I've been corresponding recently with Bob Jones, the Prophet (you can't really just call him an author) of Piquet Bob and I see eye-to-eye on several things, and we're both fond of preaching this idea of asymmetrical game structures because we find them to be superior to the old fashioned "I Go, You Go" style of game design. And then something occurred to me: we're not the revolutionaries we claim to be. We're just good at re-arranging things.

One of the recurring arguments in wargaming is this question of whether such-andsuch is a "game" or a "simulation." The implication is usually that a game places fun over historical realism, whereas a simulation places historical realism at the center, and works out from there. Obviously, this is a false dichotomy. First of all, nothing we do on a tabletop actually "simulates" anything other than moving little metal men on a tabletop. So it doesn't really matter what processes we use; we're never really simulating war. Second, the amount of fun you might obtain from playing the game is relative to the degree that the rules feel 'right' to you. There are plenty of guys who have a lot of fun with extremely detailed games. I'm not one of them, but I do recognize that for many wargamers, a simple game is no fun at all.

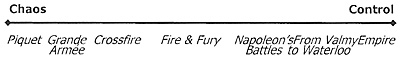

So I think a more useful set of labels would differentiate the style and approach of the game designer, rather than trying to talk about "fun" or "realism." And here I do think we can set up a kind of continuum, explaining the ways in which games work. I'll call it "Control" versus "Chaos" models of games.

So I think a more useful set of labels would differentiate the style and approach of the game designer, rather than trying to talk about "fun" or "realism." And here I do think we can set up a kind of continuum, explaining the ways in which games work. I'll call it "Control" versus "Chaos" models of games.

At the "Control" end of the continuum we have games that have some or all of the following features:

- A very detailed sequence of play.

- The ability to know what will happen next.

- Units that reliably behave the way a player wants them to.

- Many opportunities for the players to make decisions down to the smallest detail during game-play.

- Game mechanics that can be relied upon (for instance, you can always write orders every X number of minutes, or at such-and-such phase of every turn.) * Precise scales for time, distance, figure-to-man ratio, and so on.

At the "Chaos" end of the continuum the games would have an absence of those features, or features that did not allow for player knowledge or control in those ways.

I've noticed that the "simulations" guys often prefer these very detailed and predictable games where everybody knows in advance what will happen, how long it will take, what order it will come in, and so forth. In other words, they prefer an environment that was absolutely nothing like that faced by an actual commander, and yet they still see this somehow as a "simulation."

But...

The chaos games inevitably suffer from their own forms of predictability. It's only a matter of re-shaping your thinking around the new game-play, and you soon realize that these allegedly chaotic games are in fact quite predictable, too.

Take, for instance, a card-driven game like Piquet. Both players know in advance how many and what types of cards are in both players' decks; that information is part of the scenario design. Thus, if I know that my opponent only has three 'Reload' cards in his deck, and I see those three cards come up relatively early, I now have a huge advantage: I know that he can't reload again until he gets through the rest of his deck, or until there is a reshuffling. I can deliberately entice him to fire on me, setting up a situation whereby he's stuck and unable to reload and fire again when I give him a serious Whack. This isn't graduate-level card counting; it's just common sense and taking advantage of the system, the way that all human beings have always learned to take advantage of all systems.

Sequence vs. Simultaneity

In most Control-type games, the core of the system is a sequence of some sort, and that sequence does not change from one turn to another. Each turn, you know in advance that commands will come before movement, which comes before firing, which comes before melees, and so on. You know far into the future what your options will be. Furthermore, when the time comes to move, you know that you can move any and all of your units, all at this time. The Chaos-game advocates point to this and laugh, but let's be honest: there is a lot to be said for moving all your units in one swoop, especially if you have a lot of them on the table.

Most Chaos-type games, by contrast, offer you the chance to take a single "action" at a time. Those actions are usually not prejudiced in any kind of way, meaning that rallying a unit, shooting a cannon, marching down a road, or whatever, each constitute one action, and any one might be done when your opportunity comes to take an action. Sometimes (as in Piquet) chance allows you to take many actions in a row, sometimes (as in Crossfire) only one at a time. In my game Grande Armee it is possible for a variable portion of your army to be "frozen" at a given moment, either through your negligence or bad luck, even though time marches on. But a crucial problem with this kind of system is that it freezes time for all units except the one(s) currently taking action.

This is as unrealistic as any I Go / You Go model. Why should we assume, for instance, that Unit A, on one side of the field, can't move, just because Unit B, on the other side of the field, is taking an action at this moment? Why, in fact, should the action of any one unit preclude the action of any other? Furthermore, why should one type of action being carried out mean that a different type can't be carried out simultaneously elsewhere by some other unit? (Unit A is moving while Unit B, a mile away, is shooting?)

The chaos-type game has not really eliminated the I Go / You Go model; it's simply reordered it. In so doing it has solved some old problems (predictable sequence, unrealistic managements, etc) but has introduced new problems. One of these is the likelihood that one or two units in your army will do a whole lot, and a majority of others won't do much at all. In Piquet, movement is predicated upon unit type (infantry, cavalry, artillery) and/or the terrain it's currently in. Barring any special event cards, it does not appear possible for one division on one side of the table, in a forest, to move (or shoot, or whatever) at the same time as a regiment on some other side of the table, in clear terrain. In Grande Armee we may not know in advance who will move next or which forces will be activated, but we do know with a certainty that while artillery is firing, nobody else is moving. In other words, these supposedly "chaotic" games do have a logic to them - they're just alternative systems, not a real absence of system.

Now, we chaos-types are fond of pointing out that time is liquid in our games, and things should not be hamstrung by a need to explain exactly how long they took (after all, who knows), in what order they occurred, and so on. So you might hear a player saying: "Unit B isn't moving right at this moment, but the 'moment' doesn't really exist in the battle - it only exists in the game. When I get around to acting with Unit B, then it's moving. In the meantime, moving Unit A might be happening at exactly the same time."

I'm sympathetic to that way of thinking, but you can't deny that the game mechanics structure a limited number of opportunities to act, and the plain fact is that you have only so many opportunities to act, and when such an opportunity arises, your use of it for Unit A means you can't - can't, mind you - use it for Unit B. Therefore, if enough of these opportunities pass by and Unit B does nothing, it's safe to say that Unit B is stuck in time because the opportunities to act are all being given to Unit A. And that just doesn't make sense.

Incident vs. Intent:

When it comes to game design philosophy, Bob Jones and I differ in at least one major way. He sees the commander's role as dealing with a series of unpredictable incidents, trying to keep one's plan together in the face of entropy. For that reason, cards in Piquet come up, and you face only the decisions afforded by those cards at the moment you turned them up. I, by contrast, see the commander's role as dealing with a discrete amount of 'opportunity,' but being able to do whatever you like with that opportunity when you get it. For that reason, I favor a system of choice whereby you can take an action or not, limited only by the feasibility of success of whatever action you've chosen.

But in both cases, what we've done is frozen time, much in the way that the oldfashioned I Go / You Go games do. Whereas the control-type games freeze time across the whole board in predictable blocks, divided by 'phase,' we chaos-types freeze time in little packages here and there, divided by task. And I'll be the first to admit that it's not necessarily a superior form of game-management or of simulation. I like it (obviously), but it's not fool-proof as a 'better' model.

And Then Wellington Waved His Hat:

According to legend, old Arty Wellington - upon seeing the repulse of the Imperial Guard at Waterloo - waved his hat excitedly and called for a general advance all along the line. The British army began to push forward and the exhausted French collapsed.

Now, this is probably as full of holes as most of the other Waterloo legends, but it is true that the Anglo-Allied army began a general advance at the end of the battle. It surely didn't happen all at once, as the order must have taken quite a while to reach all the formations, but there was a point at which all arms - infantry, cavalry, artillery - were advancing simultaneously across a broad front of nearly three miles, causing all sorts of actions and combats, all of which happened in overlapping time, and in less than one hour, all-told.

Without giving up the advantages of the chaos-game model, we need a mechanism that will allow for that kind of simultaneity. We need some way of waving our hats and getting multiple things to happen at once. And I don't mean 'fudging' it with some flimsy argument about how time is liquid and even though this unit has been sitting here unmoved for three hours, it's actually in-motion....

So this is my new Holy Grail: the game-sequence that incorporates:

- 1) A limited and variable amount of player choices and control.

2) An unpredictable future and relatively unstructured sequence.

3) The possibility that, at times, you can do many different things at once.

Back to MWAN # 124 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com