MWAN hits the century mark! Congratulations are in order for Hal, his writers, advertisers, and all those who helped and encouraged Hal through the years. I still remember with great fondness the day (a long time ago) when a wargaming buddy of mine, Milt Koger, introduced me to MWAN. I subscribed immediately and have enjoyed poring over its eclectic selections ever since. Even today, my biological alarm clock sounds when two months have elapsed since the last MWAN arrived in the mail. And I must add that writing this column provides an enjoyable release for intellectual energy. Hal, your contribution to the hobby has been immense and is immensely appreciated!

This column addresses one of the areas in which solo wargaming has a lot to offer the group gamer – Campaign Wargaming. Most group gamers only dream of participating in a campaign game but the soloist can wallow in campaigning to his heart's delight. However, it is clear that the methods used by the solo gamer are transferable to the group gamer. Before we address how the soloist sets up his campaign, let's review some of the issues, starting with definitions.

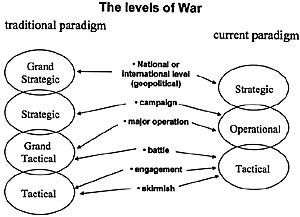

In military theory, one can talk about levels of war. The schematic shows two ways of looking at levels of war.

Even in an academic environment, people will disagree on what a campaign is or how it fits into a hierarchy of terms. I have shown two possibilities, one traditional and one in current use. To get a sense of what these terms mean, let's look at examples from Waterloo and World War II.

| Type | Waterloo | World War II |

|---|---|---|

| Geopolitical | Napoleon's desire to destroy each allied army in turn until the coalition against him collapses | Allied decision to defeat Germany first |

| Campaign (A campaign is a sequence of major operations and battles) | Napoleon's Army of the North moves on Brussels with the purpose of destroying two armies of the coalition | U.S., British, Canadians and others defeat Germany by landing in northern France and moving on Berlin |

| Major Operation (An operation is a sequence of battles and engagements. It is often divided into phases) | Napoleon simultaneously holds off Wellington (Quatre Bras) while defeating Blucher (Ligny) | D-Day (simultaneous landings at five beaches and large-scale airborne landings) |

| Battle (Made up of engagements) | Waterloo | Omaha Beach |

| Engagement | Hougoumont or the French cavalry attack on the Allied line | Point du Hoc |

| Skirmish | Clearing a wood line | Taking out a bunker |

So, what does campaign mean? Well, for our purposes, a campaign is any wargame situation which consists of a group of related operations, battles, engagements, and skirmishes. The results of each influence those following. For example, casualties carry over to the next fight as well as improvements or degradations in morale and perhaps expenditure of fuel and ammo.

Thus, I would not consider a situation in which a group of wargamers simultaneously fought Ligny and Quatre Bras on separate tables to be a campaign. The results of one hardly effected the other. However, fighting the entire Waterloo campaign, from the French crossing into Belgium and proceeding until Brussels was captured or Napoleon turned back is certainly a campaign. But of course, we are talking solo wargaming and therefore whatever you categorize as a campaign will go unchallenged.

Getting Started

So, at this point, the wargamer probably needs to identify just what his campaign will include and what will be left out. This is important because a common mistake is to start with a huge situation that can hardly be concluded in a single lifetime. "I am going to fight World War II in all theaters, including air, ground, and naval operations, down to the battalion and squadron level." My strong advice to the wargamer just starting out is to limit his campaign in three ways: time, space, and goals. Let's take them on one at a time.

Time

Okay, do you want a campaign defined by time? Remember, if you want to fight a campaign to its resolution, you may not want an opened ended proposition. Musket period campaigns are always good in this regard because you can define a campaign as a single campaign season i.e. from when the forage is grown enough to support your horses until the first blast of winter precludes active campaigning. If you haven't reached your goals in the allocated number of turns, you lose. Setting up a campaign from April until November results in 32 weekly turns, for example. You probably want, at this stage, to think about turn length. I favor weekly turns but daily or bi-weekly can work. In modern warfare, in which man and machine can fight through cold or hot weather, perhaps time isn't an important issue. Nonetheless, you may want to identify time periods so that you can use seasonal weather.

Space

A campaign can also be limited by space. My favorite here is fighting over an island. The belligerents can't move all over everywhere trying to avoid a fight and thus prolonging the campaign. The World War II fight over Okinawa, with land, sea, and air combat, describes this situation. Fighting over a single country or land mass accomplishes the same objective, for example, Wellington's campaign, over several years, to clear the Iberian peninsula.

Another way to limit the campaign in terms of space is to tie the armies to the transportation system. I read somewhere that it was virtually impossible to sustain an American Civil War corps more than twenty miles from a rail line or navigable river for more than four or five days unless the surrounding countryside abounded in victuals. Thus you can draw a boundary on your campaign map which recognizes these transportation arteries and forbid your forces to cross those lines in strength.

By combining these concepts, time and space, the wargamer can pretty much limit the campaign to something manageable. For example, in a notional ancient scenario, the Senate has given a Roman commander three years to bring Sicily (ruled by Greeks) into the empire. Which brings us to goals.

Goals

It is very important to identify goals for both sides before beginning. I try to construct levels of goal achievement: marginal, substantial, total, for example. Here's our Sicily example.

- Total Roman victory Sicily entirely subdued, no cities holding out.

Substantial Roman victory Romans occupies 2/3 of cities, remainder under Roman siege.

Marginal Roman victory Romans occupy 1/3 of cities and 1/3 of remainder under siege.

Marginal Greek victory Romans occupy or besiege no more than ½ of cities.

Substantial Greek victory Fewer than 1/3 of cities occupied or under siege

Total Greek victory Romans occupy no cities.

In the above case, either the Roman or Greek can achieve victory, but not both. And, it is possible that neither win any level of victory (a stalemate). You can write the victory conditions to allow both sides to achieve some level of victory. Of course, you can also make the goal all or nothing. For example, Napoleon has until the end of July to occupy Brussels because an Austrian army of overwhelming size will be ready to cross the Rhine in August. This example presupposes that the Austrians will reconsider their role in the coalition if Brussels falls quickly. Failure to occupy Brussels is total Coalition victory and total French defeat.

Okay, now let's put these concepts all together and delineate a campaign.

The Texas Revolution

As my readers will know, I have an abiding interest in the Alamo as a battle and therefore have chosen the Texas Revolution as an example of how one can design a campaign. Time can be limited fairly easily. Santa Anna has no more than one campaign season, January through December, to defeat the rebels. Failure to do so will weaken his support base in Mexico City as well as encourage other provinces to break away from federal control while the main army is tied down in Texas. Fifty-two weekly turns will do nicely.

If you wanted to be complex but perhaps more historically accurate, you could peg the allowable time to Mexican battlefield success. By that I mean, if the Mexican army has not gained control over Texas lands by a pre-determined schedule, then unrest grows in Mexico proper, and Santa Anna has less time to conclude the campaign. Another concept is to increase volunteers from the U.S. as time increases. For example, 100 volunteers each month until May, 150 per month from May through August, and 200 per month between September and December. All these factors encourage Santa Anna to conclude his dirty work as quickly as possible.

Space is limited to the populated areas of the province of Texas. Santa Anna's goals are to gain control over the populated areas. Therefore, game play goes no farther west and north than a line drawn about 150 miles inland of the Gulf of Mexico. The southern limit is the Rio Grande and the eastern limit is the Sabine River, the border with Louisiana.

There are any number of ways to establish campaign goals. After much thought, I decided to divide the playing area into zones between the rivers of Texas according to the chart below.

| A | Land between Rio Grande and the Neuces |

| B | Between the Neuces and the San Antonio |

| C | Between the San Antonio and the Colorado |

| D | Between the Colorado and the Brazos |

| E | Between the Brazos and Rio Trinidad |

| F | Between the Trinidad and the Sabine |

In the goals established below, a zone is occupied when a Mexican force of any size is in each town in the zone and no Texan force greater than 100 men is also in the zone.

| Total Mexican victory | Zones A through F occupied, no Texan forces remaining. |

| Substantial Mexican victory | Zones A through D occupied. |

| Marginal Mexican victory | Zones A through C occupied. |

| Marginal Texan victory | Zones A through C occupied. |

| Substantial Texan victory | Zones A through B occupied. |

| Total Texan victory | No more than zone A occupied. |

Logistics

Leaving our Texas Revolution example for a moment, the wargamer needs to address the level to which he wants to play logistics. I am of two minds. First, logistics isn't fun. Second, without logistics, the game is just that, a game. It is not a simulation; it fails to represent the actual historical event. Thus, I treat logistics as simply as possible, recognizing that logistics imposes a constraint on both sides, limiting what can be done and how fast it can be done. In using a simpler is better approach, I generally just play a few generalized areas of logistics. I play three categories of supplies, food, fuel, and ammo. I also play major pieces of equipment such as replacement tanks, aircraft, and artillery. Finally, I play replacements of soldiers. Now let's look at the Texas scenario and see how logistics might be played.

For food, I decided that I would consider soldiers only, not their mounts. I also assumed that civilians could feed themselves and therefore didn't fall into my calculations. I just based my food requirements on the number of soldiers. I also assumed away a requirement for wagons and teams. I figured that any force could carry food with it without restriction. Yes, this is irrational but it keeps the play simple. Then I defined a unit of food as enough to feed 100 soldiers for 1 week (i.e. One turn). At the end of each turn I just subtracted 1 food unit for every 100 soldiers. I also allocated a food potential for each town. For example, I figured that San Antonio and the surrounding ranchos could generate 20 food units each week.

Thus, whoever occupies San Antonio at the end of a turn adds these food units to his stockage in that town and he can carry it with him when he leaves. Of course, if the occupying force is 2000 soldiers, then all the food is consumed. Now, this means that I have to track food units for each town and for each force and account for consumption (troops) and food generation (towns) each turn.

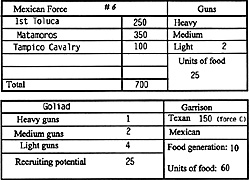

I also played artillery (but not ammunition or gun powder). The Mexicans get a new battery of four medium guns entering Texas every 4 turns and the Texans get two light guns donated by friends in the U.S. every four turns. The Mexican battery crosses the Rio Grande and the Texan guns arrive at Brazoria on the Brazos River.

Mexican replacements arrive on the Rio Grande as battalions (400 soldiers) every 8 turns. Texan replacements come from two sources – volunteers from the United States (already mentioned) and recruited from Texan towns and ranches. The easy solution is just to add a fixed number of recruits to Texan forces each 4 turns but this would not reflect that Texan recruiting would drop as the Mexicans enjoyed success. Thus, I gave every Texan town a recruiting potential and this number joined the nearest Texan garrison every four turns unless the town was occupied by Mexicans.

To keep track of this all, I devised a note card for each force and for each town. Put entries in pencil; they change weekly.

To keep track of this all, I devised a note card for each force and for each town. Put entries in pencil; they change weekly.

Getting Started

Once the campaigner has derived a set of campaign parameters (time, space, and goals) he can start initializing the campaign. This means he allocates forces to starting locations on his map. I like to use a hex map when possible, just for ease of computing move distances. Put the map on a foam core sheet and use push pins to identify the locations of each force. Thus, the opposing sides see only pins on a map, each with a number (Mexican) or letter (Texan) that refers to a note card kept by the appropriate player. Use extra pins which do not have a force associated with them in order to confuse your opponent. Make sure you have a time sheet to cover the turns which reminds all players what happens at the beginning of that turn (e.g. receive replacements).

In our Texas Revolution scenario, Mexicans move first, Texans react. When a force moves into a hex occupied by an opposing force, the opposing force has the option (unless no escape route is open) to fight or flee. He declares his intent. If fleeing, neither side reveals the note card associated with their pin. However, if both sides agree to fight, then out come the note cards and a battle is fought. If a pin turns out to be a phony, it is removed from the game.

Here's a method I use if one side decides to flee after seeing the other guy's force. The fellow who wants to decline battle can do so but pays a penalty of 10% of his soldiers with a fifty soldier minimum. Likewise, if the battle begins and one side decides to withdraw, he pays the penalty in addition to any casualties suffered. This reflects the desertion which often accompanies a lost battle. In group games, a gamemaster is useful in making sure food and replacements are correctly tracked each move.

Playing Solo

It is not that difficult to play the campaign solo. Let's say you want to be the Mexicans and therefore the Texan player is automated. To initialize the game for the Texans, put a pin in each Texan town (I use 12 towns in my game). Then get someone to assist you. Once you have explained the rules, have your helper take the total Texan force and guns and divide them among the 12 towns. You probably want three pins in each town, a small garrison, a force that will move, and a phony force (which will also move). Some light and medium guns can accompany the Texans but most must remain in the towns. Make sure your helper tells you which pins represents the garrisons. Start all forces with enough food to last them four weeks. Thus they must be in a town with food when theirs runs out. If a unit runs out of food, it loses 25% of its men each turn. This reflects a loss of strength to desertion or to troops being sent out to forage. In any event, troops lost never rejoin the unit.

Now, the Mexican (solo) player moves first. In response, he then moves the Texans. The solo gamer can move either or both of the pins in each town representing the Texan moving forces. If moving both pins, the soloist should move the two pins (one real, one phony) in different directions. Of course, not having access to the cards, he doesn't know the size of the forces he is moving. Texan forces should gravitate toward two or three bigger towns. The larger towns generate more food. Also, the Texans should move substantial forces generally toward the Mexicans. They want to defend their territory as well as deprive the Mexicans of food.

Now, the hard part for the soloist is controlling Texan forces close to the Mexican forces. Since the soloist does not know the size of the force he is confronting, he can't make an informed judgement on how the Texan would most probably react (fight or flee). I have devised some fairly simple methods for controlling the Texans and will share them with you in the next column. I will also relate how one of my campaign games unfolded. Until then, you group gamers can consider using solo techniques in setting up group campaigns.

Back to MWAN #100 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com