippus's force plus whatever might be left and still capable of combat from Gaius's command. His thought process did not even begin to consider the status of the battle for the hill and woods, as this was quite removed from the clash of the heavy infantry. Light horse and archers maybe a nuisance, but they were not the kind of troops with which one could take and hold ground. The experience in Spain had taught him much. Pompey shouted for two of his tribunes, issued several orders and then prepared to gallop to the front of his third legion, in order to lead these fine men into the fight.

POMPEY VERSUS BRUTUS

On his way to the front, Pompey took a few minutes to harangue and cajole the routing elements of cohorts that had been thrown back by the combined efforts of Carrinas and Damasippus. Sufficiently chastised and renewed in heart, these men rallied well behind the fighting. Pompey hoped that they would soon rejoin the contest, but wondered what real effect their decreased numbers would provide.

His plan to gallop to the front and lead his men was disrupted by the sudden charge of Brutus's first legion. Not wishing to endure this attack from the halt, the men of Pompey's third legion turned slightly to the right and commenced their own charge. The roar from several thousands of throats was soon drowned out by the clang of sword against sword and sword against shield, as well as by the screams of the wounded and dying. Three of the four units (stands) in Brutus's first legion took something of a beating, and were pushed back by the more capable veteran rankers. In fact, in the double-strength First Cohort of the anti-Sulla legion, half of the men were cut down and the rest routed away. Caught up in the swift and bloody melee, the legion commander went down with two pila in his side.

A similar demise took place on the other side of the general contest between the legion infantry. Over on the eastern flank of this section of field, another anti-Sulla legion commander was felled. He had advanced his men onto the inviting flank of a couple of occupied enemy cohorts and was making some progress, when his men were countered by the charge of a strong and reordered cohort. Though this charge was eventually repulsed, it was not without some loss and again, at the price of a general officer.

The anti-Sulla forces were not the only side to suffer the loss of a leader at this stage of the battle, however. In the center of the massed melee, Gaius Carrinas (perhaps redeeming himself slightly) had restored a shaken unit to some use and directed it into an ongoing fight. Once again, the Pompey cohorts were caught on an exposed flank and were, quite literally, rolled up with terrific loss. Not one man was left standing: the attached legion commander going down with several sword thrusts, but not before taking at least three enemy with him.

As a result of this, Pompey effectively had no center. His third and last legion was completely engaged with the men of Brutus's first line, and two units were still fighting on the left flank. The Roman commander was able to locate three fresh cohorts (men who had not been able to make the charge with the rest of the third legion) and hold on to these men as a kind of reserve, but that was it. He and his men were being sorely tested. Even if he did break through that first legion under Lucius Brutus, there was another of some 5,000 men waiting. The again, he had to contend with a mix of units in the center and left of his line.

While the situation in the center of the field approached resolution, the action on Pompey's right flank continued. Once more, Brutus's auxiliary commander launched his men up onto the hill. And once again, they were met and held by the thinning ranks of light and medium infantry. It was perhaps as much a problem with terrain as it was with poor rolling of the dice on this side of the battlefield. Even with an edge in numbers, Decimus could not shift the contest in his favor.

His poor luck continued as the fighting progressed, the friendly-to-Sulla bowmen finally getting into the thick of it. Though unshielded, these bowmen wore mail shirts and possessed helmets as well as short swords. They waded into the depleted ranks of the enemy light spear men and threw them back off the hillside. Next, they changed weapons and launched a volley of arrows into the few horsemen arrayed in support of these spear men. They too, were sent away in defeat. In the space of a few minutes then, Brutus's auxiliary commander witnessed half of his "legion" rout. By way of comparison, routing would have been a more favorable outcome for the hard-pressed men left in Carrinas's legions.

Over on the right of the anti-Sulla line, Gaius Carrinas watched, helpless, as two units from his second legion were rolled over by heavy infantry under the direct control of Pompey. The men of Pompey's third legion had succeeded in pushing back Brutus's men again; inflicting more casualties as the melee continued. Taking advantage of disorder in Carrinas's line, Pompey attached himself to a unit of veteran rankers and led the three cohorts at a charge. The defenders were overwhelmed to the last, but did manage to loose a weak volley of pila against their conquerors. Stepping over the remains of the one line, Pompey's soldiers quickly brought action against those waiting in the reserve. Carrinas himself, separated from this contest, but seeing it develop negatively, attached himself to a few cohorts from Brutus's first legion. Farther up the line, a similar situation was played out. This time, what was left of two anti-Sulla cohorts threw themselves in the way of a charge by four times their number, in order to prevent a flank attack. While this sacrifice did slow down and disorder the legionnaires from completing the flanking maneuver, it did not prevent the elimination of the exposed unit. As related above, this unit was simply "swallowed up" by superior numbers. Though at some cost, it appeared that the fight had finally shifted in favor of Pompey and his troops on this part of the field.

Indeed, as the sun began its early afternoon course in the sky, Fortune favored Pompey and his men. On the far left of the line, the outflanked cohorts of Carrinas finally succumbed and ran for their safety. In the center, the cohorts Pompey commanded met and exterminated the second line put quickly in place by Carrinas. To the right of this disaster for the anti-Sulla forces, another followed. Facing greater numbers and more experienced troops in the bargain, two units of Brutus's lead legion routed away after suffering more casualties. The fight had left these men; not a single ranker among the veteran legion infantry fell in this phase.

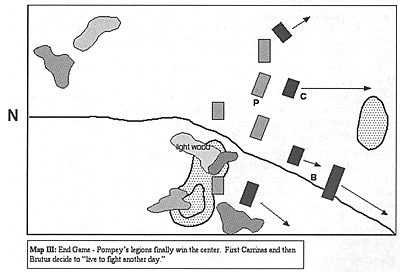

Gains Carrinas (C), now with just three cohorts on the field, decided that enough was enough. The order to retreat given to his subordinate, Carrinas trotted off the field well ahead of his what was left of his infantry. Brutus (B), posted in front of his remaining legion, witnessed the collapse of the main line. The few survivors were soon streaming past his command suite - paying no attention to the general. Shortly after Carrinas gave his final orders, Brutus too, issued the command to retreat. A rider and message was sent to the auxiliary legion as well. Unlike Carrinas, Brutus Damasippus marched off the field with his legion ... with his men. (Please see Map III, showing state of field.)

Greatly fatigued and quite less in number, Pompey's legions let their enemy leave the field. In no condition to continue the march south, the blooded cohorts were reorganized, and set to clearing a site for a well-fortified camp.

COMMENTARY

In the McCullough narrative, Pompey easily handles the "armies" sent against him by Carbo and a worried Senate. In each short and sharp engagement however, Pompey outnumbers the enemy; not by a huge margin but at 3:2, with veterans versus non-veteran troops. This is a definite advantage. When factoring in the leadership qualities of Pompey, well ... As related before, the McCullough story line was revised to make the wargame larger as well as a little more simple (avoiding the inherent difficulties of reconstructing an ambush within a solo re-fight).

On general review, it seems that this revision, while making things simpler overall, did not make the battle any more easy for Pompey the Great and his veteran legion infantry. In fact, a quick comparison of casualty figures will show the victory was a Pyrrhic one.

Of the original 165 "points" in Pompey's three legions, 94 were counted as lost when the battle closed. Translated into Vis Bellica higher-end scale, this amounts to approximately 8,000 legionnaires or, roughly 56% of his standing force. With respect to his auxiliary forces, 7 cavalry "points" were listed as lost and 17 "points" of light or medium infantry would not be among the ranks when the army formed for march the following day. In addition to these significant numbers, Pompey suffered the loss of two legion commanders in the hard fought contest.

Turning to the other side of the field, the numbers of casualties are just as horrific. A grand total of 127 "points" were lost in the anti-Sulla legions. Using the scale referenced above, this calculates to nearly 11,000 men. Interestingly, this figure works out to represent a very similar percentage with respect to legion infantry engaged - (57% percent versus 56% for Pompey). In the struggle over on the hill, Brutus's auxiliaries lost some 10 cavalry "points" and another 15 infantry "points." More damaging for Brutus and Gaius perhaps, was the loss of three legion officers.

Map III: End Game - Pompey's legions finally win the center, First Canines and then Brutus decide to "live to fight another day."

Map III: End Game - Pompey's legions finally win the center, First Canines and then Brutus decide to "live to fight another day."

A very roughly figured sum, puts the number of dead, wounded and missing for both sides at about 21,000 men - of all arms and types. While not altogether that unusual a total for an ancients battle, the high cost to the victorious side is noteworthy. One is almost driven to ask if these returns are a result of poor strategy, or the result of rule mechanics?

As this wargame was set up as a "meeting engagement," I don't believe that strategy really comes into consideration. That is to remark, each side had its legions in column of march and were proceeding up or down the fictional Via, and had no advance notice that they were on a collision course. Given the nature of the terrain, each command did what they could in getting legions from column to line and into battle. One could perhaps fault the anti-Sulla forces for not using their slight advantage in numbers to a tactical advantage. But again, given the constraints of the terrain and given the character of Gaius and Brutus, I think they acted within the "sense" afforded by the McCullough text.

Pompey "played" his auxiliaries well: securing the wooded hill line and then keeping an enemy from gaining the same or worse, breaking through and coming up on his rear. At the same time however, I'm tempted to wonder if the sub-battle over on Pompey's right was a wise move. That is to suggest that if the auxiliaries were a kind of "throw away" force, then why not put them out front to engage the enemy legions right off, while his main line got into fighting order. And by this, I mean not just one legion ready to go, but all three in line with perhaps a small reserve commanded by the Great Man himself?

With regard to the anti-Sulla forces, I think they were "bothered" by many of the same factors. Having more troops in column, it took the sub-generals and legion commanders a little longer to get these men into fighting formation. And again, the interplay between Gaius and Brutus did not really help the cause: each man was more concerned about his "army" as opposed to the whole force.

Looking at the auxiliary question from this side of the field, it occurs to me that Gaius and Brutus should have let Pompey take the hill line. This light force could have been "watched" by a small detachment from one of the legions. The rest of the heavy infantry could have been sent against Pompey's men - as they were in fact. However, with cavalry and light infantry coming down on the right flank and rear of Pompey's engaged veterans, the battle might have quickly turned in their favor.

Suggestions and the merits of same, may be argued back and forth (if only this, then this would have) with respect to the strategy used by both commands. However, when one considers the clash of heavy infantry in the open field, especially Roman heavy infantry, the allowance must be made for the probability of a very high casualty rate.

In a previous report, I had referenced the work of Professor Victor Davis Hanson with respect to the military might of Rome. His description and explanation centered on the "built-in" strength of Roman troops (the result of birth, geography, environment and training) against those kinds of enemy that could be labeled "uncivilized." The machinelike manner of the Roman legion is terrible to behold in text. I cannot begin to imagine what it may have been like to actually be on the other side of a battlefield where the legions were present. Given this "nature" and given this mode of fighting, a contest pitting trained, formed legion against trained, formed legion must have been even more terrible.

Ruminations about Professor Hanson's scholarship aside, the Vis Bellica rules do provide for some rather bloody melees. If one takes a unit from one of Pompey's legions, for example - this unit representing three cohorts of heavy infantry - one determines that right away, before any modifiers are applied or dice rolled, that a base strength of 15 points results in 3 casualties for the enemy force. (The total points - base strength plus modifiers plus dice roll are divided by a factor of 5 in order to determine total losses.)

Now, if the example is continued, we might find that these veteran soldiers (+3 modifier) are charging the (an) enemy unit, earning another +3 modifier. The legion infantry have the pila and short sword, so are rated very high on the "first contact" list: a +6 modifier. At this point, no dice have been rolled for casualties, but the figure stands at a factor of 27 or, divided by 5, a loss of 5 figures or strength points. If the attacking legionnaires have a leader attached and are perhaps making the assault against the flank of the enemy, then the modifiers only increase. In this particular wargame, cohort faced cohort and so each melee combat was modified "down" by a factor of -7 usually (-3 for the enemy being heavy infantry and -4 for the enemy having shields). Even so, first melees as a result of charging into the enemy were terrifically bloody / costly. If, to continue this example, the attacking cohorts are veterans and have a leader plus the flank advantage, the base strength plus modifiers works out to: 15 + 3 + 3 + 6 + 5 + 1 - 4 - 3 = 26. Before the dice are rolled, the enemy unit has "taken" 5 hits. To an opposite group of cohorts, this unit also 15 points in strength, this means that one-third of the unit is lost in that first contact and resolution. More, if the dice roll is on the high side.

My apologies to the reader for this perhaps extended example of the Vis Bellica melee process. The intention here, in addition to explaining the process (as I understand it) is to transition into a general discussion of the rules in total. In some sense, a review of rules demands a separate treatment. At the same time, what better point to "discuss" rule mechanics and processes than in a commentary? Admitting the contradiction, in a previous submission, I suggested that before one could make any decision about a rules set, one would need ideally, to "fight" three wargames with the rules. This fictitious Roman Civil War project marks just my second "experiment" with the Vis Bellica rules. For good or ill, it also marks my last "experiment."

Citing the Introduction to Rule Amendments for Vis Bellica from the web site:

- "No set of wargaming rules ever hit the streets perfect as no amount of play testing can ever really match the collected intellect of the wargames community. Vis Bellica is no different. Below you will find the "official" amendments to the rules."

Along this same line of thinking, one could just as correctly remark that, no one wargamer is perfect when it comes to comprehending and applying the processes and mechanics of a wargame rules set. While Vis Bellica is different than a number of rules (ancient or another period), given its updated amendments listing and the existence of an online group for discussion as well as questions and answers, I still had some difficulty in transferring rules from the page to practice or application on the wargames table. The following paragraphs then, should not be interpreted as complaints or the "finding of fault" with Vis Bellica, as they may be more indicative of that imperfect nature mentioned above. They may also just simply represent certain biases that I have accumulated and or unwittingly nurtured over some 20 years in this hobby.

The game move sequence as I believe I have mentioned (here or in the first wargame report), is divided into three larger segments or phases. In sub-phases, movement of units takes place at four different points and shooting takes place during three different points. While I do think the command phase, with leaders rolling to "control" their units and or receive command help from higher-echelon officers is a welcome adaptation of the DBA or DBM pip rolls, the process can become a little drawn out in larger games. This is especially true with regard to determining who moves first on each side and who moves first within the divisions of each side. It seems to me that the simpler approach of Movement, Missile (fire), Melee and Morale determination would speed the process along without any significant loss of "realism" or detail. In the application of K.I.S.S. principles then, four movement sub-phases are reduced to just one; three separate shooting sub-phases are reduced to just one phase of resolution as well.

The other aspect of the game move sequence that gave me pause for thought, was the end sub-phase of the third segment: the rolling for "officer casualties." In this sub-phase, each commander on each side has to roll a certain number of dice based on his (or her, if Queen Boudicca) distance from the nearest enemy base. The greater the distance from the enemy, the more six-sided dice to be thrown. If the dice come up as all 6's, then the commander in question has had an "accident" and an additional roll is made to determine how many command stand strength points are lost. As with the "objection" about the length and perceived complexity of the game move sequence, I believe I made passing mention at the "curiousness" of this aspect of the game turn.

What are the odds, that Sulla, sitting on his mule, wearing his broad-rimmed hat, well behind the front lines of the contest between his legions and the phalanx of foreign pikemen, would suddenly be "laid out" by a stray javelin, arrow or sling stone? Granted, the probability exists, but it is an extremely low probability. (Admittedly, this is perhaps well represented by the number of dice that have to roll up as 6's, but this is another sub-phase and more dice tossing that tends to slow down the game as a whole.) Why not simply make a provision only for the commanders attached to units that are in melee, or for those that are in range of enemy missile units? Command losses could then be determined in the melee and or missile phase. The effect(s) of these command losses would then be determined in the morale phase.

Fully one-third of the quick-reference player aid sheet is devoted to the combat modifiers that may or may not apply in the course of resolving a melee. While not overly taxing in and of itself, the melee process was a little confusing. (Again, I will stipulate to my lack of experience with these rules as well as to the statement that I am not a "perfect" wargamer.) Melees are fought/resolved in the first part of the game move sequence, but these are simply a continuation of the melee(s) which result from the charge phase (the first action in the third phase of the game move turn). My questions and of confusion stem from the following: first, if a unit involved in a melee is both disordered and shaken, which modifier applies? Do both modifiers apply, giving the poor unit a negative eight "total" before any other additions or subtractions are made? Second, how does one adjudicate instances where a base or unit will "charge" into an active melee?

In more detail: opposing units are facing one another and the melee results in a push-back of the defender but no rout. The attacking unit follows up and both units are marked as "disordered." In a subsequent charge phase, the "offensive" player charges a second unit or base into the contest. This unit does not land on a flank or rear of the enemy, but comes into the fight "through" the ranks of the already engaged friendly base. How is this handled?

To be certain, the discussion group at the yahoo site would probably offer a number of answers to this concern. But my point is, would it not be "easier" to have this kind of situation addressed in the pages of the rules? Would it not be "easier" as well, to have some sort of schematic that would explain this type of engagement in steps. (Here, I'm thinking of the simple line drawings that were found in DBA, or even, the more involved diagrams contained within the pages of Fire and Fury.) The quandary about which modifier to apply with respect to disorder or shaken status, lends itself in a manner, to further comment about the command rules and command effects. On a first reading of the rules, I was rather surprised by the "reach" of the commander-in-chief. According to the command/distance table, this gentleman - be he Roman aristocrat or barbarian king can influence actions some 128 inches from his base -- that's a little over 10 feet?! I cannot recall the last wargame that I played where the length of the table was 10 feet. In Mr. Avery's rules, ground scales are provided for a variety of scales. On page 12, he allows that 1 cm represents 10 yards in 15 or 20 mm scale.

The game scale for this figure scale is presented as 1 inch equals 1 cm. If I read this correctly, in a wargame set up that has Marius on the field, this Roman General would have a scaled command distance of 1,280 yards. This is just a shade under three-quarters of a mile. Perhaps this long reach is representative of messengers and or tribunes riding back and forth between the command base of Marius and engaged or moving units, but unless Marius has a very good cell phone, his capability or "effect" seems a little too all-encompassing. For lack of a better argument or example, if I were to stand at one end of a football field and try to exert some kind of influence on a conversation or water balloon fight taking place between a group of eight or nine friends at the other end of the field, well ... (I appreciate that the water balloon suggestion might be far fetched, but I don't think a circle of friends hacking at each other while armed with scutum and short swords would be very well received.)

The concept of leaders or commanders having to expend command "points" was one of the aspects which attracted me to investigate Vis Bellica. I think Mr. Avery is onto something good here, in that as the line begins to come apart or as certain commanders are not so capable, it is hard to address the status of each and every unit in trouble. However, once again, I had a little trouble understanding the process involved in the procedure. For a specific example, I should like to cite a paragraph from page 45, under the subsection of 8.2 Morale Check Results:

- "Unless rolling to rally, a base with shaken morale (bold type used in rules)that passes a morale test remains shaken. If it fails a morale test, it routs. If rolling to rally, a base with shaken morale becomes good morale. If it fails, it remains at shaken morale."

As I reread this section and look at the four bullet points on the opposite page to make sure when a morale check is required, I have to admit again, to my less than perfect wargaming mind. On the other hand, I should like to think that I'm a little more astute. Perhaps it is the way the information is presented? And again, I wonder about the condition of "disorder." Is it so "simple" a status that commanders can wave a magic wand and make it disappear without having to roll for it? Could Marius exert an influence on a disordered and or shaken unit from over 10 wargame table feet away?

Unrelated to any concerns expressed thus far, I began to wonder about troop endurance and fatigue as the combat in the center of the field continued. Pompey's legions were rather hardpressed. Those men in the ranks of the anti-Sulla forces were as well. I believe ARMATI has an optional rule about fatigue. I do not recall seeing anything about fatigue within the pages of Vis Bellica. To be sure, this is not to set each rule book against the other. It's simply something that crossed my mind as Pompey's leading two legions took the brunt of the fight in the center. I suppose that to an extent, their "exhaustion" was represented in the number of men lost, but it seems to me that perhaps some kind of modifier might be involved. Having typed that, I do realize it represents something of a contradiction to my previous observation about the "complexity" of the modifier table on the quick-reference sheet.

The more "significant" contradiction is this one where I "pass judgment" on a set of rules after just two solo-wargames / experiments in play testing. I have related that I think one should entertain at least three attempts at any new system. However, I think that in these two wargames - granted, one being more "Medieval" than Ancient - I have seen and or learned enough.

Overall, I think Mr. Avery's effort is a good one. As he states on the yahoo web site (and I will paraphrase): "no set of wargaming rules is perfect." It seems to me that I might amend that "rule" slightly to read, "no set of wargaming rules is perfect for me." In brief summary, I think what could have helped make these rules more palatable and perhaps more understandable, would have been a more concentrated design approach. That is to suggest, there is a dearth of graphics and concrete examples in the pages. To be certain, the rules are laid out in plain English so there can be little room for misreading. However, as evidenced by the discussion group for Vis Bellica, there appears to a certain amount of misreading. At the very least, there has been a substantial number of queries put forth and adjustments, amendments or explanations made. I feel that if there were specific examples contained in the text, accompanied by diagrams of various phases or sub-phases, a lot of this clarification would be unnecessary.

As this second "experiment" was played to its bloody conclusion and while the report was being typed, I began thinking about how some of my "objections" might be addressed. Mention has been made of the simple turn sequence used in the Fire and Fury rules. I have had some experience with these rules, have enjoyed the wargames "fought" with them and have seen and read how they have been adapted to other periods of conflict: most notably Napoleonics, but also the European Wars of the mid 19th century. If adaptation can be made for some periods, albeit in the musket and cannon era, could a similar adaptation be done for a non-gunpowder period? On the issues of game move sequence and the command rules, the concepts of Fire and Fury seem to "fit" very well into Ancients. On additional review, it appears that potential problems would present in these three areas: Scale; Missile Fire/Resolution and Melee Resolution.

I have not, as of yet, given any more thought to solutions for these perceived problems. The purpose of this narrative was to report on a wargame taking place during a period of Roman Civil War and to comment upon the rules used. Adapting concepts and mechanics of Fire and Fury to a much earlier period of warfare is an entirely different matter. It does give one quite a few things to think about, however. And it does almost lend itself to the research and preparation of another article for the pages of MWAN. Well then, it looks like I've got something to work on this spring and early summer. Now, where did I put that Fire and Fury rules book?

NOTES

1. In a chapter titled, "The Emergence of Rome," Charles Grant describes the make up of a Roman legion. Wargame Tactics, page 51. The Marian Roman army list in DBM Army Lists, Book 2, bears this out as well.

Back to MWAN # 130 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com