Wargamers know about Guadalcanal, but where the heck is Buna? Well, the marines get all the glory sometimes. While the marines and navy were conducting a furious and desperate battle for the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomons, the army's 32nd Infantry Division and various Australian formations were deadlocked in struggle for the eastern end of New Guinea.

Following Pearl Harbor, the Japanese seized the Australian base at Rabaul in New Britain as well as ports on the northern shore of eastern New Guinea. The eastern end of New Guinea is dominated by the Owen Stanley mountain range, which neatly separates the northern from southern parts. Along the southern shore lay the Japanese objective, the Australian base at Port Moresby. If the Japanese occupied Port Moresby, they would have a handy base from which to attack northern Australia itself The allies needed this base to support operations to clear the immense island of New Guinea of the Japanese,

Following the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, the Japanese decided on a land approach from newly seized bases at Buna and Gona on the northern shore. From there, Japanese infantry proceeded south along the infamous Kakoda Trail which linked Buna to Port Moresby, only 70 air miles away. The Kakoda Trail was nothing more than a track winding through dense jungle, over rugged ridge lines, across broken plateaus, and finally over the crest of the Owen Stanley itself. Carrying ammunition and supplies by mule and on theiFown backs, both the Japanese and Australians exhausted themselves in the fighting. Finally, by September 1942 the Japanese could no longer sustain their advance over the mountains. It was time for the allied counteroffensive to remove their enemy from Buna and Gona.

The American formation selected for this mission was the 32nd Division, originally a national guard unit from Wisconsin and Michigan. The 32nd needed thousands of draftees to bring it up to strength just before it deployed to Australia for training. The training was insufficient in many regards and as a result, the troops were quite unprepared to be thrown into New Guinea. Nonetheless, several infantry battalions found themselves struggling through the jungle tracks and up and over the mountains. Eventually an airfield was opened on the northern side of the mountains and some units were flown there and completed the march to Buna on foot Attempts to resupply the troops who made it to the northern shore by sea proved difficult at best in the face of sporadic air attack. Except for a few 75mm guns and a single 105, the artillery was left behind. As the Americans closed in on Buna, it was clear to all that this would be largely an infantry brawl in the jungle.

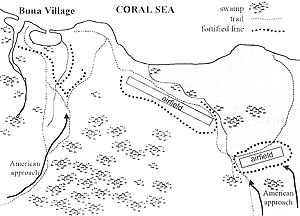

The Japanese had plenty of time to fortify Buna and its two airfields. The extensive swamps surrounding the Japanese camp defined narrow corridors along which the attack must proceed. The dry land was covered by either coconut groves, undergrowth, or high grass. The Japanese built large numbers of sturdy bunkers. These bunkers were constructed mostly of coconut logs reinforced with sand-filled oil drums and ammunition crates or even steel sheet. The Japanese defenders selectively cut down trees along the field of fire from the gun ports of the bunkers. After a few months, these Sectors of fire and the bunkers themselves were overgrown with vegetation. Thus, when the American infantry approached, the bunkers were so well camouflaged that the Japanese almost always got the opening shots at very close range. Augmenting the bunkers were numerous snipers up in the coconut trees who harassed the attackers while remaining fairly well concealed. The map illustrates the terrain.

On the map at right, the swamps are virtually impassable. The open areas, remember, are covered in coconut groves and/or high grasses so it is difficult going. The fortified lines represent the most heavily defended Japanese zones but the Japanese had bunkers and smaller defensive positions throughout the area between Buna Village and both airfields as well as along the coast.

On the map at right, the swamps are virtually impassable. The open areas, remember, are covered in coconut groves and/or high grasses so it is difficult going. The fortified lines represent the most heavily defended Japanese zones but the Japanese had bunkers and smaller defensive positions throughout the area between Buna Village and both airfields as well as along the coast.

American and Australian attacks started in mid November and lasted until the first week in January. The American force which arrived at the Buna defenses was physically exhausted. Some weak tactics and lack of artillery and air support as well as poor training and inexperience in jungle fighting led to dismal failures of the initial assaults. General Dougglas MacArthur, who had an incorrect view of the circumstances, sent a corps commander, Robert Eichelberger, to take command at Buna and get the army advancing. Eichelberger led from the front, a risky option considering the number of snipers, But Eichelberger saw the problem as one of lack of leadership and he meant to lead by example. He fired commanders lacking in energy and replaced them with fighters. He stared night time patrolling. He un-mixed units that had become mixed during the first attacks. He also got some air and artillery support although there was great difficulty in directing pilots to correct targets in the jungle or in spotting and adjusting artillery fire.

As the men caught hold of the warrior spirit, they used their initiative in the assault. In a few instances, American platoons managed to infiltrate through the fortified lines and set up positions within the Japanese-held area. Nonetheless, much of the credit for the Allied victory goes to Eichelberger.

Without setting forth a detailed description of the long battle, I want to share an idea on how to solo warigame a battle against bunkers in the jungle. Follow this line of thought, if you will. Imagine a squad of soldiers creeping through the jungle looking for the Japanese front lines. The squad is moving in single file, each soldier walking four or five yards behind the soldier in front of him. Off to the flanks, they can hear but cannot see the other squads ill their platoon or the adjacent company. From time to time, a sniper fires from the top of a coconut tree. After much difficulty and expenditure of ammunition, the soldiers on the ground eliminate the sniper and hopefully haven't lost too many of their own doing so.

Suddenly, Braaaapppp!!!! Hot lead from a light machine gun screams through the Squad. It originates from what looks like a pile of debris on the jungle floor. The soldiers hit the ground. They return fire while the squad leader tries to figure out who got hit and what to do.

While some soldiers use fire and movement to get to the side of the firing, others crawl into areas or rush behind a large tree. Meanwhile, a brave soldier or two attempts to find the wounded and drag them to safety. If he's still alive, the squad leader issues orders that send his men closer to the bunker. He knows that it will be very difficult indeed to get sufficient fire through the narrow vision slits even if he could identify them. His men are within twenty vards of the bunker, moving from tree to tree, trying to get out of the field of fire of that machinegun. But single shots are ringing out too. Another sniper is close by.

After what seems like hours, two soldiers are against the bunker, feeling their way toward the firing port, while some other soldiers place accurate fire near the opening where the bullets appear to be coming from. Supporting fire dies down as the men attempt to toss hand grenades into the opening. If all goes well, the grenade does not bounce back out but instead rolls into the bunker and detonates, taking out a Japanese soldier or two inside. The men work their way around the bunker, locating firing ports and repeating the grenade attacks. Eventually, they find a door in the rear of the bunker. More grenades! The door is blown in and the last defender fires until he is silenced. The squad leader counts his casualties. Too many. He sends word back to the platoon leader who sends another squad forward and the sequence continues.

This was bustin' bunkers the hard way. Eventually flame throwers, satchel charges, and bangalores would be standard equipment, but not so for the boys of Buna. And if the Japanese designed the system correctly, as an American worked his way into the dead space of one bunker, he moved into the field of fire of an adjacent, equally well-camouflaged bunker.

Simulate the Tactical Fight

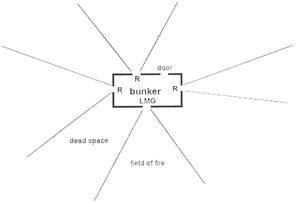

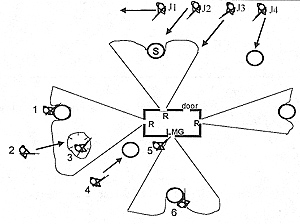

So, how does one simulate this tactical fight? Well, I worked on a design that covers most of the bases. After much thought, I decided to design each bunker on a sheet of 8 1/2 x 11 paper. The graphic shows a single bunker drawn on a sheet of paper. The bunker has firing ports on all four sides but only one contains a light machine gun, the rest are manned by riflemen. Notice that each firing port has a well-defined field of fire. These sectors can be up to 45 degrees wide but narrower is probably more accurate. The bunkers were several feet thick and the firing slits fairly small so I suspect there was a lot of dead space around the bunker, I actually tape these sheets of paper to the wargame table which isn't visually pleasing but it is important to have the fields of fire permanently marked so I don't keep trying to measure them. I use HO scale figures which pretty well support the kinds of troops I need. You can also add some kind of bunker replica and certainly some vegetation but that is more for looks than for practical use in the game.

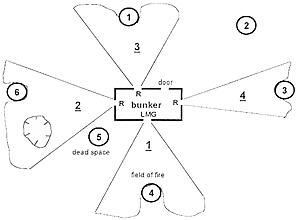

Now, what you see at right is a generic bunker. I photocopy this and then I modify them to come up with a batch of individualized bunkers. First, I add trees - trees that were large enough to provide cover for at least one soldier and also to conceal a Japanese sniper up top for my purposes, I use up to 6 trees per bunker and number them. Then I can roll a 1D6 to see which tree is hiding a sniper.

Now, what you see at right is a generic bunker. I photocopy this and then I modify them to come up with a batch of individualized bunkers. First, I add trees - trees that were large enough to provide cover for at least one soldier and also to conceal a Japanese sniper up top for my purposes, I use up to 6 trees per bunker and number them. Then I can roll a 1D6 to see which tree is hiding a sniper.

It might be a good time to discuss the difference between cover and concealment. Cover is protection from fire. An infantryman behind one of these coconut trees is protected from fire from the bunker. Concealment means only that the target can not be seen from a particular direction. For example, an American in the dead space is concealed from the bunker but perhaps not from a sniper up above him or from a Japanese patrol moving to protect the bunker from the outside. Also, remember that the jungle continued to grow after the bunkers were completed so there is a lot of tall grass even in the field of fire which call conceal a soldier but not protect him from a burst of machinegun fire sent his way, even if the fire can not see his target. You get the picture.

Next I add a depression or two. The depressions are low places on the jungle floot that both conceal and cover up to two soldiers lying prone in them. If the soldiers crawl to the lip of the depression in order to observe or to fire, then they give up some protection. Then I draw a perimeter that firmly establishes the area within which the Japanese in the bunker can observe well enough to bring accurate fire upon an exposed target. All the area outside this perimeter is dead space. Either it is outside the field of view of the firing ports or it is so overgrown with grass and trees that an attacker can move through it without being seen at all from the bunker.

Lastly, I add numbers I through 4 to the fields of fire. This is to orient the bunker once an American infantryman comes under fire. Here's what a modified bunker looks like.

Lastly, I add numbers I through 4 to the fields of fire. This is to orient the bunker once an American infantryman comes under fire. Here's what a modified bunker looks like.

Now we are ready to play. First, form a platoon of American infantry. I Use four squads and a small leadership section. I have each squad in single file with figures 1 inch away from one another. Two squads lead and two follow with the leadership section in the middle. Each squad is about 8 inches away from its neighboring squads. The platoon's mission is to clear every bunker in a zone the length of the short table. As the squads proceed forward, I roll a 1D6 each turn. Upon a result of 6, the lead soldier in a squad (the point man) is taken under fire from a bunker. Roll for which of the two forward squads came under fire.

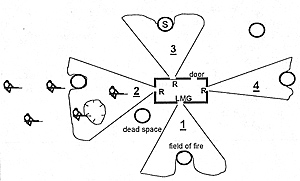

Now, place the sheet of paper with the bunker on the wargame table and orient it. Now, the soldier who was fired upon is assumed to have been standing in the middle of one of the bunker's fields of fire. Roll 1D4 to see which field of fire. Let's say the roll was a 2. So, put the lead soldier in the middle of field of fire 2. I then roll to see which tree the sniper is in. I rolled a 1 and mark that tree as having a sniper. The soldiers following are 1 inch apart so only two are in the field of fire. That means that these are the only soldiers who can now identify the bunker. Now our wargame table looks something like this below, Now we roll to see if that lead soldier was hit. I don't play this like a skirmish game and distinguish between wounded and killed but certainly you can do so. In my rules, if a soldier is hit, he is out of the action.

Now let's see some movement and fire rules. These are the ones I use but obviously your own rules make as much sense.

Movement

Movement

Soldier can get up from prone position, rush I inch, and drop down to the prone ill a single turn. Soldiers not in contact with the bunker can move 2 inches per turn until they come under fire.

Firing

Firing is simultaneous. The Japanese in the bunker fire automatically whenever all American pops up and rushes as long as at least part of the move is in the field of fire. They call also fire at any prone American who has fired at them. The Americans can always fire from the prone but cannot fire while moving. (They can of course, but it is too inaccurate to even be worth dicing for). The sniper can fire at any target, moving or prone, within his view. The bunker conceals any American standing alongside it on an opposite side from the sniper A soldier can peek around a tree or up from a depression to fire but is then subject to return fire that turn American fire at the bunker is ineffective unless the soldier is standing right next to the firing port and is firing directly into the bunker.

The bunker can only fire upon targets within its field of view. All outside the bunker call see and hit targets within 4 inches.

I use simple firing tables. Light machine gun and sniper hits any target on a 6. For rifles, roll 2D6. If one die is a 6 and the other is an even number, score a hit.

Grenades

I don't like bookkeeping so I assume each soldier carries enough grenades to make one attack. A soldier situated alongside a firing port can attack whoever is manning the firing port. A successful attack is scored 50% of the time. Likewise, an attack upon a door blows the door in 50% of the time. Once the door is blown in, a second soldier can make a grenade attack and hits all occupants 100% of the time. Or, one soldier each turn can fire into the bunker and hit one occupant with 33 1/3 % odds. I don't use figures inside the bunker, I just mark the sheet of paper when an occupant is out of action.

Now, you are saying to yourself, all the Americans have to do is to move out of the field of fire of the bunker, eliminate the sniper, move to a firing port or the rear door and attack it with grenades. However, the Japanese have thought of this and they have small roving patrols that move to defend a bunker once the firing starts. Each turn, roll a 1D6. On a roll of 6, a Japanese patrol of four riflemen appears on the edge of the sheet of paper at the rear of the bunker and enter the battle using the same rules as the American infantry. Now let the firefight begin.

Here is in example of a turn of combat.

Here is in example of a turn of combat.

Starting with American infantryman number 1. This soldier is firing at the sniper, who is within 4 inches. American number 2 is moving and can't fire. He will end his turn prone in the depression. Number 3 is also firing at the sniper. Number 4 is moving so can't fire and will end his turn behind the tree in the dead space of the bunker. Number 5 has two options. He can fire into the slit with a 1/33 chance of taking out one of the two machinegun crewmen. Or, he can make one grenade attack with a 50% chance of knocking out the machinegun and both crewmen.

Of course, he can only make one grenade attack so if he fails, he must revert to rifle fire only. American number 6 has no targets within range.

Now for the defenders, The rifleman in the bunker can fire at the soldier in the depression (# 3) as well as the soldier running toward the depression (# 2). However, the American number 1 is concealed from his view. The sniper can fire at numbers 1, 2, and 3 and 4 (because numbers 3 and 4 started out of range but ended in range). The sniper can not fire at number 5 because he is covered by the bunker nor number 6 because he is out of range. The light machine gunner can fire at either 5 or 6 with the same odds. This is because number 5 can not be seen except for the split second when he either throws grenades into the slit or fires a single shot at point blank range between machinegun bursts. None of the Japanese infantry can fire, only because all targets are out of range even at the end of their moves.

Once you have the basics down, how can you further add realism to/complicate the game? Well, some of the American and Japanese infantry will carry automatic weapons, perhaps one per squad. Make up some good odds for them. Likewise, you can add flame throwers and satchel charges to the American squads, again, only one per squad. In my rules, the sniper reveals himself and becomes a target as soon as he fires. I have also thought of having the Americans roll for spotting the sniper or not. Maybe because they are focused on the bunker and they can't get a good fix on the sniper immediately.

In my rules, I only send one Japanese patrol to support a bunker. If you want to really create carnage, keep rolling for Japanese reinforcements every turn. Another trick would be to add mortar fire. The Japanese reinforcements can roll to see if they brought a knee mortar with them. If so, they have an indirect fire weapon that can hit anything the crew can see. They call also fire directly on and around the bunker to clear it of any Americans against its walls. Give the American platoon a light mortar. It can pin down reinforcing Japanese infantry but has no appreciable effect on the snipers or the bunkers.

So, we have looked at one squad attacking one bunker. However, the bunkers were constructed, at least in the heavily fortified areas, to have interlocking fires. This ineant that the dead space of one bunker was in the field of fire of another bunker. To do this, once all American enters the dead space between fields of fire, roll a die. There is a 1/3 chance that thal dead space is covered by another bunker. If so, then place the second bunker so that one has fields of fire overlaps the dead space. Now the battlefield stars getting crowded and the American difficulty increases geometrically (kind of like the real battle).

And remember, there are three other American squads in that platoon. Once one squad cornes under fire, the other squads move 2 inches per turn to join the battle. After a bunker is cleared, the platoon leader reorganizes his people and starts out again. The fun thing is that each fight for a bunker is different than the one before because of all the variables such as the orientation of the bunker, the location of the sniper, and the presence or absence of Japanese reinforcements.

Bunker fighting was a real meat grinder. The warrior spirit of the Japanese infantry meant no retreat, no surrender. The Americans and Australians paid in heavy casualties every step of the way through the Japanese fortified zones.

This game is particularly adaptable because it can be played on a pretty small Surface and one can use markers instead of figures if need be. It is also amenable to any number of modifications of its rules to suit the notions of the solo gamer.

Editor's Note. I want to thank Rich for doing this article. He didn't know it when he wrote it, but my 84-year old father was at Buna with the 32nd infantry Division as a NCO in a rifle squad. Upon receiving the arlicle, I sent it off to my Dad who really enjoyed it.

When I was home several weeks ago, we spent some enjoyable time discussing it and he showed me where he was during the battle. He and I talked at length about New Guinea in the past, but it was something special this time. Thanks, Rich!.

Back to MWAN #116 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com