The Nine Year's War (1688-1697) is the Rodney Dangerfield of wars: it don't get no respect. There are few direct references to it, and when it is mentioned, it is often followed or preceded by a slash, as in "War of the Spanish Succession/League of Augsburg," or even "Thirty Year's War/League of Augsburg"(!). Indirect references are not hard to come by, but they are almost exclusively limited to discussions of developments in warfare, like the rise of the bayonet, that were happening at the end of the 17th century. Oddly enough, few of these references actually mention that these transitions were happening during the course of a great war, a war that was second only to its big brother, the War of the Spanish Succession, among Louis XIV's wars. The War of the League of Augsburg, with its colorful mix of units and unit types, multiple armies, direct and indirect links to practices common to later eras, historic personalities, and breadth of conflict, is a rewarding combination of the best that the Lace Wars and Pike and Shot eras have to offer.

The Nine Year's War (1688-1697) is the Rodney Dangerfield of wars: it don't get no respect. There are few direct references to it, and when it is mentioned, it is often followed or preceded by a slash, as in "War of the Spanish Succession/League of Augsburg," or even "Thirty Year's War/League of Augsburg"(!). Indirect references are not hard to come by, but they are almost exclusively limited to discussions of developments in warfare, like the rise of the bayonet, that were happening at the end of the 17th century. Oddly enough, few of these references actually mention that these transitions were happening during the course of a great war, a war that was second only to its big brother, the War of the Spanish Succession, among Louis XIV's wars. The War of the League of Augsburg, with its colorful mix of units and unit types, multiple armies, direct and indirect links to practices common to later eras, historic personalities, and breadth of conflict, is a rewarding combination of the best that the Lace Wars and Pike and Shot eras have to offer.

The Nine Year's War lies in the overlooked gap between two more well known eras, namely, the English Civil War (ECW) and the War of the Spanish Succession (WSS). Compounding this gap is the fact that it is a very difficult era to research, at least in English. This has led to it being appended to other eras, most usually the WSS, as a sort of minor version of the same. Regarding this linkage to other eras, I would suggest that the armies of the Nine Years War are more "backwards compatible" (like to the War of Devolution, 1667-68, and the Dutch War, 1672-78, maybe a bit before them) than they are forwards. The shift in warfare between 1670 and 1690 was evolutionary, making the armies pretty familiar to each other. On the other hand, the shift in warfare between 1690 and 1701 was revolutionary, marking a clear division between the eras (I will outline the salient differences between the armies of the LOA and WSS later in this article, dear reader, if you will but indulge me until then).

The Nine Year's War (or War of the League of Augsburg, hereafter referred to as LOA for short) was the last of the general European "pike and shot" wars. When imagining the pikes of this era, though, one cannot look back to the ECW or Thirty Year's War. The LOA pikes were not organized for shock and melee, but were employed to protect against cavalry. Having said this, it is also important to point out that this was also a time of great transition. The LOA armies were on the cusp of two eras, still having the spirit and resembling in many ways the armies of the 17th century, but also increasingly mixed with the emerging technologies and military practices of the early modern era. Additionally, although it was not a religious war in the same sense that earlier wars of the century had been, the LOA certainly had religious causes bound up in it, especially from the English point of view, making it, in part, the rearguard of the European religious wars.

WE CAN'T JUST ALL GET ALONG

WE CAN'T JUST ALL GET ALONG

The lead up to the war itself is complicated and happened at a very interesting time. In 1685, Louis XIV, figuring that a Sun King didn't have to "tolerate nottin'," rescinded the edict of Nantes, which had ensured tolerance for French Protestants (Huguenots) since 1598. This was seen as a provocative move, both inside and outside of France. Thousands of Huguenots left. In 1686, the nearby German states, the United Provinces, and also the Holy Roman Emperor (always happy to take a dig at the Bourbons) formed the "League of Augsburg" as a protective measure: soon after, Spain, Sweden, the German Duchies and Principalities in Northern Europe, Bavaria, and Savoy would join.

When Charles of Lorraine turned back the Ottoman threat at Buda in 1686 and Belgrade in 1688, it meant that Austrian Hapsburg power could be concentrated against France. Now it was Louis XIV's turn to be concerned. The French besieged Philipsburg and moved into the Palatinate as a pre-emptive measure. It worked. Things shortly escalated into a great war between France and the members of the League of Augsburg.

While this was going on, the Glorious Revolution in England led to the rise of Protestant, anti-French William III, sending Catholic, Pro-French, James II (now deposed), to France, bringing with him an army of 20,000 mainly Irish expatriates, the original "Wild Geese". On the other side of the expatriate coin, French Huguenots would serve in large numbers, both individually and as stand alone units, in nearly all the Armies of the Grand Alliance. The Williamite English Army, for instance, had 5 regiments of French Huguenots. The Elector of Brandenburg's Grand Musketeer Squadron, composed of French "gentlemen" richly uniformed in red (sort of anti-musketeers, in small, to those of the Maison du Roi), was perhaps the most unique, if not the most numerous, unit of French expatriates. France would declare war on Spain in 1689, causing the "Grand Alliance" to be formed in response, which included the members of the League of Augsburg along with a few more, like Brandenburg-Prussia, Brunswick-Hanover, and England.

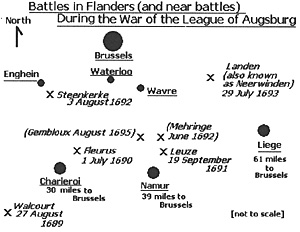

At this point, most if not all of Western Europe was arrayed against France. The war would go on for 9 Years and be active on three major fronts: Northern Italy, Flanders, and Rousillion/Catalonia. The Rhineland was the seat of campaigning as well, but there were no major battles there (more on that later). Unlike the War of the Spanish Succession, the French would win every major battle after the first (which was Walcourt, 1689). Like the War of the Spanish Succession, battlefield victories would not translate into decisive results. Both would be "wars of exhaustion" as John Lynn puts it.

THE VERY MODEL OF A MODERN MAJOR WAR

Part of what has obscured the era, apart from the absence of source material, is the general impression that the LOA was a morass of siege work and otherwise uninspired tactical level combat (play along with me here; pretend that you had an impression, at least). Closer examination reveals more of interest than these generalizations would seem to indicate. The main theater was Flanders, which would certainly mean, especially pre-1800, that there would be sieges and fortified lines to deal with, to be sure. It is interesting to note, though, that over a 4 year period (1690-93), there were actually as many open battles in the Flanders theater (4) during the LOA as there were during an 11 year period (1702-12) there during the WSS. Moreover, if you consider the LOA as a two-period event, early and late, the overall non-siege activity level of the early period (1689-94), Flanders included, compares favorably to similar stretches of warfare in other 17th and 18th century wars.

LUXEMBOURG-NOT LIKE THE LAST THREE LETTERS OF "BENELUX"

LUXEMBOURG-NOT LIKE THE LAST THREE LETTERS OF "BENELUX"

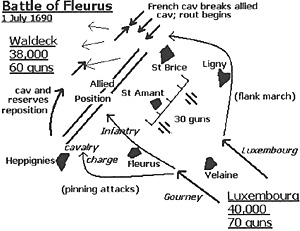

Sieges aside, the battlefields of the LOA were no sleepwalk. One of the overlooked great captains of history, Luxembourg, was a bold tactician who led the French Army in Flanders up to his death in 1695. He was a commander in the same tradition as Turenne and Conde before him, and would be known as the "upholsterer of Notre Dame" for the number of colors he would capture in the war. His masterpiece at Fleurus, with a pinning attack by half his army and an enveloping attack by the other half, is a fine example of the kind of envelopment battle that Napoleon would employ a little over a century later. The French crushed Waldeck's 38,000-man army there, seizing 100 colors, taking 8,000 prisoners, wounding 3,000, and killing 6,000. This battle also demonstrates that the armies of this period were capable of more than doggedly lining up in a fixed array and then going through the motions of a battle according to a formula. One interesting aside to this battle is that it led to the creation of a French regiment. The Swedish brigade in the middle of the allied line gave up some 500 prisoners that day. These men would later take service in the French Army and form the core of the Sparre Regiment, which would remain in service and become the Royal Suedois (Swedish) Regiment in 1742.

BATTLE OF LANDEN, 1693

The largest action of the war, the battle of Landen (alternately known as Neerwinden), consisted of a French frontal assault against William's camp behind a line of fortified towns and works, which hardly seems to be a recommendation for interest. Yet this would be the model for many battles that would come in later eras, like Malpaquet, Ramilles, and Blenheim in the WSS, and Fontenoy in the War of the Austrian Succession, to name a few. Most of the French commanders, after a bloody seesaw action that had seen the French take and be repulsed from key positions twice, recommended ending the battle.

Luxembourg, however, saw that victory could still be had and reshuffled his forces for a third assault, which carried the day. The last units in the works for the allies were the Coldstream Guards, who were next to the fortified village of Neerwinden, which had been garrisoned, in part, by the English Foot Guards. The village had been stormed, in the end, by the French and Swiss Guards.

BATTLE OF STEENKERKE, 1692

On the other side of the war, William III's attack at Steenkerke, with his left flank protected by the river Senne and his right flank refused, anticipated Frederick's oblique attack at Leuthen, even if the results of the two engagements were very different. Leading William's attack were the English Foot Guards and the Danish Guards, and it was the French Guards who counterattacked to check their advance. There was much hard, close action fighting that ensued as William's attack turned into a fighting withdrawal over the broken ground through which they approached. The French and British were shooting at each other from the opposite sides of hedges, literally, at times.

It may be speculative, but it's not hard to imagine that the rivalry between the British and French Guards, which would culminate so famously in the exchange at Fontenoy, were planted during these LOA engagements.

SAVOY TO CATALONIA

The campaigns were very dynamic in Italy (Catinat vs Savoy) and Rousillion/Catalonia (Noailles vs various Spanish Generals), with small field armies ranging from 12,000 to 20,000 engaging in the full range of operations, including open battles. In Italy, Catinat, another great captain, prevailed over Victor Amadeus, Duke of Savoy, in open battle at Staffarda (18 August 1690) and at Marsaglia (4 October 1693), both battles involving active generalship and hard fighting. Eventually, Victor Amadeus would change sides in 1696, but the Italian Campaign up until then anticipated the Revolutionary/Napoleonic campaigns in Northern Italy with a small French Army maneuvering against much larger forces. In Spain, forces were usually smaller, peaking at 20,000 or so, both sides employing the irregular miquelets of the region as light infantry. The largest battle on that front was also a French victory, the Battle of the River Ter in 1694.

Interestingly enough, the French infantry carried the fighting in Italy, and Catinat credits his infantry for winning his battles. In other theaters, the French infantry was considered uneven. Therefore, Louis instructed his generals to limit the infantry fighting as much as possible, since the French tended to get the worst of it, and to seek a decision with cavalry, which is indeed how most battles seem to have been won. Conversely, the allied infantry, British and Dutch especially, usually acquitted itself well, even in lost battles.

GAMERS GO WHERE GENERALS FEAR TO TREAD

Happily, the hypothetical is of almost as much interest to the gamer as is the factual. It provides the material for many a "what if' scenario (look for them at a convention near you soon!). Adding to the LOA's actual list of battles, there are also several "near miss" events that occurred in Flanders that can be explored. In June of 1692, William marched south from Brussels to lift the siege of Namur, and Luxembourg's 60,000 man army of observation moved to Longchamps, a few miles Northeast of Namur, to meet him. A rain swollen river at Mehaigne, however, prevented what would have been perhaps the largest open battle of the war from happening near there. In an inverse operation, in August 1695, Marshall Villeroi, who had replaced the deceased Luxembourg, marched an army of 73 battalions and 153 squadrons to lift the Allied siege of Namur. This time, it was William who marched with an army of observation (some 75 battalions and at least 80 squadrons) to a position near Gembloux to block him. Villeroi scouted William's position and deemed it too strong to attempt: another battle missed.

In the Rhineland, maintaining the status quo and keeping the enemy from gaining a strategic advantage was more important than risking a major battle. Unfortunately, this led to a sort of kabuki dance of a campaign, where armies would repeatedly bluff and confront each other, but spill no blood (we can only guess whether or not they painted their faces and grimaced). Taken in isolation, this is the sort of thing that has given the LOA a bad name, I think. It may have made some sense strategically, but it doesn't provide much interest below that level.

The good news is that these moments still provide good grist for the scenario mill. The most promising of these face-offs occurred at the end of July 1693 when Baden (the allied commander) and De Lorge, each with some 45,000 men, faced each other on the east bank of the Neckar near Heilbron. The Dauphin (with De Lorge's Army) and Baden traded barbs via courier, and both sides had maneuvered there with battle in mind, but a violent storm sent the French camp into confusion, stampeding the horses, and causing the French to withdraw. The next most promising confrontation came on 12 July 1697 when Baden blocked Marshal Choisel's advance on Strasbourg, and both armies stood a league apart for some time. On 10 September 1696, Baden and Choisel's armies lined up on the high ground on either side of Neustadt, once again without engaging. In 1695, the French and the allied armies in the Rhineland were encamped within 10 miles of one another, at Bretton and Eppingen, respectively, southwest of Heilbron. When the larger allied army, a combined force consisting of the Landgrave of Bayreuth's Germans along with Baden's Imperials, decamped and moved to engage Choisel, he decamped and headed for Heidelberg.

I'M WITH STUPID

This era has a fascinating mix of units and forces, in the coalition armies in particular. The armies were fairly evenly matched, relatively small, and almost entirely professional. The subsidy system allowed smaller states to maintain sizeable forces, and they specialized in providing military service to client nations, the largest "consumer" nation being the United Netherlands. Consequently the units of the "minor" powers cannot be dismissed as having minor capabilities. Many were as proficient as those of the larger powers. As a matter of fact, they composed a significant portion of the armies. For instance, nearly the entire Brandenburg Prussian Army, to include Guard units, was in Dutch service at one time. Aside from these subsidy troops, armies would also have "national" contingents from coalition partners as well, leading to a varied and colorful force. The French Army may not have had subsidy troops and coalition partners like its adversaries, but it certainly had the full compliment of colorful foreign regiments, and even expatriates, that it is famous for.

A HORSE! A HORSE!

Cavalry made up about 1/3 of the actual field army as a rule, but could go higher. Regarding the actual number of formations, the ratio was about 3 cavalry squadrons to each infantry battalion. Large armies of the day ranged in the 50,000s. The battle of Landen was especially large, seeing 80,000 French against 50,000 (plus) Allies. Here are some examples of representative armies of the war: Luxembourg's Army in Flanders in 1691 was 49 battalions and 160 squadrons. William III, in that same year, commanded 63 battalions and 180 squadrons (56,000 men). Louis XIV commanded an Army in the 1692 campaign composed of 40 battalions and 90 squadrons while Luxembourg's assembled army for the same campaign consisted of 66 battalions and 205 squadrons (!).

GUARDS! GUARDS!

This was the heyday of the guards. The proportion of guard to line units in this period is unlike any other I can think of. The unique combination of the old (royal and aristocratic prerogative to raise troops) and the new (the modern standing army with standardized formations and units), led to this, I think. The sovereign, be he a king, a duke, a prince, or an elector, would, as a matter of prestige, raise the best, often biggest, regiment-or regiments-in the army, and he would employ the state's resources to ensure that these units were kept at full strength. Now, however, instead of a fighting bodyguard of horse or of foot, as in previous eras, they were raising battalions and cavalry regiments that would also hold positions of honor in the lines of battle, and also take precedence in combat. Combine this with the relatively small size of the armies of the era, and you have a time period where the guards were very much in the thick of things.

Here's a good example: at the battle of Fleurus, Luxembourg had 34 infantry battalions, 6 of them guard (4 French and 2 Swiss in the Brigade Segurian). If one just counts formations, 20 percent of the French infantry battalions, roughly, were guards. The French were not unique in this. The English Army had a large establishment of guards as well, which still included William's Dutch Guards at the time. Add to the gross number of formations the fact that guard units were usually larger than their line counterparts, and were much more likely to be at full strength, and the calculus of the guards' relative combat power gets even more significant.. It was much the same with the mounted arm, especially the French. The Maison du Roi represents a body of nearly 2,600 cavalrymen who were brigaded with the Gendarmie, who could easily increase the total to 4,000 elite horse who were committed en masse. This could represent as much as 25 percent of the total cavalry force for an army of 50,000. The guards, when they were present, weren't so much the last reserve of an army as much as they were the heart of it.

Both honor (old) and necessity (new) combined to involve the guards in the thickest fighting. When Luxembourg struck out on his bold raid against Waldorf's rearguard of 75 squadrons and 5 battalions at Leuze, he took with him only 28 squadrons, but they were mainly from the Maison du Roi. As I have already mentioned, the Williamite guards led the attack at Steenkerke, and British guards were posted in the most critical points in the line at Landen. It is clear that the guards were not spared combat, but the inverse. In another one of those early 17th century echoes that makes this era so fascinating (to me, anyway), the King's Musketeers, of Alexander Dumas fame, were among the 7 battalions that stormed the La Cochette redoubt during the siege of Namur in 1692. The Musketeers of the Maison du Roi were not dragoons, but they were trained to operate both on foot and mounted, and it was during an earlier siege, Maastricht in 1673, that the real d' Artagnan, by then 58 and commanding the Musketeers, was killed.

SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW

The LOA was a 17th century war, chronologically, with one foot sliding into the 18th century. As such, its units were "modern" but still evolving.

So,You KEEP FISH OR SOMETHING IN THAT HELMET?

The Imperial, Bavarian, and Spanish Cuirassiers were still in their lobster pot helms and back and breast armor, the Spaniards being especially interesting given their blackened armor and yellow coats. All non dragoon horse was basically heavy. In the age-old swing between cuirass and no cuirass, this was more of a "no cuirass" era, but there were exceptions and interesting variations, like the Wurtemburg Hochstadt horse with leather cuirasses worn outside the coat, and the Prussian horse-known as cuirassiers-with leather cuirasses worn under the coat. Of course, the French Cuirassiers du Roi were in existence before the war, and wore their cuirasses on the outside, as always.

PLUGS AND PIKES

Plug bayonets, pikes, matchlocks, and flintlocks were all in use throughout the period in various degrees. The socket bayonet had been introduced, but the main bayonet, when it was present, was the plug bayonet. Some Armies, like the Danes, the Bavarians, the Austrians, and the Saxons, had abandoned the pike by the start of the war, while most others still had standard pike and shot infantry formations with a few units of "fusiliers" serving separately. The ratio of pike to shot was always changing, but something like 1:5 is a generally accepted rule of thumb for the LOA. In place of the pike, though, the Austrian and Saxon infantry still carried a swine-feather or "boar spear" to defend against cavalry, which implies that the bayonet may not have been fielded widely or at all among them, and in the case of the Imperials, they certainly did not take the corresponding step to upgrade to flintlocks (one step forward, one step back).

LIGHT IT. THEN THROW IT!

Experiments and revolutions in military theory and practice that began in the 1670s had matured into common practice during the 1690s, but still had a unique "early" flavor to them. Grenadier companies were by this time standard, but grenadiers still carried their grenades and retained their specialized roll in sieges and fighting in works. For instance, 20 companies of grenadiers were massed opposite the breach at Ath in 1697 preparing to storm it when the governor appeared there and capitulated. Dragoons increasingly fought in the saddle alongside the horse, but they were also commonly dismounted and massed for sieges, assault operations, and to hold outlying positions. It was a force of 2,500 dismounted French dragoons who stormed the fortified village of Neerlanden on the Williamite left flank at Landen.

SAKERS AND FALCONS AND GUNS, OH MY!

Cannon were still commonly referred in terms familiar to the late renaissance and Thirty Year's War : "sakers," "falcons," "culverins," "demi-cannons," etc. Standardization was being introduced, with the familiar shot-weight measure being adopted during this period (4 pounder, etc). A professional, uniformed, artillery corps was in its infancy in all armies of note. Civilian gunners, therefore, were a thing of the past, but transport was still handled by civilian drivers.

Guns, nevertheless, were idiosyncratic, and many of them were still in service from earlier decades, so that assumptions regarding the similarity of two pieces, which might both be categorized as 4 pounders (for instance), cannot be drawn. One might be "light" and the other "field" in effect. An interesting note on the guns of the period is that each had to be a functional fortification piece as well, necessitating that they have extended barrels that could clear the works. This gives the "late renaissance" look to the artillery of this era, with even the light pieces having long tubes. This elongated barrel also would add to the gun's weight, however. The term "light" does not necessarily equate to "mobile" when used in reference to the artillery of this era.

THE REDCOATS ARE COMING-ALMOST CERTAINLY!

National uniforms were either being adopted or already had been, many of them in recognizable form: The French and Austrians were in the grays that would morph into the whites of the 18th Century; the Brandenburg Prussians had adopted their dark blue, the Bavarians their cornflower blue, and the British their red (very recently). Some armies, however, like the Saxons, would change basic colors during the LOA or between the LOA and the WSS (Saxony switched from gray to red beginning in 1695, for instance), so you have to be on your toes if you use WSS references for uniforms. The round hat was in use, another 17th century flavored aspect, but was morphing into the tricorne. Speaking of hats, the Hanoverian cavalry wore white felt hats during the LOA, switching to the black tricorne after 1700.

WHO ARE THOSE GUYS?

The warrior-king (and prince) was still very much the ethos of the day: the Duke of Bavaria, the Elector of Brandenburg, the Duke of Savoy, and the Duke of Wurttemburg commanded armies in the field. Louis XIV still took the field at the head of an army in the early part of the War, and William III personally led the armies of the Grand Alliance in Flanders. Famous 17th century leaders were still kicking around for the early stages of the war, like Charles of Lorraine. This period also had living links to the captain-generals of the late Thirty Year's War and the wars of the mid century. Villars would recall the thrill of witnessing the bootless (due to gout) Great Conde leading cavalry charges at the Battle of Seneffe in 1674. Up and coming were familiar figures among the Grand Alliance, like General Churchill (involved only briefly due to political issues), and Prince Eugene of Savoy. In the French camp, the generals of the WSS, notably Villeroi, Tallard, and Villars, held major commands during the LOA. Leading those 20 companies of Grenadiers at the siege of Ath was another figure that would be familiar to followers of the WSS: Marsin. Vauban himself led the Sun King's sieges, and he faced off against the other great military engineer of the age of siege, Coehoorn, at the siege of Namur

CONTEMPTIBLE LITTLE ARMY, BUT A BEAUTIFUL BABY

This time saw the birth of the British Army as we know it. Its oldest regiments' lineage are rooted in the Glorious Revolution, and the first battle honors come from the LOA (Steenkerke). The Scot's Grays are held to have acquired their distinctive mounts from a Dutch horse regiment that was redeploying to the continent after the campaign in England. With the rise of William of Orange to the Throne as William III, the LOA also marked the start of the major engagement of the British Army on the continent, an involvement that would run for the next 125 years (through the end of the Napoleonic wars).

During William's campaign in England and Ireland, his British infantry had an indifferent reputation (references cite that were it not for William's Dutch and other foreign troops, he would not have carried the fighting), but the signature stubborn fighting qualities the British Army (the foot in particular) were established in the continental fighting of the LOA. British units invariably stand out for mention even in the battles lost, like the 6 regiments of English horse that went into action while the allied army was routing around them at Landen, and the countercharge of the English Horse Grenadiers at Leuze, amidst another allied rout, that brought a horse grenadier into personal combat with Marshall Luxembourg himself.

THE ARMY OF THE FOUR FREDERICKS

Like the British Army, Frederick the Great's army also had its genesis in the LOA. The recently deceased (1688) Great Elector (Frederick William) of Brandenburg had reformed and greatly increased Brandenburg's army into a respected force during his reign and a central pillar of the Brandenburg state. Although the Great Elector's successor, Frederick, was not himself a military reformer, the military force that he inherited on the eve of the war was considerable, and made a significant contribution to the cause of the Grand Alliance.

As a result, Brandenburg would have the leverage to be recognized as a kingdom in 1701 when its army was needed once again against the French, the Elector Frederick then becoming Frederick I, King of Prussia. In 1713, another military-minded Prussian ruler would take over, Frederick William I, and he would further advance the Prussian Army into the military machine that his son, Frederick II (the Great), would make history with.

HAIL, HAIL, BAVARIA ...SUNG TO THE TUNE OF "HAIL, HAIL FREEDONIA")

In an epic case of bad timing, Bavaria sided with the Grand Alliance against France during the LOA, and so suffered the many lumps dished out to allied armies then, and allied with France during the WSS, what happened at Blenheim hardly needs recounting. All that aside, the forces of the "Blue King" campaigned hard in the LOA and were actively involved in coalition armies in Flanders, as well as in other areas. The Elector of Bavaria was also the acting governor general of the Spanish Netherlands, and as such, commander in chief of the Spanish Army of the Netherlands. Therefore, he personally campaigned with William in the main theater of war, Flanders. He commanded the right wing of the allied cavalry at Landen and it was the charge of the Bavarian cuirassiers there that routed the French cavalry on their first breakthrough, and they again charged to restore the allied line after the second French breakthrough. Although Bavaria would be partnered with France in the WSS, the LOA represents the end of the golden era of Bavarian status. The next century would reduce Bavaria to a minor power in comparison.

THE GOLDEN CROISSANT

The French LOA army represents the end of the era of the French Army as the dominant fighting force on the continent, a prime that was ushered in by Conde at Rocroi 50 years earlier and cemented in the 1670's when men like Col Martinent (of the Regt Du Roi) instituted reforms and standing procedures that would create the first "modern" standing army. In general, the French LOA-era army was more akin to the force wielded by the Great Conde and Turenne in the War of Devolution (1667-68) and the Dutch War (167278) than the one that was crushed at Blenheim in 1704 by Marlborough. Additionally, French battlefield leadership at this time was on the cutting edge, at least competent and often excellent (Luxembourg never lost a battle). According to some sources, the French Army was a victim of its success during the LOA, leading it to fail to reform before the next major war.

POTATO TOMATO

Comparing the LOA to the WSS is, in large part, like trying to compare tubers and fruits; more a matter of contrasts than similarities. Complicating the situation is the common misunderstanding regarding the nature of the tomato. Folks don't even realize that it's not a vegetable to begin with (it's a metaphor ... follow along, please). Contrasting the LOA to this more familiar period, though, is a good way to understand it. Towards this end, here are some of the salient contrasts between the two, and should come in handy if you are contemplating converting WSS rules to LOA events:

DUDE, WHERE DID YOU LEAVE YOUR FISHING POLE?

With a few notable exceptions, the LOA infantry units of the major combatants had a significant pike component; there was no significant pike component remaining anywhere during in the WSS that I know of. This, by itself, makes for a drastic difference in character.

WHOA, I JUST SHOT MY BAYONET OFF TOO COOL!

Bayonets were still being introduced during the LOA. Although the English Army introduced the socket bayonet sometime during the war, it was not a widespread item. It can be safely asserted that the LOA was a plug bayonet war (and a "no bayonet" war in many cases, like the matchlock/pike units); in the WSS, the bayonet was a standard item of equipment, and was of the socket variety, even though the French didn't start converting from plug bayonets to socket until around 1703. This also makes a huge difference between the eras in the role of the musketeer and the basic employment of the unit.

LIKE, IT'S A FLINT. AND A MATCH. ONLY IT ISN'T?

Although it was being replaced, again in very uneven fashion, the matchlock was still present in large numbers throughout the LOA. The subject of the distribution of the various musket types used during the LOA is bigger than this article, but it is safe to say that the matchlock was the standard firearm during the LOA. So you still had, in many cases, the matchlock and pike combination of earlier eras; this was not the case for the WSS. Although there were exceptions, the largest being the Imperials who largely maintained the matchlock throughout, the WSS was basically a flintlock war, another basic point of difference between the WSS and LOA units.

UMMM, LEMME SEE. I FIRE, THEN WALK TO THE BACK OF THE FILE...

Firing drills were still in evolution during the LOA, and there was no distinction, practically speaking, between the opponents, both sides employing fire by ranks, files, or divisions, with musketeers arrayed in five ranks; the actual moment that the Anglo/Dutch adopted the platoon firing system, and how universally it was instituted before 1700, are matters of debate, but it can be safely said that during the WSS, the distinction between the French and the Anglo/Dutch firing systems, leading to basic differences in depth of formation, etc, is a well established fact..

TOP OF THE WORLD, MA!

Most notably, and perhaps most misrepresented when applying rules from later eras to this one, the French LOA cavalry was not the trotting and retreating French "firearm cavalry" model of the WSS. The French cavalry consistently defeated the allied cavalry, despite the individual qualities of some of the regiments, like the British and a few others, leaving the doughty allied foot to stubbornly fight its way off many lost battlefields on its own. In the words of David Chandler in The Art of War in the Age of Marlborough, "Throughout the War of the League of Augsburg, indeed, there seems to have been no stopping the French cavalry" (53). For instance, the main reason William III conducted the difficult march and attack through the broken ground separating the allies and the French at Steenkerke was because it allowed him to avoid the French cavalry. At Leuze, Luxembourg's 28 squadrons routed 75 allied squadrons and 5 battalions of foot.

(As an aside, Pat Condray, in his introduction to the Third Edition of his Wargamer's Guide to the Age of Marlborough asserts that the standard belief in the universal absence of effective French cavalry shock action during the WSS is an over-generalization and needs to be reassessed, something I would tend to agree with, but which is beyond the scope of this study).

CONCLUSION AND GAMING THE LOA

CONCLUSION AND GAMING THE LOA

And that, gentle reader, concludes my introduction to the War of the League of Augsburg. If, like me, you are an inveterate "gapper" (gap gamer), then the LOA presents an especially rewarding project, and is, perhaps, the mother of all gaps. My Volley and Bayonet (VnB) variant for wargaming in the League of Augsburg (also within these pages) contains more direct advice on gaming the period (along with the tidbits I've mentioned throughout in this piece), including notes on army composition as well. So even if you aren't familiar with VnB, you may still find something of use there. If you would like one for yourself, the most updated version is available for download, along with player reference sheets, in the Volley and Bayonet newsgroup. It is also online, readable in your browser (but not updated), on the Volley and Bayonet website (see the bibliography for the links to both sources).

There are various vendors who carry either a LOA line or figures suitable for the LOA. I have found everything that I have needed by using Irregular supplemented by Baccus. While writing this article, I ran across Venexia miniatures, who produces a superb line of 15mm LOA figures, complete with regiment packs and painting guides (very handy, to say the least!). I will add a disclaimer that I haven't had much time to do much figure research, so don't take my recommendations here as definitive.

Ultimately, I wound up mixing figures from different eras to get what I consider to be a period-correct looking miniature army. Most LOA lines are short some items, leaving you to improvise a bit: late renaissance and 18th century guns and a mixture of gunner figures from the WSS, ECW and LOA; 18th century French Dragoons with stocking caps (the uniform didn't change much in the WSS); a smattering of 18th Century grenadiers in short and tall mitres, and even early bearskins (for British Fusiliers); early lobster pot cuirassiers; a mix of ECW and WSS command figures, you get the idea.

The biggest overall difference in look between the LOA and the WSS, pikes aside, is the predominance of the round hat during the LOA (although, as usual, sources disagree on the permutations of headgear and when round hats began to look like tricornes). As far as I'm concerned, there's no point in having my LOA army look like a WSS army, so round hats it is! My final piece of advice to you, if you are interested in gaming the League of Augsburg, is that as long as you are gapping, you might as well gap all the way: do your armies in 6mm! Good gaming, and look for me (and my little armies) at a convention near you.

ED'S BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR GAMING IN THE WAR OF THE LEAGUE OF AUGSBURG:

You will notice many references that do not appear to be "on topic." This is symptomatic of the era, but there is a great deal of information available "at the edges" of references that deal with other eras. I make no claim to being an expert on the era. I've simply synthesized the material that others have provided (hopefully, saving others a few steps). For the real experts, check out the sources. Probably the best single reference on the era is Grant's From Pike to Shot. It has the only detailed descriptions of LOA battles I've found (Steenkerke and Landen) and covers the larger era, pre and post LOA, very well (although it contradicts other sources on a few points, but that is pretty normal for this era).

Lynn's War's of Louis XIV is a historian's book, and so has frustrating gaps and generalities from the point of view of use for gaming (a grand total of two battle maps, for instance, one of them Blenheim), but is a good overall work, especially for the composition of field armies and the conduct of campaigns each year. Chandler's Art of War in the Age of Marlborough actually has quite a bit of hard information on the era, and is probably the next most useful reference behind Grant as a single source, and Chandler's Atlas of Military Strategy has hard to come by battle maps for the LOA (and Turenne's campaigns as well).

Finally, for uniform information, along with unit organization, you can't go wrong with any of the Sapherson books, and the Knotel contains a surprising amount of uniform information for this era in the introductory paragraphs for armies old enough to have a history that goes back to the 17th century.

1) Barthorp, Michael. Marlborough's Army 1702-11. Osprey: London, 1988

2) Brolin, Gunnar. Swedish Mercenary Forces: War of the League of Augsburg from 18th Century Military Notes & Queries No3 found on Magweb (www.magweb.com). Partizan Press, 2001.

3) Chadwick, Frank and Novak, Greg. Volley and Bayonet. GDW, Inc: Bloomington, 1994.

4) Chandler, David G. Atlas of Military Strategy. Free Press (Macmillian): New York, 1980.

5) --. The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough. Sarpedon: New York, 1994.

6) --. The Campaigns of Napoleon. Macmillian: New York, 1966.

7) Chartrand, Rene. Louis XIV's Army. Osprey: London, 1988.

8) Childs, John (General Editor, John Keegan). Warfare in the Seventeenth Century. Cassell & Co: London, 2001.

9) --, The Nine Years' War and the British Army 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries, Manchester Univ Pr, 1991. (special thanks to Steve Darrell who so kindly forwarded me photocopied excerpts of this reference).

10) Embleton, Gerry and Tincey, John. The British Army 1660-1704. Osprey: London, 1994.

11) Gardiner, Samuel Rawson. Gardiner's Atlas of English History. Longmans, Green and Co: London, 1902.

12) Grabsic, Z and Vuksic V. The History of Cavalry (translation of Die Geschichte der Kavallerie). Facts On File, Inc: New York, 1989.

13) Grant, Charles Stewart. From Pike to Shot 1685-1720. Wargames Research Group: Lancing, 1986.

14) King, Ben. Fusil and Fortress: Being an Account of Warfare During the Time of His Grace The Duke of Marlborough. Benjamin D. King (Systems Analysis): Newport News, 1977.

15) Knotel, Richard. Uniforms of the World (1700-1937). Scribner's: New York, 1980.

16) Koch, H.W. The Rise of Modern Warfare: From the Age of Mercenaries through Napoleon. Prentice Hall: N.J., 1981.

17) Lynn, John A. The Wars of Louis XIV. Longman (Pearson Education, Ltd): London, 1999.

18) Moore, Anthony. The Army of Brandenburg Prussia 1685-1715. Gosling Press: Pontefract, undated.

19) Nafziger, George, The Nafziger Collection (17th and 18th Century Catalogs). See http://home.fuse.net/nafziger/index.html.

20) Sapherson, C.A. The British Army of William III. Partizan Press: Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, 1997.

21) Sapherson, C.A. The Danish Army]699-1715. Raider Books: Leeds, 1990.

22) --. The Dutch Army of William III. Partizan Press: Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, 1997.

23) -. The French Cavalry 1688-1715. Raider Books: Leeds, 1990.

24) --. The Imperial Cavalry 1691-1714. Partizan Press: Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, 1997.

25) --. The Imperial Infantry 1691-1714. No publication data, but probably Raider Books (as above).

26) Spindler, Martin Andrew. The Army of Hessen Kassel 1650-1700 from 18th Century Military Notes & Queries No2 found on Magweb (www.magweb.com). Partizan Press, 2001.

27) Schorr, Dan and Tyson, Mike. Dutch Colors and Standards of the War of the Austrian Succession from The Courier no 63 found on Magweb (www.magweb.com). Courier Publishing, Co, 1993.

28) Wise, Terrance and Rosignoli, Guido. Military Flags of the World 1618-1900. Arco: New York, 1978.

29) (anon.) The Blue King's Little Army: Bavaria 1680s from The Courier Vol IV No 5 found on Magweb (www.magweb.com). Courier Publishing Co, 1983.

USEFUL WEBSITES:

1) Nec Plurbis Impar (indispensable source for OOBs and information on the French Army): http://vial.jean.free.fr/new npi/

2) Daniel Schorr's Northern Wars site (much information on Danish Army and lots of other useful material that can be gleaned for LOA): http://www.megalink.net/-dschorr/

3) Keith McNelly's Volley and Bayonet Page (go here for many official and non-official revisions and updates to the VnB rules, also much good historical information interspersed): http://homepages.paradise.net.nz/mcnelly/vnb.htm

4) Warflag (many WSS flags can be applied to LOA): http://www.warflag.com/

5) The Spanish Tercios 1525-1704 (much information beyond the Tercio, to include a wealth of information on other armies, tactics, organizations, and battles, including the LOA era): http://www.geocities.com/ao 1617/TercioUK.html

6) Military History Links: http://www.newarkirregulars.org.uk/links/mhresearch.html

7) Scans of French Army Uniforms of 18th Century along with flags (which tended to not change very much): http://www.flyingpigment.com/gallery4.htm

8) Eric Veitl's Tricome page: http://pagesperso.aol.fr/ericmveitl/index.html

9) Roly Herman's 18th Cent French Army: http://dare.paradise.net.nz/france/index.htm

10) Land Forces of Britain (individual regimental histories-much good information to be gleaned here): http://www.regiments.org/milhist/index.htm

11) Army of the Duke of Savoy at Marsaglia (good site with lots of good uniform information for both the Savoy units and foreign contingents): http://members.xoom.virgilio.it/dragonirossi/albion.htm

YAHOO NEWSGROUPS

(an indispensable source of not only consultation and advice but also many, many useful files and downloads to be had):

1) Lace Wars . The Lace Wars list is devoted to Horse & Musket Wargaming, and warfare in the 18th century up until the time of the Napoleonic Wars. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/LaceWars/?yguid=86108135

2) REMPAS . A list to discuss, (Renaissance, Early Modern, Pike and Shot) http://groups.yahoo.com/group/REMPAS/?yguid=86108135

3) vnblist . Group supporting the Volley and Bayonet miniatures rules set by Chadwick and Novak: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/vnblist/?yguid=86108135

4) warflag Being a discussion arena for military vexilology, primarily for wargamers and military historians. Exchange forum for prints and other information useful for designing paper flags on computer for use with military miniatures. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/warfag/?yguid=86108135

Back to MWAN # 129 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com