Okay Gamers! As promised in my last column (MWAN 100), this article concludes my discussion of solo campaigning and features the campaign of the Texas Revolution. You may want to review that piece in conjunction with this one. Let me remind you readers that the solo techniques I am describing can be used, with very little modification, to run group campaigns, particularly if one fellow agrees to play the role of game master. Now without further ado, I present...

The Texas Revolution Campaign Game

Concept. In this game, I am going to control both sides (and show no favoritism). Typically a solo player controls one side and uses various techniques to control the maneuver of the other side. However, in this particular campaign, I wanted to use logistics (which actually drives the Mexican and Texan strategies for reasons which will become apparent) and this meant a fair amount of book keeping. Certainly I could have asked some assistant (smart child, significant other etc.) to adjust the numbers each turn to reflect combat losses/reinforcements and food consumption but this would become inconvenient considering the frequency of turns.

Time is handled by fifty-two weekly turns. A turn includes the following phases:

- Mexican movement

- Combat resolution

- Texan movement

- Combat resolution

- Generate food

- Consume food

- Add reinforcements if appropriate

I designed a simple table to track turns and to remind me when reinforcements were due to show up on the map.

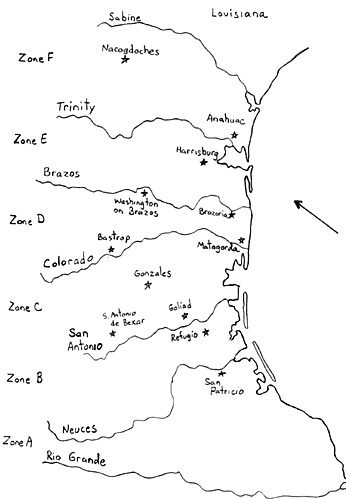

Space is limited to the populated areas of the province of Texas. Therefore, game play goes no farther west and north than an imaginary line drawn about 150 miles inland of the Gulf of Mexico. The southern limit is the Rio Grande and the eastern limit is the Sabine River, the border with Louisiana. While I use a hex map to control movement, the map shown here is without hexes to better illustrate the towns and rivers. I put the map on a styrofoam sheet and used colored and numbered pins to represent troop units.

My map shows no roads. Movement rates are uniform across the flat terrain and there was no penalty for crossing those piddly streams that Texans refer to as rivers. Pure cavalry forces travel 50% faster than other forces (6 vice 4 hexes per turn in my game).

Goals are measured by control of towns as well as the land between the major rivers. These areas I have called zones.

| Zone | Area | Included Towns |

|---|---|---|

| A | Land between Rio Grande and the Neuces | San Patricio |

| B | Between the Neuces and the San Antonio | Refugio |

| C | Between the San Antonio and the Colorado | San Antonio, Goliad, Gonzales, Matagorda |

| D | Between the Colorado and the Brazos | Washington-on-Brazos, Brazoria, Bastrop |

| E | Between the Brazos and Rio Trinidad | Harrisburg |

| F | Between the Trinidad and the Sabine | Anahuac, Nacogdoches |

In the goals established below, a zone is occupied when a Mexican force of any size is in each town in the zone and no Texan force greater than 100 men is also in the zone.

Total Mexican victory Zones A through F occupied, no Texan forces remaining.

Substantial Mexican victory Zones A through D occupied.

Marginal Mexican victory Zones A through C occupied.

Marginal Texan victory Mexicans occupy no more than Zones A through C.

Substantial Texan victory Mexicans occupy no more than Zones A and B.

Total Texan victory No more than Zone A occupied by Mexican forces.

If the Mexican player achieves the conditions of a total victory at any time in the campaign, he is declared winner. Otherwise, the game goes for 52 turns and the conditions in existence after the 52nd turn determine victory.

Logistics

In this game I only played two aspects of logistics - units of food and reinforcements of soldiers. For food, I decided that I would consider soldiers only, not their mounts. I also assumed that civilians could feed themselves and therefore didn't fall into my calculations. I just based my food requirements on the number of soldiers. I also assumed away a requirement for wagons and teams. I figured that any force could carry food with it without restriction (for example, beef on the hoof). Yes, this is simplistic but it keeps the play less complicated. Then I defined a unit of food as enough to feed 100 soldiers for 1 week (i.e. one turn). At the end of each turn I just subtracted I food unit for every 100 soldiers. For ease of book keeping, I rounded the numbers. For example, if a unit had 365 troops, it consumed 4 food units each week. But a unit of 145 consumed only one and any unit 50 or less consumed no food at all! If a unit runs out of food, it loses 25% of its men each turn. This reflects a loss of strength to desertion or to troops being sent out to forage. In any event, troops lost never rejoin the unit.

I also allocated a food potential for the town (see the section on towns below). For example, I figured that San Antonio and the surrounding ranchos could generate 10 food units each week. Thus, whoever occupies San Antonio at the end of a turn adds these food units to any troop units in the zone or to his stockage in that town. Troops departing a town can carry food units with them. Of course, if the occupying force is 2000 soldiers, then 20 units of food are consumed. Now, this means that I have to track food units for each town and for each force and account for consumption (troops) and food generation (towns) each turn. Again, I am not playing logistics because it is fun, but rather because it drives strategy.

I discuss troop reinforcements in the sections below on the Mexican and Texan forces. Basically, the Mexicans get a battalion of 400 troops and a battery of 4 guns every four turns. The Texans get 25 recruits appearing in the towns under their control every four weeks as well as volunteers from the United States.

Towns

Towns are important for two reasons. First, the victory conditions are defined in terms of control of towns as well as eliminating Texan forces in the various zones. Texans garrisoned and fortified areas in each town so that they could withstand siege by larger numbers of Mexicans. Second, it is the towns which provide food and Texan recruits. The side which occupies the town gets the food and if the Mexican player is the occupational force, the Texans are deprived of the additional recruits.

So, for each town I designated a recruit and a food generation capability. For ease of record keeping, each town started with 10 food units and produced 10 food units each week and 2 5 recruits every four weeks. I recorded the current amount of food units on hand in each town on a table. Data was penciled in so that it could be changed as the situation warranted.

Town Current food total (food units)

San Patricio

Refugio

San Antonio

Goliad

Gonzales

Bastrop

Matagorda

Brazoria

Washington-on-Brazos

Harrisburg

Anahuac

Nacogdoches

Mexican Forces

Mexican forces came in three varieties. Permanentes were the regular forces. This included the elite Zapadores battalion. Presidiales were garrison troops but were very experienced Indian fighters and consequently fine soldiers. Activos were the state troops, raised as necessary to suppress rebellion and therefore nearly the equal of the permanentes. However, as much as 20% of this force was made up of new recruits. While the troop list below is historically accurate, I chose a non-historical brigade organization to give me more maneuver elements. Each brigade is represented by a pin on the campaign map. I grouped the Mexican forces as follows:

1stInfantry Brigade: Aldama Permanente Infantry Battalion (400) Guerrero Permanente Infantry Battalion (400) Tres Villas Activo Infantry Battalion (200, all green recruits) 4 guns total: 1000 troops

2nd Infantry Brigade: Jimenez Pennanente Infantry Battalion (270) Matamoros Permanente Infantry Battalion (270) Guadalajara Activo Infantry Battalion (420) 4 guns total: 960 troops

3rd Infantry Brigade: Queretaro Activo Infantry Battalion (370) Is' Toluca Activo Infantry Battalion (320) Yucatan Activo Infantry Battalion (300) 4 guns total: 990 troops

4th Infantry Brigade: Guajanuato Activo Infantry Battalion (400) San Luis Potosi Activo Infantry Battalion (450) 4 guns total: 950 troops

5th Infantry Brigade Morelos Permanente Infantry Battalion (300) Zapadores Battalion (200) 1st Mexico Activo Infantry Battalion (350) 4 guns total: 850 troops

1st Cavalry Brigade: Dolores PeTmanente Cavalry Regiment (290) Rio Grande Presidiale Company (60) Total: 350 cavalry

2nd Cavalry Brigade: Tampico Permanente Cavalry Regiment (250) San Luis Potosi Auxiliary Cavalry Troop (40) Bajio Auxiliary Cavalry Troop (30) Total: 320 cavalry

3rd Cavalry Brigade: Cuautla Permanente Cavalry Regiment (180) Guanajuato Activo Cavalry Regiment (180) Total: 360 cavalry

Each Mexican unit starts the game with enough food units to last 6 weeks. Thus the Mexicans have to be fairly aggressive in capturing towns since they consume 58 food units every week!

Mexican replacements arrive on the Rio Grande as a battalion of infantry (400 soldiers) and a battery of four guns every 8 turns.

Texan Forces

The government of Texas authorized a bewildering array of types of forces from regulars to militia. Except for the several hundred deserters from the U.S. Army in Louisiana, most probably had little if any training in drill. Therefore, I chose to represent all my Texans uniformly and without distinctions. On the first week of January, 1836 (turn 1) I set out a force structure of 2000 infantry and 100 mounted rifles.

These forces start out in the twelve Texan towns. I figured that a small number of Texans would remain in each town as a garrison while some other number would be moved about the map and presumably toward larger towns or against a Mexican column. I wanted some guns to remain with the garrison. These guns were not field guns which could accompany the maneuver force but guns which because of any number of reasons (no limbers, insufficient horses etc.) had to be left in the towns. There would be a smaller number of field guns which would accompany the maneuver forces.

Therefore, I put two pins in each of the twelve Texan towns - one representing the garrison and one the maneuver force. An example of the breakdown appears below.

| Zone | Town | Garrison/guns | Maneuver Force/field guns |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | San Patricio | 25/2 light guns | 150 |

| B | Refugio | 50/1 light gun | 100 |

| C | San Antonio | 50/4 light, 4 medium, and 2 heavy guns | 150 and 2 light field guns |

| C | Goliad | 50/2 light and 2 medium guns | 100 plus 100 mounted rifles and 2 light field guns |

| C | Gonzales | 50/no guns | 100 |

| D | Bastrop | 25/no guns | 100 |

| D | Matagorda | 25/2 light guns | 150 |

| D | Brazoria | 50/2 light guns | 200 and 2 light field guns |

| D | Washington-on-Brazos | 50/2 light and 2 medium guns | 150 |

| E | Harrisburg | 25/no guns | 100 |

| F | Anahuac | 25/2 light guns | 100 |

| F | Nacogdoches | 25/4 light and 4 medium guns | 150 |

| Total | 450/35 guns | 1550 and 6 field guns | |

Man for man, the Texans fight better than the Mexicans (or else the game is horribly one- sided). I attribute this to a greater proportion of rifles in their units and the fact that they are all volunteers rather than drafted peons far from home.

Texan replacements. The Texan Army raises new forces from two sources. First, each town under Texan control generates 25 recruits every four weeks. I can add these forces immediately to any Texan force in that zone or leave them to bolster the garrison of any town (except one currently under siege).

The second source of Texan replacements is volunteers from the U.S. The numbers of volunteers increase as time passes. For example, 100 volunteers each month until May, 150 per month from May through August, and 200 per month between September and December. This acceleration of Texan volunteers encourages Santa Anna to move as quickly as possible to defeat the Texans. The Texans also get two light guns donated by friends in the U.S. every four turns. The volunteers from the U.S. and the guns arrive at Brazoria on the Brazos River. If Brazoria is occupied, they arrive at Anahuac or other northerly city unoccupied by Mexicans. I represent these forces as a new pin until such time as I link them up to an existing maneuver force or attach them to a garrison.

Unit Cards

Each group of forces is represented by a pin on the map as well as a note card with bits of information penciled in. A sample unit card for a Mexican force appears below.

| 1st Infantry Brigade (pin 1) | Troops: | Guns: 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Aldama Permanente Infantry Battalion | 400 | |

| Guerrero Permanente Infantry Battalion | 400 | Food Units: 60 |

| Tres Villas Activo Infantry Battalion | 200, all recruits | |

| - | Total: 1000 | - |

At the end of each turn, I adjust the numbers to reflect losses, replacements, and food consumption or resupply of food units.

Play of the Game

When a Mexican pin and a Texan pin find themselves in the same hex, some resolution is required. You have the choice of setting up each engagement and siege on the wargame table or using board game techniques to resolve the situation. Each soloist has his own favorite wargame rules so I'll just note a few possibilities for resolution.

Very often one force will be significantly smaller than another and would logically refuse combat. If I decide to refuse combat and if the unit has an adjacent hex unoccupied by the enemy, a unit can decide to take a loss and move to the open hex. Just subtract 10% or 25 troops (whichever is larger) from the troop strength. If all adjacent hexes are occupied by the enemy, fight out the current action or pay the penalty, move into an adjacent hex and fight that enemy. For all you board gamers, I don't recognize "zones of control". However, you can't move through a hex occupied by the enemy without resolving the issue as described above.

When I want to conduct the fight on paper rather than on the table, I count up troop strength, figure out the ratio, and consult the tables below. Guns count for 25 troops.

Use this table when the larger side is less than twice as large as the smaller side.

Roll: Result

1: Both sides lose 20% of their respective strengths; larger side withdraws to adjacent hex.

2: Smaller side loses 20%; larger side loses 15%; larger side withdraws to adjacent hex.

3: Smaller side loses 20%; larger side loses 10%; larger side withdraws to adjacent hex.

4: Smaller side loses 20%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

5: Smaller side loses 40%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

6: Smaller side loses 50%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

Use this table when the larger side is twice as large as the smaller side or larger.

Roll: Result

1: Smaller side loses 20%; larger side loses 10%; larger side withdraws to adjacent hex.

2: Smaller side loses 30%; larger side loses 10%; larger side withdraws to aqj acent hex.

3: Smaller side loses 30%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

4: Smaller side loses 40%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

5: Smaller side loses 50%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

6: Smaller side loses 75%; larger side loses 10%; smaller side withdraws to adjacent hex.

Sieges are frequent. Fight them out on the table if you want. I use the following. If the besiegers are less than 4 times as strong, a stalemate exists. The defender can't withdraw and both sides consume food at the usual rate and pay the usual penalties when they run out of food. However if the besieger has greater than 4 to I strength, then I use the table below during the besieger's combat resolution phase.

Roll: Result

1: Defender losses 10% of strength. Besieger loses twice that number. Siege continues.

2: Defender losses 15% of strength. Besieger loses twice that number. Siege continues.

3: Defender losses 20% of strength. Besieger loses twice that number. Siege continues.

4: Besieger assaults. Fails. Both sides lose 20% of their strength. Siege continues.

5: Besieger assaults. Wins. Besieger loses 20% strength. Defender wiped out.

6: Besieger assaults. Wins. Besieger loses 10% strength. Defender wiped out.

This sets up an interesting case when a siege is going on and a relief force shows up! I always play those out on the table.

As the Mexicans move deeper into Texas, they must leave a garrison in the towns they capture. I require them to leave at least a battalion of 200 or more troops. This drains away Mexican strength and helps balance the game. There is no requirement that Texans physically occupy a town; they are free to abandon a town if they choose. I've never done this. I keep the Texans in the towns, even when vastly outnumbered, to tie down a column of Mexicans.

I also identify which force Santa Anna is traveling with. If the Texans can defeat that column, I give them a 1 in 3 chance of capturing that general and ending the conflict immediately with a Texan victory! This dynamic persuades me, when I'm in the Texan phase, to mass whatever forces I can and try to bring Santa Anna's column to a fight. Of course, the Mexicans are moving in three or four columns to challenge as many towns as quickly as possible. I keep the cavalry brigades between the columns to move around and cut off any isolated Texan forces.

Summary

There you have it, a short version of how a soloist can conduct a campaign on a map and wargame table. As a soloist, I can tinker with the rules at my leisure to get the right balance or I can try to replicate the historical context which very often favors one side over the other. I for one am astounded that Sam Houston and the Texans pulled it off. They had very little going for them; particularly after the initial catastrophic defeats at Goliad and the Alamo.

Remember, these suggested rules with some modification are usable for group gainers with or without the use of a gamemaster. I would be very interested to hearing from a group who tried these suggestions to drive a campaign.

Back to MWAN #102 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com