The Indian or Great Mutiny occurred in 1857, and consumed most of northern India, including the provinces of Oudh and Bengal. This conflict between the Victorian attitudes of the European British East India Company and Her Majesty's Imperial Army, and the religious zeal and ferocity of "Hincloo" or "Musselman" mutineers and their supporters must go down as one of the most glorious, hard fought, and savagely brutal of the Victorian Era. The Great Mutiny began in a bewildering fashion with no apparent leaders or concerted action, yet it occurred in a manner that seemingly couldn't have happened without it.

The main causes seem to have been the growing attitude of East India Company officials and officers to treat the Indians as less than human (this was not the case originally) or as children who will never grow up to full adulthood, and the belief among the native soldiers and civilians that the British were out to destroy the caste of the Hindoo and make the Musselman unclean so they would have to become Christians. There were enough incidents to have given that impression to the men, yet there does not appear to have been a deliberate policy in favor of either. The British officers commanding the native regiments added to the tragedy, holding the silly belief that some other poor fellow's men might mutiny, but never would my children do such a thing. They did! With terrifying results.

Great battles, sieges, and marches abound, along with acts of tremendous bravery and incredible ferocity and barbarity. The two opposing sides fought with unbelievable savagery; no quarter being offered or given in most cases, especially after the British retook Cawnpore. The Indian Mutiny period offers excellent gaming possibilities to any wargamers of the Victorian Colonial Era. The personalities and actions are varied from a small skirmish level to the siege of Delhi, which requires some 60 to 70,000 mutineers and up to 5,000 British and Company troops. In this article, I will present an overview of this Great Mutiny and the uniforms, weapons, tactics, strategy (if there was any), and the soldiers involved (both sides - officers and men in the ranks) in an effort to explain why the period of the Great Mutiny in particular should not be overlooked by any wargamer, especially those interested in Victorian Colonial Wargames.

Drawing Up Sides; or Whom Shall I Champion Here?

Her Majesty's Imperial Forces

The British army in India was tiny at the time of the Great Mutiny, amounting to less than 5% of the total soldiery in India. Their normal establishment was low due to the Crimean War, and this was also the cause of the low number of men per battalion and the correspondingly high number of recruits in their ranks.

There were battalions of line and light infantry, Highlanders, The King's Royal Rifle Corps (60th), plus engineer and artillery detachments. The white troops did not acclimatize well in the tremendous heat of the high plains where the major actions of the Great Mutiny were to take place. Here the heat could and did exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade. The infantrymen often suffered severe burns just handling their weapons in the severe heat.

Cavalry types included dragoon guards, light dragoons, hussars, and lancers. The Cape horses from South Africa, used by much of the cavalry and artillery did not do well here. The cavalry seldom had much staying power unless mounted on native horses.

The artillery, though well served, was frequently outgunned and outnumbered by the equally well served mutineer artillery. The true plus of the Imperial troops was their firmly established corps of commissioned and non-commissioned officers, which the mutineers did not have to command their forces.

"John Company" (Her Majesty's East India Company)

The forces of the East India Company (EIC) were the predominant forces in the Great Mutiny. They were vast and varied; from sillidar horse to native sepoy and European volunteer. Cavalry consisted of three basic types:

- 1) Governor-General's Bodyguards; well trained sillidar light horse. There were three of these units Bengal, Bombay, and Madras. None of these units mutinied.

2) Light cavalry; well trained silhadars primarily raised in the provinces of Bengal and Oudh. They were dressed in European styles and almost all of these units mutinied.

3) Irregular light horse; sowar units, usually of good quality. They were predominantly armed as lancers. Several of these units mutinied and several more were disbanded, but the remainder served in the EIC forces. Skinner's Horse was originally a unit of this type.

The infantry of the EIC Army was also divided into three types:

- 1) European volunteers; not unlike the French Foreign Legion, made up of adventurers, deserters, and men trying to forget or cover up a disagreeable past. These units covered themselves in glory during the Great Mutiny.

2) Sepoy infantry; units of native Indians divided into units of either the Hindoo or Musselman. The units consisted of eight line companies and usually one rifle company. Most of these units mutinied or were disbanded, although many individual sepoys remained loyal. All these units' officers and upper level NCOs were white.

3) Irregular infantry; units of questionable value even at the best of times. Most of these collections of frontier tribesmen and vagrants disbanded of their own accord with some men joining the mutineers.

The Native Artillery was excellent, well served, and competent. They had white officers and NCOs and native gunners. Most of the gunners in the Bengal Artillery went over to the mutineers, but the whites manned the guns for the British Army.

The Mutineers and Others

The army of the Great Mutiny consisted of native troops who had mutinied against John Company. These were regular troops with good training, and were very competent in action. They had one major problem; none of them had ever held command over much more than a platoon, and even these few men never had the opportunity for independent command, instead serving under European officers and senior NCOs.

The mutineers were aided by three groups of other natives (Isn't it strange how things seem to break down into threes?):

- 1) Native princes'armies; these were seldom of great value, though some were European trained. These units were often small and reluctant to follow any orders but those of their liege lord.

2) Budmashes (or Badmashes); local villager who were commonly thieves, brigands, or self-styled toughs. These men were of limited value and were totally unable to stand in the line of battle. They were primarily useful in slaughtering helpless women, children, and injured or old men. For some strange reason, a large number of butchers seem to have joined the Budmashes.

3) Goojurs (or Gujars); highwaymen of India. These brigands often joined in for the expected plunder. They were also unruly and given to atrocities, but normally gave a better performance than the Budmashes. (Ali Baba and his 40 thieves were Goojurs.)

Mutineer artillery was numerous and well served, but they often reverted to the Indian preference for huge guns, thereby often forfeiting speed of loading for size of shot. This usually proved disastrous. The mutineer artillery was also sslow when it was limbered due to their almost exclusive use of oxen and elephants for motive power.

On the Whys and Wherefores of the Great Mutiny and How the Whole Mess Came to Be

When the first Englishman came to India he came as merchant and soldier. During the conflicts with France and the numerous warrior princes who ruled India, a bond was forged between these English adventurers and the Indian soldiers. The English were looked on as a sort of father figure, a role that many if not all of the English assumed with great relish. These English adventurers, and most of those who followed were men who didn't fit into the normal day-to-day life in England. These intrepid individuals were almost made for this new land. Many took to the life with great zeal. They took on the trappings of local religions, respected the local customs and ways, and they often took native wives (not to be done by a "true" Englishman). These men even administered local justice and even gave out death sentences without resort to local courts. This was the mark of a leader.

The situation was reciprocated by unbelievable love and respect among the sepoys of the John Company army. The sepoys venerated their commander almost as a Hindan god or Musselman angel. Englishmen could do no wrong in the eyes of the sepoys, even when giving out punishments or death sentences. The "goralogs" (white men) respected local customs and ways, and many partook of them. Sepoys referred to their commanding officers with terms meaning uncle or father, and treated them as such. The non-com missioned officers of the sepoys were venerated among their own people, for soldiering was an honorable profession. Even the retiring soldier could expect a good marriage and a comfortable life.

This mutual admiration society continued during the conquest of India. Sepoys were offered no insult to their cast and companies were kept cast similar if at all possible. No "untouchables" were accepted for military service, and few of non-soldier castes were taken. Commanding officers and European NCO's remained with the same regiment throughout their careers. These soldiers displayed a singular loyalty to their children" as they called their sepoys. But changes were in the making.

As the company grew, so also grew the need for "Company Men" and civil servants to carry out the ever expanding task of ruling this Empire. The Company offered substantial pay for these new positions and transfers from the army of young officers fresh out from England and seeking rapid advancement. This effectively robbed the army of promising young men, who might have learned from regimental commanders nearing retirement and who would soon be replaced. This chance to make one's fortune attracted an entirely different type of individual to India. These men were not sympathetic to the Indian native or the way things were done locally. These men frequently brought their wives and tried to convert India to England, a task utterly beyond anyone's capacity. They were arrogant, with airs of insufferable superiority. They flaunted their disregard of all things Indian, and often committed acts of utter stupidity when dealing with local nobles.

With these men came a new problem; Christianity of a different and aggressive form. There had been Christians in India even before the first British and French trading posts. Most Indian leaders accepted it as a full-fledged religion worthy of equal respect as Mohammedanism and Hinduism. But with the new men from England came a very aggressive form of religion. This new form brooked no opposition and was very bound up with the British form of Manifest Destiny. Sepoys were forced to suffer insult to caste and food laws by their unthinking commanders. Often "Company Men" required all native workers to be "Christian" to hold any job of importance, The power of Christianity was undermined by these methods, which led many native Indians to lie about their religion in order to work. Christianity became a religion to be feared or ridiculed, not respected as it had been prior to these changes. Many Indians came to believe that the Crown and Company were trying to forcibly change them into good little Christian soldiers. This was never the official policy, but it was the unofficial agenda of many of the new breed of Englishmen in India. Even more deadly to the Company and Crown were those men who considered the native Indians to be little more than animals. These men often went out of their way to insult and belittle the natives.

The sepoys were slow to react to this changing situation. A few regiments mutinied from time to time for various reasons. The standard reaction to mutiny was time in the guardhouse, or hard labor if some other infraction was committed as well. Indian sepoys tended to view military service in the same light as American Militia. He could go home when the family needed him and if things weren't going as he thought they should, he mutinied. He considered an act of mutiny in the same light as a twoyear old considered answering "no" to Brussels sprouts. He was simply paying off an act of breaking faith with his own act of breaking faith. The concept of irrefutable truth and honor was not a part of the Hindoo and Musselman way of life.

The "old" Englishmen accepted and worked within this framework and treated mutineers (a rarity) as recalcitrant children as the mutineers returned to camp (which usually occurred rapidly). This treatment of mutineers created a strong bond between commanders and their men. The "new" Englishmen had a completely different idea about mutineers. They hanged them; quickly and without trial in most cases. Hardly a show of compassion, understanding, or fatherliness to the sepoys, this new policy was never officially announced to the sepoys. This lead to the sepoys viewing their arrangement with the Company in a new light, and it led to more mutinies and more hangings. Additional damage was done when several regiments were ordered to ship out from India aboard ship to Persia. This would destroy the caste of these regiments. There would be no way for them to prepare their own food, or to clean their own cooking utensils, as required by the Hindoo laws. Misunderstanding followed misunderstanding, and insult followed and the problem grew. Yet the sepoys still clung to their faith in their "fathers," the regimental colonels.

The final blow to the relationship came with the announcement of the new Enfield rifle and its cartridges. Previously the sepoy made his own cartridges and knew what was in them. The Enfield cartridge would be mass manufactured, which by itself was a blow to the cast of the sepoys. When a rumor began circulating that the cartridges would be covered with cow and pig fat, an act that would destroy the Hindoo's caste and make the Mussleman unclean before Allah (it was actually mutton fat, which was offensive to neither religion), the die was cast. To this was added a rumor that when all sepoys were made unclean this way, then the Christians would force them to join their religion, and the situation took on a new urgency. It was now a war for home, hearth, and religion, always the most horrible of wars. Add to these problems the prophecy of the downfall of the English Raj in India, which was to occur 100 years after the great victory of Clive at Plassey in 1757.

The rumors ran rampant in the regiments of Bengal and Oudh as the disaffected and bewildered sepoys listened to tales of the horrible things their English masters planned for them. Dervishes and prophets arose everywhere. The native population was also aroused by the tales and prepared for the fall of the Raj. Chupattis (small hard cakes of rice) were passed from village to village, but no one central agent of the unrest could be found. The English were perplexed. Some understood there was something wrong, but no one could figure out what it was.

The English regimental commanders (and possibly others as well) refused to countenance the possibility that their regiment might mutiny. Maybe some other colonel's men might do so, but "never my children." The government officials seldom knew enough about local customs and lifestyle to even have an inkling of what was about to occur. And when it did occur, the shock was enormous.

The actual start of the Great Mutiny was at Meerut. A group of sepoys had tried to mutiny, but were stopped by British troops. A sepoy, Manguel Pandy (from whence comes the nickname of the mutineers Pandies) fired a rifle and wounded a white officer. He was hanged. Several days later men of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry refused to handle the Enfield cartridges and were jailed. The other men of this regiment moved to free the jailed men. The other native regiments of infantry and cavalry rallied to the aid of the 3rd BLC. As this occurred, the Budmashes and Goojurs of the town erupted in a frenzy of killing. The situation would have been worse if the 60th Rifles hadn't delayed Vespers call, due to the heat, by one hour. They were supposed to be in church as the mutiny broke out, but they weren't much to the dismay of the mutineers. The rebels proceeded to march on Delhi demanding the 82-year old king of Delhi become their leader. Delhi soon became a bloodbath also.

Even as the bloody sepoys attacked them, most Englishmen and women stood about in shock at what was happening to them. Some even attempted to order the blood-crazed rebels to cease and desist their actions.

The atrocities committed were acts of bestial fury and a misplaced religious hate that erupted and found no authority to direct its course. Things were done that were almost too foul to be mentioned. These acts were reciprocated by British soldiers later in the reconquest of Bengal and Oudh. The general effect of the atrocities was to galvanize the home population of Britain into a decisive action. The mutiny was begun and its ending would be a long and brutal affair.

The Nature of Names and the General Look of the Army of Her Majesty Queen Victoria I and John Company in India

This section will cover some important terminology and basic uniform information for the Great (or Indian) Mutiny.

Terminology

There are a number of terms that will require definition for many readers. The following summary should help. Silhadar Horse - Also know as sillidar or silhodur, these fine horsemen supplied their own horses and were often semi-mercenary at best. Sowar Horse - These men had their horses provided to them by the employer. All British raised native cavalry units, except for native irregular cavalry, were of this type. Sowar became common usage for all Indian cavalrymen in British service. Budmash - The market toughs and thieves of India. These people quickly joined the mutineers and were most likely responsible for the greatest number of atrocities, either by direct action or by instigation of the mutineers. Primary arms were a stick or sword. Goojura (or Goojars, Gujars) - Mounted bandits living off the Indian countryside. Goojurs also joined the mutineers with great abandon, and like budmashes were to cause many atrocities and seldom, if ever, fought with any bravery or honor.

Uniform Notes - British & Loyal Troops of the Indian Mutiny

British dress uniforms consisted of a red wool, hip length coat with pointed cuff in the regimental color and white trim. Trousers were blue-black (more black), also of wool with a 1 1/2 inch red stripe down the outer seam. A round pillbox cap with white trim, and short black boots with anklets completed the uniform. All belts were white, with a black cartridge box in the rear. Waist belts were common. Haversacks were used by most men on campaign. The canteen was replaced by a blue water bottle of local Indian make. All non-officer ranks carried the standard issue muzzle loading musket, which was being replaced by the Enfield Rifled Musket even as the Great Mutiny started.

Officers carried a variety of personally obtained weapons, consisting normally of a revolver and a sword. Some officers carried a carbine or a shotgun. The dress uniform was worn by the 75 th Regiment of Foot during the entire Mutiny and by several other formation at one time or another.

The highlanders wore a similar uniform, but the coatee was cut shorter. Trousers were replaced by a plaid kilt and diced stockings. Spats were worn with low cut shoes. Headgear was the same diced, feathered bonnet worn in the Napoleonic Wars.

The King's Royal Rifle Corps (60th Regiment of Foot) wore a uniform of similar cut and fabric to the line regiments, but was entirely of rifle green (in the mutiny, this quickly became a charcoal gray with deep olive tint), black collar, cuffs, and frogging and no trim. The Rifles wore this uniform exclusively during the entire mutiny. The regiment was the most proficient with the new Enfields because the Rifles were the first to receive the new rifle.

The Naval contingent, who accompanied the siege train and guns to Delhi, wore blue tunics with white tallywhackers, trimmed in medium blue, and white bell-bottom trousers. All belts, equipment, and shoes were of black leather. A straw wide-brimmed hat with a black ribbon bearing the ship's name around the crown topped off the uniform. Naval officers wore a long navy blue frock coat, white trousers, and a wicker helmet. Officers carried a revolver and a sword. All other ranks carried the Enfield rifle and a sword bayonet.

European Volunteer Regiments wore uniforms of similar cut to British troops. The men were usually veterans. Although off less discipline in parade ground maneuvers, they performed with excellence on campaign, particularly the Bengal regiments.

In the mutiny, most regiments wore the undress whites cut similarly to the dress uniform but without trim. These were usually dyed "kharkee" (meaning dust in Persian), a shade that varied from pale yellow-cream color to slate gray. The shade of kharkee depended on the dying agent used (anything from dust to tea). This color was seldom even close to uniform, even within the same company - not to mention the entire regiment.

British cavalry usually wore undress whites, but a few dyed them due to a generally more nit-picking attitude among their commanding officers. The 6 th Dragoon Guards wore their dark blue wool uniform and unlined brass helmet throughout the mutiny (leading to large numbers of men being unfit for duty due to burns on the forehead). The 10th Hussars and the 17 th Lancers wore the blue fatigue uniforms and white covers over their headgear. Light Dragoon Regiments wore an unusual tall kepi. This was normally covered with a padded cover without a havelock (a white cloth that covered the cap and hung down the neck to the shoulder of the wearer).

The European Volunteer Regiments wore kharkee and often resembled late ACW Confederate units in general appearance. The notable exception was "Neill's Bluecaps," better known as the 1st Bengal Fusiliers. The nickname came from their havelocks (designed by Gen. Henry Havelock) being various shades of blue; no white being available when they left to join the army.

Headgear took several forms, most common being the field cap, which resembled the Kilmarnock cap of the later Gurkha regiments. This was normally covered by a havelock. Some field caps had a visor attached. Also worn were wideawake hats of cloth or wicker, which resembled a straw hat worn by vaudeville soft-shoe men. The Rifles and Neill's Bluecaps wore the odd high kepi also seen on the light dragoons. No cover was worn by the Rifles. Slouch hats of ACW fame, kepis, and a wicker helmet similar to the later cork helmet but with a central ridge on the crest that was open at the front acting as a heat duct finish out the list of headgear.

Dress Uniform Colors of European Volunteer Regiments

All coats were red. Headgear consisted of the standard Kilmarnock style cap. All belts were to be white. Other details are presented in the following table.

| Battalion | Facings | Lace | Trousers | Havelock |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Bengal | Sky blue | Gold | White | White |

| 1st Bengal Light | Dark blue | Gold | White | White |

| 1st Bengal Fusiliers | Dark blue | Gold | Navy blue | Blue |

| 2nd Bengal Fusilier | White | Gold | White | White |

| 3rd Bengal Light | White | Gold | White | White |

| 1st Madras | White | Gold | Black | White |

| 1st Madras Fusilier | Dark blue | Gold | Black | White |

| 2nd Madras Light | Pale buff | Gold | Black | White |

| 3rd Madras | Pale yellow | Gold | Black | White |

| 1st Bombay | Dark blue | Gold | White | Buff |

| 1st Bombay Fusilier | Dark blue | Gold | White | Buff |

| 2nd Bombay Light | Pale buff | Gold | White | Buff |

| 3rd Bombay | Pale yellow | Gold | White | Buff |

Loyal Native Regiments in the Service of Great Britain

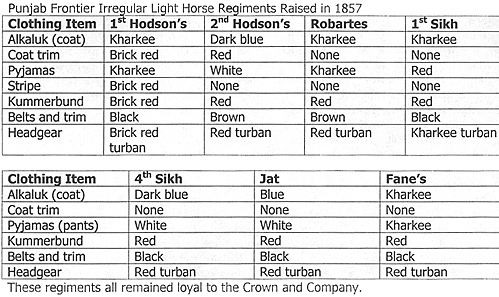

The native regiments of Bombay and Madras Presidencies remained loyal to the company, but few men were sent to put down the mutiny. On the other hand, large numbers of Sikh, Punjab, Jat, Rajput, and Pathan units were raised and sent to quell the unrest in Bengal and Dudh Provinces. The major reason for this was a longstanding hatred of these races for Bengalis. These races would have little or no objection to the grease of the Enfield rifle cartridges. These warrior people proved invaluable in the Great Mutiny, and many horse and infantry units were raised to assist those units already in service along the Afghanistan frontier.

The standard dress of these units was kharkee. Clothing normally consisted of a colored turban (anything from white to red to blue to kharkee), a loose-fitting pullover tunic with open neck (called an alkaluk), a loose-fitting knee-length pair of puttees (cloth wrappings), and slippers (chapplis) for footwear. All belts and equipment were brown or black. The regiments carried the older pattern muzzleloaders, but some Sikh units carried the new Enfield rifles.

Three of the Sikh regiments' uniforms had considerable variation from the normal style. Hodson's Horse (Corps of Guides) wore kharkee, but also wore a red turban, cuffs, trim, and sash. This unit carried the Enfield carbine. The Ist Sikh Regiment (Coke's Rifles) wore a dark blue uniform with black cuffs and trim. The turban was an absolute riot of colors. The 2nd Sikh Regiment wore a red coat, ankle-length white trousers, and red turban. Both of these regiments used the Enfield rifle.

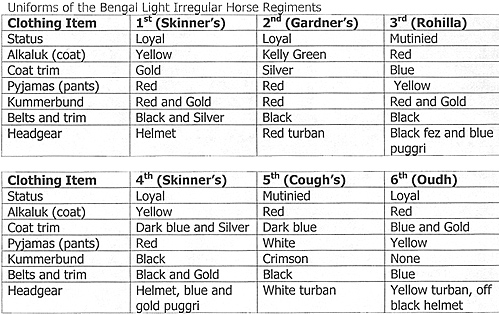

The 1st and 4 th Bengal Irregular Light Cavalry Regiments (Skinner's Horse) wore bright yellow alkaluks, bright red trousers with yellow trim, and red sashes. Skinner's Horse wore a skullcap-type helmet with a small silver cross atop a wire in the front (about 6 inches in height). The 1st Regiment's helmet had a trim of black fur. The 3rd Regiment's helmet had a blue and gold puggril. These regiments were lance and carbine armed.

The Bombay Regiments wore a standard native regiment uniform of red coatee with tails and white turnbacks, yellow collar and cuffs with gold cuff flap. Trousers were blue (or white in summer) with a one and a half inch wide yellow stripe on the outer seam. Belts were white with a black cartridge box. The blue water bottle and a brass Iota (drinking bowl) completed the attire. Headgear was either a tall peakless shako or, more commonly, the black kilmarnock cap with a two inch blue stripe around the base. All men were armed with the muzzleloader.

The Madras native regiments wore the same native regiment uniform coat as the Bombay troops. Trousers were knee-length, black, and baggy. No coverings were worn normally on the lower legs. The headgear was a strange shako thing that resembled a chefs hat with a brass or black fish-mouth ball on top. This was made of cloth or hide stretched over a wicker frame. Few units from this presidency were sent to aid in the quelling of the mutiny.

The Native Light Cavalry Regiments wore a tight-fitting uniform of French Blue (a pale blue-gray) trimmed in black. High black boots and a dark blue over black Kilmarnock completed the Bombay regiments. The Madras regiments wore short black boots and a shako like the infantry with a diagonal stripe of white-trimmed light blue from high right to low left.

The Native Irregular Light Horse Regiments wore the native costume of alkaluk, pyjamas, kummerbund, (a wide tight sash), and a turban. These units were lance armed and carried carbines and scimitars. Excellent horsemen, all were Sillidar horse.

The Native Artillerymen wore white or kharkee undress uniforms. Headgear was either a turban of the same color or the regular cap covered in a Havelock and usually worn with puggri. White officers and gun captains normally wore a dress blue coat and white trousers of the Bengal Artillery Regiments. All equipment was painted gray, and quickly faded.

Making an End. A Compendium of Items Both Lost and Found, and a Few Notes on the Leading Players in this Great Drama of Life and Death in Bengal and Oudh

During the Great Mutiny, the instance of a complete regiment of the Queen's Army (the common name applied to British Units) being at the same battle was rare. The "Armies" that were fielded by John Company were normally composed of whatever was to hand or could be raised and consolidated in a hurry. The entire cavalry force defending Lucknow was made up of the Officers of Bengal regiments that had mutinied and local British civilians who owned or could acquire a mount. There was a similar force with the besieging forces at Delhi. The 60th Rifles (KRRC) fielded the most complete force in the Delhi Field Force with 6 later 7 - of its companies present. The 75 th foot, the Sirmoor Battalion (the 2nd Goorkha Regiment), and the 6 th Dragoon Guards fielded nearly complete units. Only those forces that arrived later, such as the Sikh and Punjab Field Force regiments, would be fielding a nearly full compliment. Even the 91st Highlanders had two companies retained in Calcutta to protect the British civilians there.

Any wargamer presenting a game for his fellows would be entirely justified in presenting a wide selection of troops and types. When on is selecting forces for the Pandies, the units could, and probably should, be of varying sizes, as there was no standard unit organization above platoon and company level. Often the Pandies simply followed the leader of their choice. Local militia forces and the retinues of local chieftains would be more regularly organized, but would be of lesser morale.

British leaders tended to be intelligent and rather intrepid if in independent command, but often in conflict if in a command with other officers of similar rank, especially if one happened to be a Queen's officer and the other a John Company officer. A Queen's officer would technically outrank the John Company officer, but often they would end up in a feud or separate into two independent commands. The original delay that allowed the mutineer regiments at Meerut to march to Delhi was a conflict over whether the Queen's officer present on the parade ground was in command or if the ranking general (a rather useless overly rotund fellow, not unlike the US General Taft) who was not anywhere to be found was in command because the orders stated that "the ranking officer present should take the command and move immediately to halt the regiments which had mutinied." The Queen's officer present decided that since the senior general was "present," even though he could not be found, he was in charge. It would be three hours before the ranking general showed up, and he would not budge for three days! So much for moving immediately to halt the mutiny.

The difficulties between General Havelock and Sir James Outram, his senior commander, were also a cause for great distress. General Havelock was the commander of the relief force sent to relieve Lucknow. Sir James had been appointed to command the forces in Bengal and Oudh, but didn't reach the field army for several weeks, during which time Havelock won several impressive victories. Sir James assured General Havelock the he, sir James, would in no way interfere with the direct handling of the field army. He, Sir James, would only conduct the overall strategy of the reconquest of the provinces. He promptly set about overruling and countermanding everything General Havelock did. This lead to a direct conflict between the two, all done with perfect civility, which left Sir James irritated with General Havelock and General Havelock disheartened and all but broken. Major Harry Havelock (General Havelock's son serving under General Havelock in the field) was livid and lost no opportunity to vilify Sir James Outram regardless of the time, place, or persons present. Needless to say, this led to indecision and lack of purpose and resolve in the army.

Similar situations arose in the Delhi Field Force, most prominently between each and every one of the senior commanders and General Niell, who was perhaps the epitome of the Victorian "Christian" General. This man was all in favor of "killing every one of the black buggers" and his troops, raised in Punjab and the Frontier, seldom took prisoners. This attitude was made even worse because these troops were of Sikh, Afridi, Wasiri and other Northwest Frontier tribal stock, all of whom had a long and bloody history of fighting the Bengali and Oudh races. This bickering ended with the death of General Niell (in true Victorian style) during the taking of Delhi by storm. General Niell led his column into the city and was fatally shot during the bloody fighting in the streets. He lingered for some time, long enough to hear that the assault was successful. He died without complaint, although the wound was on that would have been very painful.

Other major figures of the British in India would be the Lawrence brothers (no known relationship to your author): Henry (Governor of Lucknow and commander of the siege until killed by a cannonball), and his brother, John, Commissioner of the Punjab, who raised and led forces to the Delhi Field Force. On the Mutineer side would be mostly individuals like Nana Sahib, a disgruntled middle rank Hindu noble of questionable parentage who perpetrated the massacre at Cawnpore, and the 84-year old nearly senile King of Delhi and his pompous sons who had absolutely no military ability whatsoever.

This concludes the series on the Great Mutiny. I hope that this will spark interest in this interesting and colorful period among the gaming community. Hopefully I have not bored anyone these articles have done some good. Until next time, God Bless, Happy Trails, and Ya'll come, Ya heyah!

Back to MWAN #117 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com