Although I have been playing 'wargames' of various sorts for over 25 years, I consider myself a relative newcomer to the hobby as a serious pursuit worthy of writing an article. Sure, I have a shelf full of board wargames and boxes full of miniatures-with legions of unpainted lead waiting for their first contact with the paintbrush-but for those of us who have gamed underground most of our lives, in our basements with small circles of friends (and yes, we are legion), the world of `professional' gaming is a host of conflicts the likes of which would seem to rival those we play out on the table top. Having been introduced to MWAN (No. 126) recently by Tom Dye of GFI, I was surprised to see that the hobby is still, to this day, hostage to debates that mark it's foundations as a `professional' venture in the 19th century. Sam Mustafa and Bill Haggart both argue in that issue (and continue to argue through the pages of MWAN #127 and #128) that it is time to break free from the historical constraints of these foundational debates. I would agree, but I would further argue that we first need to understand the history of the wargame's perceived utility as a "simulation." Without such an undertaking, we have little chance of breaking free of these historical constraints.

I refer of course to the debate between Mustafa and Haggart over the perceived need or desirability to categorize the hobby in a way that would standardize terms, scales, and levels of "simulation." Do games work, as Mustafa suggests in MWAN 124, because they "feel right" or do they work as Haggart suggests in MWAN 126 because they fulfill the operational criteria of "dynamic simulations"? As I entertain these questions, I feel it might be right to borrow the term ` operationalization" from the language of social science, the same language that gave us the professional notion of "simulation" with which Haggart approaches the issue. Game designers "operationalize" terms in the opening pages of their rules all the time: morale and unit efficacy being the most common examples of terms that are explained via a specific mechanic or logarithm outlined in the rules. Morale never just "feels right" as Mustafa would have it, but is specified as a term that will "operate" so that both players know how their units are doing. In that sense, what Haggart is arguing for is nothing more radical than "operationalizing" terms that will aid the hobby on a larger level.

Several other respondents have realized and accepted this in subsequent MWAN pieces this spring. Yet while I agree with Haggart that the term "simulation" is precisely the most problematic term for this hobby and therefore demands some sort of clarification, I also would tend to agree with Mustafa that attempts to clarify our meaning by operationalizing categories are likely to meet with resistance from gamers who just want to have fun. History, it would seem, favors both arguments. Here, however, I refer to a divide that is far older than the "ancient history" that Haggart invokes in discussing the debates at SPI or the work of James Dunnigan. Indeed, the history to which I refer is older than the birth of the gaming and simulations industries following the Second World War, and older even than the birth of the hobby through such popular works as those of H.G. Wells Little Wars. The origins of this conflict are to be found in the initial designs of the very first wargames (Kriegsspiel, properly called) of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

My hope is that in raising this earlier conflict among those truly professional wargamers, a middle ground can be found in which Haggart's desires for organizing the hobby become more possible without sacrificing Mustafa's organization of the hobby around our desires as gamers.

THE CATEGORIES IN OUR HISTORY

This is not the place to run through the full extent of what came to be known as the "Kriegsspielfrage" (The Wargame Question) in Germany following unification in 1871 (though if anyone would like that background, I'm happy to send that chapter from my dissertation ... complete with all the references!). As much as wargamers love to rehash history, there is little need in this instance beyond establishing one important categorical distinction about wargames, and then the subsequent historical distinction made by those who developed them for professional purposes in the 19th century.

The important categorical distinction relates to what exactly the purpose of the wargame was supposed (or presumed, but not necessarily intended to be). With this in mind, I would offer a quote from Karl von Muffling, Chief of the Great General Staff in 1824, upon witnessing a game designed by Georg Reisswitz in 1812:

- Why! Is your game played on real maps instead of a chessboard? Let's see, can you represent anything like the assembly formation of a division with your pawns? ....this is not a game; it is a veritable war school! It is my duty to recommend it to the whole army.

Von Muffling understood the purpose of Reisswitz's early game to be educational, and contrary to Ned Zuparko's view in MWAN #127; this is a very important initial consideration. The supposed "purpose" of a wargame has a direct correlation with the question of what it purports to represent, and here three categories come to mind.

In the first, the "historical representation," players will find themselves constrained not only by the historical environment, but also by historical events in which available reinforcements, weather, and other chance events will all be specified so that players are constrained to fight the very battle they are re-presenting. The purpose of this sort of simulation is the transmission of an historical understanding of the situation faced by historical commanders, and is primarily instructive.

In the second category, "historical simulation," players know they are constrained by the historical environment, including historical technologies and personalities, but not necessarily by the historical events of the particular battle. Stuart's cavalry may actually be at Gettysburg from day one in this sort of game, or the British may actually accept that it will take new methods of fighting to defeat the American revolutionaries. The purpose of this sort of simulation is to test the historical understanding of the players, and is primarily an exercise of that understanding.

Finally, in an historical game, the experience and the environment may look historical (for example, figures and terrain are reproduced historically), but the environment is governed by a general gaming mechanism which treats all the armies of several time periods as effectively equal. The educational purpose of this sort of simulation is simply to provide a visual appreciation of the heraldry and regalia of a time period by means of our beautifully painted "toys," and is more aesthetic than principled in nature. Another way to say that is that it's just plain fun. Yet each simulation represents something different in order to educate those who play.

Wargamer's today, whether hobby enthusiasts such as Haggart and Mustafa or those employed by DoD, spend a considerable amount of time arguing over the extent to which their creations can be considered simulations of the battles-real or hypothetical-they are designed to represent, and these categories may be useful to them in resolving those debates.

However, it is important to note that in their original professional development in Prussia/Germany during the nineteenth century, these games had one purpose only, and that was not to simulate battles, but to simulate the staff-work that was associated with planning the `modern' battles of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. It was, after all, precisely this sort of staff-work that the Prussian reformers of 1808 concluded was lacking among their military minds after 18061807, and it was to address this problem that the wargame was developed. Even in its earliest generic design, the wargame was, to quote Reisswitz "for the purpose of instruction and exercise," the first of my two categories.

Specifically, Reisswitz hoped that

- the composition of written dispositions, short orders and reports during the game,... [would] be a useful preparation for young officers in the realities of military service, and here the game relies to some extent on reality, about which much more can be said, than those simple supposed positions and maneuvers which exist only in the Ideal.

From the very beginning, then, the wargame's Prussian designers appreciated the difficulty of representing actual battles in any but an "Ideal" way, and indeed dismissed the notion that games could any thing more than an "idealized" re-creation of battlefields themselves. Their purpose was to train those who would run the battles from the staff tents in the rear. That said, the appearance of "game clubs" at most of the Regimental garrisons in Prussia throughout the 1830s and 1840s suggests the extent to which many officers also found them to be an enjoyable form of recreation well-suited to passing the time on long winter's nights. Even to one such as Moltke, who took the games very seriously indeed, they also just "felt right."

In raising these categories, I would like to advocate the same esprit de corps for the hobby as well. So long as battlefield enthusiasts (who number far more than Haggart) continue to insist that what wargames re-present is the battlefield itself, rather than an experience of the battlefield mediated through staff-work, we will be stuck in debates on whether wargames are, or are not, simulations of those battlefields. From a truly historical perspective, however, what a wargame simulates is modern military staff work, the techniques that proved to be necessary in order to command a mass army into battle, not to command in battle itself. Indeed, historical gaming outside of the modern period is possible only by historical analogy and the anachronistic imposition of such staff-work. To be completely literal about this question, wargaming is thus not a simulation of war, but a simulacrum, or a simulation of what is already a re-presentation of war. Any attempt to "operationalize" the hobby into a more "mature" endeavor must first admit this.

THE HISTORY BEHIND OUR CATEGORIES

Having established some categories, the second but no less important historical distinction to be made is one that arises naturally from debates about how best to accomplish this mission of instruction regarding the "realities of military service," and it is here that Haggart's and Mustafa's quarrel becomes so familiar. In point of fact, the same argument was waged in German in the Military History Department (KriegsgeschichtlicheAbteilung, or KA) of the War Department during the last thirty years of the nineteenth century. If, as Maj. Jakob Meckel, a leading advocate of the games argued, wargames were to serve officially as the means of education of officers," then the question that naturally followed was what the foundation of that education should be: experience, or theory. The KA quickly split between the "Rigid Wargamers," led by the Saxon Captain von Naumann, and the "Free Wargamers" led by a Major Meckel (then of the Hanoverian War Academy, but later head of the KA).

Von Naumann argued in his Regimental Wargame: Attempt at a new Method for Wargaming that "the leader of the regimental wargame...must rely on the casualty tables and the dice, firstly, to give his decisions the necessary authority, and secondly, above all to be able to offer the guarantee of a representation true to nature." What von Naumann wanted was a game that was fully "operationalized" from beginning to end, with no room for hedging or argumentation. The presence of the first recorded fire and casualty tables mathematically generated from firing range tests compared to historical results on the battlefield is proof of his desire to create an historical simulation based on a model representative of the combat of his day. On the other hand, Meckel recommended that players be freed from the complexity of learning such elaborate rules, and instead designated a single, senior officer as the leader of his games. It would be the leader's task to develop or learn the rules, and then his right to interpret them freely so long as these interpretations were grounded in "numerous, and when possible characteristic and varied examples..." rooted in lived experience.

Meckel, too, wanted to create an historical simulation, but the basis would be lived experience, not theoretical models. The historical conflict here is between lived experience as an instructional vehicle that can be transmitted to others, and codified principles that have been "operationalized" so that all can grasp common experience from them. Most Western military establishments embraced von Naumann's perspective, and "operationalized" their own principles of war in the early twentieth century, only to doubt (though not abandon) them later as modern warfare evolved throughout that century and into our own.

PUTTING HISTORICAL CATEGORIES INTO PRACTICE

These longstanding and deeply rooted disputes obviously linger in the arguments of Mustafa and Haggart. Though for our purposes the subject of the wargame has now moved from the politically and pedagogically important question of officer education to that of marketing a form of entertainment (or, for the truly ambitious, highly sophisticated computer generated combat sims for DoD), the fundamental tension remains. Mustafa suggests that simulations work because they "feel right" based on our experience (either lived, or mediated through historical research) whereas Haggart suggests they work because they fulfill the operational criteria of "dynamic simulations" that are specified in advance and thus test our experience.

For those who butter their bread with Defense Department dollars, the answer will have to lie with Haggart. Ever since the early strategic bombing surveys during the Second World War propelled think tanks like Rand to the top of the analytical A-list, complicated mathematical simulations that "operationalize" every aspect of warfare into algorithms have been necessary to win government contracts. It might seem obvious, then, that for those of us engaged in a hobby, Mustafa's criteria of enjoyment and feel would carry the field, unless of course what we're trying to simulate is the experience of contemporary training, rather than battle. That said, very few of us spend our dollars on lead, rules, and dice in order to increase our chances for promotion. We do it for enjoyment. Yet, what exactly is it that we enjoy?

If we consider the three categories I have proposed what we enjoy is one of three things. When we play an historical representation we enjoy the opportunity to learn how the past unfolded historically. We might lament the constraints we feel, but we come away feeling right about what we've learned. In an historical simulation, we enjoy the feeling that we must have learned something about the past if we can do well under similar, but not identical situations. When a game or scenario designer throws in a few historical change-ups, and we can still come away with a "win," that certainly "feels right" Finally, in an historical game, we simply enjoy the feel of the finely painted "toys" in our hands, and are far less concerned with a past, unless it is our own past as children, a past so many MWAN readers fondly recall in their letters. Clearly, there is enjoyment in all three, but I would argue that it is the historical simulation, as I have defined it, that truly captivates those in the hobby for the long run. If all we did was watch Waterloo play out over and over again, this would be a pretty dull activity. But we also clearly expect something more than your average fantasy role-playing game between "Orkz and Dwarvez" as Tom Dye put it in MWAN #127.

Haggart tried to address the question of enjoyment through comparisons to the RC airplane hobby, but I would actually draw a parallel to that fantasy gaming hobby which many feel is the antithesis of "historical miniatures gaming." The fantasy gaming hobby is divided between role-playing games (RPGs) and live action role-plays (LARPs). In the former, cardboard counters and/or lead miniatures are used to play out fantasy scenarios on a table top, while in the latter, players dress in costume, brandish weapons, and wander through mazes to achieve the same fantasy fulfillment in a more tangible fashion. While there are legions of military reenactor groups around the country, and indeed the world, this is quite clearly not what wargaming is about. As Haggart correctly points out, there is little desire among most wargamers to actually ride their lone charger or individual M1 A1 into battle. As veterans, many wargamers have already had something like that experience, and know it to be something best left to memory for the very real consequences it involves. If we as wargamers are involved in a live-action role-play, it is at best a simulation of the staffs in command of mass armies, and the staff-work that makes those real combat experiences possible.

Who among us has not watched classic war films such as "A Bridge too Far" or "Midway" and not longed for the experience of playing it out on a map as the actors do at Model's or Nimitz's HQ? Who among us pushing Napoleonic or Civil War lead has not imagined that the conversations we're having on "our side" are simulations of those that must have occurred in Napoleon's or Lee's tent? Wargamers do not long for battle, they long for command, for the full picture that only a representation of the battlefield can provide. From this perspective, much of this debate (in the hobby, and historically) seems quite literally misplaced with regard to what we believe our tabletops represent, and this is a substantial reason that game design has suffered in attempts to achieve the full level of "simulation" so many in the hobby desire. I will draw a bold categorical conclusion that wargames are useful as "simulations" when they represent the command and control aspect of warfare captured in staff-work, and they are mere childhood fantasy games when they attempt to represent the experience of the battlefields themselves. That may sound harsh, but I hope to have shown why I feel that distinction is necessary.

SIMULATING COMMAND AND CONTROL

If there is to be an innovative future in game design, it might just be one that combines the insights of Haggart and Mustafa to simulate the staff-work experience rather more than the battlefield experience. To this end, "operationaization" of certain aspects of that experience is welcome. In particular, "operationalization" in the realm of "scale" and "historical game dynamics" as suggested by Haggart seems to hold the most promise. As the hobby has expanded it has surpassed the constraints of scale and game dynamics imposed by the historical and cultural circumstances that produced the initial "regimental wargames" of the 19th century. Considerable efforts (and successes) have been made to produce games that represent anything from small skirmishes to grand campaigns, and yet, there is little clear appreciation for how the original regimental experience has formed our most basic gaming assumptions. The same can be said for our forays into earlier or more contemporary periods.

Despite the precedent set by foundational works such as Hans Delbruck's multivolume The Art of War in World History, it is simply not possible to apply "laws of tactics" developed in the late nineteenth century to every conflict that might be subject to representation. Sumerians, Greeks, and Carthaginians did not fight using the benefits of those so-called laws, and attempts to represent their battles historically should be divorced from them. So too, should attempts to represent cavalry charges led by Special Forces troops in Afghanistan. If the rules of war are changing, so too must change the rules of wargames attempting to simulate those changes.

That said, "operationalization" almost certainly has to occur along Mustafa's "chaos vs. control continuum" if it is to successfully simulate the experience of command historically. To make this point historically, consider the contrast between planning and execution in early modern warfare, perhaps in the period of Friedrich II, and the modern warfare of the recently completed Operation Iraqi Freedom. The difference between representing the planning experience of a Friedrich or Seydlitz and that of a Rumsfeld or Franks should be vast, marking nearly opposite ends of Mustafa's continuum. In the former `simulation,' players would draw up plans, "cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war" with little opportunity for intervention beyond the rolling of dice, whereas in the latter `simulation,' players would (and should) have infinite opportunities to `pause' (regardless of how one defines that), and make adjustments to the existing battle plans. Precisely because it is not the battlefield environment which we represent, but the commander's planning for that environment, game design should be dictated by the historical responsiveness available to the command level at which the game will be played. Here again, it is not mere "personal preference," but operational scale that comes to be a primary consideration or, if you will permit another social science term, the "independent variable" determining the location of the game on the chaos-control continuum.

At the smallest scales, players' control over individual troops or small units should be high but objectives and the freedom to plan, or change plans, should be limited. "Take that hill! I don't care how, but take it!" is the order of the day. The simulation challenge here is to fulfill that order no matter what surprises pop up. The environment may be chaotic, but responses are fluid because the number of men under command and control is small and staff-work is at a minimum. At the largest scales, designers should reverse these conditions. Once planned and unleashed, the opportunity to check forces and respond to countermoves in an operational or strategic engagement should be severely limited by command and control rules regulating the flow of information in all but the most modern scenarios. Pickett had no choice, and did his duty; he (almost) took that hill. At the operational level, however, the game to simulate is the choice that Lee and Longstreet debated, leaving it to the dice to decide whether Pickett's men will do their duty.

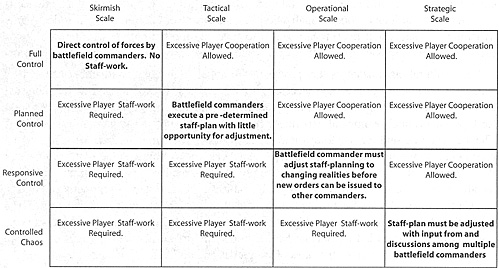

In Table 1, I attempt to depict this continuum as a matrix of game scale compared to player command and control. The ideal continuum runs diagonally across the matrix (in bold), while to either side of this line I have indicated what I judge to be the two most common problems with games that drift away from that ideal continuum.

In Table 1, I attempt to depict this continuum as a matrix of game scale compared to player command and control. The ideal continuum runs diagonally across the matrix (in bold), while to either side of this line I have indicated what I judge to be the two most common problems with games that drift away from that ideal continuum.

Table 1 assumes a nineteenth or early twentieth century army that conforms to the staff-work considerations that were the foundation of today's wargames: information is communicated on paper, and that paper must be shuttled between battlefield commanders. At the smaller scales, too many command and control rules require much more staff-work than would be expected of a 2nd Lt. or even a Captain in the field. At larger levels, a lack of command and control strictures allows players to operate with a "god's eye view" and cooperate on a level unimaginable to their historic counterparts. modern means of communications, however, shift the location on the control vs. chaos continuum toward the upper left, and thus toward greater levels of control. After all, a battalion net doesn't really need a "command radius" to operate.

This may seem counter-intuitive to many, and so is worth further elaboration. While it is true that on the battlefield small unit commanders have less control because they have less information about the big picture, they also have less reason to care about it. They're saving their own butts, and hope the fellows to the left and the right are doing the same. However, in a game that simulates the actual staff-work involved in communicating the big picture to smaller units, the challenge becomes much more difficult at higher levels, not easier.

Knowledge is power only to the extent that it can be effectively communicated to all units, and this refers specifically to the ability to write clear orders, something Reisswitz and other early game designers stressed as the essential educational benefit of their games. If knowledge of the battlefield is not effectively communicated to subordinate units, the elaborate plans of many gamers would come crashing down faster than the Prussians at Jena, and this is precisely what wargames as simulations of war were meant to educate against. Yet, the "operationalization" of command and control in many games actually encourages these delusions of grandeur rather than educate against it.

The situation in many game designs is the exact opposite of what wargaming was invented to do because what game designers (and many players) want to simulate is the thrill of command in battle (as Haggart points out, just read those box tops!) rather than the thrill of command of a battle. Rather than charge once more into that breach and risk fighting the same battles over and over-off the table-top as well as on it-we need to do a better job with the second of these options. Perhaps the easiest way to do this would be to admit that what our hobby represents is what most of us really are (the guys in the rear, with the gear, and occasionally the beer). If we simulate that, we just might find a happy compromise that will allow for some truly innovative and rigorous game design, and a little more of what "feels right."

Back to MWAN # 129 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com