In late June 2001 I conducted a seven-day, self-guided driving tour of Indian Wars and other Western history sites in the upper plains/mountain region of the United States (to include northern and eastern Wyoming, western South Dakota, and adjacent areas of Nebraska and Montana). As an aid to the wargamer interested in this period of history, this two-part article rates each of the 16 major sites I visited in terms of:

In late June 2001 I conducted a seven-day, self-guided driving tour of Indian Wars and other Western history sites in the upper plains/mountain region of the United States (to include northern and eastern Wyoming, western South Dakota, and adjacent areas of Nebraska and Montana). As an aid to the wargamer interested in this period of history, this two-part article rates each of the 16 major sites I visited in terms of:

- 1) its relevance to the Indian Wars and/or the era of major Western settlement (ca. 1850-1880);

2) quality of interpretation and facilities of interest to the historical gaming community, and

3) overall quality of the experience ("worth-whileness") for the potential visitor. Ratings run from one ace (*), meaning the worst, to four aces (a don't-miss site).

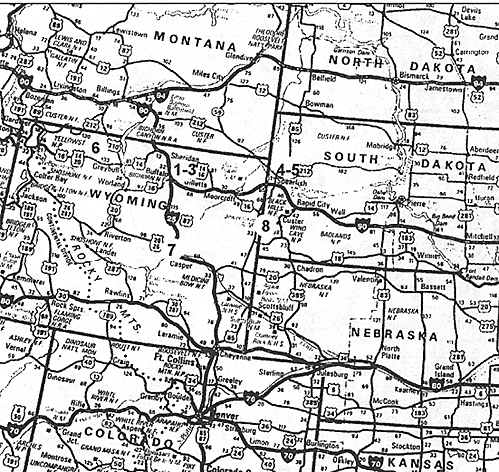

The general location of each site can be found on this Rand McNally road map: numbers thereon correspond to the order in which the sites are reviewed below. The reader interested in putting together a tour of his or her own is encouraged to research specifics such as street addresses, hours of operation, admission fees, etc., in one of the many available hardcopy travel guides, in materials provided by the relevant Chambers of Commerce, or on the Worldwide Web.

So what am I, your personal travel agent, you should have such information at your fingertips? You could look inside a book better. A decent one is A Guide to the Indian Wars of the West, by John McDermott (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1998). And one more thing: WAKE UP! You still play with TOY SOLDIERS, for goodness sake! Don't you know you're breaking your father's heart? Don't start with that Mr. Fancy "if-you-only-knew-how-much-these-things-were-worth" nonsense. Dust collectors, all of 'em! As soon as you've gone away to school, I'm tossing 'em into the garbage, so help me! Because of you I'm ashamed we should even invite your second cousin Heidi over, she's so nice.

1. FORT PHILIP KEARNY, WY (***)

Ft. Kearny (pron. KAR nee) was the centerpiece of Red Cloud's campaign to close the Bozeman Trail, 1866-68: the only Indian War actually won by the Indians. The post's first commander, a book learned colonel named Henry B. Carrington, seemed to be much more interested in executing his elaborate architectural plan (apparently aimed at bringing into being the "model frontier fort") than he was in chastising Indian depredations. To be fair, Carrington was hamstrung both by contradictory policy from Washington (where advocates of peace and war held sway alternately), and by lack of men. The latter was especially true after one of his headstrong subordinates threw away a third of the post's fighting strength in the infamous "Fetterman Massacre" of late 1866: see 2. below). The post was effectively under siege by the Indians during the winter and spring of 1866-67, and subject to a kind of distant blockade thereafter. Per the terms of an 1868 treaty, Ft. Kearny and the two other Bozeman posts were abandoned; they were then sacked and burned by the Indians.

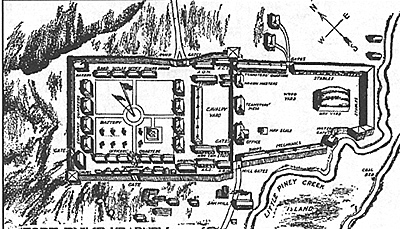

When I first visited the site of Ft. Kearny in 1976, there was nothing but a fieldstone marker on the dusty plain. Thanks, however, to a state-private partnership which finally reached critical mass about ten years ago, there exists today better directional signage from Route I-90, a five-percent reconstruction of the 1,400 foot, 8'-high log palisade. Interpretive and location markers to cover most of the rest of the fort, and a modest, air-conditioned Visitor's Center with bookstore. Historical archeology is a going concern at Fort Kearny: additional fieldwork occurs every year.

When I first visited the site of Ft. Kearny in 1976, there was nothing but a fieldstone marker on the dusty plain. Thanks, however, to a state-private partnership which finally reached critical mass about ten years ago, there exists today better directional signage from Route I-90, a five-percent reconstruction of the 1,400 foot, 8'-high log palisade. Interpretive and location markers to cover most of the rest of the fort, and a modest, air-conditioned Visitor's Center with bookstore. Historical archeology is a going concern at Fort Kearny: additional fieldwork occurs every year.

2. FETTERMAN BATTLEFIELD, WY (* * *)

Located only five miles from Fort Phil Kearny, this was the site of the so-called "Fetterman Massacre" of 21 December 1866. Glory-hunting Civil War veteran CPT (Brevet LTC) William J. Fetterman elbowed his way to the command of a mixed detachment of 81 cavalry and infantry bent on relieving a wood train under attack. A saucy Indian decoy party was led by the youthful Crazy Horse. Disregarding COL Carrington's explicit order, Fetterman chased the decoys north, over snow-studded Lodge Trail Ridge and out of sight of the fort, straight into ambush. The presence of some 2,000 Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors made for a battle lasting only about 30 minutes-but a battle it was. A looping, 1/2-mile trail laid out along the spine of Massacre Ridge, trail markers, and a fold-out interpretive map (all new since 1976) make plain the Army's attempts at tactical maneuver as the cavalry and infantry components, which had become separated during the pursuit, fell back under the cover of sharpshooters toward high ground, there to make an ultimately futile stand.

Those who reached the summit of the ridge tried firing volleys for awhile, as much to signal the fort as to intimidate the Indians: one man would shoot while another reloaded. Only toward the end did the situation descend into chaos. Once ammunition had been exhausted, every soldier was killed and mutilated. Fetterman himself was apparently among the last to go, huddling with his diminished command group behind a circle of their dead horses. Forensic evidence suggests that he and his old Army buddy, CPT Brown, probably finished each other off with simultaneous revolver shots to the temple.

In the aftermath of this fight, John "Portugee" Phillips wore out a horse by pushing it a record 236 miles in just four nights, to beg relief from the Army post at Ft. Laramie. Many aspects of the Fetterman battle-the most severe defeat the Army had suffered at the hands of Indians to that time resemble the larger-scale action at the Little Bighorn a decade later (with some of the same players on the Indian side).

The magnitude of the disaster only pointed up the tragic irony of a remark Fetterman had made in anger a couple of weeks earlier: "Why, with 80 men I could ride through the whole Sioux nation."

Access by car to the state-conserved part of the battlefield is easy; up-to-date interpretation corrects the many errors present in an original, turn-of-the-century stone monument. The surrounding terrain has changed relatively little since 1866, so that both the Indian and Army schemes of maneuver can be easily picked out from the summit of Massacre Ridge. A worthy, one-hour stop for the Ft. Kearny visitor.

3. WAGON BOX BATTLEFIELD, WY (***)

Located in a shallow, pine-fringed valley about five miles northwest of Ft. Kearny, this is where the Plains Indians first learned the power of the breach-loading Army infantry rifle. On 2 August 1867 a civilian woodcutting party, under attack by 800 Sioux, fell back to a little circle of 13 wagon boxes (Army wagons with the running gear removed) which the wood contractor had assembled for use as a makeshift stock corral. There, the contractors and their military escort--32 men in alk-held out for several hours until a relief force from Kearny scattered their opponents.

The 32 whites, their supplies, and dozens of horses and mules jammed into this improvised fortification, which measured only about six strides across by nine long, must have seemed a tempting prize to the Indians. The [after, under the guidance of Red Cloud and other chiefs gazing down on the scene from surrounding hills, executed at least three major charges, mounted and dismounted, from various directions throughout the day. While they had counted on coaxing one good volley out of the whites, then overrunning the wagon circle while the enemy paused to reload, the Indians were stunned by the Army's ability to keep up an apparently continuous fire. The soldiers were able to do this because they had recently been issued new Springfield breech-loading rifles. Two plainsmen packing Henry repeating rifles also punished the Indians severely. Three men were killed and two wounded on the Army side, while at least 60 Indians were killed and probably 100 wounded during the desperate struggle-some of which was fought at close quarters.

The circle of blue-and-red wagon boxes has been reconstructed in approximately its original location, surrounded by private land offering terrain more or less identical to that of 1867. Interpretative markers suffer somewhat from political correctness, but do add biographic and tactical detail of interest to the wargamer. If you are visiting Ft. Phil Kearny anyway, be sure to add this 20-minute stop.

4. BEAR BUTTE S. P., SID (**):

The slopes of this dramatic, isolated rock formation are sacred to a number of Plains tribes including the Cheyenne, Sioux, and Mandan. According to legend, this is where the Great Spirit gave the Cheyenne culture hero, Sweet Medicine, that tribe's four sacred Medicine Arrows and taught him the four Laws of Life--which in Cheyenne theology fulfill approximately the same role as do the Ten Commandments for Jews and Christians.

Indeed, a number of origins legends centering on the Butte seem to have been lifted directly from the Old Testament. For example, there is the belief that Bear Butte was the spot where a "great canoe" bearing a saving remnant of the Mandan people came to rest after the waters of the Great Flood began to recede.

While the tribes have a number of fanciful explanations as to how Bear Butte (Mato Paha) got its name, the most convincing is that from a distance of a few miles, its profile strongly resembles that of a sleeping bear. The Indians also call it Magic Mountain, and similar things. With the possible exception of Devil's Tower N.M. some miles to the west, Bear Butte is the most significant of all known Plains Indian spiritual sites. In 1857 and again in 1865, the northern Plains tribes gathered in vast conclaves at the foot of Bear Butte. At the later conclave, they concluded alliances in support of revenge raids following the Sand Creek Massacre, and decided on the main lines of Indian strategy for Red Cloud's subsequent war against the Bozeman Trail. George A. Custer's Yellowstone Survey Expedition of 1874 camped at the foot of Bear Butte, which then served as a kind of navigational beacon for the horde of gold prospectors and settlers who followed in Custer's wake.

Today there is a 1.7-mile-long hiking trail to the summit of Bear Butte, from which portions of four states can be seen on a clear day. Native Americans still travel here to establish sweat lodges and conduct personal vision quests-4raditional Indian offerings of tobacco wrapped in cloth can be seen tied to the limbs of trees by the side of the trail. The Visitor's Center shows a brief if dated orientation video, displays a number of interesting artifacts--4ncluding Red Cloud's own buckskin war shirt-and has a modest bookstore. Admission to the park is $3, on the honor system. A small herd of bison roams the flats below the butte.

5. FT. MEADE, SD (* * *):

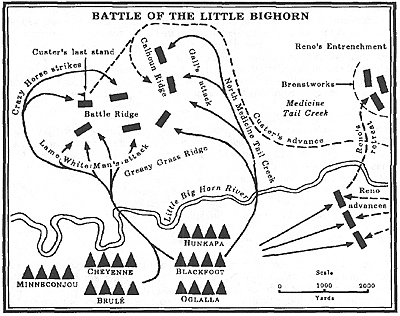

Ft. Meade-not to be confused with the charmless National Security Agency compound in Maryland bearing the same name-was established in 1878 about four miles from Bear Butte, to help break up any horde of troublemaking Indians who might wish to stage a final rally there. New home of the 7 th U.S. Cavalry Regiment (hastily reconstituted after its disaster at the Little Bighorn), the fort was on the main trail to the favorite Sioux hunting grounds, and near the confluence of three heavily traveled roads to the Deadwood gold fields. The power of the Plains tribes had already been broken for good by the time Ft. Meade was established, however, with the result that it never became a base for significant combat operations.

Over the years, a series of enlightened commanders developed this large (10company) post into one of the most beautiful and livable in the West. By the late 1880s Ft. Meade boasted brick-built officers'and senior NCOs'quarters, sidewalks, a bandstand, a theatre, lush green lawns, even gas street lighting! MAJ Marcus Reno, hard-luck senior survivor of the Little Big Horn debacle, was cashiered here in 1885 after his conviction on trumped-up charges of window peeping.

An intoxicated Reno allegedly ogled the comely teenage daughter of the 7th Cavalry's then- commanding officer, COL Samuel Sturgis, whose only son had died with Custer back in 1876. Ever since, the old man had openly blamed Reno for failing to bring his battalion to Custer's aid (and, by implication, save young Sturgis's life). The colonel's simmering personal vendetta meant that Reno, already half-broken in spirit, would get no slack from the ensuing courts-martial. stationed here until 1942, when the horses were sold off in favor of scout cars and light tanks.

The house wherein the alleged events occurred is still in perfect shape. The Fort was also tangentially connected with the adoption of "The Star Spangled Banner" as our national anthem.

From time to time, Ft. Meade was used as a test bed for a number of Army technical and organizational "improvements". At one time or another its tenants included mule-mounted infantry, an experimental bicycle-machinegun company, and a glider training school. During World War II it was used as a work camp for Afrika Korps POWs. The very last horse cavalry unit in U.S. Army history was

Though officially deactivated, Old Ft. Meade is still as neat as a pin. It is home to the most extensive and best-preserved collection of "Old Army style" Victorian architecture I have ever seen. Today, it hosts only a regional Veteran's Administration (VA) hospital and a summer training academy for South Dakota National Guard officer candidates. The Visitor's Center shows a 10-minute introductory film, contains extensive glass-cased exhibits of Old Army memorabilia, and offers a small but worthwhile bookstore. A nominal admission fee is charged. Using the Center's keyed map, drive yourself around the parade ground and soak in the fort's unparalleled, authentic atmosphere.

6. BIGHORN MEDICINE WHEEL, WY (**):

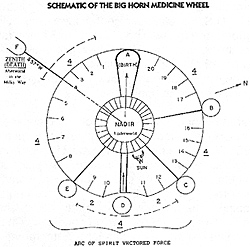

Several explanations exist for this impressive stone artifact, located on an isolated plateau high in the Bighorn Mountains of north-central Wyoming. The most cogent explanation I have seen states that the Wheel was built between 1,500 and 2,500 years ago by a group which later, having finished a slow migration southward from Canada, became the Chichimecs (Aztecs).

The Big Horn Medicine Wheel: The Birth and Death of Humanity by Jay Ellis Ransom (Cody, I Yellowstone Printing & Publishing, 1992).

According to this theory the Wheel had no astronomical or religious significance, but was instead a utilitarian construct. This was the spot at which the immortal souls of all Indians supposedly transitioned from their early lives underground, to live on Earth. It was also supposed to be both a place of pilgrimage for the restless spirits of the Indians' evil dead (i.e., poltergeists), and the means by which such evil spirits could be drawn upward to the afterlife, whence they could trouble the living no longer.

According to this theory the Wheel had no astronomical or religious significance, but was instead a utilitarian construct. This was the spot at which the immortal souls of all Indians supposedly transitioned from their early lives underground, to live on Earth. It was also supposed to be both a place of pilgrimage for the restless spirits of the Indians' evil dead (i.e., poltergeists), and the means by which such evil spirits could be drawn upward to the afterlife, whence they could trouble the living no longer.

In Uto-Aztecan cosmology the Great Spirit created new souls underground, forcing them to the surface as needed via a medicine structure such as the one in Wyoming. These liberated souls wandered the Earth until they could latch onto and inhabit a human fetus in its mother's womb. Years later, when the body a soul had inhabited finally died, the soul needed to return to the medicine structure to be directed upward, to the afterlife. Note the sharp contrast (in terms of directions, at least) with traditional Judeo-Christian conceptions regarding the path of souls: these speak of God sending souls down to Earth from the sky (Heaven), and evil souls descending from Earth to suffer lasting torment in an underworld (Hell).

To the ancients, the Wheel was thus a kind of doorway spirits used to travel in both directions-the place of both their "birth" (arrival) and "death" (departure) with respect to the Earthly plane of existence. The ancients went so far as to place huge stone arrowheads 60-100 miles away on the plains, pointing directly toward the Wheel, to help bad spirits navigate and get on with their exit journeys. There are obvious links between this site and at least two others: a much older partial wheel in Saskatchewan, Canada, and the misnamed Aztec Calendar Stone, which dates from about 1480.

Following the Conquest of Mexico, Catholic priests feared that the strange glyphs found everywhere on the Calendar Stone (itself 12 feet in diameter and weighing some 24 tons) contained cabalistic messages which could be used to support the perpetuation of an Aztec national cult. They therefore buried the Stone (in the foundations of a new cathedral in central Mexico City), and attempted to suppress all memory of its existence among the Indians. The Stone was only rediscovered in 1790. While it is in fact no calendar, the Stone does contain as its main element a stylized graphical version of the laydown of the Bighorn Medicine Wheel, surrounded and partially overlain by artistic motifs inherited from the Maya.

Today the Bighorn Medicine Wheel can be reached only after a 25-mile drive off Route 14, into the hills over unimproved roads, followed by a steep half-mile hike. I found it more convenient to view the video shown at the comfortable National Park Service (NIPS) regional visitor's center located about halfway between Sheridan and Cody, WY. The video is little more than a filmed version of the ranger walk offered at the site, anyway. NPS interpretation of the Wheel's significance is surprisingly muzzy, containing none of the above detail and content to disseminate the convenient theory that the site was some sort of Indian observatory. The role of the NPS at this site seemed to be merely that of security guard (the site had been vandalized in decades past, including by some would-be "interpreters"). NIPS personnel also serve as gatekeepers for the Native Americans who occasionally visit the Wheel to pray.

7. FT. CASPAR (PLATTE BRIDGE STATION), WY (***)

This little collection of log-walled huts was the scene of an attack by Indians raiding the Platte Valley Road in July 1865. The fort's main jobs were to maintain miles of telegraph line to the east and west, and to guard the 800-foot long bridge which an entrepreneur had constructed near the "Mormon Crossing" of the Platte River some years before. During the Indian attack, 1 LT Caspar Collinsn officer of Ohio volunteer troops and son of the regional military commander-was killed.

Young Collins spoke Lakota fluently, maintained friendships among the Indians, and was by all accounts a really nice guy. He was "just passing through" Platte Bridge Station enroute to another assignment when the call went out to escort an approaching train of supply wagons through a cloud of hostile Indians. Since no local officer cared to risk his life so close to his unit's promised demobilization date, Collins got the command by default. He sensed disaster so strongly that he gave away prized personal possessions before heading out the gate. In the ensuing armed clash, Sioux warriors recognized Collins and were disposed to spare him, but some Cheyenne who were also in the fight did not, and closed in. Had Collins not stopped to try to pull a wounded, dismounted trooper up onto his own horse, he almost certainly would have made it back to the fort alive.

The city of Casper (sic), WY was subsequently named for him. Today Ft. Caspar has a new but distinctly second-rate Visitor's Center, several buildings with reconstructed interiors and dioramas showing the material details of frontier military life, and an unexpectedly well-stocked, volunteer-run bookstore r puted to be one of the best in the West. Authenticity of the experience is only slightly compromised by the sandpit, modern house, and commercial buildings overlooking the site. Admission is free.

8. CRAZY HORSE MEMORIAL, WY (****):

In 1940, reservation Sioux invited a young, relatively unknown Boston-area sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski (pron. KOR zhak Tsol' KOV ski) to the Black Hills to undertake what would become the most ambitious sculpture project in world history. The intent of the project was to remind white people, whose government had just dedicated the four titanic faces on Mt. Rushmore, that the Indian race had its heroes, too. Korczak and his host, Chief Henry Standing Bear, picked out a southwest-facing, Indian-owned mountain ridge a few miles from Rushmore. This they would begin to reshape into a gigantic likeness of the martyred and unrepentant Indian war chief, Crazy Horse. Within days, Korczak had executed a dramatic 1:34-scale plaster model of his subject: a mounted Crazy Horse, pointing imperiously across the Black Hills toward the distant Rocky Mountains.

For an inscription, Korczak chose the answer Crazy Horse was said to have given to a smart aleck Eastern newspaper reporter. When the latter noticed the great warrior in shackles at Fort Robinson, NE, shortly before he was basely murdered, the Easterner sneered, "Tell me, chief, where are your lands now?" Crazy Horse replied instantly: "My lands are where my dead lie buried." Korczak himself is buried directly beneath his massive creation, in a mausoleum Frotected by huge bronze doors inscribed simply: "Korczak: Sculptor of This Mountain."

After WWII, having built himself a rough cabin and artist's studio on the lower slopes, the intrepid sculptor set to work on the mountain itself. He was alone. Decades of backbreaking toil and heavy indebtedness followed, but the work slowly progressed.

Superlatives naturally append themselves to such a gigantic undertaking. Crazy Horse's outstretched arm will be some 227' long; the entire sculpture 563' high. To date, something like 13 million cubic yards of granite has been removed from the mountain. Crazy Horse is being carved three-dimensionally, in the round: this fact alone sets the work apart from the Mt. Rushmore busts, not to mention the figures in the Confederate monument at Stone Mountain, GA, which are mere bas-reliefs. The scale of the Crazy Horse sculpture is such that all four of the heads on Mount Rushmore could fit inside Crazy Horse's head, which is 87.5 feet tall. The war feather crowning that head will itself be 44 feet high. The volume of the finished sculpture will be far greater than that of the Great Pyramid of Cheops and, being made of hard white granite, should last at least as long.

Korczak married and eventually fathered 10 children (several of whom, as adults, now labor on the mountain). When he died in 1982 the family-run, nonprofit foundation he had set up to administer the project was thrown into crisis--which it weathered with a renewed determination not to let the sculptor's life's work lapse. Bigger donations, better weather (thanks, global warning!), and advances in technology have meant faster progress on the giant sculpture: Crazy Horse's face was completed and dedicated on 3 June 1998. The remainder of the piece has also been roughed into shape, such that Crazy Horse is now recognizable from the main road at a distance of perhaps five miles.

Today a sprawling, modern visitor's complex is located a mile below the mountain. It is host to a museum of Plains Indian Ethnography and Manual Arts, displays on the technology and techniques associated with mountain carving, and one of the most complete and highest-quality Western bookstores/art galleries I have ever seen. Korczak's studio, in which he created bronzes and other works (by no means all of them Western-themed) when winter weather forced a suspension of his mountain carving, is worth a look. A highlight is the outstanding 20-minute orientation film which follows Korczak from his earliest, frustration-filled days on the mountain, through what might be called the institutionalization of the project after about 1970. Because neither Korczak nor the Sioux trusted the U.S. Government to support their effort to its conclusion (budget cuts had forced Gustav Borglum, whom Korczak greatly admired, to "declare victory" and abandon Rushmore before completing all he had planned to do there), not a penny of state or federal money has ever gone into the Crazy Horse Memorial. The Korczak Foundation survives on money donated by private charitable trusts, major corporations (though this is handled so discreetly you would hardly know it), and the visiting public, plus grants-in-kind from explosives makers, mining concerns, trucking companies, heavy-equipment rental firms, and the like.

While it doesn't have much to contribute to Indian Wars gaming per se, a visit to the Crazy Horse Memorial is nevertheless a potentially life-changing experience. I thought I might drop by for an hour, but ended up staying half a day. If your kid has problems with focus and direction, sustaining his motivation, perspective, etc., forget Ritalin. Forget military school. Bring him here. The single-minded determination and sheer guts of the otherwise cultivated and urbane Korczak Ziolkowski can only serve as an inspirational object lesson to slackers everywhere. Above all, he was a man dedicated to a worthy dream he knew he could never live long enough to see realized, but behind which he established considerable momentum by sheer force of will.

While it doesn't have much to contribute to Indian Wars gaming per se, a visit to the Crazy Horse Memorial is nevertheless a potentially life-changing experience. I thought I might drop by for an hour, but ended up staying half a day. If your kid has problems with focus and direction, sustaining his motivation, perspective, etc., forget Ritalin. Forget military school. Bring him here. The single-minded determination and sheer guts of the otherwise cultivated and urbane Korczak Ziolkowski can only serve as an inspirational object lesson to slackers everywhere. Above all, he was a man dedicated to a worthy dream he knew he could never live long enough to see realized, but behind which he established considerable momentum by sheer force of will.

If you find yourself anywhere in the region, this site is not to be missed-as much for what it teaches us about the human spirit (Crazy Horse's, and his sculptor's), as for the particulars of the carving. Just the thought that the Crazy Horse sculpture is expected to be around to ring in one, two, even three or more new millennia boggles the mind. Anyone who doubts that in America a single person really can accomplish just about anything, need only look to the Memorial for proof. Adult admission is $8.

Back to MWAN #116 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com