Series Overview:

Almost everyone with an interest in the Wild West has heard of such legendary "wideopen towns" as Abilene, Virginia City, and Deadwood. This article is the second in an occasional series on the forgotten "bad neighborhoods" of the American frontier - places just right to use as settings for an Old West skirmish scenario or short campaign. The first article in this series, on Canyon Diablo, Arizona, appeared in MWAN #105 and 106.

The brief but violent heydays of the towns I describe in this series offer the history-minded miniatures gamer a great deal of grist for scenario building. Below you will find game-relevant information on the history, economy, and populace of Beer City and the region surrounding it.

Together it is enough to create an integrated and historically accurate venue for Wild West gaming at the skirmish level. Compress the history a bit, drawing on the elements you like to construct scenarios that, while they provide wilder single days than occurred even in Beer City, will at least have as their foundation the real life of a once-real town.

The Setting: "No Man's Land"

The Setting: "No Man's Land"

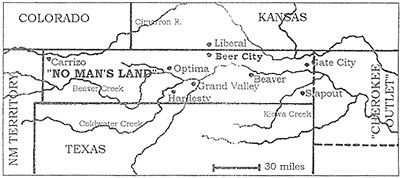

Beer City owed its very existence to a geographic absurdity - a glaring mistake on the part of,both cartographers and politicians called No Man's Land. This land had once been, at least officially, part of the Mexican province of Texas. The United States annexed the Texas Territory in 1845. At that time a long, narrow strip of land (170 miles long by 34 miles wide) was removed from north Texas to comply with their Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had dictated the northernmost limit to which slavery could be extended by the addition of new states. While this adjustment officially fixed the northern boundary of Texas at 36-0-30 latitude, the southern frontier of Kansas and Colorado had already been set at 37-0-0. In between lay No Man's Land, its 5,780 square miles assigned to absolutely no one. The eastern and western borders of No Man's Land were the edge of the so-called Cherokee Outlet at the 100th meridian, and the border of New Mexico Territory, respectively (see illustration). Congress eventually began to call the resulting, orphaned region the Public Land Strip. It was the New York Sun that gave the anomaly its catchier moniker, in an editorial that referred to it as "...God's land, but no man's."

The passage of time did not help much to clear up confusion over the region's status. As late as 1885 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that No Man's Land was not, in fact, part of the Cherokee Outlet to the east, as many locals had believed. The Interior Department merely offered the opinion that the area was "...in the public domain", and thus open for anyone to settle.

The first white men to traverse the Public Land Strip regularly were cattlemen, driving their herds north from Texas to the great railheads in eastern Kansas. A man named Lane even opened a "road ranch" (guest house-saloon) near the later site of Carrizo (modern-day Kenton, OK). More substantial settlement had to wait until the end of the Civil War. As a result of the Homestead Act of 1862, some local surveying had already been done and a number of spurious "townships" laid out.

By about 1880, No Man's Land supported--though very meanly--some 12,000 sodbusters, small merchants, casual laborers, and other residents, including a shockingly high proportion of out-and-out miscreants. Since wood was scarce on the plains, most folks lived in houses with sun-baked sod walls 18"-24" thick. A 12"-thick roof of sod was laid across closely-set timber rafters and a mat of green rushes.

Living in a "soddy" was rather like living in a cave, but without all the amenities. The soddy's one or two windows were usually covered by wooden shutters, since glass had to be "imported" from back East and was therefore expensive. There was only an inefficient smoke hole in the roof to ventilate the interior----itself only indifferently warmed by a noxious, dung-fueled fire. While the infiltration of rainwater and/or groundwater were mostly problems confined to the spring and fall, worms and insects were likely to emerge from the soddy's ceiling and interior walls all year 'round.

Living in a "soddy" was rather like living in a cave, but without all the amenities. The soddy's one or two windows were usually covered by wooden shutters, since glass had to be "imported" from back East and was therefore expensive. There was only an inefficient smoke hole in the roof to ventilate the interior----itself only indifferently warmed by a noxious, dung-fueled fire. While the infiltration of rainwater and/or groundwater were mostly problems confined to the spring and fall, worms and insects were likely to emerge from the soddy's ceiling and interior walls all year 'round.

Three or more soddies clustered together at a wide spot in the road qualified as a settlement; land speculators made sure that even groups of eight or ten such huts were glorified on maps as 'towns" or "cities." Each habitation had at least one saloon (or general store, where one could also buy a drink). The sole exception was the flyblown little village of Slapout, named for the habitual response of the store's proprietor to requests for any kind of merchandise: "Sorry, we're slap out of that." Gate City had two stores, a blacksmith's shop, and a post office. Neutral City substituted saloons for the last two; so did Hardesty. Carrizo amounted to three saloons and an open-air lunch counter. Optima, Grand Valley, and Paladora. each consisted of a post office and a soddy or two. Still, they were better off than the would-be village of Nevada, which remained confined to a set of surveyor's stakes.

Next to these, an unsavory place called Old Sod Town practically ranked as a metropolis: it boasted a dozen sod buildings. In the mid-1880s, Old Sod Town was a center not only for moonshining (residents peddled rotgut whiskey-illegally-to Indians living across the border in the Cherokee Outlet), but horse-stealing as well. The Chitwood Gang monopolized the latter trade, until vigilantes killed one of the gang's members and ran the rest off.

Indeed, moonshining was one of the three dubious pillars of No Man's Land's economy.

There were several large-scale distilleries in No Man's Land. One was run out of a hidden cave near Gate City; another could be counted on to deliver two barrels of "good" whiskey (and several more of rotgut) per week.

The other two pillars were: 1) the reclamation of tons of buffalo and cattle bones that lay scattered across the plains (an early form of recycling).

Buffalo carcasses, relics of the great hunts of the early 1870s, lay as thick as 50 per acre in places even ten years afterward. Scattered among them were the skeletons of thousands of beef cattle, victims of the Great Blizzard of 1886. A ton of bones brought $8-10 in Dodge City, Kansas, while horns suitable for making into knife handles brought even more. And 2) the now-vanished profession of "road-trotting". This was practiced by con men who filed specious claims to other people's land, in hopes of being paid to withdraw the claims later.

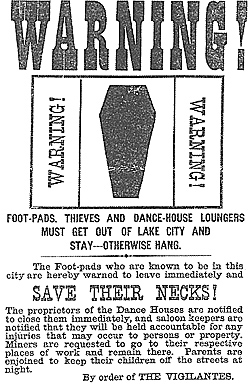

You might imagine that, in such a hardscrabble environment, the rule of law would be weak and popular concepts of justice pretty rough. And you'd be right: a spirit of self-reliance, frequently shading into vigilantism, ruled No Man's Land. Due to the peculiar circumstances under which the region was founded, there was no basis whatever upon which to either pass or enforce laws. Since it was demonstrably not a U.S. state, territory, commonwealth, possession, or the District of Columbia, Federal law simply did not apply in No Man's Land. The U.S. marshals who occasionally passed through the region were utterly without authority. There were no local law enforcement structures, either: the only recognized officials in No Man's Land were the mayors elected by each of the larger settlements. Criminals simply went unpunished unless a group of aggrieved citizens banded together to stop them.

The criminal element seems to have recognized more or less instantly the immunity afforded them by No Man's Land's special status. Indeed, the highest-profile misdeeds that originated in No Man's Land had as their targets the people and property of neighboring states. "Black Jack" Ketchum, for example, held up the railroad over in New Mexico Territory three times; after each job, he fled to Tug Toland's ranch deep in No Man's Land. When the conductor badly maimed Ketchum's arm with a load of buckshot during the third heist, however, the bandit was caught and tried in New Mexico.

Ketchum was convicted and sentenced to be hanged at dawn. Facing the crowd, he shouted, "I'll be in Hell before you start breakfast, boys! Let 'er rip!" The hangman was either inexperienced or especially vindictive, however, because the resulting drop tore Ketchum's head off.

As was perhaps to be expected from such a tough crowd, the citizens of No Man's Land took care of themselves pretty effectively. When a drunk began shooting up the town of Beaver, for example, the locals simply killed him and buried him in an unmarked grave. A man named Broadhurst gunned down a neighbor who had allegedly insulted Broadhurst's wife. When the residents of one village took issue with a certain saloon owner's business practices, he began taking potshots at the sod hovels owned by his opposition: but a storm of return fire cut him down.

As was perhaps to be expected from such a tough crowd, the citizens of No Man's Land took care of themselves pretty effectively. When a drunk began shooting up the town of Beaver, for example, the locals simply killed him and buried him in an unmarked grave. A man named Broadhurst gunned down a neighbor who had allegedly insulted Broadhurst's wife. When the residents of one village took issue with a certain saloon owner's business practices, he began taking potshots at the sod hovels owned by his opposition: but a storm of return fire cut him down.

Said one veteran of No Man's Land, "There were no dockets, no long trials, no court expenses, no appeals, no paroles, and no pardons." One of the few manifestations of collective authority eventually appeared in an entity called the Respective Claims Board, which some leading citizens established to extinguish bogus claims to land and thus rid No Man's Land of the "road-trotter" nuisance. Even then, the Board enforced its decisions at the point of a gun.

In time, vigilantes either killed most of the worst offenders in No Man's Land, or forced them to flee. They even hanged one pair who let it slip that they were merely plotting to rob the big distillery near Gate City.

Beer City: "The Sodom and Gomorrah of the Plains"

By the mid- 1880s, the often violent anti-saloon crusade led by Carry Nation had "dried out" Kansas to such an extent that the nearest place for many Kansans to get a legal drink was No Man's Land. The Rock Island Railroad reached Liberal, Kansas in Spring 1888, turning that former backwater into a major regional railhead almost overnight. A new habitation promptly sprang up just across the border, in No Man's Land, to accommodate the needs--both for alcohol and for feminine companionship of Liberals, cowboys, stockmen, and railroad workers. At first christened White City because it was roofed mostly with tents, it soon came to be known as Beer City in honor of its main industry.

There was, indeed, nothing much in Beer City but saloons and dance halls. It had no church, no school, not even a post office. During the spring months when cattle drives were ending, waves of prostitutes from Dodge City and Wichita converged on Beer City to ply their trade. Even more commuted over from Liberal, arriving on the daily stage. Prominent saloons included the Elephant and the Yellow Snake; the house of ill fame above the latter establishment was run by one Pussycat Nell.

In another example of frontier justice, Nell was not arrested when she killed a visiting lawman and sometime rustler, Lew Bush, with her shotgun. The cause of their dispute is not recorded.

In the high season, Beer City came very close to being a round-the-clock party town. Dances were held frequently; people came from as far as 50 miles away to attend them. Such affairs stayed orderly in part because the only person allowed to carry a gun was the cloakroom attendant. The town fathers actually advertised Beer City as "...the only place in the world where there is absolutely no law."

They staged horse races, boxing and wrestling matches, gaudy Wild West shows, and other spectacles to keep visitors interested between drinks. Some saloons furnished "drunk pens'!--highwalled enclosures topped with barbed wire in which an inebriated cowboy could take refuge in an effort to avoid being rolled for his last nickel. An Eastern reporter's description of the town of Beaver could easily have been applied to Beer City as well: "...If [the population] 'floated', it was on a sea of alcohol. If they sailed or flew, the breeze that wafted them onward was heavy with the fumes of tobacco and the smoke of gunpowder. If they drifted, they were stranded at the shortest intervals on bars not made of sand.'

Decline and Fall

The high-water mark for No Man's Land came when local boosters formed a self-described "provisional government" and petitioned Washington for territorial status. They sent representatives East to lobby key Congressmen, in a vain attempt to convince them that No Man's Land, once it had been renamed "Cimarron Territory", would be both an economically viable and socially respectable part of the Union.

But the end was near. Wheat prices were not high enough to make a real go of farming in the putative Territory, and for most people existence remained hand-to-mouth. The summer of 1888 brought a severe drought, crushing the hopes of even the best-situated sodbusters. One family recalled planting 50 acres of corn, which yielded ears enough only to make a single meal. Shortages of corn, too, finally began to dry up the moonshining business. Finally, by that time the supply of beef and buffalo bones on the prairie was almost exhausted, along with the supply of desiccated animal dung--the staple fuel. One citizen lamented in verse:

- Pickin'up bones to keep from starving,

Pickin'up chips to keep from freezing,

Pickin'up courage to keep from leaving,

Away out yonder in No Man's Land.

The provisional government folded. The surfeit of criminals drifted away; few people had much cash, and crime no longer paid as well as it once had. When settlers from the East rushed into Oklahoma beginning on 22 April 1889, many in No Man's Land came in from the opposite direction to join them. The little region's population dropped from perhaps 9,000 to under 2,500 within a couple of months.

Epilogue

The Oklahoma Organic Act of 1890 made the Public Land Strip part of the new Oklahoma Territory. The three massive land grants the King of Spain had originally made in the area became the modern-day counties of Cimarron, Beaver, and Texas (collectively known as the Oklahoma Panhandle). Things began to look up almost at once: more (and better) people moved in, including a number of blacks who took part in schemes to "colonize" Oklahoma as a means of escaping the Jim Crow South. Real law came to the strip for the first time. Locally elected sheriffs, tough federal judges, and deputy U.S. marshals (one of them the widely-feared Chris Madsen) soon 'civilized" the former No Man's Land. Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907.

Beer City as a Setting for Skirmish Wargaming

One could set a skirmish-level miniatures campaign in Beer City depicting the events circa April-June 1888, when the territorial delegation was still in Washington, yet before the drought arrived in full force. Such a campaign might in many ways resemble the Prohibition Wars of the 1920s, with rival factions battling for control of the lucrative saloon trade, moonshining, prostitution, and gambling rackets. No submachine guns are available, alas, but the array of colorful characters in No Man's Land more than makes up this deficiency.

Off-season, Beer City's "customers" were thirsty Kansas males, among them a sprinkling of African-Americans. The "host" population was composed of that mix of Irish, black, and assimilated barmen, hookers, marginal merchants, draymen, and itinerant swindlers that enlivened many Western towns. There would be no Army or Mexican presence, and few Indians except of the most demoralized kind. At the end of a cattle drive (April-May 1888), however, there would be plenty of rambunctious cowboys of all stripes about.

One can imagine a scenario set in "downtown" Beer City when the cowpokes hit town one afternoon: fatal gunplay over the rackets breaks out to rival the other "entertainments" going on all around (bare-knuckle boxing, a cockfight, a sharpshooting exhibition, the scripted "rampage" of Wild West Show Indians--real or bogus--down Main Street)...

If you liked this article, see also Painted Sunset (Stenhouse Game Productions, 1998: http://www.stenhousegames.co the author's booklet of historical miniiatures scenarios of Army-Indian conflict in the Old West.

Back to MWAN #111 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com